The True Story Of The American Indian Movement

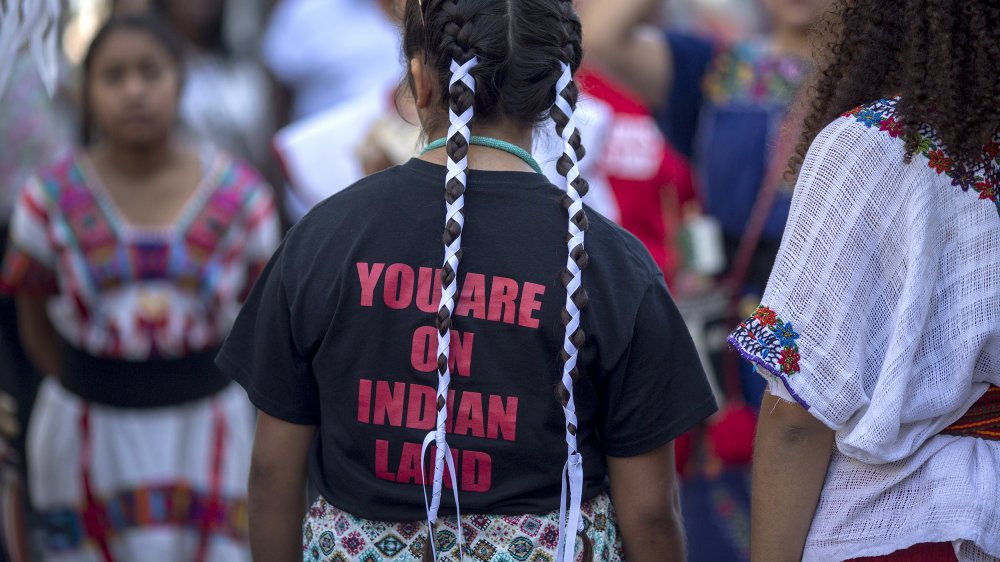

In 1966, Vine Deloria Jr. invoked the notion of Red Power in front of Congress: "Red Power means we want power over our own lives. ... It frightens people I know to talk of Red Power, but we don't want to frighten them. We want to shock them into realizing how powerless the Indians have been." In the wake of the Black Power movement, Native people stimulated their own social movement, putting their demands for self-determination into the public eye.

During the late '60s and early '70s, the American Indian Movement was at the forefront of the fight for Native rights. Organizers spoke out against unemployment, poor housing conditions, and discriminatory treatment, rallying together to found a number of different schools and organizations that advocated for and promoted Native self-determination.

Most well-known for their involvement in occupations, protest marches, and the 1973 standoff at Wounded Knee, the American Indian Movement galvanized a generation of Native youth. And while the movement would split into different factions over the years, their work and advocacy for Native people never wavered.

What was the American Indian Movement?

The American Indian Movement, also known as AIM, was an advocacy group founded in 1968 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. According to the Minnesota History Center, the Native community had suffered under decades of discriminatory federal policies. Reacting to the unlawful arrests and police brutality that their community had been experiencing in Minneapolis, Native people in the area came together to form AIM.

While the movement was initially concerned with addressing specific concerns, such as poverty and police brutality, it soon expanded into a movement that sought to broaden opportunities for Native people all around the United States. A number of Minnesota and national nonprofit organizations were created with the help of AIM, including the Legal Rights Center, the Native American Community Clinic, and the International Indian Treaty Council.

They become a national civil rights group. AIM held a number of protests throughout the years, and their work was instrumental toward furthering Native self-determination in the United States. While both the FBI and the CIA sought to suppress the movement, the spirit of AIM persevered. To this day, the momentum of the original movement lives on, as Native people continue to support and fight for self-determination.

Issues leading up to the creation of the American Indian Movement

In 1953, Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution 108, beginning what was known as the Indian Termination Policy. Tribal termination had already begun in the 1940s. The Kansas Act of 1940 acted as a test run, and within 13 years, it was adopted as federal policy. Termination was aimed not only at getting rid of reservations and treaty obligations but toward forced assimilation of Native people into mainstream (meaning Christian, English-speaking) American society.

Congress passed HCR-108 in order "to end [Native people's] status as wards of the United States, and to grant them all the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizens," seemingly forgetting that Native people were not wards of the state and had already been granted full citizenship in 1924 with the Indian Citizenship Act, and again in 1940 with the Nationality Act.

According to Native Voices, the Supreme Court held up the right of Congress to terminate tribes under the power of the Commerce Clause. From 1945 to 1960, over 100 tribes were terminated, and almost 1.4 million acres of land was lost as its trust status was taken away. This inevitably led to great economic gains for the United States, while decimating Native communities: Under termination, the lands that were taken and sold could now be taxed.

Police brutality in Minneapolis

In May 1968, Dennis Banks was released from prison after having been indicted on burglary charges for stealing groceries for his family. According to him, after having spent his time in prison following the anti-war movement and civil rights struggles, he was determined to start a movement of his own. Immediately after getting out of prison, he called his friend George Mitchell, saying, "I want to get a movement going, and I would like you to help me."

Banks and Mitchell organized the first meeting of what would become the American Indian Movement on July 28, 1968. Almost 200 people attended, and it was at this first gathering that they would meet Mary Jane Wilson, Vernon Bellecourt, and Clyde Bellecourt, who would become instrumental in the movement.

It was during this first meeting that Clyde Bellecourt spoke out about the issue of police brutality that the community faced. They banded together that night to go to an area of high police activity to act as a patrol: AIM was born. Initially, Mitchell had wanted to call the group the "Concerned Indian Americans," but once they realized that the initials spelled "CIA," they came up with the American Indian Movement. They formed the AIM Patrol, who, through observation and deescalation, were able to lower rates of not only police abuse of power but also intra-community violence. While the patrol didn't interfere with police work, their presence acted as a deterrent against abuses of power.

The growth of the American Indian Movement

Within two years, the American Indian Movement had grown to over 5,000 members, according to Dennis Banks, and within five years, AIM had 79 chapters around North America. Over the next few years, the movement worked to create numerous organizations to assist Native people. As AIM Patrol documented instances of police brutality and led to a drop in arrest rates, they also started a radio program on KUXL to broadcast issues of Native importance.

One of the organizations that AIM helped found is the Legal Rights Center. They assist Native people with legal issues and continue to operate and provide legal aid to this day. AIM also helped open the Indian Health Board health clinic, which also continues to promote health care for Native people.

Another primary concern for AIM was the education of Native youth, and they challenged the Minnesota public school system to enact a more diverse curriculum. When their demands were ignored, AIM went on to create their own schools for Native youth. Native youths themselves were the ones advocating for an alternative education. The schools were established not only to provide a more inclusive curriculum but to also address the almost 50-percent dropout rate of Native students within the public school system.

Occupying to raise awareness

The American Indian Movement is most well-known for its various occupations, and while the most famous occupation they assisted with is the occupation of Alcatraz, they were involved in many throughout the years. In September 1970, AIM helped Lizzy Fast Horse and Muriel Waukazoo occupy the Six Grandfathers, also known as Mount Rushmore. They would remain camped there for almost four weeks, unfurling a flag that read "Sioux Indian Power" on the sacred Black Hills. Later that year, they would also occupy a replica of the Mayflower on Thanksgiving to bring attention to the mistreatment perpetrated by the first colonizers.

In May 1971, AIM activists organized a seizure of the Twin Cities Naval Air Station, a facility that was soon to be closed, demanding that the government give the area over to Native people so that they could develop an educational and cultural institute. This was part of a wider effort to reclaim land that the United States had abandoned, and though the activists were removed after four days, their efforts were essential in increasing public awareness.

According to Indian Country Today, AIM activists would try to reclaim the Six Grandfathers again in 1971. Scaling the mountain once again, they demanded that the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty be honored. This time, the protesters were forcibly removed after 12 hours, and 20 people were charged with trespassing, although the charges were eventually dropped.

The Trail of Broken Treaties

In 1972, the American Indian Movement, along with the National Indian Brotherhood of Canada, the National Indian Youth Council, the Native American Rights Fund, and the American Indian Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse, organized a nonviolent protest that involved a caravan traveling from the West Coast to Washington, DC. According to the Global Nonviolent Action Database, the caravan was to commemorate the Trail of Tears and the Long Walk of 1864, as well as the relocation and displacement that had occurred as a result of termination policies.

Beginning on the West Coast in October, three caravans departed from Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles and began to make their way across the country. They planned to arrive during the last week of the 1972 presidential election. The caravans passed through reservations as they traveled east toward the nation's capital, holding workshops and gathering supporters for their movement. By the time protesters converged on the capital, there were almost 1,000 people from tribes from all across North America.

Halfway through their trek, in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Hank Adams wrote the Twenty Point Position Paper, a proposal that they intended to present to President Nixon at the end of their journey.

The 20-point proposal of the Trail of Broken Treaties

As part of their Trail of Broken Treaties, the American Indian Movement made a list of 20 points that they wished to present to the federal government. According to Intercontinental Cry, while some Native leaders considered the points to be too militant, most tribal leaders thought of them as a chance to support the rights and improve the lives of Native people.

From the get-go, the Twenty Point Position Paper sought to return Native sovereignty to the people. In their first point, they demanded the repeal of the provision in the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act which had ended federal recognition of Native nations and tribes and destroyed the diplomacy of treaty-making that had existed for 100 years. From there, there was to be a new treaty commission that included Native people, as well as a committee to determine treaty violations.

While most of the points ranged from the restoration of terminated rights to providing relief to Native people as compensation for the various treaty violations over the years, the final point touched on health, which was seen to be of critical importance. There was a staggering lack of sewers and pure water sources on Native reservations, resulting effectively in another genocide of Native people. Writing in the final point, Adams stated, "Death remains a standard cure for environmentally induced diseases afflicting many Indian children without adequate housing facilities, heating systems, and pure water sources."

Occupation of BIA headquarters

Once the Trail of Broken Treaties protest caravan arrived at Washington, DC, the few plans that they had fell through. Though local churches had offered to shelter and feed the protesters, once the almost 1,000 people got to DC, the offers were withdrawn, leaving the protesters stranded. In addition, the Nixon administration refused to meet with the protesters to discuss the 20-point proposal.

According to Washington Area Spark, leaders of the march were in the process of negotiating some sort of temporary housing with the Interior Department when security guards started trying to force people out of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The guards hadn't realized that the protesters had permission to stay past the building's closing, and as a result of the scuffle, the guards themselves were removed from the building and the protesters occupied the BIA.

The occupation lasted several days, and while the Nixon administration had agreed not to prosecute the occupiers and to create a task force to address the grievances of Native people, they ended up reneging on many promises. Although Nixon did restore some tribal rights and appoint a Native person to a post at the BIA, many of the points in the original 20-point proposal remain to be addressed today. The greatest victory for the protesters was their removal of documents from the BIA in order to make copies and expose the corruption that had permeated Washington's relationship with Native people.

Occupation of Wounded Knee

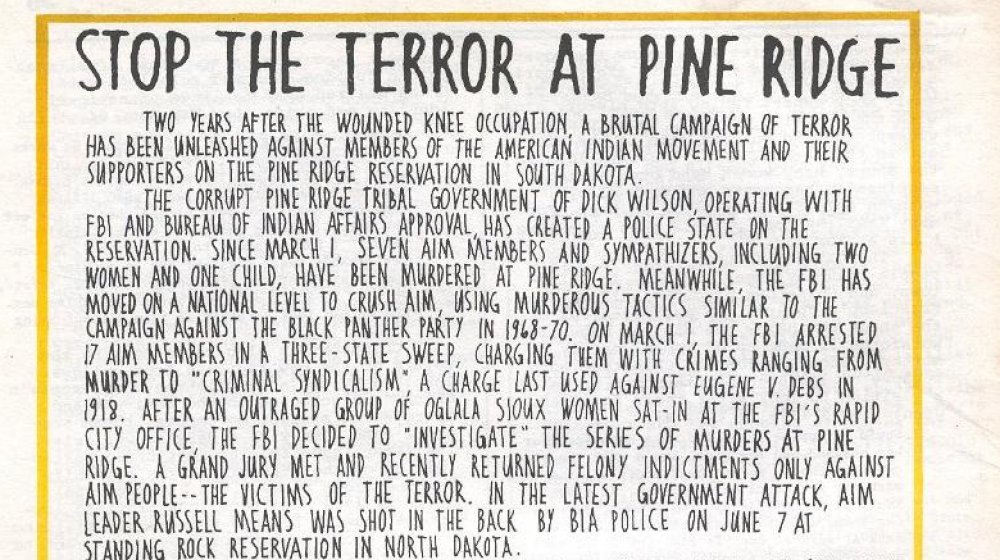

In 1973, the American Indian Movement occupied the town of Wounded Knee for 71 days. According to Indian Country Today, the occupation began after elders of the Oglala Sioux tribe reached out to AIM asking for help in dealing with corruption in their government. Chairman Dick Wilson, a tribal official they were unable to impeach, anticipated the protest and got the FBI and US Marshals to back him. Almost 200 Oglala and AIM activists would end up occupying Wounded Knee, receiving widespread support, from the Congressional Black Caucus to actor Marlon Brando.

There were many bouts of gunfire, from both federal agents and AIM protesters, but negotiations carried on throughout. Protesters demanded a probe into corruption on the reservation and action against issues such as poverty. According to The Atlantic, after Buddy Lamont was killed by a government sniper on April 26, tribal leaders decided to end the occupation as quickly as possible. After surrendering on May 8, many AIM activists were arrested, although they would end up being acquitted after key evidence was mishandled.

While the occupation helped keep Native issues in the limelight, it wasn't a success. White House officials made an empty promise to investigate the claims of corruption, and Wilson was able to remain in power. Within several years, Pine Ridge reservation's per capita murder rate was the highest in the country, and a number of activists from the occupation, such as Anna Mae Aquash, were killed under suspicious circumstances.

The Longest Walk

The American Indian Movement would continue to use protest marches to draw attention to their causes. On February 11, 1978, AIM began what would became the first of their "Longest Walks." According to the National Museum of the American Indian, the 3,000-mile march was held to protest 11 anti-Native bills as well as to continue to bring attention to the rights of Native people. Symbolizing the forced removal of Native people from their homelands, the walk drew attention to the continuous threats to treaty rights experienced by Native people.

After gathering on Alcatraz Island, which had been under Native occupation less than ten years prior, the group of protesters began their walk across the United States. The walk took five months, and by the time activists and allies arrived on July 15, 1978, there were almost 2,000 people walking into Washington, DC. At the end of the walk, activists and marchers united for a concert, with figures such as Muhammad Ali, Stevie Wonder, and Marlon Brando joining in to show their support.

History appeared to be repeating itself when President Carter refused a meeting with the marchers, but public pressure thanks to the protesters would cause Congress to veto all 11 of the anti-Native bills. In addition, Congress would pass the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which, for the first time in history, gave Native people the right to practice their own religion.

The Longest Walk II

In 2008, more than 800 people gathered together to repeat The Longest Walk. As with the first walk, the protest took five months as people walked from San Francisco to Washington, DC. According to Dennis Banks, The Longest Walk II was to bring awareness to environmental issues as well as sacred sites. Having noticed the effects of global warming on reservations, they decided to make environmental issues the centerpiece of the walk, while still raising a variety of critical issues as well.

Protection of sacred sites had been demanded 30 years before during the first walk, and while places like the Liberty Bell and Arlington National Cemetery receive protections, there continue to be no equal protections for Native peoples' sacred sites. Another issue noted by Banks was the return of artifacts and bones that continue to be kept in universities rather than being allowed a proper burial.

This time, when The Longest Walk II reached Washington, DC, they wouldn't be ignored by the government. According to PBS, when The Longest Walk II arrived on July 11, 2008, Congressman John Conyers accepted their 30-page manifesto, stating, "It has demonstrated to us in the Congress that climate change, social injustice, and a broken health care system are challenges that demand real solutions in the here and now."

The American Indian Movement today

In 1993, the American Indian Movement would split into the AIM Grand Governing Council and the AIM International Confederation of Autonomous Chapters. At the time, the FBI was allegedly killing and imprisoning various members and leaders, and there were also disagreements among AIM activists about the methods being used in their activism. According to Reuters, the break ultimately occurred due to infighting and accusations of betrayal, but despite the schism, both organizations continued with their activism.

There would be several more Longest Walks. In 2011, Longest Walk III focused on health care and the diabetes epidemic. In 2013, Longest Walk IV focused on Native sovereignty, walking the route backward from Washington, DC, to Alcatraz. And in 2016, Longest Walk V focused on domestic violence and drug abuse.

Many of those who were active in the early days of AIM went on to create movements of their own. One example is Women of All Red Nations (WARN), which concerns itself primarily with the issues facing Native women. Many of the Native women who founded WARN had been active in AIM but wanted to emphasize the role that gender played in the Native experience, especially under the effects of colonization. AIM Patrol has also been revitalized in Minneapolis, coming together to provide protection to the community in the aftermath of George Floyd's murder.