False Things You Believe About The Constitution

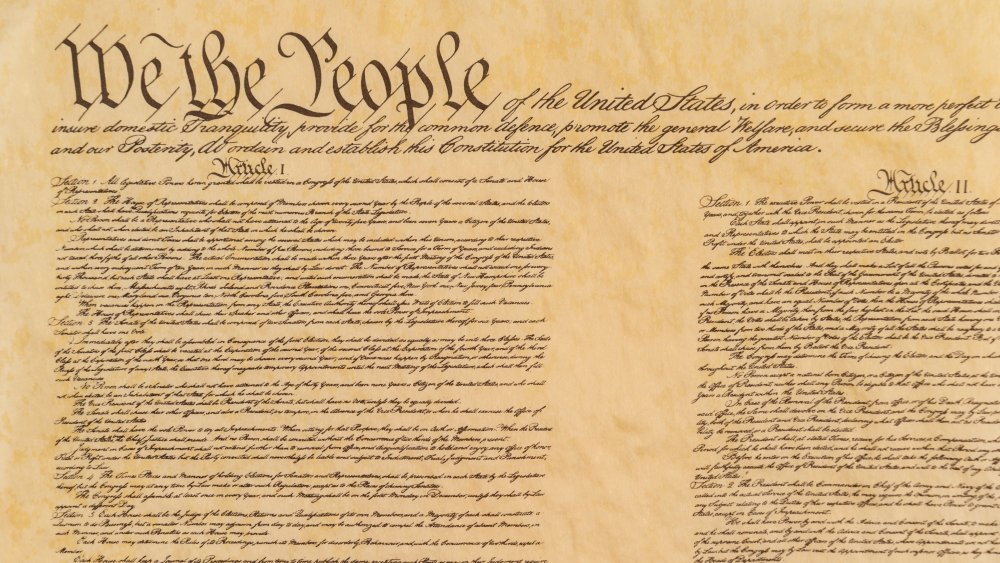

The Constitution of the United States is the most important document in our country. It not only defines the structure of our government, but it also outlines the fundamental rights we enjoy as citizens. The United States Constitution is the oldest constitution still in force in the world, and it's easy to forget just how unique and innovative it was more than 230 years ago when it was first composed. There's a reason, after all, that our country and our system of government used to be referred to as "The American Experiment."

It's not a difficult read: The entire document, including the first ten amendments commonly referred to as the Bill of Rights, is less than 10,000 words long. English spelling wasn't standardized in 1788, and the writing style seems a bit stiff and complex to casual readers today, but it's still pretty straightforward. So it's surprising how many myths and outright falsehoods surround our foundational document, and how many Americans know very little about it. Whatever your level of constitutional knowledge, some of the false things you believe about the Constitution are probably on this list.

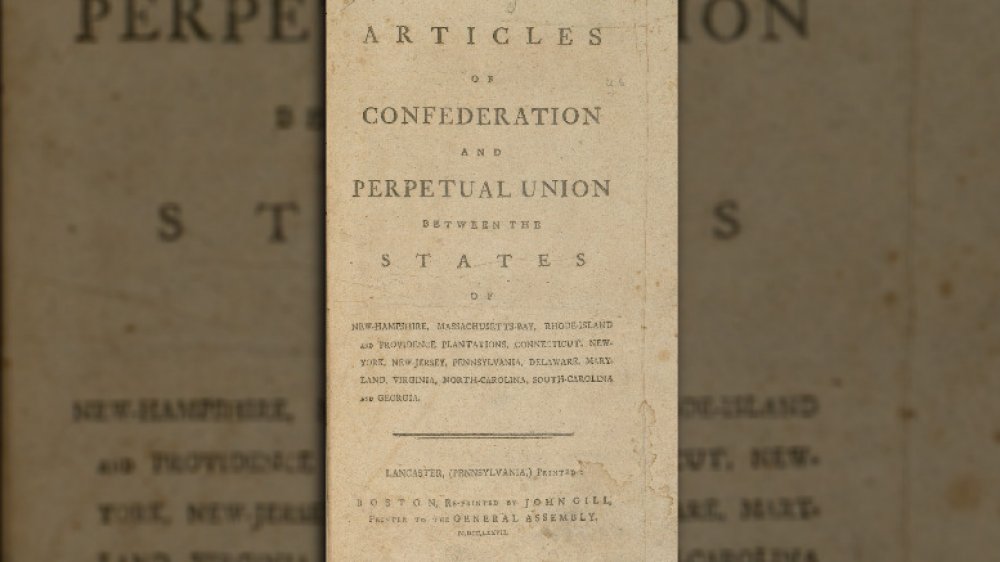

Myth: the Constitution was America's first government

A surprising number of people think that America emerged from the Revolutionary War with the Constitution in hand and held the first presidential election right away. But as the Library of Congress details, the Founding Fathers actually went through a lengthy process of figuring out what, exactly, our government should look like. This started with a framing document authored by Benjamin Franklin, which eventually evolved into the Articles of Confederation. The government described by the Articles was very different than what we have today. The central government was extremely weak, which makes sense for a bunch of revolutionaries who'd just fought a lengthy and expensive war for their freedom. The Articles were ratified in 1781, and America was governed under those rules until 1789.

Under the Articles of Confederation, there was no executive branch at all — and no president of the United States. As ConstitutionFacts notes, there was a president of the Confederation Congress, John Hanson, but it was a largely ceremonial role. Hanson had very little power or influence and can't be considered a "president" in the same sense as George Washington.

Ultimately, the Articles of Confederation quickly proved to be unworkable, and the need for a strong federal government and a chief executive with real power quickly became obvious — leading to the drafting and ratification of the Constitution. But despite being a marked and obvious improvement, the Constitution is actually the second governing document of our country, because we got it wrong on the first try.

Myth: the First Amendment is first for a reason

Even folks who don't know much about the Constitution know at least some of the rights spelled out in the Bill of Rights — like the First Amendment, the right to free speech. And plenty of people think that its placement at the very top of the list is meaningful – because the right to free speech is so fundamentally important, and all the other rights flow from it.

That's a nice idea ... but it's totally untrue. The Bill of Rights came about because plenty of people involved in creating the Constitution noticed that it doesn't actually spell out very many specific rights. Having fought a costly war for their individual freedoms — and very suspicious and fearful of a strong federal government that might evolve into another tyranny — a lot of representatives demanded that certain things be guaranteed, and a list of amendments was drawn up. As The Washington Post writes, the first two on the list were concerned with the number of representatives in the House of Representatives and their salary and were rejected.

The amendment about not limiting free speech moved up to the first spot as a result — completely by chance — which doesn't mean the Founders didn't think it was important. It just means that sometimes, we imbue meaning into things when there's actually none there.

Myth: the Constitution states all men are equal and guarantees a democracy

The phrase "all men are created equal" is certainly inspiring, but if you think it comes from the Constitution, think again — the phrase actually appears in the Declaration of Independence, which isn't a legal document with the force of law. In fact, the Constitution literally says the exact opposite.

As ThoughtCo. notes, the Framers of the Constitution had to navigate the problem of slavery. In what would set a pattern for the ensuing 80 years, instead of just getting rid of it, they made a bad compromise to placate the slave-holding states: the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted slaves (without actually using the term) as three-fifths of a person for the purposes of representation and taxes. The idea was to prevent the Southern states from gaining too many extra representatives because of their non-voting, non-free slaves. But as a result, the Constitution goes completely against the concept of all men being created equal.

It also doesn't actually describe or promise a democracy. A democracy is a system whereby every member of a society votes directly on every issue. What the Constitution describes is a republic, wherein a group of people are empowered to vote on everyone else's behalf. As The Washington Post points out, this could be described as representative democracy, but the Constitution makes the distinction clear in Article Four: "The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government."

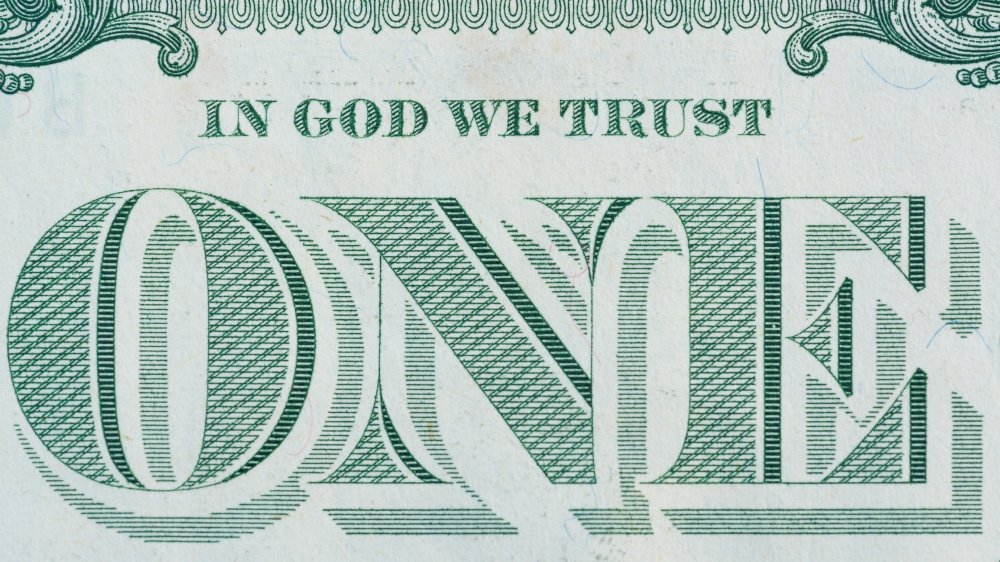

Myth: the Constitution contains the word "God"

While Americans hold the concept of the separation of church and state dear, many people assume that the United States was founded as an explicitly religious nation. After all, that's why we have "In God We Trust" on our currency and why the Constitution makes so many references to God.

Except, as Politico reports, the phrase "In God We Trust" was added to our currency in 1956, when President Eisenhower signed a law making the phrase our national motto. And the Constitution actually never mentions God once — instead, it explicitly states that power flows from "the people," not a deity.

This wasn't an oversight. As The Atlantic writes, the Founding Fathers and Framers of our Constitution were deeply skeptical of organized religion. In fact, in 1797, President John Adams signed a treaty with Tripoli that explicitly states "the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion." Many monarchies claimed that power was bestowed on the king or queen by "divine right," the idea that God had chosen them and their descendants to rule. Having just freed themselves from a monarch who believed fervently in that concept, it's little surprise that they wanted to clearly reject the idea.

Myth: the speaker and the president pro tempore have to be members of Congress

Most Americans know the House of Representatives elects a speaker to be in charge of things like committee assignments and scheduling votes. Less well-known is the Senate's president pro tempore, who acts as president of the Senate when the vice president isn't around. Why is the vice president also president of the Senate? Because as delegate Roger Sherman of Connecticut put it, "if the vice-President were not to be President of the Senate, he would be without employment."

Every speaker of the House has been a member of congress, and every president pro tempore of the Senate has been a senator, so it's easy to see why a lot of people assume that the Constitution makes this a rule. But it doesn't. As the National Archives notes, the Constitution simply states that the "House shall chuse their speaker" and "The Senate shall chuse ... a President pro tempore." (And yes, that's how they spelled "choose.") In other words, it's only tradition that makes Congress choose elected members for these roles.

This is fascinating when you remember that the speaker of the House is third in line in the presidential succession, and the Senate's president pro tempore is fourth, meaning that it's entirely possible that someday, someone who has never won an election could potentially become president of the United States.

Myth: the president can veto an amendment

For a country that was founded because our forebears couldn't tolerate the unchecked authority of their government, there are a lot of crazy ideas about just how powerful our president is.

As The Atlantic reports, the Constitution is actually kind of vague and skimpy on precisely what the president is able to do. Over the years, the accepted authority of the office has changed, and some modern theories have emerged that try to retroactively make the president a much more powerful figure than the Constitution actually describes. Known as the Unitary Executive Theory, the general idea is that the president has complete and total authority over the Executive Branch of the government, and it's done a lot to promote the idea that the president can do a lot of things they really can't — like veto an amendment to the Constitution.

It's an understandable assumption. The president can veto laws, after all, so it seems to follow that they can veto amendments. But it's wrong. As Reader's Digest explains, the president actually has exactly nothing to do with amendments — they can't propose one, vote on one, or veto one. If congress passes an amendment and 38 states ratify it, it's law, and there's nothing in the Constitution giving the president any say about it.

Myth: the Constitution outlines every aspect of our government

A lot of people think the Constitution is a blueprint for our government, outlining every aspect of the Legislative, Judicial, and Executive Branches. Considering that the Constitution itself, not counting the Bill of Rights, is less than 5,000 words long, that's kind of impossible.

The fact is, as Professor Wendy N. Whitman Cobb, Ph.D., points out, many aspects of the Constitution were left intentionally vague — and many things were simply not addressed at all. This was a conscious decision on the part of the Framers. Being a short, broad document is the reason our Constitution, a document written in the late 1780s, remains functional. If the Constitution were more specific and more detailed in precisely how the government should work, it would have become obsolete long ago.

On the other hand, as FiveThirtyEight makes clear, that also leaves plenty of room for argument and varying interpretations — which, in turn, lead to Constitutional crises. A Constitutional crisis occurs when no one can agree on what happens during an unexpected event. For example, until the 25th Amendment was ratified in 1967, if the president died in office, there was no official rule that stated the vice president actually became president as opposed to simply acting president. So every time a president died in office before 1967, it was a gray area that had to be argued over.

Myth: the states unanimously embraced the Constitution

The way people talk affectionately about the Constitution these days, you might imagine that it was universally adored when first introduced and was quickly and unanimously ratified. The truth is quite the opposite — many states, worried about losing the independence they'd recently won, took some convincing.

If you've seen the Broadway play Hamilton, you've heard of the Federalist Papers. As History reminds us, these essays were written anonymously by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison to convince the states that the country needed a strong federal government and to ratify the Constitution. It took almost a year for nine of the states to approve the Constitution, thus making it the official law of the land.

Some states still dragged their feet, but by 1790, 12 of the 13 states had officially ratified the Constitution. The one holdout was Rhode Island, which hadn't sent any representatives to the Constitutional Convention, either. (The National Archives notes that for years, the state's unofficial nickname was "Rogue Island.") As Politico reports, it was only when its neighbors threatened to begin treating it as a foreign nation and start taxing its exports that Rhode Island gave in — and even then, it took the state 11 failed tries before it finally succeeded.

Myth: the Constitution forbade women from voting

It's common knowledge that women couldn't vote prior to 1920, when the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified. That leads a lot of people to assume that the Constitution explicitly states that women can't vote, hence the need for an amendment. But that's not actually true. As the National Park Service notes on their website, the 19th Amendment wasn't needed because the Constitution explicitly took the vote from women but because it was completely silent on the matter. The Constitution doesn't actually state that women can't vote — it simply doesn't state that they can. The fact that our sexist forebears decided that women couldn't vote had nothing to do with the Constitution.

In fact, it was perfectly legal for women to vote prior to 1920 — if an individual state allowed it. In New Jersey, for example, women and Black people were specifically permitted to vote prior to 1807. The state had some weird restrictions (married women couldn't vote, but single women could), but the law was very specific, using the phrase "he or she" to make it crystal clear. The law was changed in order to give the Democratic-Republican Party an advantage in the elections, which sounds about right for Jersey politics.

And as The Salt Lake Tribune reports, an equal suffrage law was passed in Utah in 1870, and a woman named Seraph Young voted in a municipal election that year. About 25 other women voted in that election as well.

Myth: the Bill of Rights immediately applied to every state

The Bill of Rights isn't a bill at all, actually — it's a collection of amendments to the Constitution. These amendments were introduced to assuage the concerns of some delegates to the Constitutional Convention that the government created by the Constitution would be too powerful. Today, those amendments are iconic aspects of what it means to be an American, and people who don't know much about how our government works can still name at least some of them.

They also probably think those amendments were in force throughout the United States from their ratification, but as the Chicago Tribune explains, that's not true. Until well into the 20th century, the Bill of Rights only applied to the federal government. In other words, the First Amendment prevented the federal government from passing any laws inhibiting freedom of speech — but it didn't stop the states from passing all the laws they wanted doing just that.

In fact, as Britannica notes, it wasn't until 1925 that the US Supreme Court made it official that the First Amendment applied to state governments as well. Freedom of religion wasn't extended to state laws until 1947, and it wasn't until 1968 that the right to a jury trial was finally applied to state governments.

Myth: income tax is in the Constitution

They say the only sure things in life are death and taxes, but if you think the Constitution includes provisions for income taxes, you weren't paying attention in school when they explained the Revolutionary War.

Although income tax seems like a permanent part of life these days, as the National Constitution Center explains, the Constitution actually severely limited the taxes that the federal government could levy. This isn't surprising for a country that used the rallying cry "No taxation without representation!" during its rebellion. But that caused the country a bit of difficulty when it came to paying its bills. As the US grew larger and more modern, the traditional revenues received from indirect taxes like tariffs just weren't enough. There had been income taxes (most notably during the Civil War), but they had always been temporary and controversial direct taxes that were repealed as quickly as possible.

The push to create an income tax gathered steam in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was pitched initially as largely a tax on the very rich, and even so, it met a lot of resistance. It also required an amendment to the Constitution to be legal, something that President William Howard Taft managed to achieve in 1913.

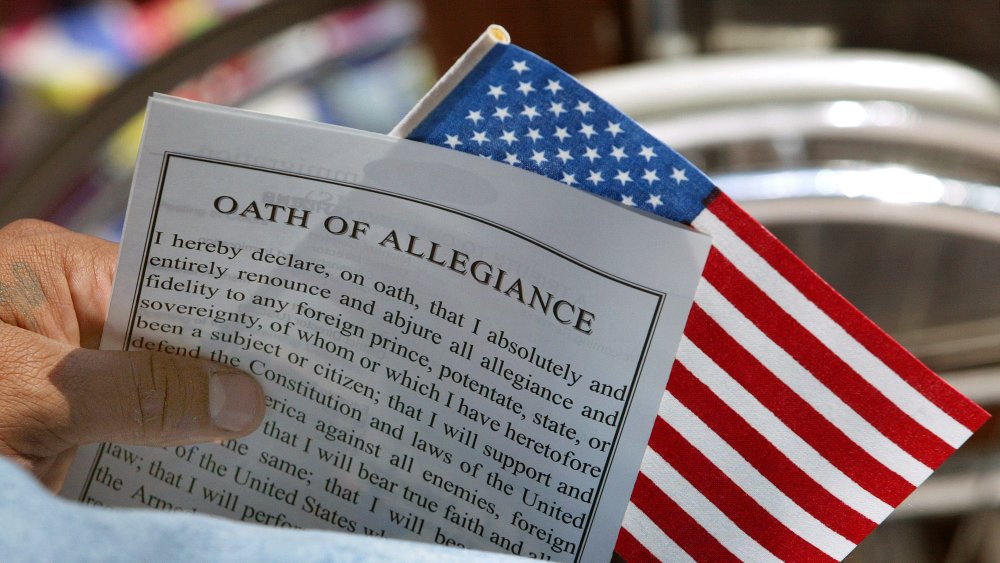

Myth: you have to be a citizen for the Constitution to apply

Being a citizen of the United States is a big deal — such a big deal that hundreds of thousands of people try to gain that status every year. Citizenship comes with a lot of benefits, but if you think you have to be a citizen for the legal rights and protections outlined in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights to apply to you, you're 100-percent wrong.

As the Project on Government Oversight notes, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights use the word "citizen" very rarely, and usually only in the context of the right to vote. In every other instance, the word used is "person." What this means is that once you're living inside the borders of the United States, you have all the legal rights and protections granted by the Constitution and those first ten amendments. You don't have to be a citizen.

As the Chicago Sun-Times notes, that's why the Census, for example, has never asked people about their citizenship status. The use of the word "persons" in the Constitution stems from the Three-Fifths Compromise that counted every slave as three-fifths of a "person" for purposes of representation and taxation — since the slaves weren't citizens, the Framers had to avoid using that word.