The Most Important Racial Court Cases In U.S. History

Throughout the history of the United States, court cases were often the places where major civil rights battles were fought. If something couldn't be decided upon at the state level, the case would go up all the way to the Supreme Court. While a handful of racial court cases, such as Dred Scott and Brown, are taught in school, there are countless others in US history that brought the fight for racial equality to the federal stage.

Many of the rights and freedoms that people enjoy today came about as a direct result of people challenging injustice. But not every challenge against injustice ended in victory, for many court cases led to precedents that would take decades to undo. Even today, some have yet to be completely overturned. But the litigious nature of the United States persists, and people continue to fight for their equality. These are the most important racial court cases in US history.

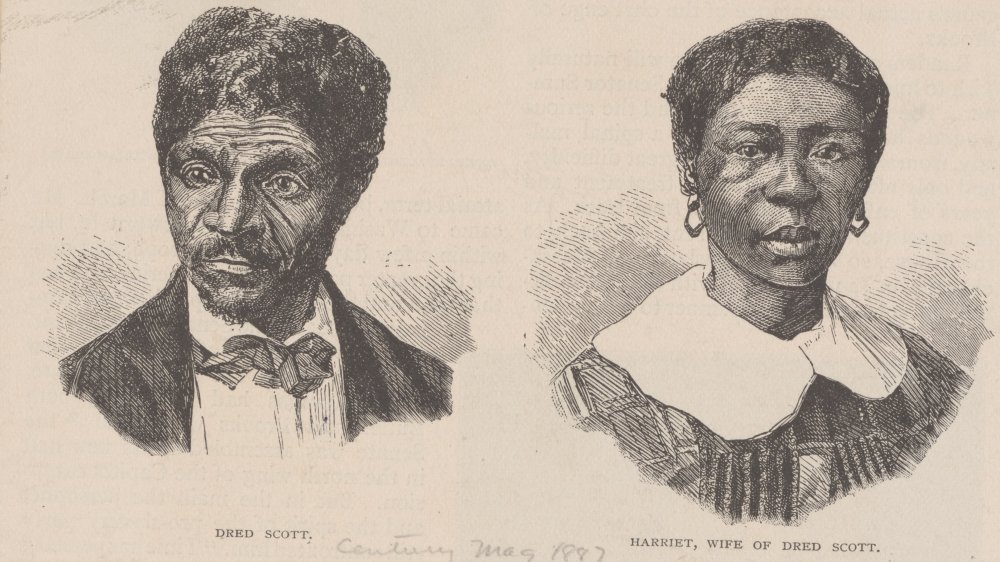

Suing for freedom

Freedom suits have historically allowed people who were enslaved to argue their right to freedom in a legal setting. According to William G. Thomas III, a professor of history at the university of Nebraska-Lincoln, "Slavery was challenged in court by enslaved people almost from Day 1 of the United States in 1789." In Rachel v. Walker for example, the Missouri Supreme Court determined that if a US Army officer takes an enslaved person into a territory where slavery is illegal, then their enslavement is nullified.

In 1846, Dred Scott attempted to use this precedent to sue for his family's freedom. Scott and his family had been taken into Wisconsin territory by their enslaver Dr. John Emerson, an Army doctor, and since slavery was illegal there, Emerson had effectively forfeited his claim over Scott. According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Scott lost his initial case, and after various appeals, the case ended up at the US Supreme Court.

In 1857, the Supreme Court would rule in Dred Scott v. Sandford that since Black people were not American citizens, they had no right to file a claim in federal court, effectively putting an end to freedom suits. The Supreme Court would also rule that Congress had no constitutional right to outlaw slavery. This ruling would later be overturned by the 13th and 14th Amendments, but the Dred Scott ruling has been called by many "a stain" on the country's history.

Civil rights, take one

While it took until 1964 for civil rights legislation to stick, the first time the United States passed civil rights laws actually occurred almost 100 years earlier. According to ThoughtCo., Congress passed a number of laws after the Civil War that were meant to ensure racial equality. The most expansive of these was the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which criminalized racial discrimination in private businesses, modes of transportation, and public places.

Despite this law, many establishments, especially in the South, had already begun setting up segregated spaces. As a result, Black people still experienced a great deal of discrimination, and there were multiple instances of prosecutions as they continued to experience discrimination and segregation. Five cases, United States v. Stanley, United States v. Ryan, United States v. Nichols, United States v. Singleton, and Robinson v. Memphis & Charleston Railroad, would go all the way up to the Supreme Court.

It was in 1883 when the Supreme Court dealt a near-fatal blow to civil rights, giving their decision to all five cases in one surprise ruling. In an 8-1 decision known as the Civil Rights Cases (1883), the Supreme Court decided that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional, since neither the 13th nor the 14th Amendment gave Congress power over the actions of private individuals and businesses. This ruling effectively limited the federal government's ability to guarantee civil freedom, leading many states to ratify racial segregation into law.

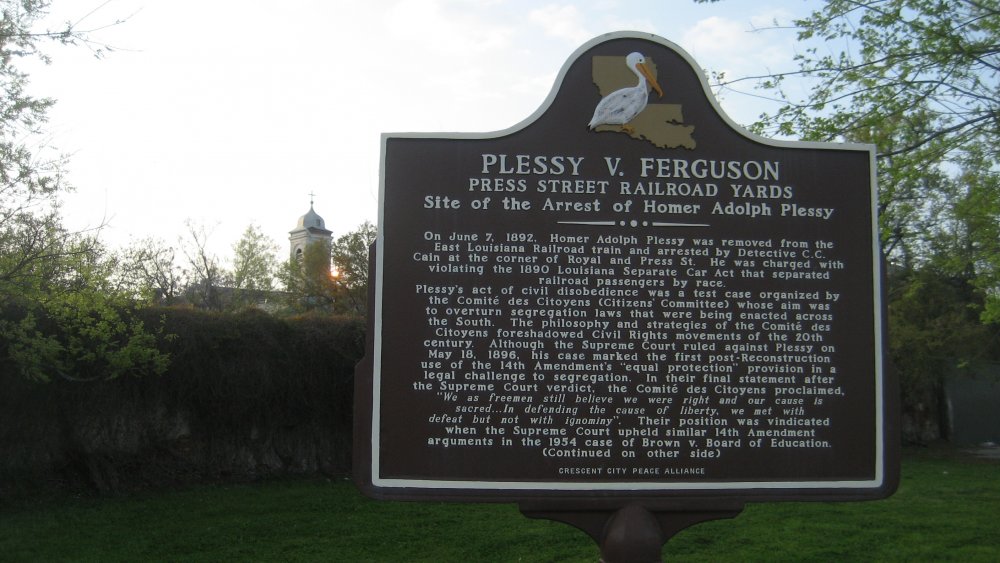

When they said separate was equal

After the Civil Rights Act was struck down, segregated spaces popped up all over the United States, upheld by legislation that stipulated "equal but separate accommodations." In 1892, one of these laws was challenged by Homer Plessy after he was convicted for traveling in a whites-only train car in Louisiana.

According to PBS, Homer Plessy was seven-eighths white and one-eighth Black and was considered white-passing. And while Plessy would've normally ridden in the whites-only car without any issue, his arrest in 1892 was part of an orchestrated plot that planned to challenge the segregation laws in court. Plessy was working with the Citizens' Committee, and in order to ensure his arrest under the separate car law, the committee had not only called ahead to notify the railroad company of Plessy's intent, but they'd hired their own private detective to make sure the arrest went exactly as planned.

In Plessy v. Ferguson, Plessy's lawyer Albion Tourgée argued that the Louisiana law violated the 14th Amendment right of equal protections under the law. Unfortunately, the plan would backfire, as the Supreme Court ruled 7-1 that segregation was not unconstitutional, since the equality guaranteed by the 14th Amendment applied to political rights rather than social rights. The court would also rule that a distinction of "separate but equal" was necessary if white people were to continue distinguishing themselves from other races and thus had no negative bearing on legal equality.

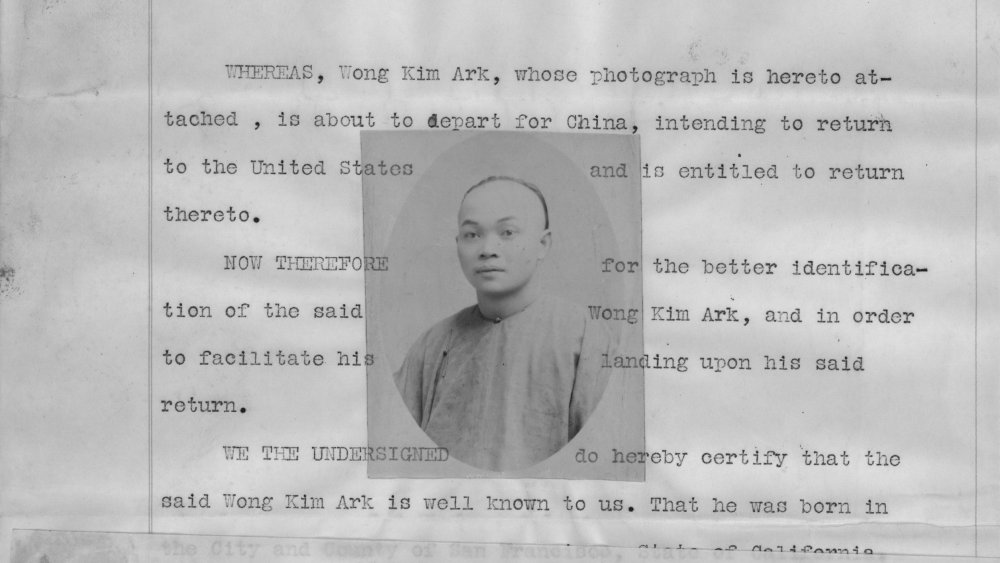

Where birthright citizenship comes from

While the 14th Amendment technically guaranteed citizenship to anyone born in the United States from its inception, it remained up to interpretation until the 1898 court case United States v. Wong Kim Ark. Nine years before the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, Wong Kim Ark was born to Chinese parents in 1873 in San Francisco. Wong's parents returned to China, and after one of his visits in 1895, Wong was refused entry into the United States, with the customs officer claiming that he was not a US citizen and deportable under the Chinese Exclusion Act.

According to Politico, Wong challenged his deportation ruling with the help of a Chinese immigrant aid society, taking the case to federal court. It was in this case that the Supreme Court solidified the notion of citizenship as conferred by the 14th Amendment, deciding that no matter the citizenship of the parents, anyone born on United States soil is a citizen.

Considering that this was the same court that upheld segregation only a few years prior, it's safe to say that the justices did not mean to put aside their racist ideologies. Rather, they knew that if they didn't interpret the 14th Amendment in this way, they'd end up denying "citizenship to thousands of persons of English, Scotch, Irish, German or other European parentage who have always been considered and treated as citizens of the United States."

What does it mean to be white?

In 1914, Takao Ozawa applied for citizenship after having immigrated from Japan to California in the mid-1890s before settling down in Hawaii. According to PBS, Ozawa argued that he was fluent in English, that his skin was just as white, if not whiter, than a white man's, and that he was a true American at heart.

After Ozawa's petition for naturalization was rejected, he would appeal repeatedly until the case reached the Supreme Court in 1917 with Ozawa v. United States, arguing that he was eligible for naturalization since the original 1790 naturalization laws only excluded Black and Native people. However, the Supreme Court would determine that the intention of the original provision "is not that Negroes and Indians shall be excluded but it is, in effect, that only free white persons shall be included," as Justice Sutherland would say.

Justice Sutherland also went on to say that while the court did not argue the fact that Ozawa was a highly qualified candidate for citizenship, the issue was whether or not he could be considered a "free white person." And the consensus of the court was that "the words 'white person' were meant to indicate a person of what is popularly known as the Caucasian race."

What does it mean to be white? (part two)

While the United States had been tentatively granting citizenship to Indians at the beginning of the 20th century, such as Bhicaji Balsara and Sakharam Ganesh Pandit, this practice came to an end in 1923. Bhagat Singh Thind was first granted citizenship in 1918, when he joined the US Army, but his status was abruptly cancelled by the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Thind then applied for citizenship in 1919, only to have his acceptance appealed once more by the INS.

According to the AAREG, Thind took the case to the Supreme Court with United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind and argued that since Indians were considered part of the Aryan race, then they would fall under the qualifier of Caucasian as established by Ozawa. However, the court ended up contradicting their ruling in Ozawa, as they came to the conclusion that despite their designation of "Caucasian" as the benchmark, they did not mean "Caucasian" in a scientific or anthropological sense.

Whiteness was to be understood in terms of "common understanding," meaning those who explicitly looked white. It was this logic that allowed Armenians and Syrians to become naturalized citizens while denying other people of various Asiatic descent. This standard of whiteness in exchange for citizenship remained in place until the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, which got rid of race and national origin as criteria for citizenship.

Is segregation black and white?

In 1924, Martha Lum was nine years old when she was denied the ability to attend school because of her Chinese heritage. Her family lived in Mississippi, which had segregated schools at the time, and according to the Zinn Education Project, Chinese parents would rarely send their children to the "colored" school. More often, they would send their children to a white school until someone would dismiss them for being "colored."

Lum had attended a white school for a year, and when her parents, Jeu Gong and Katherine, tried to re-enroll her the following fall, they were told that she couldn't attend due to her ineligibility as a Chinese girl. Her parents sued in an effort to end Chinese segregation from white schools. They won their first appeal, but the Mississippi Supreme Court reversed the decision, leading them to take their case to the Supreme Court with Gong Lum v. Rice.

The Supreme Court would affirm the reversal of the Mississippi Supreme Court, stating that since Lum was not "white," then she was, by definition, "colored." This ruling would strengthen segregation, setting a precedent that wouldn't be overruled for 30 years until Brown v. Board of Education. And while Brown v. Board would overturn segregation in schools, Lum set another precedent in the state's power toward making racial distinctions in school systems that has yet to be challenged.

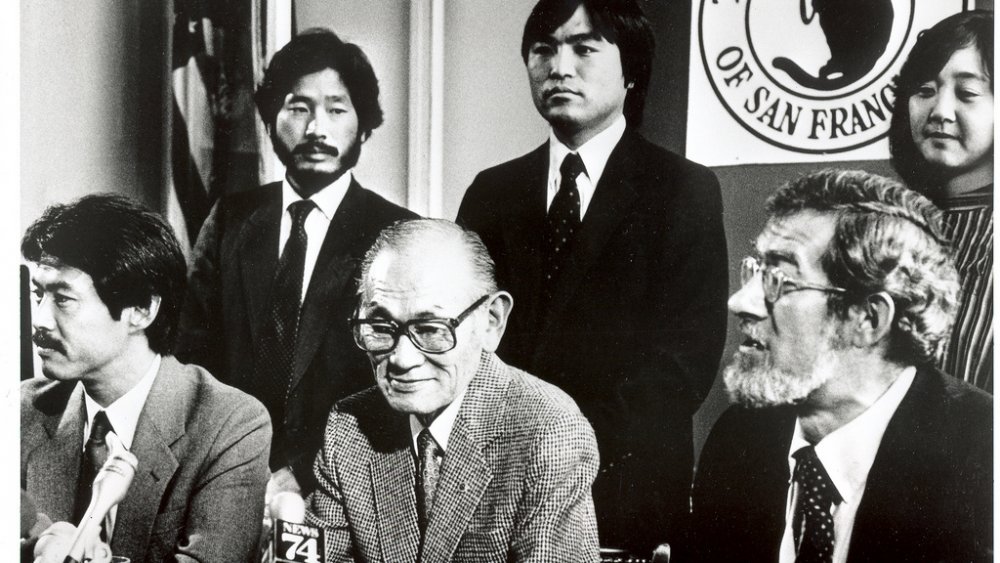

The legality of internment

Three months after the United States declared war on Japan and joined World War II, the US effectively declared war on its residents with Japanese ancestry as well. According to ThoughtCo., Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942, essentially allowed the US military to commandeer land as military zones and force people of Japanese ancestry out. Along with a previous order that restricted the movement of people with Japanese ancestry out of the West Coast, these orders effectively began the forced internment of Japanese people in the United States.

In 1944, Fred Korematsu attempted to avoid the forced internment by changing his name and undergoing facial surgery in an attempt to pass as Mexican American. He was eventually arrested and convicted, and after challenging the conviction in lower courts with the help of the ACLU, Korematsu appealed to the United States Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States.

The Supreme Court would uphold the conviction, deciding that the executive order was constitutional. Though they admitted that there was an infringement on people's constitutional rights, they stated that wartime internment was allowed by the Constitution, being that this was a decision based on military necessity, not race. While the case was reopened in 1983, with a federal judge in a district court overturning Korematsu's conviction, the Supreme Court decision remained until 2018, when it was rejected as part of the Supreme Court ruling in Trump v. Hawaii.

An end to segregation in public schools

By the 1930s, Black organizers were beginning to chip away at the perceived constitutionality of segregated education. In Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma, both of which were heard in 1950, the NAACP was able to successfully challenge the notion of "separate but equal" in graduate studies, setting the stage for Brown v. Board of Education.

In 1951, Oliver Brown filed a class-action lawsuit against the Board of Education of Topeka on behalf of his nine-year-old daughter Linda. According to Teen Vogue, the "separate but equal" ruling led to segregated public schools with drastically different qualities of education, and after Brown was unable to get his daughter into the white school, he sued for her right to a good education. Brown's case was Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, but the ruling known as Brown v. Board of Education was one that consolidated Brown's ruling with five other cases. Thurgood Marshall, who later went on to serve on the Supreme Court himself, had been representing the Browns and argued on behalf of all the cases.

Reaching a verdict was not an easy task. While most of the justices believed segregation was unconstitutional, they couldn't coordinate their arguments by the end of the court's term. The court reheard the case in 1953, by which point Justice Fred Vinson had died and been replaced by Justice Earl Warren. This time, the justices came to a unanimous decision declaring that separate is inherently unequal, fueling the fight for civil rights.

What counts as a fair trial?

Until Hernandez v. Texas, the 14th Amendment was considered to provide protection to Black and white people only. Mexicans were technically considered white, although they experienced segregation akin to what Black people experienced. In the town of Edna, Texas, where Pete Hernandez was tried, no one of Mexican ancestry had served on a jury for at least 25 years. This case would also become the first instance of Mexican American lawyers speaking before the Supreme Court.

According to Tarlton Law Library, Hernandez was accused of murder in 1950 and was sentenced to life imprisonment after being found guilty by an all-white jury. When Hernandez's lawyer Gustavo (Gus) García appealed the verdict, he wasn't contesting Hernandez's guilt but whether or not he'd had his right to a fair trial by a jury of his peers, as accorded by the 14th Amendment. García argued that there was a systematic exclusion of people with Mexican ancestry from juries in Edna, while the state of Texas argued that since Mexicans were considered white, there had been no discrimination.

In the end, García was able to prove to the court that not only where Mexicans considered a class distinct from white, demonstrated by the various instances of segregation, but that the Texas courts had deliberately excluded people with Spanish-sounding names from juries. The Supreme Court would unanimously decide in favor of Hernandez, declaring that the 14th Amendment provided protection from discrimination regardless of racial class or nationality, provided discrimination could be proven.

Civil rights, take two

It was in Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States that the decision of the Civil Rights Cases was essentially overturned. While segregation and racial discrimination had been banned in public places by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many businesses refused to integrate. Many states even continued to pass Jim Crow laws.

According to the Tarlton Law Library, in the case of Heart, the owners of the Heart of Atlanta Motel sued the government, arguing that Congress had no right to regulate interstate businesses. They would also claim that the Civil Rights Act violated their Fifth Amendment rights, since it restricted their ability to choose their own customers. While the suit was about interstate commerce in particular, it would redefine the precedent of Congressional powers.

The justices would unanimously conclude that Congress had acted within their authority — since the hotel was on a highway route, their discrimination would affect interstate commerce. They also concluded that the Civil Rights Act in no way violated the Fifth Amendment. With this ruling, Congress' power to enact anti-discrimination laws was upheld after having been defeated in 1883.

Fight in the name of loving

The ban on interracial marriage was first challenged in 1883 with Pace v. Alabama, although the Supreme Court unanimously concluded that the ban wasn't discriminatory since the punishment was the same for Black and white people. This precedent would hold until 1964, when McLaughlin v. State of Florida would reverse the ban on interracial relationships, paving the way for Loving v. Virginia, which finally struck down the ban on interracial marriage.

Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving were married in 1958 in Washington DC, having had to leave Virginia in order to avoid the Racial Integrity Laws. But when they returned to Virginia after having only been married a few weeks, police raided their home in the middle of the night and accused them of unlawful cohabitation. Despite Loving showing them the marriage certificate hanging on the wall, the sheriff disparaged the certificate, maintaining that it was invalid. According to Time, Jeter didn't even identify as Black, instead identifying as Indian-Rappahannock, and claimed that she informed the police officers of such when they first came to arrest her.

Regardless, the couple ended up pleading guilty and, in accordance with their plea bargain, left the state under penalty of imprisonment. In 1963, Jeter contacted the ACLU, which agreed to pick up the case. With their help, the case made its way to the Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously that the ban on interracial marriage was unconstitutional.