The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Harvey Milk

Harvey Milk is one of the most iconic figures in LGBTQIA history. San Francisco, where he made history in 1978 as the first non-incumbent openly gay man to be elected to public office in the United States, boasts a plaza and an airport terminal named after him. New York has Harvey Milk High School, while Portland, Oregon, has Harvey Milk Street. Paris has a square bearing his name, and the U.S. Navy named a ship after him.

Other posthumous honors include his appearance on a stamp, receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama, and California's designation of May 22 as Harvey Milk Day. He was the subject of the 1984 Academy Award-winning documentary The Times of Harvey Milk, and Sean Penn won best actor playing him in the 2008 biopic Milk. His "Hope Speech" lives on as one of the most exemplary civil rights speeches in American history, and his cry of "you gotta give 'em hope!" appears at the base of his memorial statue in San Francisco's City Hall.

Harvey Milk's life was cut short when he was assassinated on November 27, 1978. His story is both tragic and inspiring; he was a visionary who knew a better world was possible and set out to bring his vision to light. He was known for telling crowds "I want to recruit you!" and to this day activists remain inspired by his words and his life.

Harvey Milk was a funny-looking kid with a secret

Harvey Bernard Milk was born on May 22, 1930, in Woodmere, New York, the youngest son of Lithuanian Jewish parents. As a child, he was teased for his "protruding nose, big nose, and oversized feet," according to LGL, and coped by teasing his tormentors right back and using the classic defense mechanism of weirdos everywhere: taking on the role of class clown. By his early teens, Harvey knew he was gay but kept his sexuality a secret, playing football and basketball and continuing to make people laugh.

He went on to graduate from New York State College for Teachers where he "penned a popular weekly student newspaper column where he began questioning issues of diversity with a reflection on the lessons learned from the recently ended World War" and joined the Navy in 1951.

According to the San Diego Union Tribune, the Navy forced Harvey to resign in 1955 after he was spotted in a San Diego park popular with gay men. From its beginnings, the United States military considered homosexual behavior grounds for dismissal, a policy that didn't ease at all until President Bill Clinton's "don't ask, don't tell" executive order of 1993. Rather than risk getting kicked out and outed as gay, Harvey resigned from the Navy with an honorable discharge, although recent archival research suggests that Harvey may have forged his honorable discharge in order to be employable after his Navy stint and that his discharge was officially considered a middle-ground "other than honorable."

Harvey Milk lived a double life

Once out of the Navy, Harvey took on a variety of jobs, including schoolteacher, insurance actuary, and researcher for a Wall Street firm. His biography The Mayor of Castro Street revealed that Harvey also campaigned for conservative Republican Barry Goldwater's 1964 presidential campaign while secretly pursuing relationships with men, including Craig Rodwell, whom he met while trying to recruit Rodwell as a Goldwater canvasser despite his activity in the gay rights organizations Harvey then avoided. According to his biographer, Randy Shilts, at this point in his life Harvey was a "staunch conservative" and "the raw use of federal power in the economy made [his] blood boil."

When a New York judge gave Rodwell three days in jail for supposed indecent exposure in a park, Harvey, years away from his work as an activist and status as a gay icon, was unhappy with Craig's openness and penchant for attracting police attention and broke up with him. Randy Shilts quoted Rodwell as saying, "Here he had this carefully constructed life. ... He was terrified that someone might find out he was gay because he was going with me, and I was branded." Harvey continuing to stay closeted and keep his gay identity a secret, entirely separate from his professional and family life.

Harvey Milk, the sad-eyed man

San Francisco became a gay hub after World War II as a port city where a large number of men found themselves among other former soldiers, many of whom stayed on in California to create a community away from their families and homes. Harvey and his boyfriend, stage manager Jack Galen McKinley, arrived in San Francisco in 1969 with the touring company of the musical Hair. Despite his countercultural affiliations, Harvey got a staid job at an investment firm; he was soon fired for growing his hair long.

He drifted around the country for a time, eventually ending up back in New York with Jack McKinley. A 1972 New York Times article that discussed Jack's work on the Broadway production of Hair described Harvey as his "long-time friend and general aide" and "a sad‐eyed man—another aging hippie with long, long hair, wearing faded jeans and pretty beads." His transformation from a conservative Goldwater supporter to a wandering hippie was an extreme and complete 180 degrees turn, but in the words of Randy Shilts, "when Harvey did something, he did it all the way. Though friends of the Wall Street Milk could not imagine Harvey the Hippie, friends of the new Milk had a hard time imagining how he could ever have been straighlaced."

Harvey became disillusioned and ready to act

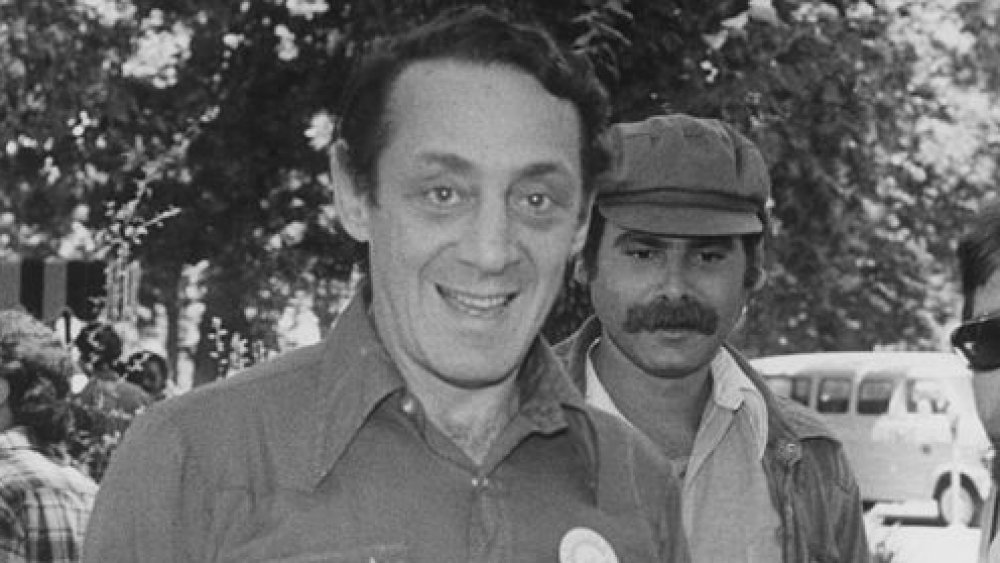

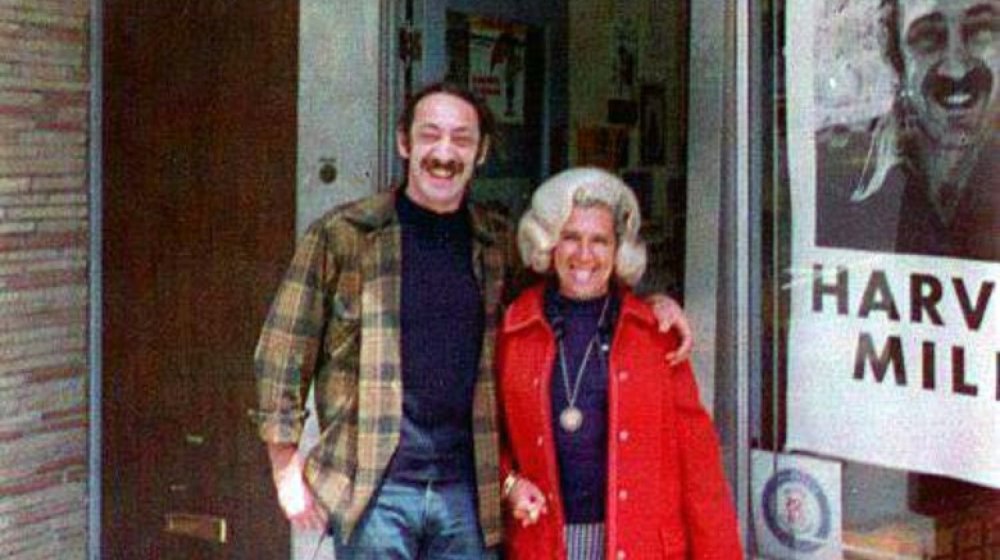

Harvey eventually drifted back to San Francisco and took a job as a securities analyst. When his job was eliminated in a merger, he came out as a gay man: "It wasn't a difficult transition. It was easier than I expected. ... I realized I no longer had to lead a double life with double standards." He opened a camera store on Castro Street (pictured above with his sister-in-law), the heart of San Francisco's gay community, little knowing his status as "another aging hippie" was about to dramatically change forever.

His return coincided with the growing gay community of San Francisco reaching a breaking point and fighting back against homophobic laws, police persecution, and rampant entrapment that tricked gay men into getting arrested in public parks, just like Harvey's ex Craig Rodwell. Harvey Milk entered into the political arena in 1973, inspired by his frustration at the amount of taxes he had to pay as a business owner (perhaps a callback to his past as a conservative who didn't like government involvement in business matters) as well as his anger at the United States involvement in the Vietnam War and the federal government's refusal to give honest answers during the Watergate hearings. In 1978 he told the San Francisco Examiner, "I finally reached the point where I knew I had to become involved or shut up."

The 'aging hippie' ran for office and lost

Harvey ran for city supervisor of San Francisco in 1973. His campaign was met with distrust from the local gay political establishment, who saw him as coming out of nowhere without the years of activism and coalition-building put in by other, more successful politicians. As a 1986 article in The New Yorker explained, "They did not need an aging hippie who had just arrived in town and was running a camera store in the Castro." Harvey lost his run but won the most votes in the gay neighborhoods of the Castro and Polk Street. Harvey later estimated via precinct counts that between 25,000 and 30,000 gay people lived in the Casto area by 1977. Four years earlier, Harvey at the age of 43 found his calling as a politician and found his core group of supporters at the same time.

Eager to be taken seriously as a politician, he cut his hair, stopped smoking weed, and vowed to quit visiting gay bathhouses. He also started calling himself The Mayor of Castro Street, a nickname that follows him to this day and is the title of the 1982 Milk biography by Randy Shilts. He began building coalitions within organized labor groups and unions and founded the Castro Village Association with other gay business owners. Although another run in 1975 was also unsuccessful, this period saw Harvey's first affiliation with San Francisco Mayor George Moscone; they would eventually be forever linked for horrifying, tragic reasons.

Harvey Milk made history, kept losing

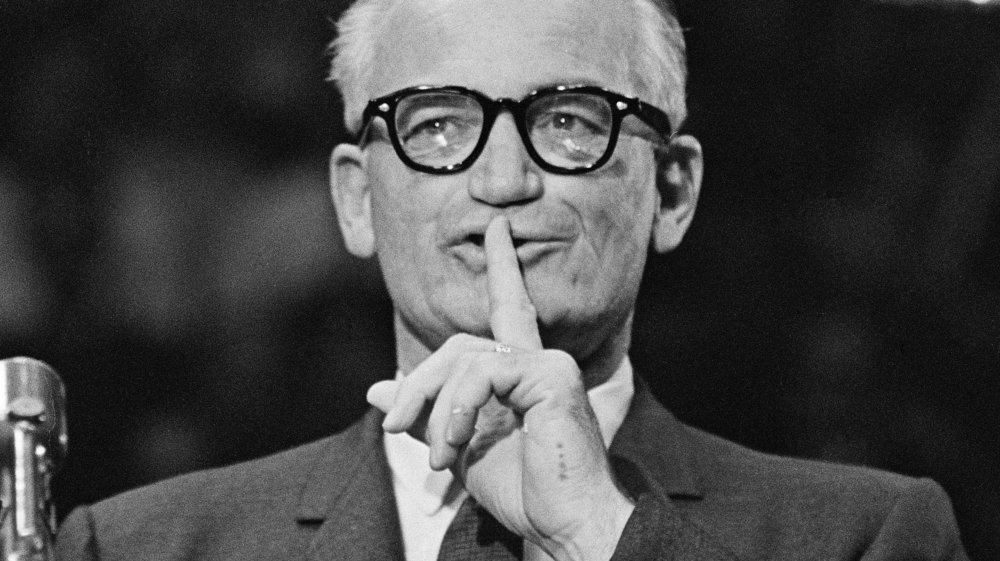

As a state senator, George Moscone (above) had been instrumental in getting rid of a California law that defined sodomy as a crime. When he won his mayoral race, he thanked Harvey personally for his support, acknowledged his positive influence in his campaign, and in 1976 appointed him to the city's Board of Permit Appeals, making Harvey Milk the first openly gay city commissioner in the United States. Five weeks later, Harvey announced that he would run for California State Assembly, forcing Moscone to fire him.

He ran as a political underdog, calling more established gay politicians "gay Uncle Toms," claiming to be shut out by the local Democrats, and using the slogan "Harvey Milk Versus The Machine." When Harvey's friend Oliver "Bill" Sipple stopped an assassination attempt against then-President Gerald Ford, Harvey contacted the San Francisco Chronicle, and, according to the Los Angeles Times, called Sipple a hero and outed him without permission in an attempt to "show people that not everyone who was gay runs around with lipstick, high heels and a dress." This brought nationwide attention to both Harvey and Sipple, which was a benefit to Harvey's political career but caused the closeted Sipple distress and rejection from his family. Harvey lost his run for State Assembly with one opponent calling Harvey "a downer. ... You talk about how you're gonna throw the bums out, but how are you gonna fix things — other than beat me?"

An explosion of homophobic violence

Harvey Milk's third run for San Francisco city supervisor in 1977 coincided with a nationwide uptick in homophobic rhetoric and organizing. When gay activists in Miami won a civil rights ordinance that made discrimination based on sexual orientation illegal, a group of fundamentalist Christians organized a counter-campaign led by activist Anita Bryant (pictured) called Save Our Children, leading to a vote that overturned the ordinance. In the course of Bryant's homophobic campaign, she and her supporters reportedly told "vicious lies" about gay-friendly San Francisco in order to scare Miami residents into voting against gay rights. San Francisco Sheriff Richard Hogisto went to Miami to campaign for gay rights and told the San Francisco Examiner that the ordinance's repeal "just shows that witch-hunting can still be successful."

The night of the vote, the San Francisco Examiner reported that Harvey joined an impromptu 5-mile protest march through the city, declaring, "This is the power of the gay community! Anita's going to create a national gay force!"

Nationwide, voters overturned civil rights ordinances similar to Miami's. California State Senator John Briggs wrote a bill banning gay and lesbian teachers in public schools and held a press conference calling the city "a sexual garbage heap." Random attacks against gay men broke out in the Castro, and a man named Robert Hillsborough died when attackers surrounded him yelling gay slurs and stabbed him 15 times. San Franciscans responded by holding the 1977 Gay Freedom Day Parade, attended by 250,000 people.

Victory at last!

Harvey Milk's third run for City Supervisor was the charm. His primary opponent, Rick Stokes, also an out gay man, had said, "I'm just a businessman who happens to be gay." Harvey was less concerned with appealing to straight voters and told The New York Times, "We don't want sympathetic liberals, we want gays to represent gays. ... I represent the gay street people — the 14-year-old runaway from San Antonio. We have to make up for hundreds of years of persecution. We have to give hope to that poor runaway kid from San Antonio. They go to the bars because churches are hostile. They need hope! They need a piece of the pie! ... Gay rights protect everyone."

On November 8, 1977, Harvey Milk was elected city supervisor over 16 other candidates. He arrived at his camera shop on the back on a motorcycle, escorted by Sheriff Richard Hongisto, accepted a bouquet of pink roses, and told a cheering crowd of supporters "All I can say is, it means hope."

When Harvey Milk was sworn in as San Francisco City Supervisor on January 9, 1978, he made history once again by becoming the first non-incumbent openly gay man to win an election for public office in the United States. He walked to City Hall for his swearing in ceremony with his boyfriend, Jack Lira, and was quoted as saying, "You can stand around and throw bricks at Silly Hall or you can take it over. Well, here we are."

Harvey Milk's civil rights bill

The New York Times reported that Harvey almost immediately sponsored a civil rights bill that outlawed discrimination in San Francisco based on sexual orientation; all but one member of the Board of Supervisors voted in favor of the bill and it was enacted as "the most stringent and encompassing [such law] in the nation," with Harvey explaining, "this one has teeth; a person can go to court if his rights are violated once this is passed." He also drew nationwide attention to himself and to San Francisco by enacting the infamous "pooper scooper" law that required dog owners to clean up after their dogs in public.

Harvey also advocated for day care centers for working mothers, affordable housing, tax code reform, and improved civil services for the Castro district. It wasn't all pink roses, though. Harvey disagreed with fellow City Supervisor Dan White on the placement of a mental health facility scheduled for placement in White's neighborhood, causing White to oppose every one of Harvey's initiatives. Then, on August 28, 1978, Harvey's boyfriend, Jack Lira, hanged himself in Harvey's apartment and left a note stating he was upset by homophobic campaigns such as those by John Briggs and Anita Bryant.

if you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Harvey Milk remained independent in the face of death threats

Harvey began receiving death threats when he ran for the California Assembly and lived with the assumption that he would be assassinated. Reporter Lenny Giteck quoted Harvey in the San Francisco Examiner as saying that "Any openly gay politician has to expect it and learn to live with it." Tapes that Harvey made after his election in late 1977 laid out his requests in the event that he was murdered.

None of this kept him from speaking out against John Briggs's bigoted Proposition 6. Dubbed the Briggs Initiative, the proposed California law would have mandated the firing of gay teachers and any teachers who supported gay rights. Harvey attended every Briggs rally and held debates using statistics and one-liners to fight back against claims that homosexuals sought to abuse and "recruit" children, including the particularly quotable quip, "If it were true that children mimicked their teachers, you'd sure have a helluva lot more nuns running around!"

In 1978 Harvey "ignited the crowd" at the 1978 San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade and asked President Jimmy Carter to speak out against Briggs. He also noted the importance of electing gay politicians: "The first gay people we elect must be strong. They must not be content to sit in the back of the bus. They must not be content to accept pablum. They must be above wheeling and dealing. They must be -– for the good of all of us -– independent, unbought."

Harvey Milk's day of death

President Carter did eventually voice his disapproval of the Briggs Initiative. On November 7, 1978, voters defeated the proposition by over a million votes, a resounding victory for gay rights and for Harvey Milk as a politician.

Three days later, Dan White, the city supervisor who considered Harvey a rival, quit his position. He immediately attempted to withdraw his resignation, but "opposition to him had developed in his ethnically mixed district, and the affable but politically shrewd Mayor Moscone had decided it would be smarter for him to appoint a more compatible, liberal man to White's position on the board." According to Time, on November 27, 1978, White entered City Hall through a basement window, went to Moscone's office, and shot Moscone dead. White then intercepted Harvey in the hall and shot him in the head, killing him.

Murdered at the height of his popularity, Harvey Milk's assassination is forever entwined with his historical election. We'll never know what he could have become if he had lived to have a longer political career. Nevertheless, his work lives on. Writer John Cloud observed in 1998, "It's a mistake to see his central legacy as political. Rather, his most consistent message was social, even psychological: Come out, stop lying, screw what everyone thinks." Today, Harvey's nephew Stuart Milk and his former campaign manager Anne Kronenberg run the Harvey Milk Foundation, which seeks "to empower local, regional, national and global organizations so that they may fully realize the power of Harvey Milk's story, style, and collaborative relationship building."