The Messed Up Story Of Wounded Knee

The history between the United States and Native Americans doesn't make the US look like the shining hero it pretends to be. The parts of history that point to the country's near-genocide and mass murders are rarely talked about in classrooms below the collegiate level. If they are, they're usually touched on in the briefest possible manner or absolutely twisted to cover up the nation's dark past so as to keep from tainting young minds' feelings about the ol' red, white, and blue. The truth is much darker. It includes things like Manifest Destiny, invasion, and murder. It includes travesties such as the killing of tribal leaders and forced assimilation.

To understand the events that happened at Wounded Knee, the massacre of 1890 and the occupation of 1973, it's important to know that no country is great, and every nation has committed atrocities. That's no excuse, though. Hopefully, knowing the messed up history of Wounded Knee and the US government's actions toward the Sioux people will build compassion for the struggles indigenous Americans still face today.

Seizing Sioux lands

How US lands came to be the large swath of North America that they are today, situated snugly between Canada and Mexico, should be a story every American knows if they don't already. That history is one of theft, broken treaties, and near-genocide. It's not some heroic story about the indigenous people giving over their homes warmly during some fantastical Pilgrim-Native American Thanksgiving. In fact, it's nothing like what you learned in kindergarten at all.

When westward expansion began, native tribes were pushed off their lands onto reservations, if they weren't outright murdered so that the invading US government could take what they wanted: land and resources. The Sioux fought to keep their traditional ground and gave the colonizers plenty of trouble, you know, because their lives literally depended on it. Well, it was enough trouble for the Sioux to force 60 million acres of land in South Dakota from the US government. The pact was signed with the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

The Treaty of Fort Laramie would be broken after gold was found in the Black Hills. Settlers were invited to pull up some land and start digging. The Sioux fought back, but there wasn't much they could do against the colossal colonizer force. The original 60 million acres promised would be cut down to roughly a third of that by 1877 and then again to 12.7 million as of 1887, according to Britannica.

The Ghost Dance movement

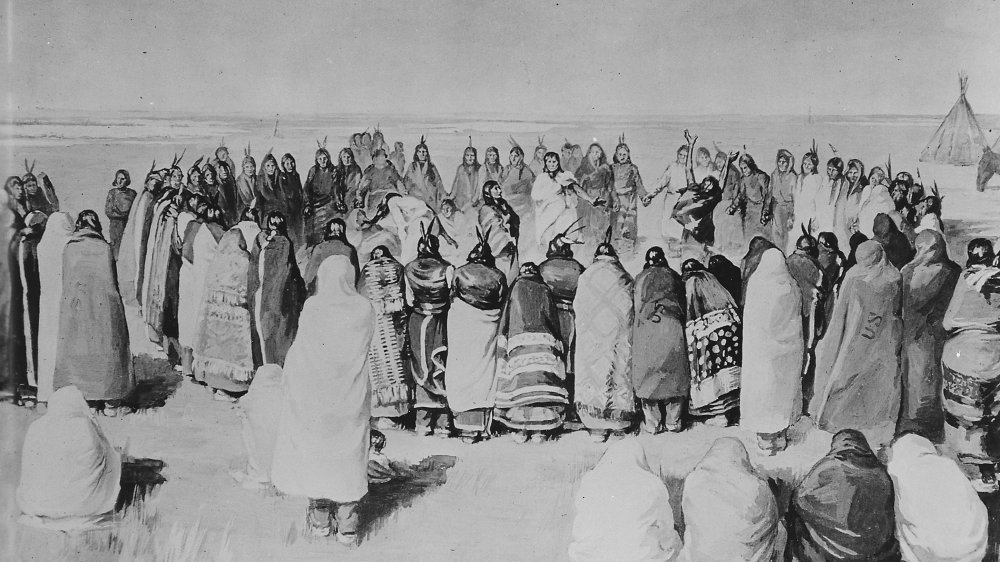

The Ghost Dance was inspired by both indigenous traditions and Christianity. It weaved together stories of a messiah and a supreme being, as was seen by Wovoka, the second Ghost Dance prophet, while promising the original people of the land a way back to a life without colonizers. The movement was said to have the power to rid the land of the white invaders and bring the native dead back to life, according to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Peace would reign, fauna would flourish, and the buffalo would return to their former glory. The movement spread from the west through the Great Plains.

The Ghost Dance movement had US officials on edge, to put it lightly. Sure, most of them probably didn't believe in the superstition and magic that surrounded the ceremony and its movement, but the sheer spirit of rebellion if sowed, though intended to be peaceful, could put a serious damper on the government's plans to dominate the native people. The last thing they needed was for the tribes to cling to their traditional ways and cause more resistance, so they fought it every chance they got. It's one of the reasons they went after Sitting Bull despite the fact that he'd surrendered. His word, added to the invigorating spirit that followed the Ghost Dance movement, could have easily started another uprising. It also factored into the massacre at Wounded Knee.

A false prophet?

There was more than one Ghost Dance prophet and more than one iteration of the movement. The first was led by Tävibo of the Paiute. The second prophet, Wovoka, was also of the Paiute tribe and claimed to be Tävibo's son. Wovoka revived the Ghost Dance movement for its second life, but he was a controversial figure. Some traditionalists would say he was a false prophet.

Wovoka grew up on a ranch working for a white family, doing white things, and being exposed to white religion (Christianity). At the time, this was a common tactic to assimilate the native people and kill off their traditions. Christianity would influence Wovoka's Ghost Dance movement, but Wovoka wasn't without his native traditions, either. He was a "weather doctor," or shaman, according to the University of Michigan. After a vision in which Wovoka met God and saw the indigenous dead return to life, he set out to revive the movement.

Peace was at the core of Wovoka's teachings. He preached nonviolence, urging the native people not to fight with the whites. He went so far as to tell his followers not to "make any trouble" for the whites or refuse to work for them, according to PBS. Many at Wounded Knee were influenced by his teaching, and many at Wounded Knee refused to fight as they were slaughtered. Wovoka refused to comment on the massacre afterward, but the Ghost Dance movement died publicly at Wounded Knee.

Disarming the Lakota camp

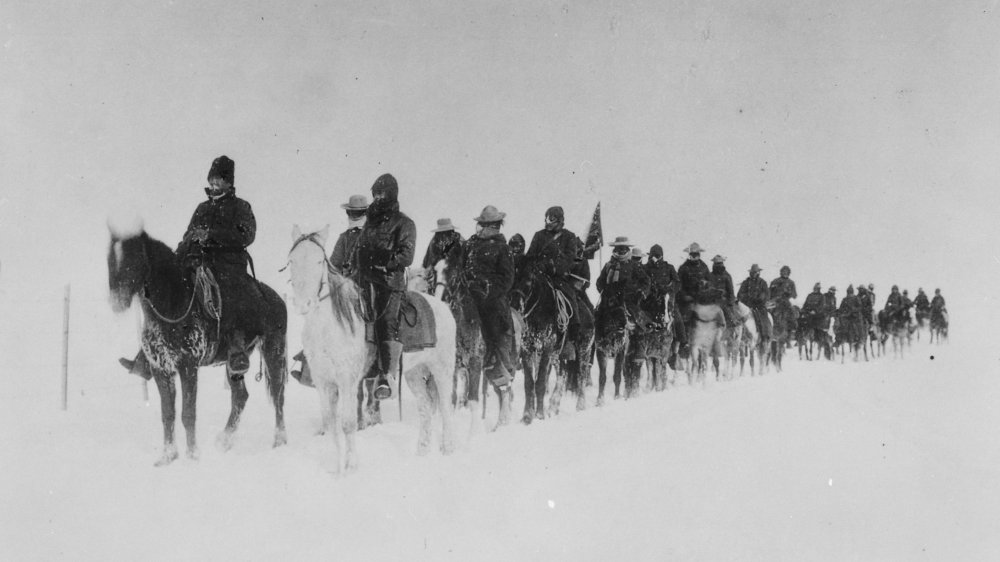

There were about 350 Lakota, a tribe that was part of the Great Sioux nation, camping at Wounded Knee creek. According to Jacobin Magazine, the US 7th Cavalry had marched them there and forced them to stop for the night. The band had fled the Standing Rock reservation after Sitting Bull was killed. They were searching for protection at the Pine Ridge reservation along Wounded Knee Creek, according to the Digital Public Library of America.

The soldiers who caught up to the Lakota were said to have been sent to disarm the band and arrest Big Foot, one of Sitting Bull's followers. From there, the Army would escort the Lakota to Fort Omaha, where they'd be imprisoned. They didn't want to risk them meeting up with Red Cloud and his people at Pine Ridge. There's just one problem: If their true intentions were to peacefully disarm and arrest the Lakota band, why did they show up with such an overwhelming and heavily armed force? They had Hotchkiss machine guns set up around the camp before they started disarming the native people, according to Britannica. Seems like a bit of overkill for 350 people, mostly women and children, who were starving at the time.

A brief scuffle

The Lakota were woke by the 7th Cavalry, who demanded that they hand over their weapons. Big Foot partially complied, giving the Army some of the band's firearms as a sign of good faith, but the soldiers weren't convinced. The Army started rifling for rifles — every inch of the camp, and every person within, would be searched. The indigenous people, on the other hand, were tired of being searched.

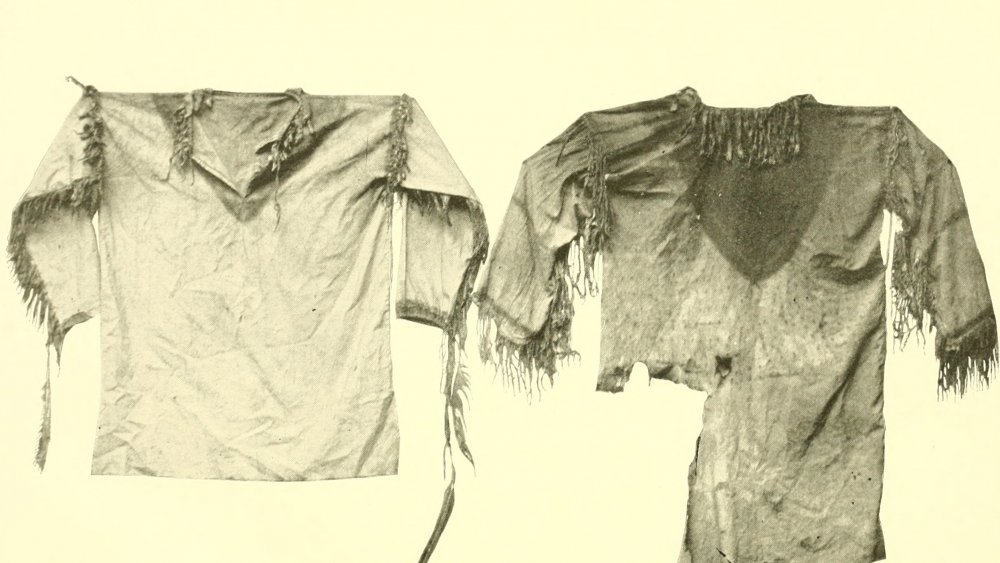

One member of the band, Sits Straight, took up the Ghost Dance and called for others to join in, according to Britannica. Wovoka's Ghost Dance included ghost shirts that were said to protect the wearer from bullets, and Sits Straight had a feeling they'd need that protection. Unfortunately, the powers of the Ghost Dance wouldn't protect the dancers but, instead, make the soldiers more nervous as the dance intensified throughout its performance.

The cavalry was still disarming the other members of the band while the dance was going on. Black Coyote, who was reported to have been deaf, refused to relinquish his rifle. Accounts of the exact interaction differ. Some claim he didn't want to give up the rifle because it was expensive, while others say he couldn't understand English and was unable to communicate with the soldiers. One thing all accounts agree on is that a struggle ensued, and Black Coyote's gun shot into the air, signaling the onset of one of the worst tragedies to take place on American soil like a morbid start pistol.

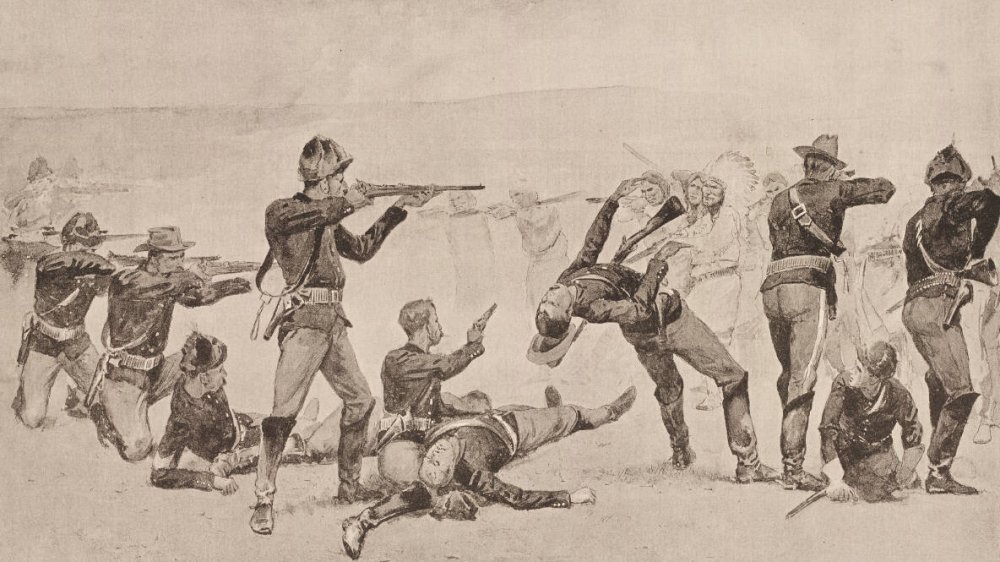

A violent massacre

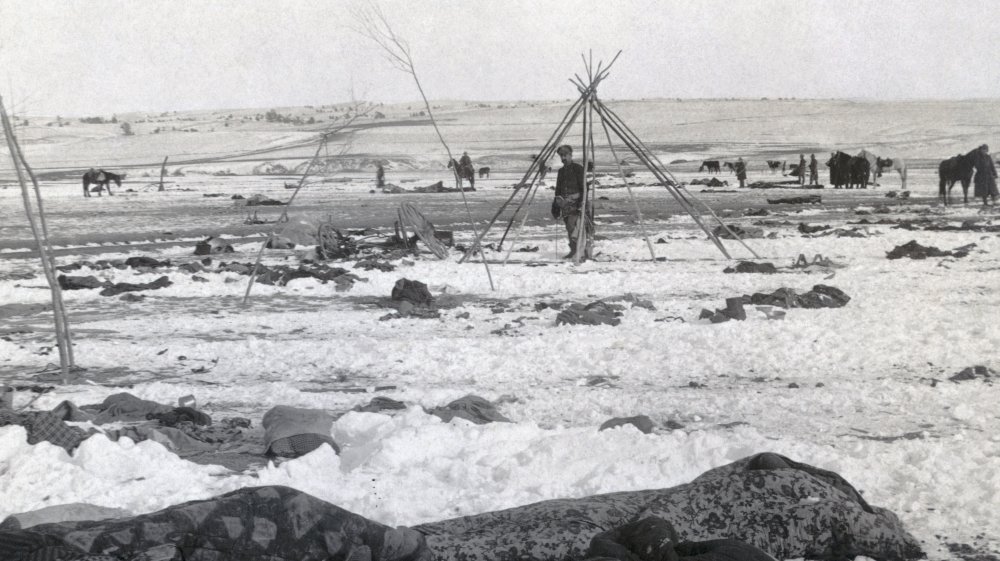

When the firing started, it was brutal. Many of the native warriors had already been stripped of their guns, and there weren't many to begin with. Maybe 100, 120 at most, of the 350 were men. The rest were women and children, who had been separated from the men during the disarming. The first volley was fired point-blank. The cavalry killed half of the men, including Big Foot, but the soldiers weren't satisfied. They were full of bloodlust and cruelty, and they weren't going to stop until they killed everyone they could, so they headed for the women and children.

The four Hotchkiss machine guns rained down deadly drops of hot lead into anyone within range. Men, women, children — it didn't matter. If they were native, they were on the US Army's kill list. The troops had the camp surrounded on all sides, and they were prepared for murder. Soldiers tracked down those who fled and butchered them. There are accounts of frozen infants being found in the arms of their murdered mothers. Most of the Lakota were unarmed, sick, and starving. Only 25 US troops were killed that day, while between 150 and 350 Native American bodies would be buried in a mass grave, according to The Guardian. December 29, 1890, wasn't a battle. It was a massacre.

Bodies were stripped and looted

In a disgraceful move that added insult to, well, murder, the bodies of the dead Lakota were stripped of anything the soldiers might have thought was valuable. The looted items were kept as souvenirs or sold to collectors, according to Indian Country Today, sometimes advertised in local newspapers. Ghost shirts and other sacred items found their way into private collections or into personal households as wall decor. Today, many of these stolen items have been recovered and either given back to their people or placed in museums, but at the time, the looting set a precedent for the aftermath.

Not only were items looted, but people were taken as well. Members of the Ghost Dance movement who had been imprisoned were released to entertain the white public who, as disgusting as it is, reveled in the death of Native Americans. For pocket change, you could witness Ghost Dance leaders paraded around Buffalo Bill's Wild West show's arena, replaying the tragedy so spectators could cheer. All in all, American businesses capitalized on the murder of hundreds of native people to increase their profits.

Soldiers were awarded Medals of Honor

The Medal of Honor is one of, if not the, highest military honors you can receive in the United States. According to the US Army Center of Military History, around 3,400 Medals of Honor have been awarded to "the bravest soldiers" in US history, which doesn't seem entirely true, since they handed out 20 to members of the 7th Calvary who were present at the Wounded Knee Massacre. That's right, 20 soldiers were inducted into "the bravest" for slaughtering unarmed, sick, and starving "opponents" who were actively fleeing.

Native Americans, along with anyone else who knows what the word "honor" means, have been fighting to get these medals stripped essentially since they were awarded. In 1990, 100 years after the Wounded Knee massacre, Congress stepped into "action" and apologized, but they still didn't strip the medals away. In 2019, a House bill was proposed to get rid of these shameful medals once and for all, but as of this writing, it hasn't been passed. According to The New York Times, 900 medals have been stripped following legislation in 1916, and not a single one was from the 7th Cavalry at Wounded Knee.

The public had the wrong response

The general response to the Massacre at Wounded Knee among the white public at the time was appalling. The Khan Academy says the mood of mainstream society was favorable toward the slaughter. It's no wonder, though. News of the incident had spread throughout the country, but most of the newspaper articles sided with the 7th Cavalry, reporting that the Army had been forced to take action against a violent uprising. This way of thinking, the "American Indians are trying to kill us" mindset, had been pounded into society essentially since the government decided it wanted the American lands for itself.

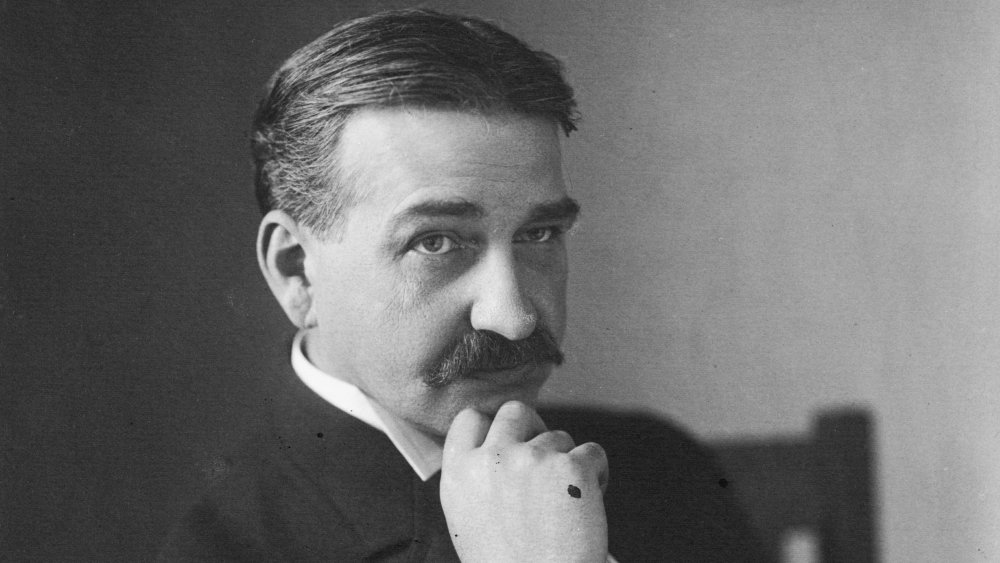

L. Frank Baum jumped on the anti-Indian bandwagon. You might know Baum as the author of The Wizard of Oz. The guy had some racist leanings to begin with, but he grew more vocal following the news of the Massacre at Wounded Knee and the killing of Sitting Bull, according to NPR. After that news had reached his ears, he decided to write a bunch of editorials calling for the complete extermination of indigenous Americans. Baum claimed white people had won the land through conquest and would be safest if they killed off every last one of its native inhabitants. Unfortunately, this idea of conquest over the Native Americans hasn't been totally overcome in modern society, either.

The Wounded Knee Survivors Association

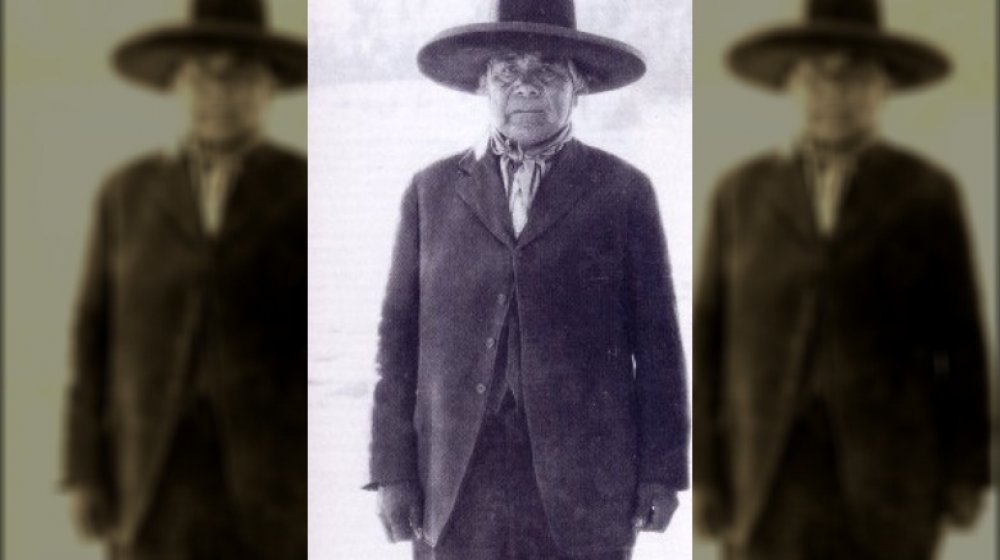

As is expected, the survivors of the Wounded Knee Massacre and their families started looking for compensation shortly after the massacre, though there's no real compensation that amounts to replacing your dead loved ones. It was this need that birthed the Wounded Knee Survivors Association in 1901. The founding members include Dewey Beard, who was the last living survivor from the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and Joseph Horn Cloud, son of Chief Horn Cloud. Chief Horn Cloud was one of the victims of the Wounded Knee Massacre.

The association fought for Congress to grant hearings to those affected by the massacre since they were labeled as "hostiles" and therefore not in any position to receive the benefits granted by the Sioux Depredations Act of 1891. The act basically allowed native tribes to sue for reparations of a sort as long as the government deemed them amicable. Several hearings, ranging from 1939 to 1991, amounted to squat, according to the Museum of the American Indian. In fact, there have been no reparations paid for the Wounded Knee Massacre. The association was successful, though, in getting some of the looted items back.

Tensions build toward another incident at Wounded Knee

To set the stage, the US government was really good at breaking treaties with indigenous American tribes, and those tribes didn't like it. Why would they? The broken treaties translated into a loss of land, brutality against Native Americans, the government stepping all over the already disparaged reservations, and so on. So, a group of indigenous Americans got together in 1968 and formed AIM, the American Indian Movement. AIM was a militant civil rights organization set to combat police brutality and the rampant poverty that afflicted reservations. One could argue that this poverty existed by design. Anyway, AIM still exists as a smaller organization, but its national leadership dissolved in 1978, according to Britannica.

On the Pine Ridge reservation in 1973, there was a bit of internal turmoil. For starters, the reservation was in economic hardship. For enders, many of the Oglala Lakota believed the tribal chairman, Dick Wilson, to be corrupt. According to The Atlantic, the tribe turned to AIM for help after failing to impeach Wilson. Mix all of these factors together, and you get an idea of why AIM and the Oglala Lakota activists made their next move.

A 71-day occupation

The Oglala Lakota activists, with the American Indian Movement in tow, moved into the town of Wounded Knee on February 27, 1973, where they would stay for 71 days. The occupation would look more like a war to anyone paying attention. The activists within the post were surrounded by law enforcement and the FBI, but they'd hold their ground, demanding the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie be acknowledged.

The scene got intense. The town was blocked off, and fire was exchanged from both sides. In total, two people were killed, and 15 were wounded. Anti-siege tactics were deployed as the FBI tried to cut off food supplies and utilities running to the town, according to The Atlantic. Outside activists smuggled them in anyway.

There were several negotiations throughout the occupation. It finally ended on May 8 when the activists surrendered. AIM wanted to continue the occupation, but the Oglala had seen enough bloodshed and wanted it to be over. In all, 1,200 activists were arrested, according to Indian Country Today, but most of the charges were dropped after the FBI was caught manipulating witnesses. The siege would go on to be remembered as the Wounded Knee Incident or the Occupation of Wounded Knee.

Wounded Knee occupants tried to become a sovereign nation

Some of the Oglala Lakota activists in Wounded Knee during the occupation tried to declare themselves a sovereign nation. They pleaded with the United Nations for help, claiming they were a sovereign people whose land was enclosed by that of the United States, which isn't entirely false. The activists announced plans to send delegates to the UN and even asked the UN how to go about doing so. When the United Nations responded, they simply told the activists they'd need to apply for membership as a state through the UN Security Council, but they never explained how to go about it.

The thing is, members of the tribe are technically sovereign people living in sovereign areas surrounded by United States land via treaties signed between the tribal nations and the US. The problem is in the definition, which seems to mean whatever the US decides happens to fit their interests at the time. So, yes, they are sovereign. The US just doesn't care, which is obvious if you look through the numerous treaties broken by the United States.