The Crazy True Story Of Abolitionist John Brown

Pre-Civil War abolitionist John Brown has a reputation that precedes him. As a leader who was willing to take lives to end slavery, Brown often elicits strong opinions. In some circles, he is known as a delusional madman and a zealot who set back the cause for abolition with his needless violence. For others, John Brown is something of a folk hero who finally catalyzed the efforts to free enslaved Americans. Malcolm X once said you could use the public opinion of John Brown as a sort of test: "If a white man wants to be your ally, [ask him] what does he think of John Brown?"

What is undeniable, however, is that John Brown talked the talk and walked the walk. Brown popularized the idea of militant insurrections and drove a wedge between Americans who called for abolition and those who called for appeasement with slaveholders. Even after his death, Brown's legend lives on. As Union soldiers marched into battle during the Civil War, they honored the radical abolitionist with the stirring tune "John Brown's Body," which is still played today.

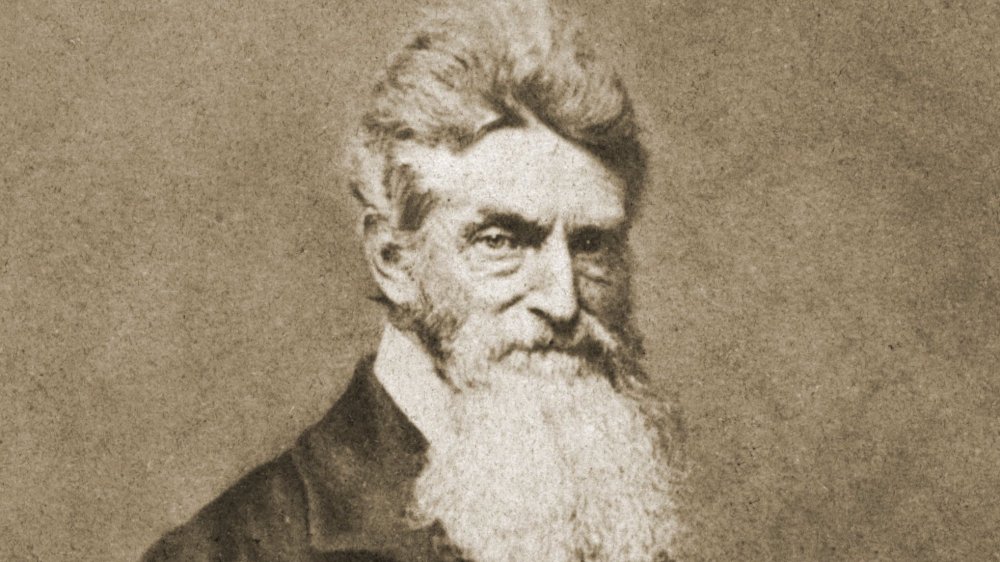

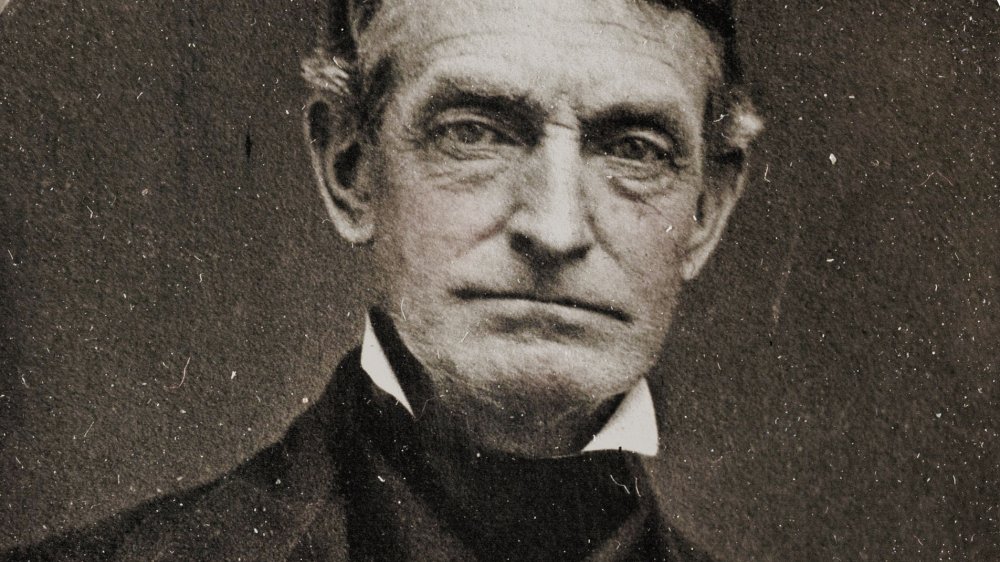

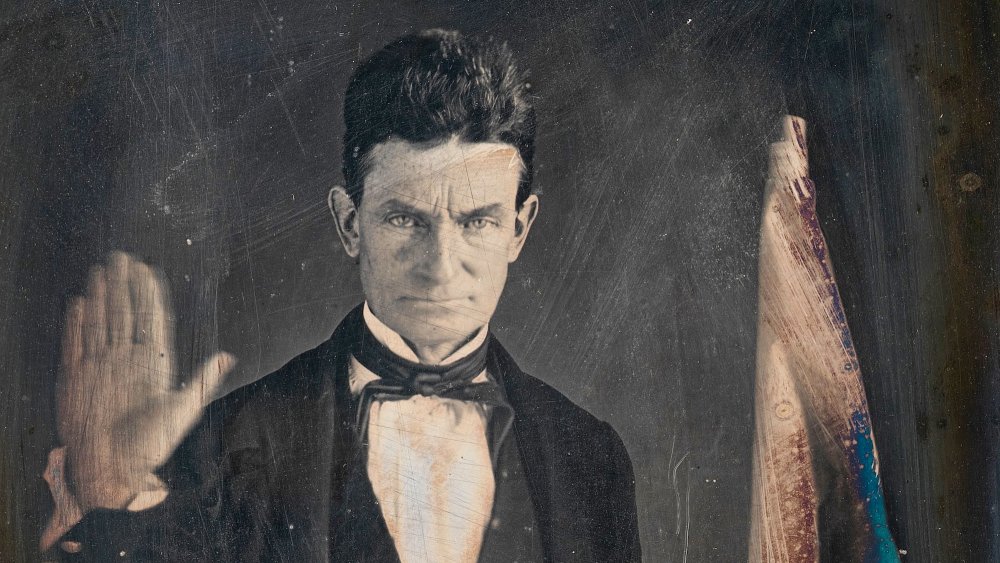

Here is the history of the wild-bearded, fiery John Brown, who believed he was charged by God to end slavery and whose 1859 raid on the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, led him to be the first American hanged for treason.

John Brown was born to abolitionists

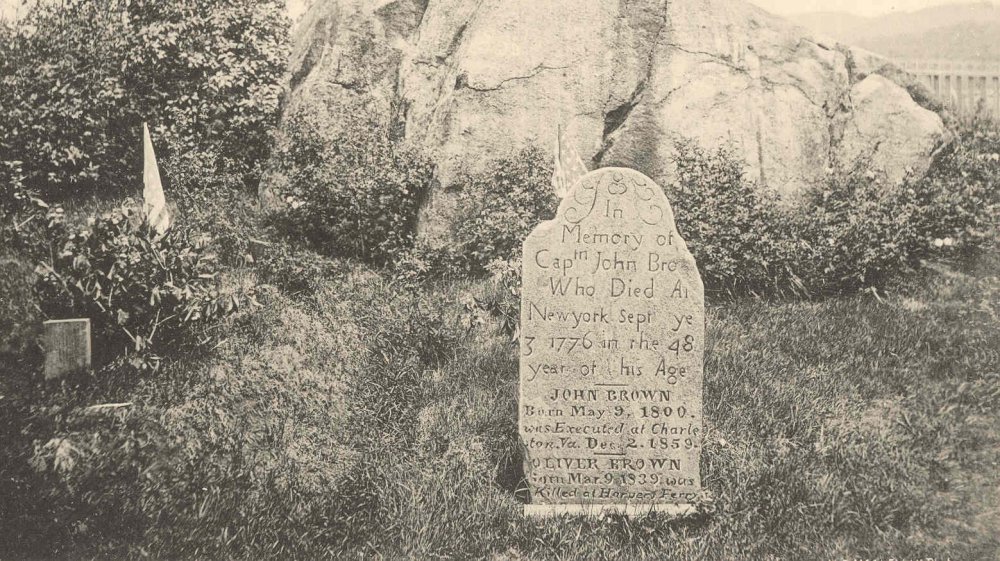

John Brown was born on May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut, and was the son of an abolitionist tanner. The Browns were strict Calvinists and believed enslaving people was a sin against God. Owen, John Brown's father, moved the family to Ohio and helped shelter escaped enslaved people in the Underground Railroad. As Yale University professor David Blight notes, Brown witnessed an enslaved boy being beaten at age 12, and that moment solidified Brown's conception of the horrors of slavery.

John Brown, who would eventually stand over 6 feet tall and sport a long beard, heard a messianic calling. He grew extremely devout and, at age 16, enrolled in a Connecticut prep school in hopes of becoming a Congregationalist minister, as told by the Kansas Historical Society. However, that never panned out.

Instead, Brown married young at the age of 20 on June 21, 1820. With his wife Dianthe Lusk, Brown brought up seven children in Pennsylvania, where they raised cattle to make money. After his wife died in 1832, Brown married Mary Ann Day in 1833. Together, Day and Brown had 13 more children. John Brown fathered a total of 20 children. Sadly, as was common of the period, nine died in infancy.

John Brown was bankrupt

You could say John Brown was something of a jack of all trades, master of none. After ditching the idea of Congregationalist ministry, from the period of 1820 to 1855, John Brown attempted no less than 20 different business ventures. Brown tried to be a tanner, wool merchant, sheep driver, land surveyor, and farmer, among other things. He ping-ponged around the country, living in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, and Kansas. Still, most of John Brown's career ventures ended in failure. Brown's family struggled to make ends meet, and he was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1842 and faced about 20 lawsuits, per History. Brown even spent some time in debtor's prison, as Professor David Blight cites.

What kept John Brown afloat despite his poverty? What led him to eventually take up the mantle of radical abolitionists in the pre-Civil War United States? John Brown had a fervent religious conviction and moral severity. Brown believed in an Old Testament, eye-for-an-eye kind of justice. For Brown, slavery was against God's law, and the only way to eradicate slavery would be for a revolution to take place. Despite this conviction, it took a horror on the national stage in 1837 for Brown to formally align himself with the abolitionist movement.

A turning point in John Brown's life

In 1837, the murder of Elijah P. Lovejoy, an abolitionist and journalist in the free state of Illinois, by a pro-slavery white mob ignited something in John Brown. From that point forward, Brown swore he would take personal action to abolish slavery, as told by the Kansas Historical Society. Reportedly, Brown rose in a meeting after the murder and declared, "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!" as recorded by West Virginia Archives & History.

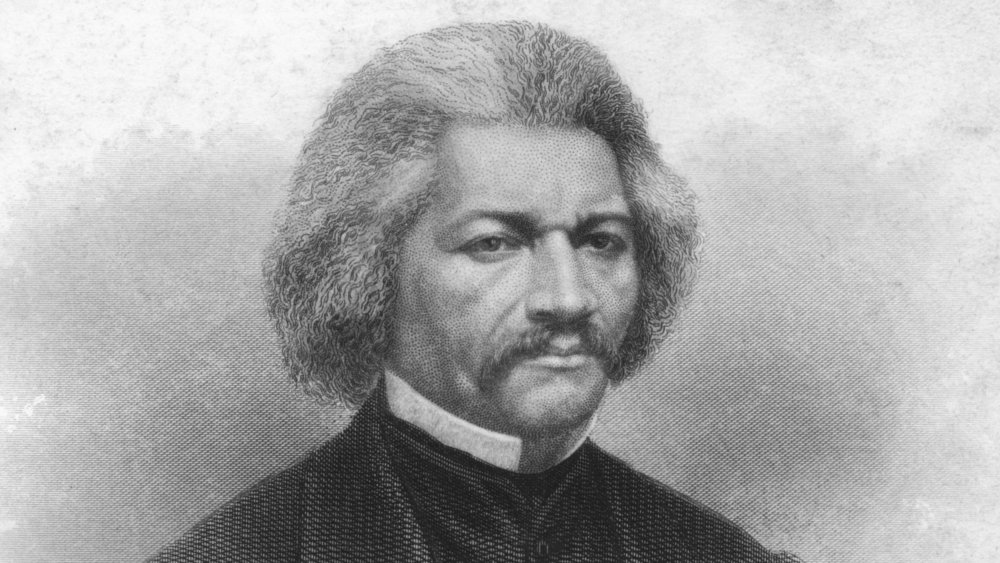

Brown then moved his family to Springfield, Massachusetts, which had proximity to the abolitionist cause and where he saw speakers such as Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth regularly. In 1847, John Brown personally met Frederick Douglass for the first time and floated his plans for a war to end slavery. Douglass later stated that "though a white gentleman, [Brown] is in sympathy a black man, and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery," according to PBS.

John Brown joins a farming community

In 1849, John Brown relocated yet again to North Elba, New York, which, at the time, was offering land grants to African Americans. The Timbuctoo farming community, run by abolitionist Gerrit Smith, was giving out at least 50 acres of land to Black families so they could clear and farm them. Though it was the deep wilderness, families were attracted to the prospect of land and a house of their own. Because land ownership was a pathway to voting rights at the time, a goal of Timbuctoo was to eventually boost Black Americans' right to vote, per History.

Though John Brown wasn't Black, of course, he still felt called to the Adirondack region. As reported by the National Park Service, he bought 244 acres of farmland near Lake Placid so he could serve as something of a mentor and father figure for the Black farmers. Here, Brown surveyed the land and built cabins. It was also in upstate New York where John Brown hatched his first plan to emancipate slaves on a scale that had previously never been attempted.

John Brown wanted to expand the Underground Railroad

John Brown didn't let a lack of money get in the way of his efforts. His grand plan was to expand the Underground Railroad, rebranding it as the Subterranean Passway. He proposed the use of the isolated trails of the Appalachian Mountains, and a channel of forts run by armed abolitionists, to evade slave catchers in the Deep South. According to the Stuff You Missed in History Class podcast, Brown's plans for the Subterranean Passway included raiding plantations, freeing the enslaved workers, and guiding them north to freedom in Canada. His hopes were that this would degrade the value of slave property and panic would ensue, reports The Washington Post. This all hinged upon one essential element: Brown planned for these liberated men to join his armed effort to free the rest of the South.

In 1850, the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act put penalties on Americans who helped fugitives from slavery and required citizens to help in the capture of enslaved people. Incensed by these laws, John Brown established the League of Gileadites, a group that brought runaway slaves to Canada.

John Brown looks to Bleeding Kansas

In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act put the decision to outlaw slavery in states' hands. Kansas was a big question mark. Both abolitionists and pro-slavery settlers flooded the Kansas territory, hoping to sway the popular vote. Five of John Brown's sons, who had recently moved to Kansas, wrote letters to their father about their violent encounters with pro-slavery groups during the contentious Bleeding Kansas era. Inspired, Brown moved to Kansas in 1855, with a wagon full of rifles he planned to distribute to freedmen, per the Stuff You Missed in History Class podcast. John Brown's plan was to develop his own band of guerrillas to fight enslavers.

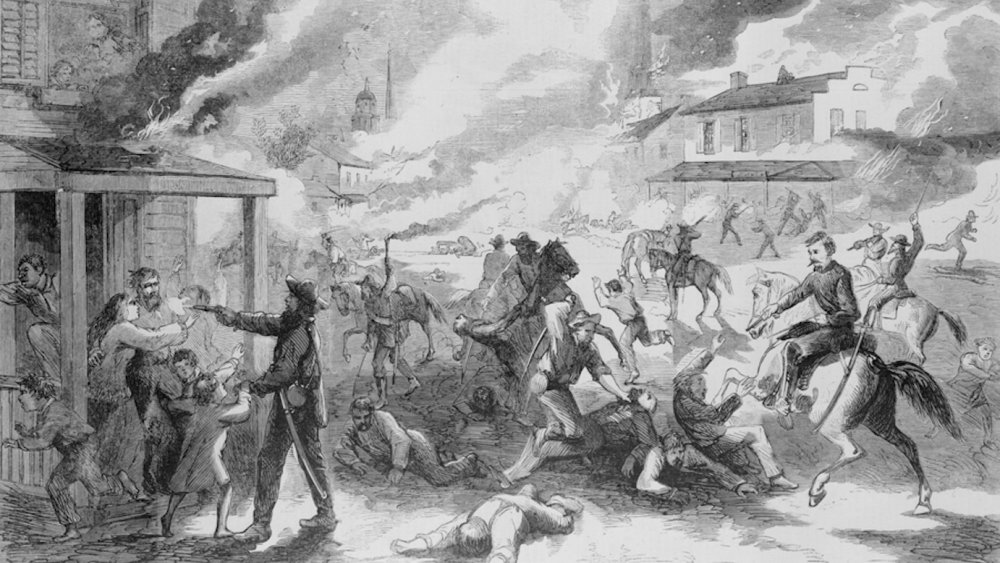

Horrifyingly, in May 1856, anti-slavery senator Charles Sumner was caned on the Senate floor. The news shook John Brown to his core, and he swore to retaliate. That opportunity came when, that same month, a pro-slavery mob attacked the town of Lawrence, Kansas — killing six people, looting, and setting the town ablaze. At Pottawatomie Creek, Brown and his men dragged five pro-slavery locals from their houses and hacked them to death with broadswords, leaving their bodies on the steps of their cabins. It became known as the Pottawatomie Massacre.

There were consequences for such gruesome murders — pro-slavery groups raided Free Staters' homes, and Brown's son Frederick was shot and killed, as told by the Smithsonian Magazine. Abolitionists of the time criticized John Brown for his vicious tactics. Brown, now in hiding, felt no remorse.

John Brown fundraises for the cause

In January 1858, John Brown left Kansas to seek out weapons, money, and men to jump-start the Subterranean Passway. Brown got involved with the Secret Six, a group of rich, white abolitionists — Gerrit Smith, Samuel Gridley Howe, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, George L. Stearns, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and Theodore Parker, per Britannica. Brown wanted to gather firearms in Virginia for a slave insurrection that would make its way south, and the Secret Six became his backers.

For a month that year, Brown lived in Frederick Douglass' attic in Rochester, New York. There, he wrote a provisional constitution for the liberated state of Virginia he hoped to build. In May, Brown called a convention in Ontario, Canada, and invited abolitionists, hoping to recruit them to his cause, as told by Stuff You Missed in History Class. A total of 46 delegates attended, the majority of them Black.

In December 1858, John Brown was back on the Western Reserve, testing his skills at shepherding freed men and women to safety. In Missouri, he freed 11 enslaved people and killed one enslaver. In a trial by fire, Brown embarked on an 82-day winter journey with these liberated slaves from Kansas all the way to the Canadian border. Brown felt it was finally time to start his slave insurrection. He asked Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, who he referred to as "General Tubman," to join him. They wisely declined. They knew the odds were against Brown.

John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

In 1859, John Brown's sights were on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, an area with about 18,000 enslaved people in a very pro-slavery state. The town had an ironworks factory, railroad, and, importantly, a federal arsenal that Brown could use in his rebellion. John Brown rented the Kennedy Farmhouse, four miles north of Harpers Ferry, where he trained 22 men — including two sons and liberated men — in combat, according to History.

On October 16, 1859, by night, Brown and his "army" swept into Harpers Ferry. They cut the telegraph lines, took control of the musket factory, and kept local enslavers as hostages. In a huge tactical error, when Brown came by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad train which was on its way to DC, he let it continue its trip after a few hours of stalling it. During the train stop, a free Black man named Hayward Shepherd, a porter, was shot when he refused orders from Brown's men, per Smithsonian Magazine. Shepherd was exactly the type of man John Brown's raid was supposed to protect.

The train alerted the federal government of the insurrection at its next stop. In town, word spread that Brown had taken over Harpers Ferry, and there was a local militia who'd surfaced to resist him. By daybreak, the swarm of self-liberated slaves that Brown had expected to join his army never came.

John Brown's rebellion fails

Without any outside aid from locals or a slave rebellion, John Brown's raid only lasted 36 hours. On the morning of the 17th, white militias had seized the railways that ran out of town, killed the free man Dangerfield Newby, and captured several of John Brown's men.

Brown and a dozen of his men holed up in the brick engine house of the railroad for safety. Brown and his followers drilled holes in the engine house's door, through which they shot and killed the mayor of Harpers Ferry, Fontaine Beckham, as reported by the Smithsonian Magazine. By nightfall, the locals were enraged, and Brown's men, many injured or dead, were at the end of the line.

President James Buchanan dispatched Marines under the command of General Robert E. Lee to quash the rebellion. The next morning, with Brown refusing to surrender, the Marines stormed what would come to be known as John Brown's Fort and captured him. In the scuffle, Brown was stuck in the abdomen by a saber but was miraculously saved when it hit his giant belt buckle and not him. In the end, John Brown's raid had killed four and wounded nine. Two of his sons had been killed, along with ten of his men. Five of Brown's army were taken prisoner. Brown, along with raiders John Anthony Copeland Jr. and Shields Green, were arrested. John Brown's holy war to end slavery was officially a failure.

John Brown is put on trial

John Brown, along with his surviving men, was charged with murder, treason against the state of Virginia, and inciting an insurrection. His trial, held in Charles Town, began on October 26, just ten days after the raid. It would be the most celebrated trial in American history at that point. Brown refused the state of Virginia's supplied lawyer, and instead, three Northern lawyers came to defend him. Because of the wounds he'd sustained at Harpers Ferry, Brown famously lay on a cot during his trial.

A guilty verdict for treason came in on November 2, with the penalty of death. John Brown spent the month between his sentencing and his execution writing letters to national newspapers and his surviving family, ensuring that his own narrative of his raid was made public. Brown was prepared to sacrifice his life for justice. He would be the first American ever hanged for treason.

In one letter written in his cell, Brown told his wife, "I love you, dear, but I can't wait to hang," according to Professor David Blight of Yale University.

The hanging of John Brown

John Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, in Charles Town, Virginia, which is now part of West Virginia. Fearing that there would be retaliation from abolitionists, Virginia governor Henry Alexander Wiser had called in 1,000 troops to line the gallows, per The Washington Post.

Among the men in attendance at John Brown's hanging were Thomas Jackson, who would later be known as Confederate general Stonewall Jackson, and eventual Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth. Jackson described Brown in a letter to his wife as dressed in an all-black suit and wearing red slippers and almost looking cheerful while ascending the scaffold.

Before he died, Brown handed a note to his jailer that said, "I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done." Those last words would prove prophetic, as the Civil War would begin in the next two years. After his death, Mary Ann Day Brown moved her husband's body to upstate New York, where he was buried.

Reactions to John Brown's raids

Some of his contemporaries and historians have illustrated John Brown as mentally unstable, a terrorist, or a traitor. In fact, it was only after Brown's execution that his fellow abolitionists began to regard him as a martyr. As recorded by the Avalon Project, Henry David Thoreau wrote in the fall of 1859 that, "He is not Old Brown any longer; he is an angel of light."

Meanwhile, John Brown had terrified enslavers in the South with the idea of future insurrections, as his Civil War dress rehearsal had awakened their worst fears, according to Stuff You Missed in History Class. After 1859, the South called for the organization of local militias in the event that a Brown-esque raid ever happened again.

The raid had also sown division among Democrats, splitting their stance on slavery in the 1860 election. This paved the way for Republican Abraham Lincoln to be elected with just 40 percent of the popular vote. After Lincoln's election, seven Southern states seceded from the Union, a major triggering event of the Civil War. Later, Frederick Douglass would say, "John Brown began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free republic," as quoted by the National Park Service. John Brown, a card-carrying rebel, had set a fire in the abolitionist movement and had leveraged his legacy into a national call to action.