The Untold Truth Of The Cheyenne Dog Soldiers

Every culture needs its heroes, and when you dig into their stories, you start to uncover some truly interesting history. The complex, fascinating tale of the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers is no exception. The Cheyenne, who've ranged from Montana to Oklahoma to Colorado, to name a few places, merged into one tribe in the early 19th century, under mounting pressure from the United States military and a growing tide of settlers. (Today, the federal government recognizes two different Nations from the larger tribe: the Southern Cheyenne and Northern Cheyenne.)

Even before the appearance of white settlers on the Great Plains, the Cheyenne people had established the tradition of military societies, which acted as community defenders, law enforcement, and even as a kind of sacred fraternity for the men of the tribe. As it turned out, a relative newcomer to these societies became one of the best-known and, for some, most feared defenders of the Cheyenne people. That would be the famous Dog Soldiers.

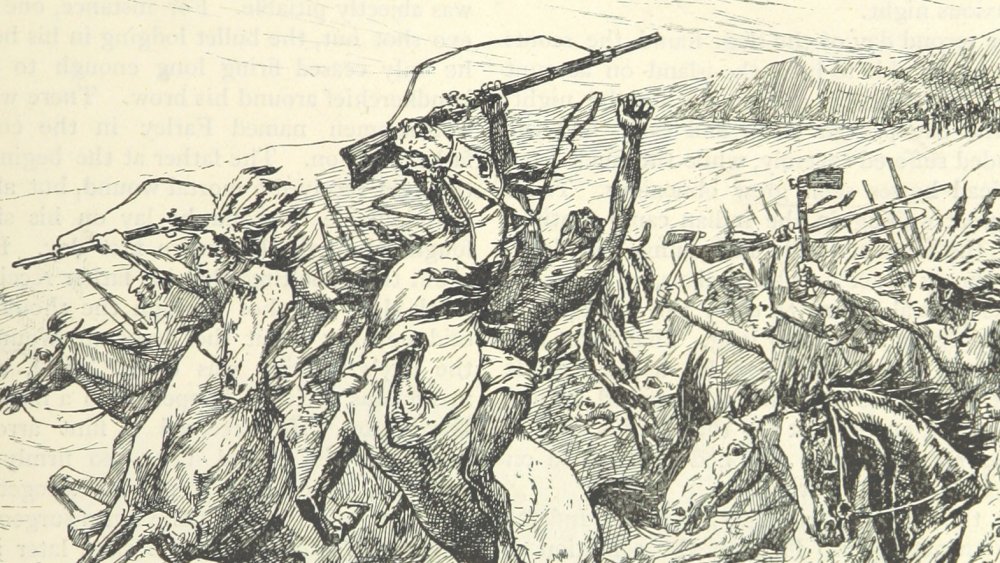

The Dog Warrior Society, also called the Dog Soldiers and Dog-Men, have made a dramatic mark on history. For some, they were frightening figures, conducting raids and tearing up peace treaties left and right. For others, the Dog Warriors were heroes defending a people in peril. Either way, the truth of their history is bound to surprise you.

The Cheyenne have a long tradition of warrior societies

Traditionally, Cheyenne tribal governance is helmed by two groups: the Council of Forty-four and a group of military societies. The Council of Forty-four consisted of elder chiefs who managed the day-to-day governance of the Cheyenne. Military societies, according to Cliff Eaglefeathers, maintained discipline within the tribe and provided military leadership.

There were a handful of military societies, some created by the legendary prophet Sweet Medicine, including the Fox Warriors Society, the Elk Warriors Society, the Shield Warriors Society, and the Bowstring Men, the names of which could vary depending on location. Other societies included the Dog Warriors, as well as the Contrary Warriors Society, who distinguished themselves by riding backwards into battle. The similarly named Contrary Society, as described by George Bird Grinnell in his book Cheyenne Indians, helped reinforce Cheyenne traditions by essentially pretending that every day was Opposite Day. And that's just a taste of the complex world of Cheyenne warrior societies.

According to legend, the Dog Warrior Society was started by actual dogs

In this origin story, collected by George A. Dorsey and published in 1905, a young man tries to start his own military society. Alas, no one wants to join. It doesn't matter that the great Prophet has given this man the inspiration — the people in one village don't know this, and they definitely don't know what to make of him. The man isn't a great warrior, nor has he established himself as someone with spiritual power. Everyone decides to laugh or simply ignores him.

The young man stays in his spot in the middle of camp, praying and singing. Eventually, the people go to sleep. The man continues, but nobody hears him — none of the humans, that is. The dogs of the settlement, meanwhile, are paying close attention. After a long night, the man gets up and walks out of camp. The dogs follow him, and when everyone stops to rest, a lodge suddenly appears around them. The dogs transform into warriors and teach the man their sacred songs and dances, just right for a new military society.

Eventually, two Cheyenne come along, wondering what happened to that strange young man and all of the dogs in their camp. They witness the scene, but when they return with some leaders, the lodge and the magical warriors disappear before their eyes. It's enough. The Cheyenne are finally persuaded that the newly established Dog Warrior Society is the real deal.

Dog Warriors could wield tremendous power at home

Dog Warriors sometimes worked as law enforcement at home, trading off these duties with other warrior societies. People acting out could face consequences from whatever group was in charge of maintaining order. Calling them "police" doesn't quite get at the heart of their role in day-to-day Cheyenne life. In Dog Soldiers, Bear Men, and Buffalo Women, Thomas E. Mails dives deeper into the subject. Dog Soldiers and other warrior groups certainly preserved order during daily life and in the midst of moving camp, which could be a complex and chaotic operation.

Dog Soldiers, along with other members of military societies, also managed tribal hunts and sacred ceremonies. With large groups of people in one place, some of whom traveled from distant settlements or other tribes, many understood the need for a recognizable force of law and order.

Dog Soldiers were also called upon to mete out punishment for a variety of crimes. And what if you committed some misdeed and were caught by the Dog Warriors? First, there was a good chance that your disciplining was going to be very public. Not only was it humiliating, but shaming a miscreant in the middle of camp served to reinforce a community's structure. If you break the rules, not only will the Dog Soldiers maybe whip you and cut up your tent, but they'll do it in front of your gossipy neighbor and that cute person you were trying to impress.

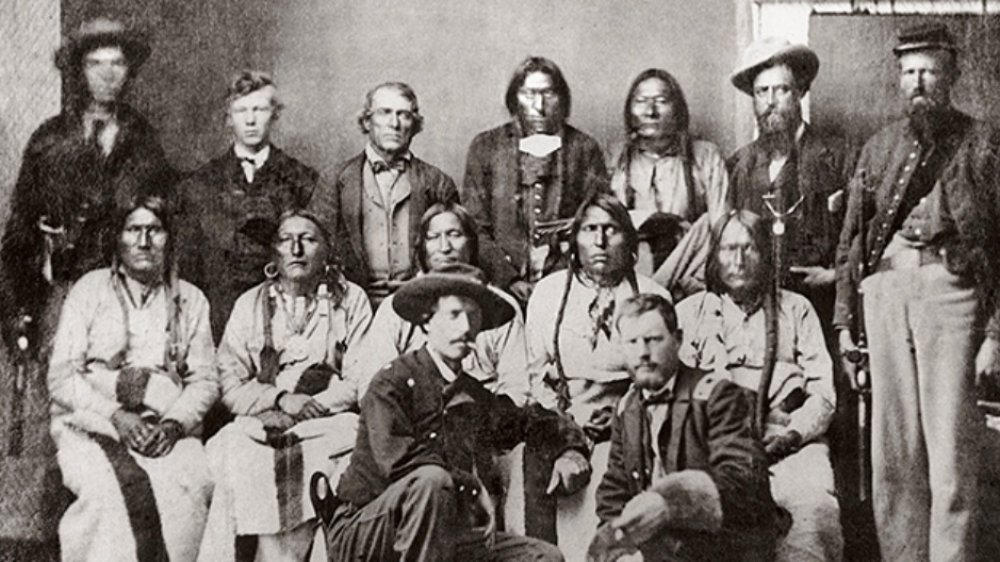

Dog Warriors also held serious political clout

Dog Soldiers didn't just have plenty of power on the home front. As time went on, they became a true political force among the Cheyenne, especially once violent clashes between Native Americans and white settlers became common. Members of the Dog Warrior Society represented a hard-line stance against the westward expansion of non-Natives into their territories. They resisted attempts to sign treaties with the US government and others, arguing that it would lead only to betrayal. Looking at the long string of such treachery against many other tribes, can you blame them?

In the 19th century, many factions of the Dog Soldiers weren't even accountable to the Council of Forty-four. According to historian John H. Moore, members of the society were governed by their own military chiefs and didn't always bother listening to other leaders. That, along with their strong sense of identity and purpose, meant that the Dog Soldiers could be one of the most cohesive groups in the entire tribe.

While some Cheyenne leaders, like Chief Black Kettle, attempted reconciliation and appeasement, the Dog Soldiers very rarely did the same. They eventually became a separatist resistance group in the 1830s, conducting raids and attacks without the consent of leaders and some tribespeople.

Not all Cheyenne thought Dog Soldiers were heroes

Though the Dog Soldiers commanded a lot of respect and even hero-worship, their legacy isn't squeaky clean. In fact, some Cheyenne came to view them as vigilantes and troublemakers. As the American Indian Wars (a collective name for many armed conflicts between settlers and Native Americans from the 1600s to the 20th century) reached the Great Plains, the growing violence only intensified their opinions.

George Bent, himself a Cheyenne and Dog Soldier, recounts one of these more troubling episodes in his memoirs. Porcupine Bear, a Dog Soldier, killed a man at an otherwise peaceful gathering in 1839. He was quickly outlawed by the tribe for his crime. Porcupine Bear didn't accept his punishment peacefully, however. He helped to turn the Dog Warrior Society into its own separate encampment, breaking from long-standing tribal custom to work under the society's own rules.

This change was dramatic. After this break, when a Dog Soldier married, he would bring his wife back to the society camp. Normally, a man would go to live with his wife's people. This helped to separate the Dog Soldiers even farther from the standard Cheyenne way of living. There's even evidence, says John H. Moore, that they went so far as to conduct their own ceremonies apart from the rest of the Cheyenne, which would have been an earthshaking break from tradition.

The Dog Soldiers became agents of righteous vengeance

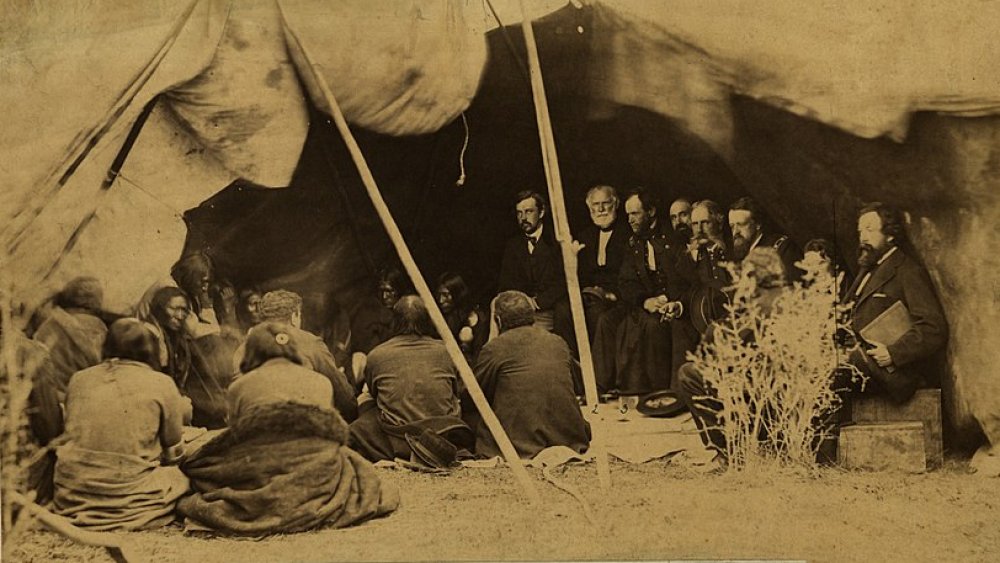

As outlined by HistoryNet, gold was discovered in the Rocky Mountains in the 1850s, leading to the Pikes Peak Gold Rush and a flood of gold-dazzled immigrants to the region. The US government pressured tribal leaders to sign a treaty reducing native territories to make way for the newcomers, but the Dog Soldiers refused to abide by the agreement.

In 1864, Chief Black Kettle led a group of Cheyenne to Big Sandy Creek in eastern Colorado. There, members of the 3rd Colorado Cavalry attacked, killing at least 150 Native people, per Smithsonian Magazine. Many of the dead were defenseless women and children. Never mind that Black Kettle had raised an American flag as a sign of peace. The Sand Creek Massacre proved to many that the Dog Soldiers had been right all along. A large number of Cheyenne decided that they simply could not trust white people anymore.

One of the best-known warriors of the Cheyenne worked with the Dog Soldiers

Roman Nose, one of the most hard-line Cheyenne, with an intimidating and sometimes flamboyant personality, often worked with the Dog Soldiers. To be fair, he was actually a member of the Elk Warrior Society, but that doesn't mean Roman Nose, who was also called Hook Nose or Woquini, didn't work with the Dog Warriors. He became especially well-known for his prowess in battle, leading to many collaborations with his fellow warriors, like the Dog Soldier leader Tall Bull. He was also deeply spiritual. Maurice Kenney, a Mohawk poet and historian, says that Roman Nose was known to spend hours in spiritual preparation, praying and readying himself for battle.

When Roman Nose died at the Battle of Beecher Island in 1868, some believed it was because he had violated a spiritual contract. His feathered war bonnet was supposed to protect him, but only if he followed strict rules. That meant Roman Nose could never shake hands, for example. Nor was he supposed to eat food that had been prepared with metal.

The morning of the battle, he realized he had eaten bread pulled from the pan with an iron fork. In Kenney's recounting, Roman Nose realized he didn't have time to fix the spiritual wound. He said, "If I go into this fight I shall certainly be killed." Indeed, he was. His death was devastating to the cause of the Dog Soldiers and the Cheyenne people.

War bonnets worn by Dog Soldiers are powerful symbols

Roman Nose wasn't the only warrior who used a war bonnet. These are more than simple hats or fodder for insensitive music festival headgear. For many, they are symbols of cultural pride and great achievement. You've got to really prove yourself to earn one of these. In many tribes, including the Cheyenne, war bonnets were granted to warriors who had proven themselves in battle. The larger or more elaborate the headdress, the bigger a deal the wearer was. Some could contain hundreds of feathers, says Dr. Leo Killsback of Arizona State University, and could incorporate culturally significant animals, such as the eagle.

Dog Soldiers were the bravest of the brave, and that meant their war bonnets could be especially elaborate. One modern recreation, worn by Jesse Lee of the Northern Cheyenne tribe, contains feathers from bald eagles, golden eagles, hawks, and vultures. Lee's bonnet, based on a 19th-century original, contains 650 feathers and took more than a year to make.

Historically, 19th-century Dog Soldiers wore dramatic upright bonnets incorporating raven or crow feathers. With smaller, bright-red plumage from other birds, these made a dramatic impact on the battlefield. As battles with US forces increased, some Dog Soldiers started wearing eagle feathers in a large, imposing arrangement. However they were arranged, these war bonnets showed that the warriors sporting them were to be seen with awe and, if you were the unlucky soul facing them, no small amount of fear.

Dog ropes held elite warriors

The most elite of the Dog Soldiers, the absolute best of the best, didn't just have war bonnets or sacred weapons — they also carried a length of rope. Now, these weren't any old pieces of rope found around camp. These tough pieces of rawhide, called dog ropes, were both a mark of honor and a promise made by the warrior to fight to the very end.

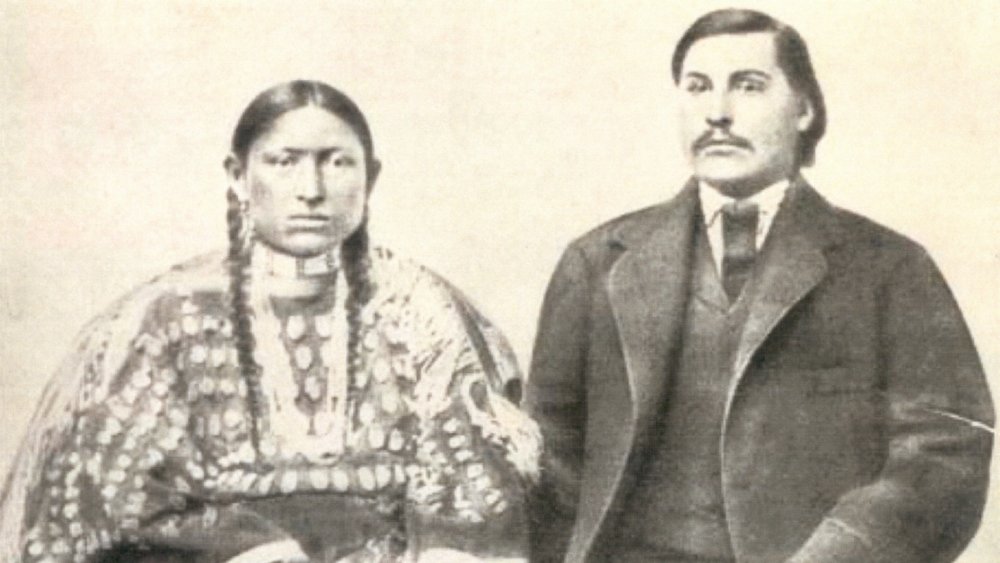

As related by George Bent (pictured above), who was a Dog Soldier during the 19th century, these ropes were carried by the bravest warriors of the society. The idea was that, during battle, someone carrying the dog rope would pin one end to the ground and fix the other end to themselves. That warrior would then fight within the small radius of the rope, showing that he was so utterly dedicated to battle that he would literally stand his ground to the death.

A Dog Soldier could only be saved from this situation by someone else. George Bird Grinnell tells a story reported by Tall Bull, a Cheyenne Dog Soldier chief. Tall Bull said that a warrior named Little Man dismounted during a retreat, pinned himself with a dog rope, and inspired his fellow warriors to stay and fight. The battle kept turning against the Dog Soldiers, however, and they were forced to continue their retreat. Little Man was only saved when another high-ranking warrior pulled up the rope and ritualistically drove him back with a whip.

Dog Soldiers led a tragic attempt to return to Cheyenne life

The Sand Creek Massacre set off another war, the Cheyenne-Arapaho War of 1864-1865. Some leaders, like the powerful Dog Warrior called Tall Bull, led their people away to the north. However, their homesickness brought them back to Colorado and Kansas in 1866. It was a harsh return. Outsiders had taken the best territory for themselves. Meanwhile, hunting and the arrival of the railroad had pushed the buffalo to near-extinction. Tall Bull, along with the other Dog Soldiers, could not stomach this.

The next steps, according to HistoryNet, were a series of negotiations that went nowhere, as far as Tall Bull was concerned. Why should they give up their hunting grounds to the whites? To what end should they restrict themselves for people who had massacred them only a few years ago? But other chiefs signed a treaty anyway, again restricting their rights. Tall Bull didn't care much for treaties. In 1868, he led warriors into the lands north of the Arkansas River to hunt in defiance of the treaty. They also raided settlements along the way.

Eventually, Tall Bull's group reached Summit Springs in July 1869, in what is now northeastern Colorado. They were pursued by US Army forces commanded by Eugene A. Carr, who attacked them. Fifty-two Cheyenne were killed, including Tall Bull himself.

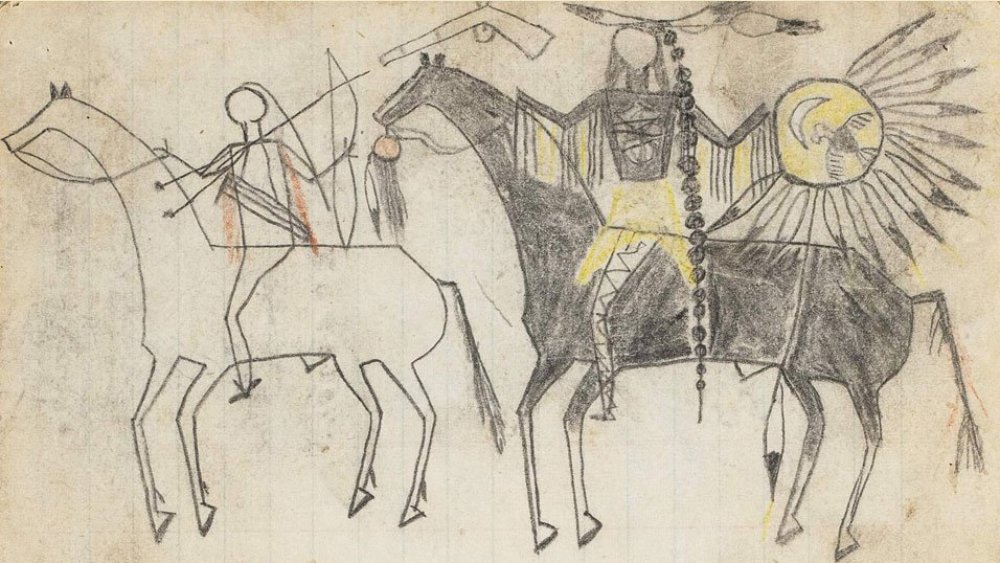

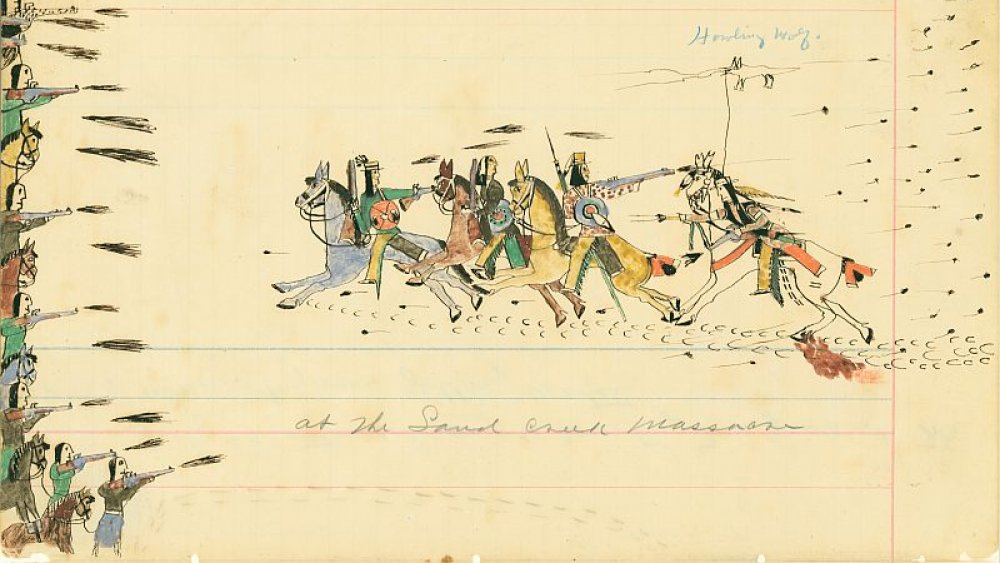

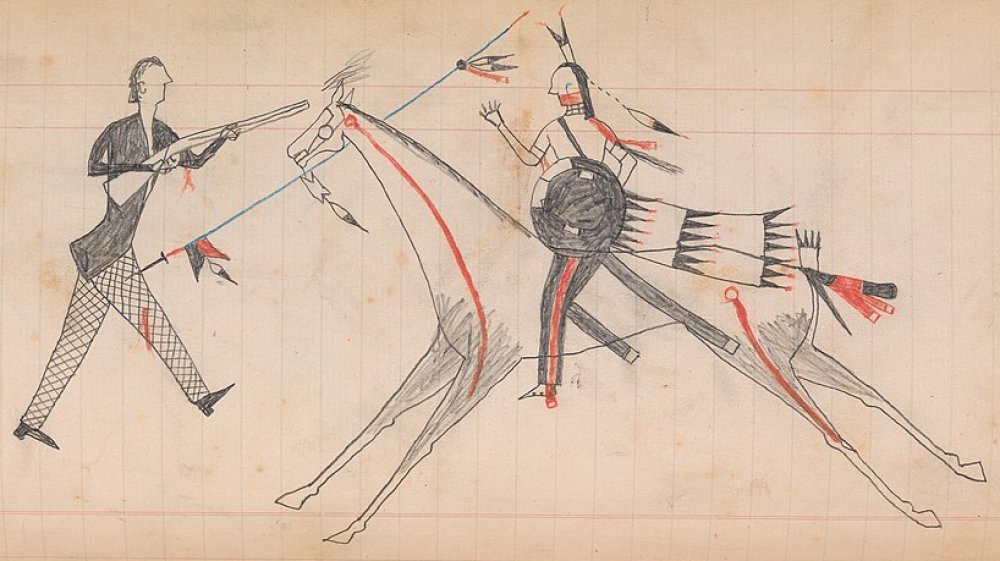

Some Dog Soldiers used art to preserve their history

Like many other Native American tribes, the Cheyenne already had a tradition of painting on hide. When notebook-like ledgers became available through trade, some continued their artwork on paper. These included the famously warlike Dog Soldiers, who drew upon their artistic skills to capture history.

These aren't some amateur scribblings, either. Sure, few, if any, of the creators here were trained in an art school, but what does that matter? These ledger books contain such a level of detail and historic information that modern-day Cheyenne can identify the people and events depicted. They are a deeply valuable record of a culture and history that has undergone dramatic change in the intervening generations.

For both the Cheyenne and those who aren't part of the tribe, the ledger books help to capture a people in the midst of sometimes shattering change. And, for what it's worth, the art created by Dog Soldiers is so important that it's now preserved in archives and museums throughout the United States.

The Dog Warrior Society still exists

After the 1869 Battle of Summit Springs (in which Tall Bull died) and many later clashes, Cheyenne military societies went underground — an understandable descision, given the way state militias and US military forces seemed bent on their destruction. Some people may have believed that the traditions of the Dog Soldiers and other military societies were gone entirely, swept under a wave of expansionist policies and cultural imperialism. But going quiet for a while did not mean the Dog Soldiers were silenced.

Indeed, few things could be further from the truth. It's an unfortunate fact that the Cheyenne, along with many other tribes, have endured generations of forced assimilation. Thankfully, though, many customs have been preserved through writing, oral tradition, art, and the brave acts of native people who resisted acculturation.

Today, members of Cheyenne bands have sparked a revival in the Dog Warrior tradition. In 1974, an Oregon reporter wrote that Frank White Buffalo Man, a grandson of Lakota chief Sitting Bull, mentioned the existence of a Sitting Bull Dog Soldier Society. More recently, Native American soldiers serving in Iraq, like Lt. Bill Cody Ayon, talked about the importance of Dog Soldier traditions to their own spiritual and cultural lives. Perhaps the greatest untold truth of the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers today is that they were never really defeated. They're still here, carrying on their traditions, holding their ground, and defending their people.