The History Of The Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party is one of the most divisive organizations to come out of 1960s and '70s radicalism. Its founders and members are either seen as murderous villains out to kill cops, or passionate, intellectual warriors, feeding children and protecting the Black community from police violence when laws and peaceful protests couldn't.

In truth, it's hard to separate fact from fiction when it comes to the Black Panthers. Partly this is because the leaders and spokespeople were very good at presenting themselves and the party in a heroic light. And partly it's thanks to the FBI wagging a years-long campaign against the Panthers, discrediting, misleading, dividing and even murdering them. While most histories of the group focus on its leaders, at its peak, the Panthers had 2,000 members, many of whom benefited in some way from the party. The real history of the Black Panthers depends on who you ask, but there's room for praise and blame.

The Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland in 1966

Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale met in 1961 as students at Merritt College in Oakland, CA. Both were involved in Black activist groups that were trying to improve the college's treatment of Black students and the community generally. By 1966, Newton and Seale had grown frustrated with the slow progress in the struggle for racial justice, which was blocked at every turn by institutions run by white people. For example, working with the North Oakland Neighborhood Service Center, Seale gathered 5,000 signatures demanding the city council set up a review board to deal with reports of police brutality. When the city ignored them, Seale and Newton decided they needed to form a new, more forceful group.

However, they also felt the riots that broke out in the wake of many acts of police brutality through 1965 and '66 weren't effective. They wanted to take the anger and energy of the young Black people involved, and channel it into what Seale described in 1988 to Blackside, Inc. as "some kind of political-electoral power movement."

On October 22, 1966, they founded the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. They got the idea for the name and the logo from a pamphlet put out by the Lowndes County Freedom Organization from Mississippi, which showed a black panther. Newton suggested it fit the movement because, he said, panthers only strike when backed into a corner — which was what the Black Panthers intended to do.

The Black Panthers formed in response to the Civil Rights Movement

When Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton met in the early '60s, the peaceful protests and demonstrations that came to be known collectively as the Civil Rights Movement were just getting started, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Black people (and some white allies) were sitting in at lunch counters and on segregated buses as part of the Freedom Rides and taking part in peaceful protests. The 1963 March on Washington and 1964 Civil Rights Act were high points that suggested sweeping change could be coming.

Except Black people around the country were still dealing with racism and racist violence every single day. Newton and Seale were voracious students of Black history. As Seale explained to Blackside, Inc. in 1988, they studied Nat Turner and other slave rebellions, and the crazy real-life story of Frederick Douglass, as well as contemporaries including Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Stokely Carmichael's Black Power. They also looked abroad to revolutionaries including Mao Zedong in China and Fidel Castro in Cuba. Years of watching peaceful protestors being beaten and arrested by police and racist whites while little changed on the ground convinced Newton and Seale to move toward Malcolm X's views. It was time for Black people to stop relying on nonviolent tactics and fight back.

The Black Panthers demanded and provided social programs

Negative depictions of the Black Panthers portray the group as a militia of violent vigilantes. But the group was clear — at least at the beginning — violence was a means to an end. Originally formed to prevent police brutality, they became famous for monitoring police while armed with guns. As law student Newton pointed out to Blackside, Inc., carrying an unconcealed weapon was legal — although History says the California legislature outlawed this in 1967 to stop the Panthers — and citizens were allowed to observe police from a distance that didn't interfere with their duties.

In 1966, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale wrote the Panthers' Ten Point Program and Platform, setting out "What We Want and What We Believe." Point Seven laid out a plan to form groups of armed Black people to protect the community from police brutality, and argued Black people should carry guns for self-defense, under the Second Amendment. Under the Panther's rules, members were banned from using weapons "unnecessarily or accidentally against anyone."

The rest of the platform addressed broader community needs. The Panthers demanded the government provide Black people with jobs, quality housing, education in Black history, and trials by their peers, meaning people with similar economic, religious, and racial backgrounds. They ran many social programs in Black communities around the country, including a free ambulance service, free shoes for people in poverty, healthcare testing, and — most famously — the Free Breakfast for Children Program.

The Black Panthers believed in political revolution

Unlike some other Black nationalist groups, the Panthers believed change should come not just from promoting Black cultural unity, but through political revolution against capitalist power structures. On June 18, 1967, the University of Washington records the Black Panthers filed to become an official political party. In 1968, the party's Minister of Information, Eldridge Cleaver, was nominated to run for President by the Peace and Freedom Party. This was symbolic: he was 33, and Presidents must be 35 or older to be elected. In a pamphlet outlining his policies, Cleaver explained his motivations, writing, "Fundamental social change will not come through the political process. But we participate in electoral politics to expose its bankruptcy and direct people to more radical forms of political struggle."

However, the Panthers did try to engage in the existing political system sometimes. In 1988, Bobby Seale pointed out that in '68 they forced the city of Berkeley, CA, to vote on a measure to replace police leaders with five commissioners who would be elected by the public. According to Seale, they lost by a single percentage point. He's also argued the Panthers encouraged Black people to vote for politicians who could serve their interests. In 1972, the party endorsed Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman to run for President — something even the Congressional Black Caucus she helped found refused to do. And Seale ran for mayor of Oakland in 1973.

Huey Newton's arrest in 1967 earned the Black Panthers publicity

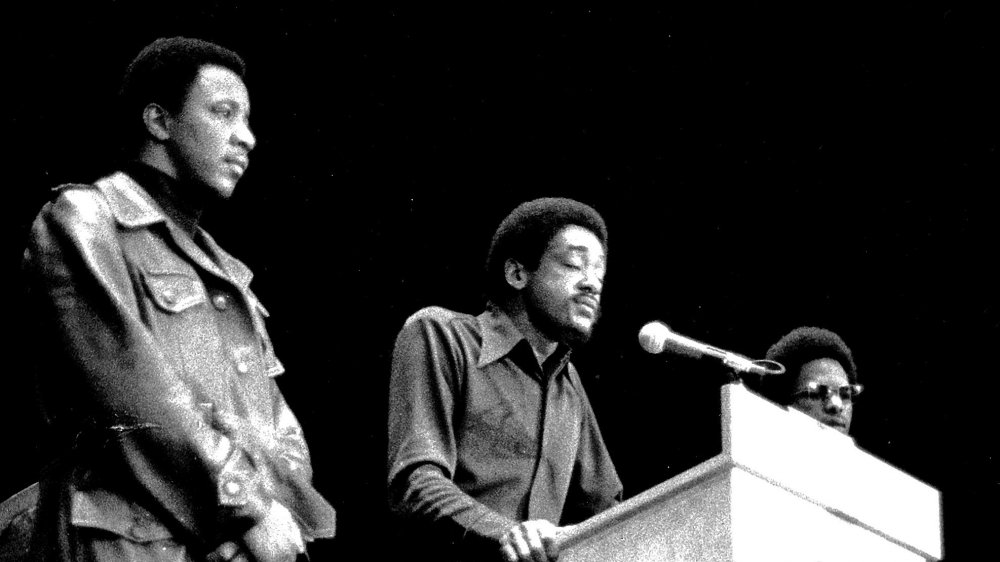

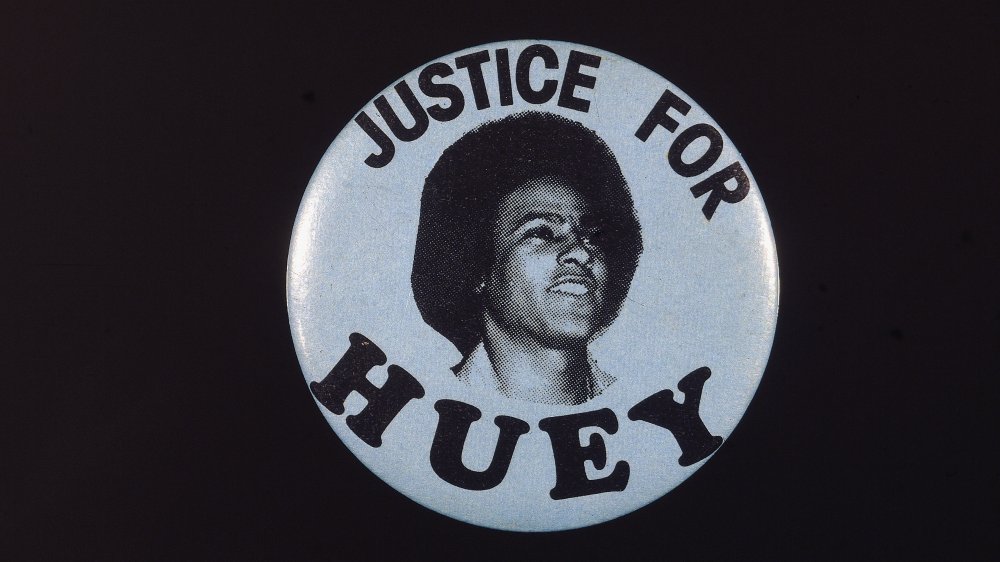

The Black Panthers first drew national press attention in April 1967, according to the University of Washington. That month, 30 armed members marched on the Sacramento state capitol building to protest the Mulford Act, and in San Francisco, 20 Panthers escorted Malcolm X's widow Betty Shabazz to the airport. But the event that won over the radical left to their cause was Huey P. Newton's arrest for shooting police officer John Frey on October 28, 1967.

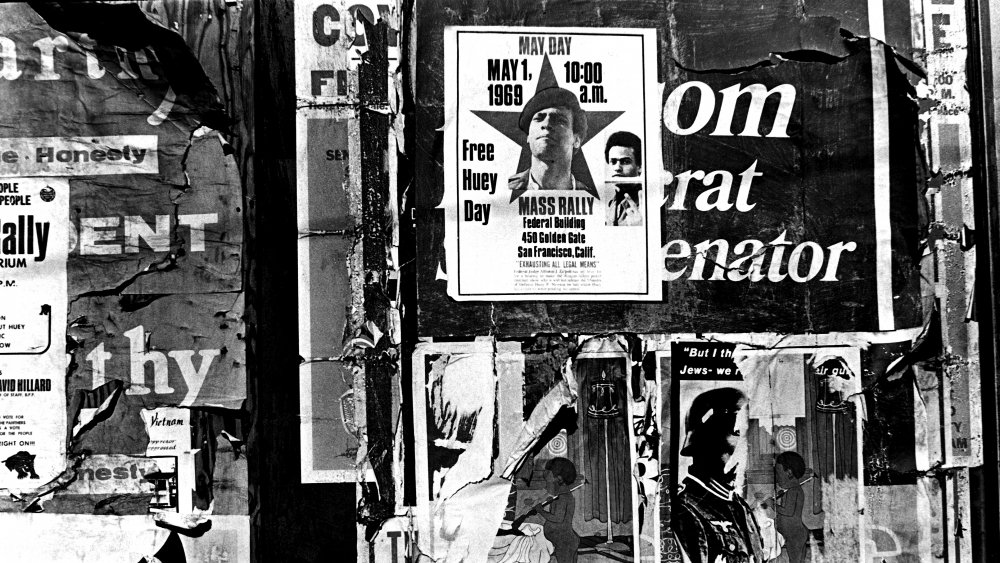

During the trial, Newton denied shooting Frey. The Panthers claimed Frey shot Newton first and he acted in self-defense. They launched a widespread Free Huey campaign, holding rallies, marches and speeches, teaming up with other Black rights groups, and raising funds for Newton's defense. Eldridge Cleaver's phrase, "If you kill Huey, the sky's the limit," became a popular cry, Seale told interviewers later.

In September 1968, Newton was found not guilty of first- or second-degree murder but was convicted for voluntary manslaughter. Some of the Panthers wanted to take to the streets, but Seale later claimed he stopped them because he knew the police were hoping for a fight. Two years later, in 1970, the charge was overturned on a legal technicality, and after two more hung juries, Newton was free.

Police targeted the Black Panthers

The police fought back against the Black Panthers. The Oakland police learned to recognize Huey P. Newton's car and regularly pulled him over: one such traffic stop preceded Frey's death. In May 1967, Newton, Bobby Seale and fellow Black Panthers Bobby Hutton and Emory Douglas were all arrested at various times for weapons charges. This became a common tactic: police would hold Panthers on a ridiculously high bail for a week or so, then release them without charges. Or the charges would be dropped in court, which still took up time and money.

According to Stanford University, in January 1968, police burst into Cleaver's home with no warrant. A month later, they forced their way into Seale's apartment and held him at gunpoint, claiming he was involved in a murder plot. On April 6, during a shootout with various Panthers, police shot and killed 17-year-old Hutton while he was surrendering. That September, off-duty cops in Brooklyn were among 150 white men who attacked a small group of Panthers. Weeks later, after Newton was convicted, two police officers fired bullets into the Black Panthers' empty Oakland headquarters.

It wasn't just the leaders who were targeted. Rolling Stone reported that by 1976, thousands of members had been arrested, many on spurious charges. For example, according to the University of Washington, in 1968, seven Panthers were arrested during a sit-in, and Stanford University says a young girl was charged with extortion for selling "Free Huey" buttons.

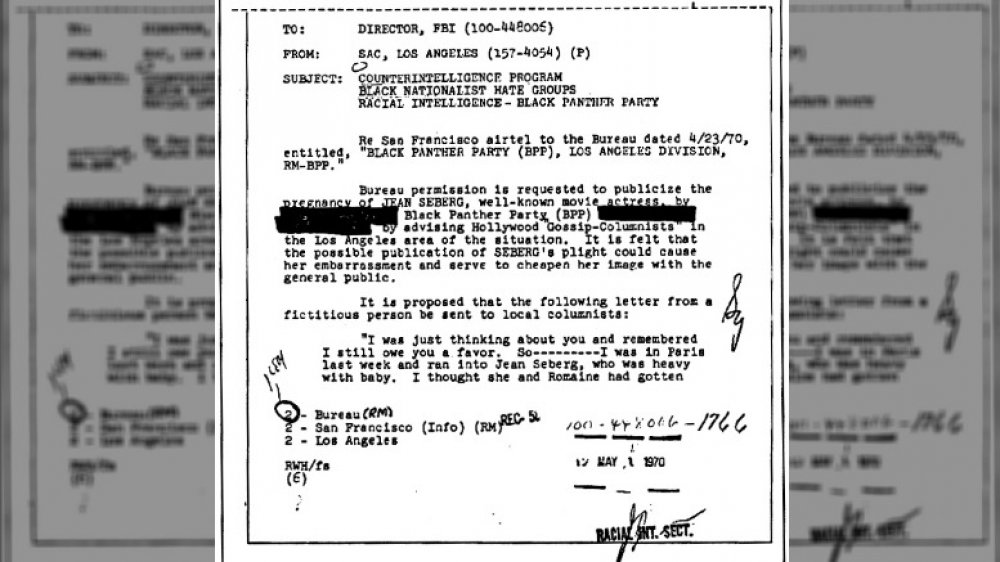

The FBI conducted a covert campaign to destroy the Panthers

The police had some help in their campaign of harassment against the Panthers. Under orders from director J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI started monitoring the party in 1967, based on COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program), a program from the 1950s formed to monitor "political radicals" within the US. Rolling Stone says Hoover created a new wing, the Racial Intelligence Section, to follow the Panthers.

In June 1969, Hoover identified the Panthers as "the greatest threat to internal security of the country." But he admitted he wasn't worried about the weapons charges the police were bringing and dropping. His concern was the Free Breakfast Program, which had started in January that year and was gaining the Panthers support from Black communities around the country. Hoover described it as "infiltration."

The FBI wasn't just watching the Panthers from the sidelines: they were stoking tensions within the group using informants and fake letters inciting violence and division. In 1969, the FBI used one such informant to get close to Fred Hampton, a young rising star in the movement and leader of the Chicago chapter. In December, the informant drugged Hampton and police raided his apartment, shooting Hampton and fellow Panther Mark Clark dead, and arresting seven other Panthers. Charges against them were dropped when it was determined that police fired 99 shots and the Panthers only two.

Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver were both charged with violent crimes

In 1969, Bobby Seale was arrested as part of the Chicago Eight, who were all charged with inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Seale had barely had any involvement with even the legitimate mass demonstrations. Blackpast says during the trial, the judge had Seale bound and gagged when he tried to defend himself. Seale's case was declared a mistrial, but the judge sentenced him to four years for contempt of court. While in prison, Seale was accused of ordering the 1969 murder of Alex Rackley, a Panther suspected of being an informant after he confessed under torture. After six months, the trial ended in a hung jury.

The Black Panthers' Minister of Information, Eldridge Cleaver rose to prominence thanks to Soul on Ice, a collection of essays he wrote while in prison for assault and rape between 1958 and 1966. On April 6, 1968, Cleaver was one of around 14 Panthers who were with Bobby Hutton during the shootout with police in which the teenager was killed. Cleaver later told PBS the Panthers started the fight, in retaliation for the death of Martin Luther King. After being arrested and bailed for his involvement, he fled to Cuba and then Algeria, where he continued to try to run the Panthers from a distance. He returned to the US in 1975, and was given probation in 1979 after pleading guilty to assault.

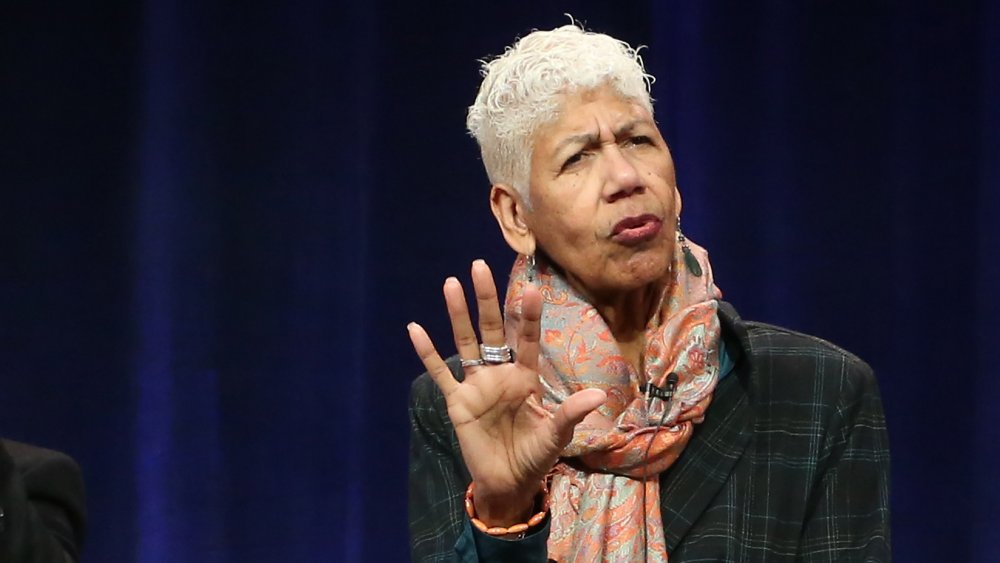

The Black Panthers had a mixed record on women's rights

Although many histories of the Black Panthers focus on the male leaders, over half their members were women. Many led local chapters, and they were often the people spearheading community programs, according to the Smithsonian. As more male leaders were arrested and jailed or fled the country, women stepped up to fill their places. The women in power sought to call out sexism they witnessed from male members. Elaine Brown even became party Chairman in 1974, but she stepped back to the status of Vice Chairman after Huey P. Newton returned to the US in 1976.

However, the Panthers' record on gender equality is more complicated than this makes it seem. One of the "8 Points of Attention" laid out by the Panthers as part of their program was "Do not take liberties with women." But several of the Panther leaders were accused of violence against women. Newton was charged with murdering a 17-year-old prostitute named Kathleen Smith, and in Soul on Ice, Eldridge Cleaver admitted to having raped an undisclosed number of Black and white women before joining the party, blaming his anger against institutionalized racism. Ericka Huggins left the party after Newton assaulted her.

Faced with choosing between the overwhelmingly white women's liberation movement or male-dominated Black nationalist groups, many Black women — who experienced racism and sexism — opted for the Black Panthers. In The Black Panther Party (reconsidered), Assata Shakur described the Panthers as, "the most progressive organization at that time."

Black Panthers were accused of cold-blooded violence

To be sure, the FBI and police concocted a lot of rumors and false charges against the Panthers. But even former supporters suspected some of their members had committed violent crimes.

In 1969, five Panthers — including Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins — were charged with the murder of member Alex Rackley, whom they suspected of being a spy. The New Haven Independent reports Rackley was tortured with boiling water for three days, then taken to a swamp and shot in the head. Huggins and Seale (pictured in a courtroom sketch) were acquitted, but Warren Kimbro, Lonnie McLucas, and George Sams Jr. were convicted.

Newton had a history of convictions for violence that preceded the Panthers. In 1964, he served a few months in prison for stabbing someone. In 1974, he was charged with shooting teenager Kathleen Smith and pistol-whipping a tailor over a disagreement over a suit. He fled the country to avoid a trial, returning in 1976. The tailor refused to testify in court, and Newton saw two hung juries, then was acquitted. In 1977, he was accused of arranging the botched murder of a witness in his trial over Smith. Later, Newton was accused of ordering the murder of Betty Van Patter, a white woman who worked as the party's accountant.

Internal divisions contributed to the Black Panthers' demise

Diehard supporters of the Panthers insist the group was driven apart by FBI tactics. And the FBI did plant false information in fake letters and through informants to make the three main leaders — Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver — believe the others were plotting against them.

For example, Rolling Stone reported that a week after Newton was released from prison in 1970, the FBI planted a document supposedly written by Panthers, implying he was nothing more than a figurehead while Cleaver was the brains. And while Cleaver was in Algiers, the FBI wrote fake letters from other Panthers and radical groups, claiming the party was falling apart under Newton.

However, the leaders played right into the FBI's hands. By 1971, the Panthers were caught in an internal war between Newton on the West Coast and Cleaver's allies on the East Coast and in Algiers. On February 26, Cleaver called into a televised interview with Newton from Algiers, demanding he expel David Hilliard, the Black Panthers' Chief of Staff. Newton refused, and a few days later expelled Cleaver from the party. Shortly after, Newton was accused of ordering the murders of Panthers in Harlem and Queens. In 1974, he expelled Seale, Hilliard, and other close friends. Former FBI agents and Black Panthers admitted to Rolling Stone in 1976 that the party might have split up even without interference from the Bureau, as Newton became increasingly erratic.

The Black Panthers officially shut down in 1982

The Black Panther Party went out with a whimper rather than a roar. Eldridge Cleaver disavowed the Panthers and became a Moonie, a Mormon, and then a Reagan-supporting Republican. The New York Times says he also struggled with an addiction to crack cocaine, and died in 1998. Huey P Newton earned a PhD in 1980, but later became addicted to drugs and alcohol. In 1989, he served a six-month prison sentence for misappropriation of funds from a community school. He was shot dead later that year, apparently in relation to drug debts. After parting with the Panthers in 1974, Bobby Seale's views became more moderate but he continued to advocate for Black communities, as well as writing books and speaking at colleges.

Beyond the leaders, the Black Panthers must deal with a mixed legacy. Many less prominent members were convicted for various crimes, including shooting police officers, during the party's extreme stages in the late '60s and early '70s. The Guardian reports around 19 are still in prison.

There is currently an organization called the New Black Panther Party, but they have been disavowed as an extremist organization by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), partly thanks to anti-Semitic views, and disowned by Seale, who described them as "nothing but some negative crap" in 2018.