The True Story Of What Happened To Rodney King

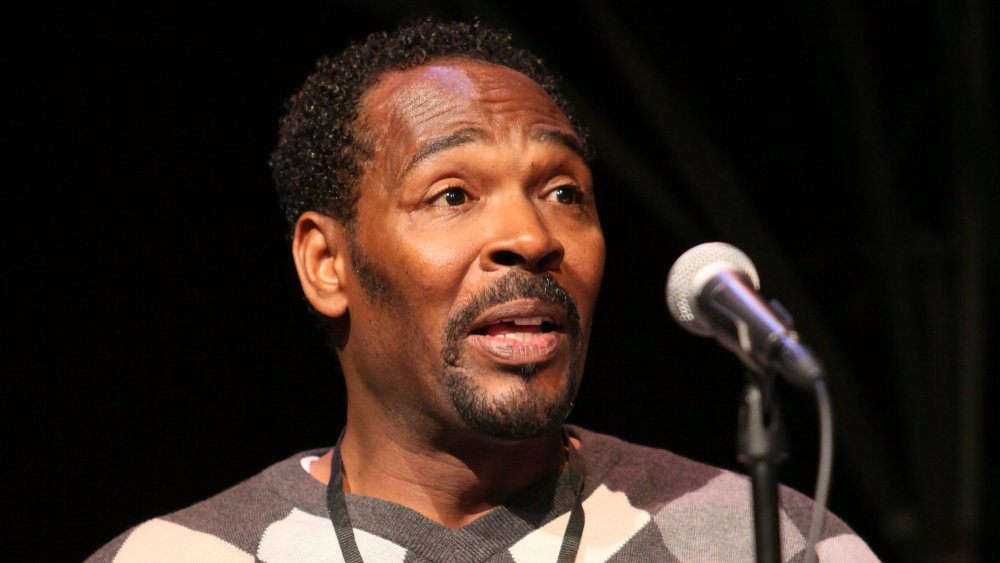

Before Eric Garner and George Floyd, there was Rodney King. While he wasn't the first Black man to be a victim of police brutality, his beating was one of the first to be captured on video and broadcast nationwide. And when, despite the vicious behavior seen in the video, the officers involved in the assault were found not guilty, their acquittal sparked what would become known as the Los Angeles Riots of 1992.

Through it all, Rodney King was just a man trying to find his way in the world. Some would see him as a hero and a martyr, while others would maintain that he was a criminal and a villain, but the police's infringement on King's rights and dignity would become a lasting symbol of the reality of police brutality. King's assault and the subsequent trials of the officers would lay bare the racism and injustice that ran through Los Angeles and its police department, becoming a catalyst for demands of police accountability.

Who was Rodney King?

Born in Sacramento, California, in 1965, Rodney King grew up mostly in Pasadena, where his family moved soon after his birth. In his memoir The Riot Within, King recounts growing up with an alcoholic and abusive father and the struggles that produced at a young age. His father worked two jobs, and when King was eight years old, his dad decided that he would take his children along to his night custodial job. While his father would drink and listen to country music, King and his brother would buffer the floors until 2:00 AM, barely having a chance to get some sleep before having to wake up for school in the morning. As a result, King was frequently tired and unresponsive in class, which led the school to place him in a disabled learning class.

According to The Guardian, King started drinking at an early age and had various encounters with law enforcement before the notorious 1991 assault. In November 1989, he was arrested for assault and robbery and sentenced to two years in prison. After one year, King was released on parole and a found part-time job as a construction worker at the LA Dodgers' baseball stadium.

Events leading up to Rodney King's assault

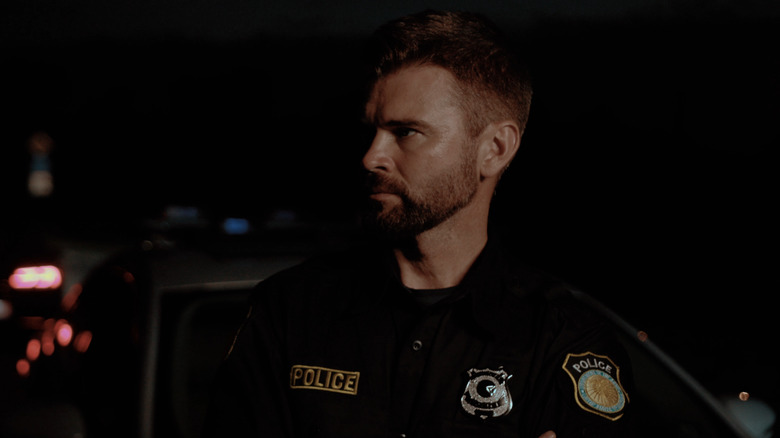

According to Famous Trials, in the early hours of March 3, 1991, King and two friends, "Pooh" Allen and Freddie Helms, decided to go out after watching a basketball game. They'd all been drinking, and King was behind the wheel when two California Highway Patrol officers, Tim and Melanie Singer, spotted them speeding down the 210 freeway. King reportedly led them on a high-speed chase, running a red light and nearly causing an accident before finally stopping near Hansen Dam Park. By the time King stopped, Officers Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, Theodore Briseno, Rolando Solano, and Sergeant Stacy Koon had all arrived at the scene.

The police ordered everyone out of the car, but only Allen and Helms complied. King stayed in the vehicle until police yelled at him a second time to get out. According to Melanie Singer's testimony, when King did get out of the car, he displayed erratic behavior, such as waving at the police helicopter and waving his butt at the officers.

The officers would write in their report that due to his behavior, they suspected King of being under the influence of PCP, which was believed by the police to give people under its influence superhuman strength. This belief is actually a crude regurgitation of a myth started by Dr. Hamilton Wright in 1910, which claimed that Black people experienced superhuman strength under the influence of cocaine. In the end, King's toxicology report was negative for PCP.

The police beating of Rodney King

After finally catching King's vehicle, police proceeded with the arrest. As King exited the vehicle, Officer Koon claimed that he had "felt threatened, but felt enough confidence in his officers to take care of the situation." Police alleged that King resisted lying down on the ground, and after Koon yelled for officers to stand back, he fired his Taser twice at King. Koon claimed that King was unfazed by either Taser strike, with Officer Solano further corroborating that King proceeded to lunge at Koon. In his report, Officer Powell wrote that King was only temporarily halted by the Taser before appearing to attack again.

The police then proceeded to beat King with their batons, claiming that King continued to resist and struggle as the officers used swarm techniques to subdue him. The officers noted the use of force and batons in their reports, concluding that it had been justified, given King's aggressive nature. Koon also wrote in his sergeant's log that King was "oblivious to pain." This notation also bears racist undertones, echoing the work of Dr. Samuel Cartwright, who, in 1851, wrote of enslaved people being "insensible to pain when subjected to punishment."

After the beating of Rodney King

After the beating, the police called an ambulance, and King was taken to Pacifica Hospital with officers riding along. Doctors gave King several stitches, noting in his medical records that he suffered from a broken cheekbone and broken right ankle. Afterward, King was moved to a jail ward at County-USC Medical Center, where he was booked for evading and resisting arrest.

Alcohol and drug tests would later show that King had been over the legal limit while driving and had a trace amount of marijuana in his system, but not much else was noted by doctors at the time. Martha Esparza, a nurse who worked at the jail ward, would later testify that King was "calm and cooperative," while the officers who brought him in were bragging and joking about the number of times King had been hit.

After prosecutors were unable to find sufficient evidence to prosecute, King was released after having been held for four days. In the claim King later filed with the city, he reported having suffered multiple skull fractures, broken bones and teeth, kidney damage, brain damage, as well as physical and emotional trauma.

George Holliday's video of the beating

The police chase after King had ended in front of an apartment building, waking one of the tenants with the sound of helicopters at 1:00 AM. Witnessing the scene from his balcony, Holliday decided to start recording. According to El País, Holliday was about 40 meters away from the scene, and his camera was able to capture the sounds and images of a beating that would last eight minutes. For most of the video, King would be on the ground.

The next day, Holliday called the Foothill Station with the intention of giving the police the video of the incident. But when he talked with the desk officer about having witnessed an incident of police brutality and asked about the state of the driver, he was met with disinterest and dismissal. In light of the LAPD's attitude, Holliday decided to take his video to the media, and on March 4, the videotape was aired for the first time on Cable News Network KTLA. The next day, the FBI opened an investigation, and the head of the LAPD promised an inquiry.

This recording would go down in infamy for its exposure of police brutality, along with police corruption, as the video contradicted the LAPD's report. Compared to the seven blows noted in the police report, Holliday's video shows more than 50 baton blows.

The LAPD report

The LAPD report would later become an issue of controversy due to its misrepresentation of the events of King's arrest. While the reports that were filed mentioned the beating and the use of batons, various inconsistencies arose when compared with Holliday's video.

Powell's report would leave out several important details, such as the presence of Allen and Helms in the car and civilian witnesses at the scene. He would also write that King was only struck about seven times. However, according to Human Rights Watch, in reporting the incident on his car radio, Powell claimed, "I haven't beaten anyone this bad in a long time."

In Koon's report as well, the use of force was downplayed and justified. Both Koon and Powell would later be charged with filing false police reports, since neither of their accounts mentioned the blows to King's head, nor the fact that he was on the ground for most of the time while he was being beaten.

The trial of the officers

Without Holliday's video, the officers might never have been charged for the assault. But once the video was in the hands of the media, it couldn't be swept under the rug. By March 6, King was released from jail without charges due to a lack of evidence against him, and by March 8, the DA sought to indict the officers involved in the assault.

King would testify that he wasn't sure if the officers had yelled racial slurs at him, since there was little he could focus on at the time of the beating. However, police phone messages would show that in response to an incident immediately before the King beating, officers described it to the command center as "right out of Gorillas in the Mist," a statement which the prosecutor would bring up to demonstrate a pattern of racist behavior.

Four officers — Koon, Powell, Wind, and Briseno — would be indicted for various charges of assault, excessive force, and falsification of police reports. The 17 other LAPD officers who were there and did nothing to prevent the beating faced no repercussions. The trial would begin about a year after the incident, on March 5, 1992, and after seven days of deliberations, on April 29, the jury came up with a not guilty verdict for the four officers in regards to their use of excessive force. According to NPR, the unrest started less than three hours after the verdicts were reported.

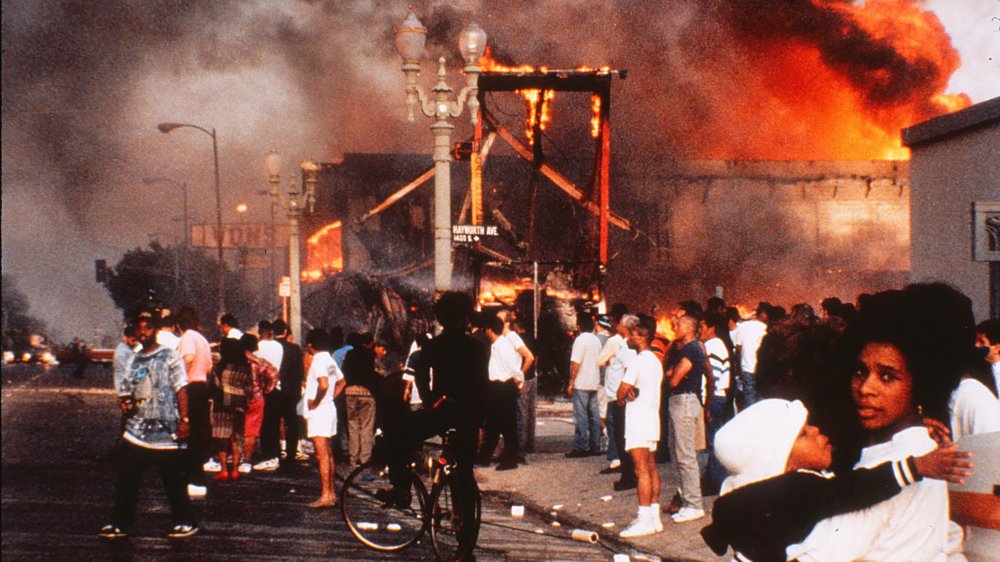

Raging at injustice

The acquittals were considered a gross miscarriage of justice, with the mayor of Los Angeles, Tom Bradley, calling the verdict "senseless." Residents of Los Angeles erupted into a fury that had been mounting over the years, especially towards the police, who were seen as an oppressive rather than protective force. Residents of the city would riot for six days, during which time there was also widespread looting, a tactic that has been used often to protest the valuation of property over human life.

According to CNN, the riots began in South Central Los Angeles, at the intersection of Florence and Normandie. A state of emergency was quickly declared by Mayor Bradley, and Governor Pete Wilson called in the National Guard, although LAPD Chief Darryl Gates reportedly told police officers to retreat and offer no helpful response to the violence and looting.

Citywide curfews were instated from April 30 to May 4 in an attempt to subdue the disturbances. Marines, Army soldiers, and the National Guard were also brought in to monitor the streets. The riots resulted in more than 2,000 injuries, 50 deaths, and 6,000 arrests. Rodney King himself would speak out publicly on the third day of the riots, proclaiming what would become an iconic statement: "People, I just want to say, you know, can we all get along? Can we get along?"

Indicted once more

During the riots, President George Bush had promised that charges would once more be brought against the officers. On August 4, 1992, three months after the Los Angeles riots ended, a federal grand jury once more indicted officers Koon, Powell, Wind, and Briseno, this time for violating King's civil rights. In June, Police Chief Gates had resigned, having come under public pressure following the assault and his inaction during the riots.

By bringing charges of civil violations against the officers, the Bush administration attempted to quell demands for more expansive investigations into police reform, refocusing the charge against the particular officers rather than the system as a whole. This time, in April 1993, a jury found Koon and Powell guilty, with Wind and Briseno being acquitted once more.

Koon and Powell were sentenced to 30 months in a federal correctional camp. While the government thought that the sentence wasn't severe enough and appealed, according to the Los Angeles Times, after a series of back and forths, the original sentence of 30 months was upheld. By December 1995, both Koon and Powell had been released from prison.

Rodney King's settlement with the city

During this time, Rodney King was involved in his own litigious activities with the city. In his memoir (via NPR), King describes how Mayor Bradley had offered him college tuition in lieu of going to trial, an offer that came out to about $200,000. Rejecting that offer considering that he'd almost lost his life, King sued the city for $56 million, amounting to approximately $1 million for every strike by the officers.

The city of Los Angeles eventually reached a settlement with King, paying him $3.8 million for pain, suffering, and medical bills. With the settlement, King was able to buy a home for his mother, as well as one for himself. However, most of the money would end up going to lawyers' fees and the music label King tried to start.

Alta-Pazz, according to King, was meant to be a label that brought opportunities to young Black and Hispanic people who were struggling with employment. But despite the fact that everyone at the label was well-intentioned, few had knowledge of the music industry, and the label soon went under.

Rodney King's struggles with addiction

After the beating, King continued to struggle with alcoholism and had several more run-ins with police over the years. In 1993, King entered an alcohol rehab program after crashing his car in downtown Los Angeles, although according to the Associated Press, in 1995, he was once again arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol.

King was arrested once more in 1999 for a domestic altercation and sentenced to 90 days in jail in addition to being required to attend a batterer's treatment program. In 2001, after an arrest for indecent exposure while under the influence, King was once again ordered to attend a rehab program, though this program would also prove unsuccessful.

After several more incidents with drinking and domestic disputes, King would go on to appear on two seasons of Celebrity Rehab in his attempts to get his addiction under control. His work with Dr. Drew Pinsky would continue in Sober House, and during one episode, King revisited the place of the 1991 assault. According to NPR, despite his best efforts, King said the battle for sobriety was continuous.

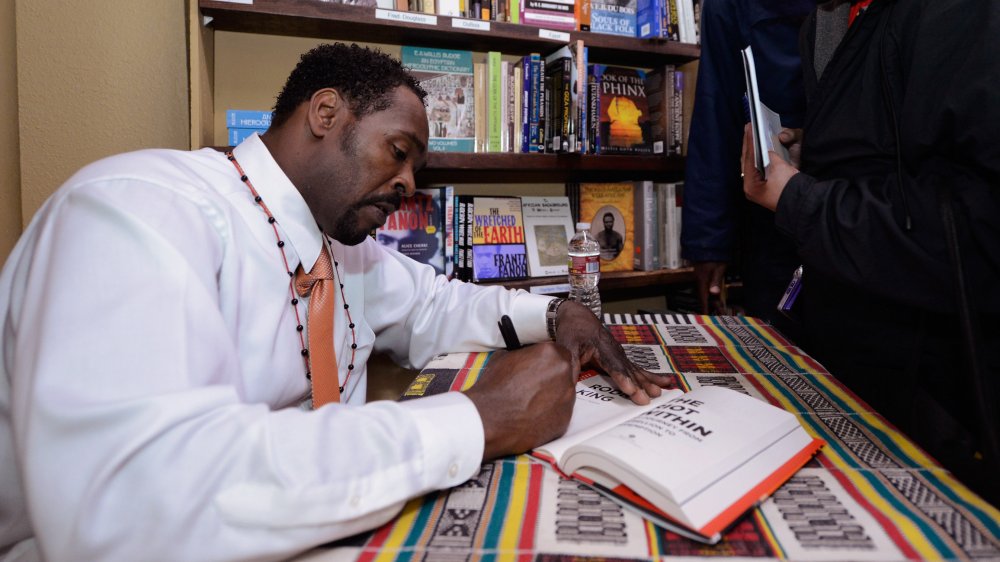

Rodney King's memoir and his final days

After repeatedly spending time in and out of rehab, King would continue to waver between sobriety and relapse. During this time, with the help of a ghostwriter, King wrote his memoir, The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption. The book traces his own life and the impact his case had on civil rights in the United States and offers his own testimony on learning how to forgive through time. The role that the assault played in King's life and the role it played in the civil rights movement were inextricable, but King's book gave him a chance to separate "Rodney King the man" from "Rodney King the movement."

However, just a few months after the book came out, King was found dead in his pool at age 47 by his fiancée Cynthia Kelly. According to CNN, King's death was ruled to be an accident, caused by alcohol as well as a variety of drugs in his system.

Despite his untimely death, King's daughter Lora King continues to fight for his legacy. In 2019, she launched the "I am a King" scholarship, which works toward offering financial support to Black fathers in order to relieve financial insecurity and provide opportunities for the entire family.