The Legend Of Mermaids Explained

While some legendary creatures are highly regional and completely unknown outside of their place of origin, mermaids are almost universal in their spread across the globe. Pretty much anywhere you turn, cultures have a story about a beautiful woman (or sometimes, an equally attractive man) with a fish tail, who spends her free time charming sailors with her ridiculously good looks or magical singing voice. Sometimes the lucky mariners get to kiss the girl, and sometimes the poor unfortunate souls get dragged to the briny deep, never to be seen again. So maybe think twice if you encounter one.

Just in case you ever do sail into one of these mysterious maids from under the sea, here are some fast and fishy facts about the alluring yet possibly deadly daughters of Triton. Read on if you would like to make these stories part of your world. This is the legend of mermaids explained.

Atargatis, the first mermaid

Mermaids are not just a type of folkloric creature with variants all over the world: stories of mysterious, seductive, and often dangerous maids of the sea are also pretty much as old as written history. As Wired explains, the earliest known mermaid-like figure from mythology is the Syrian goddess Atargatis, who was a goddess of fertility but also more generally a protector responsible for the well-being of her people. The historian Diodorus Siculus, who calls Atargatis by the name Derceto, tells the story that the goddess fell in love with a handsome human youth and gave birth to a daughter by him. In her shame, she killed the young man, set the baby out to die by exposure, and threw herself into a lake. Rather than dying, she was transformed into a being with a human head and a fish's body. She was thus worshiped by the Syrians in this form, and her majestic temple included a pond full of sacred fish, and her worship included a proscription against eating fish. Don't worry about the baby, by the way: some doves saved her, and she grew up to become the legendary queen Semiramis.

While Atargatis might have been the first mermaid, she was preceded by a merman in the form of Ea, the Babylonian sea god who was also a dude on top and fish on bottom.

The 50 daughters of Nereus

Greek mythology never misses a chance to have naked young women running around, so it probably won't surprise you that mermaids can be found in the tales of the Greeks and Romans. Specifically, the Greek mermaids were sea nymphs known as Nereids, which as Theoi Greek Mythology explains means they were the daughters of the shape-shifting sea god Nereus. They were protectors of sailors and fishermen, while also representing various aspects of the sea's rich treasures, such as sea foam, waves, and, like, cool rocks. There were 50 Nereids, but the only two who get any real attention by name are Thetis, who was Achilles's mom and the unofficial leader of the Nereids, and Amphitrite, who was Poseidon's queen and the mother of their merman son, Triton, who could raise and lower flood waters by blowing his conch shell horn. The Nereids were not consistently portrayed as mermaids (nothing in myth is all the way consistent), but sometimes just hot girls riding dolphins or sea horses.

Meanwhile, the Roman historian Pliny the Elder describes Nereids as half-woman, half-fish, though the human half was "still rough all over with scales," claiming that a number of their bodies had been found littered on the seashore. He likewise describes a merman who, rather than being the helper described in myth, would climb onto the sides of ships and cause them to sink.

Sirens: neither fish nor fowl

Mermaids have something of a dual personality throughout world folklore: they can be beautiful maidens who help the sailors they fall in love with, or they can be deceptively seductive monsters looking to take unwary mariners down to Davy Jones. Part of that latter depiction might come from the conflation of mermaids with the Sirens, which according to Theoi Greek Mythology were the sea nymph monsters who used their hypnotic singing voices to lure sailors into crashing their ship on the rocks. Jason and the Argonauts encountered them on their search for the Golden Fleece, and Odysseus was only able to hear their voices and survive by tying himself to the mast of his ship while all his men plugged their ears. But as the Audubon Society explains, the Sirens were originally depicted as bird women, not fish women. The Sirens depicted in classical pottery and sculpture have human heads and the bodies of birds, creatures generally seen as omens and protectors of secret knowledge.

Probably due to their association with the sea and conflation with similar seductive singing water women like the Lorelei, the dangerous beauty of the Rhine River, the Sirens eventually morphed into mermaids and are often popularly portrayed that way today. The conception of the Sirens as mermaids is so strong that the modern Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese (among others) word for "mermaid" is sirena.

Melusine, the two-tailed freshwater mermaid

A specific mermaid legend that is especially well-known in northern and western France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands, is the tale of Melusine, a water spirit found in sacred springs, rivers, or other freshwater sources. According to Ancient Origins, Melusine is the eldest daughter of a Crusader king and a woman that the king did not know was a fairy. He encounters a beautiful woman in the woods, and she agrees to marry him if he never looks in on her when she bathes her triplet daughters. The king breaks this promise, and the fairy mother flees with her daughters to the magic island of Avalon. When the eldest triplet, Melusine, grows up, she seeks revenge against her father by imprisoning him in a mountain. When her mother learns of what Melusine has done, she curses her to take the form of a fish (or sometimes serpent) from the waist down every Saturday. In a variant of the story, it is Melusine herself who is found by a promise-keeping king in the woods, but the end plays out about the same.

Melusine is typically depicted as a mermaid with two fish tails rather than one, and a number of royal houses claimed to be descended from her, including the French House of Lusignan (saying that Melusine derived from Mère Lusine, "mother of the Lusignans"). More likely, however, you would recognize Melusine from the Starbucks logo.

Not surprisingly, the Russian mermaid is grim and deadly

The Slavic version of the mermaid, called the rusalka (or rusalki in the plural), is a little different from others in that they have legs instead of fish bodies, but they have a lot in common with mermaids, Nereids, and Sirens in that they are female water spirits who lure men in with their charms. As Ancient Origins explains, however, their motivation for such beguiling is definitely sinister. While the original folkloric form of the rusalka was as a benevolent fertility spirit who provided freshwater moisture to forest and crops to help them grow, by the 19th century, they had become the restless spirits of the unquiet dead. Specifically, rusalki were the spirits of women who had died violent deaths by drowning, either by murder or by suicide after being jilted by a lover.

Rusalki lurk around lakes, rivers, swamps, and ponds, seeking revenge on the humanity that betrayed them by lunging out of the water to grab human men and drag them down to share their watery fate. Rusalki are quite a contrast to the beautiful mermaids of other cultures, as they are said to have pale skin, green hair, and pupil-less eyes that flash green with rage. A tragic opera based on the story of the rusalka was composed by Antonin Dvorak in 1901–titled, naturally, Rusalka– and is probably the most famous Czech opera ever staged. Try to think of a more popular Czech opera. You probably can't.

One Abdullah, Two Abdullahs, Red Abdullah, Blue Abdullah

While most versions of One Thousand and One Nights don't literally have 1,001 stories in them, most editions of this collection of Middle Eastern and Indian tales contain hundreds of stories with fantastical themes, so it probably won't surprise you that there are some mermaid stories in there. One such story is the tale known as "Abdullah the Fisherman and Abdullah the Merman," which tells of a fisherman named Abdullah who has a large family and a sudden case of bad luck when it comes to catching fish. On his last attempt to catch something before giving up, he reels in a merman, whose name is coincidentally also Abdullah. The two obviously become best friends.

They become business partners and Land Abdullah sells underwater jewels provided to him by Water Abdullah, which first gets him arrested but ultimately allows him to marry a princess (because that always has to happen in fairy tales, right?). Water Abdullah gives Land Abdullah a magic ointment that lets him breathe underwater to visit the land of the merfolk, which is full of naked people eating raw fish, engaging in some light communism, and partying at funerals. Land Abdullah gets wigged out by that last part, which offends Water Abdullah, and so he is cast out of the sea kingdom and never sees his best merdude again, though he's still a prince, so things didn't turn out too bad.

The tragic Chinese shark person

The folklore of the various East Asian countries also has various approaches to the legend of the mermaid. China, for example, tells of the jiāorén ("shark people"), which despite their frightening name are actually more associated with producing precious jewels and cloth than anything you might see in a Sharknado film. According to The World of Chinese, jiāorén look more or less like Western mermaids, but they spend their days weaving a marvelous legendary cloth known as Dragon Yarn. Dragon Yarn is said to be white as snow and unable to become wet, even when soaked in water. The jiāorén reportedly sell their yarn to mortals at markets that are magically disguised to seem like normal markets. Additionally, should they ever cry, the tears of the jiāorén turn into beautiful pearls. Because the lore around them centers so much on their magical tears, jiāorén are often tragic figures in Chinese literature.

In contrast, the Japanese mermaid known as the ningyo ("fish person") is a hideous, otherworldly creature with fish-like features, bony fingers, and long, sharp claws. Legend says that anyone who eats the flesh of the ningyo will gain eternal life and youth. Few are willing to risk such a hunt, however, as the ningyo can place a powerful curse on those who attempt to capture them, including destroying entire towns with earthquakes or tidal waves.

Oh, the huge manatee

One of the most famous real-life sightings of mermaids occurred on January 9, 1493, when genocidal maniac Christopher Columbus and his crew of racist murderers spied three mermaids in the Caribbean on their way to plunder the island now known as Hispaniola. According to History, six months after setting out from Spain in his incorrect attempt to find India, Columbus recorded seeing three mermaids in the sea, but claimed that they were "not half as beautiful as they are painted." The reason for this may be that what he was actually seeing were either manatees, dugongs, or the now-extinct Steller's sea cows. These adorable creatures have round faces and human-like eyes, and might resemble hot fish ladies if you are the kind of person who would confuse Haiti for India.

Sea mammals and other large marine creatures are thought to be behind many sightings of alleged humanoid sea creatures like mermaids. Renaissance Europe believed that life under the sea perfectly mirrored life on the land, so besides sea cows and dogfish and such, they also imagined a full undersea clergy, like sea bishops and sea monks. These creatures are said to have actually washed up on shores in northern Europe, and while their actual identity has never been definitively determined, theories include that they were walruses, hooded seals, anglerfish, giant squids, or angel sharks.

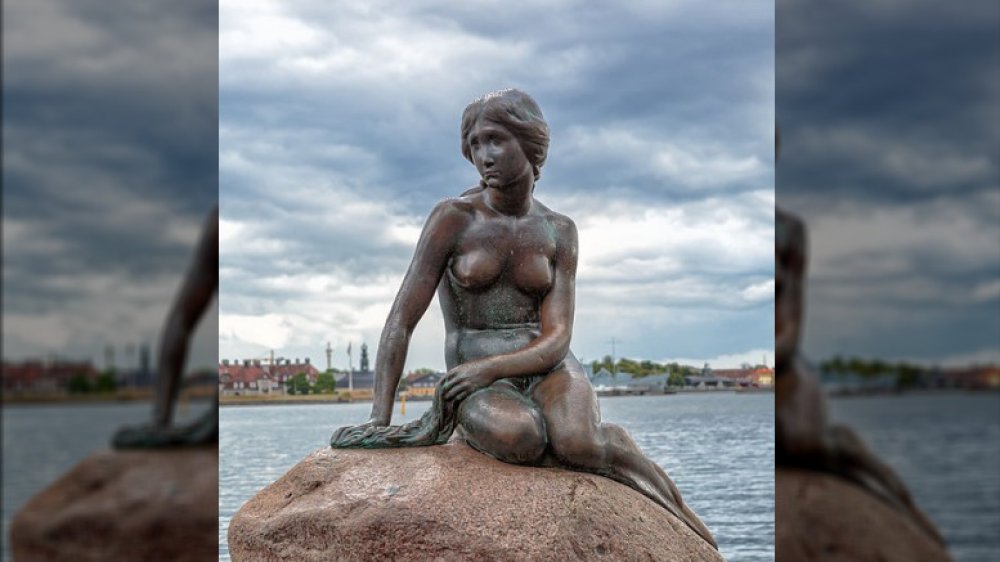

The original Little Mermaid had no soul

Almost certainly the most famous fairy tale about mermaids is Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Mermaid," one of the most beloved stories by arguably the most beloved author of literary fairy tales. This particular story grew from being a source of local pride in Denmark to a full-on worldwide phenomenon thanks to the 1989 Disney film of the same name. Suffice it to say, however, that–as Bustle records–the Disney version diverges from the original story in a number of ways. For example, when the animated Ariel (nameless in the fairy tale) gets human legs, the movie fails to mention that walking feels like being stabbed with knives. Also, the fairy tale mermaid does not get the prince, is forced to dance at his wedding to someone else, and can only escape a horrible fate if she stabs the prince to death in his marriage bed with a–what do you call it?–knife.

But perhaps the most striking aspect of mermaid lore focused on in Andersen's story is the idea that mermaids don't have souls, and rather than go to heaven when they die, they dissolve into sea foam. They can, however, gain a soul, by marrying a human nobleman, which is at least as much of the little mermaid's motivation as love. Andersen took this aspect of mermaid ontology from a mermaid-like legendary creature known as an Undine.

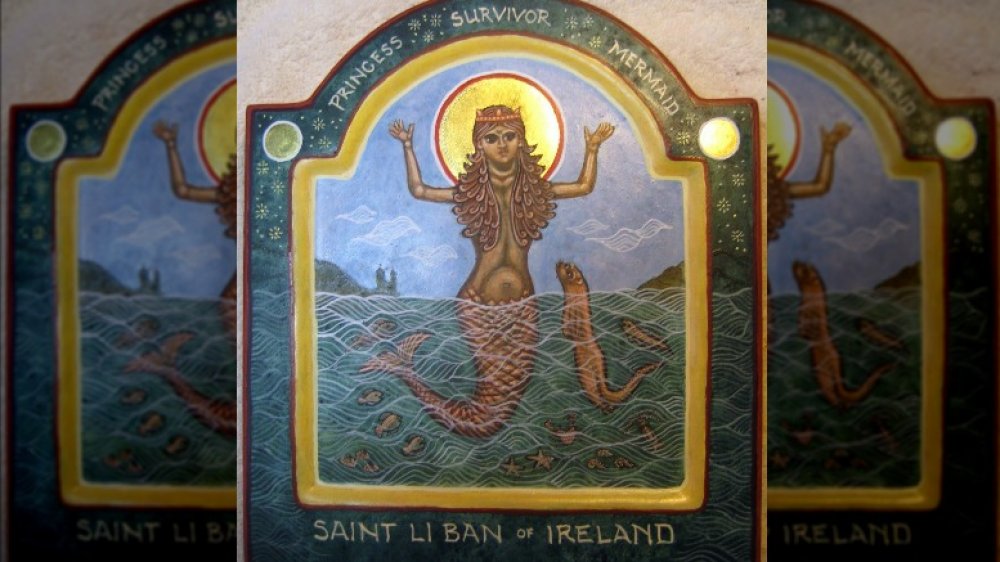

Li Ban, the Mermaid Saint

If you know anything about folk Catholicism–not the official stuff that the church publicly espouses, but the stuff that common people believe–you know that they'll make a saint out of just about anything. There's a saint that's a werewolf, one that's a dog, and one that's a woman with an impressively full beard. As such, it may not surprise you to learn that Ireland has a mermaid saint, known as either Li Ban or Muirgen at various points in her life.

As Irish Central explains, Li Ban was the daughter of the King of Ulster, and she and her dog were the only survivors when his lands and palace were flooded by a sudden upwelling of water that formed Lough Neagh, managing to live alone in an underwater chamber for a year. During that time, she prayed to the Irish goddess Danu that she might be turned into a salmon and swim away. Well, she got half her wish, getting turned into a half-salmon mermaid (her dog became an otter, don't worry). The two swam out to the open sea and drifted for 300 years, until Christianity came to Ireland. At this point she was caught in fishing nets and brought ashore, at which point she was baptized and christened Muirgen ("sea-born"). She died soon after, but she received the reward of Heaven she was promised, becoming eternally the Mermaid Saint.

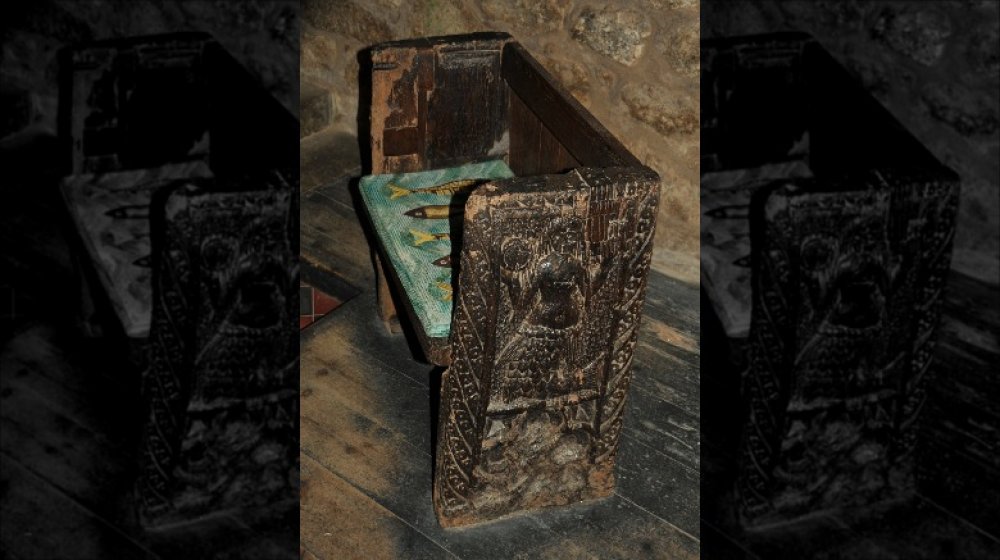

The mermaid chair of Zennor

One of the more interesting mermaid-related artifacts out there is an unusual chair inside a church dedicated to St. Senara in the Cornish village of Zennor. As Atlas Obscura describes, the object in question is an ornate bench with fish painted on the seat and a beautiful mermaid admiring herself in a mirror carved on the side. This chair with a mermaid on it is known, fittingly, as the Mermaid Chair.

According to legend, a beautiful but mysterious woman used to attend services at this church. No one knew who she was, but the villagers noted her beautiful looks and singing voice, as well as the fact that she never seemed to age. Eventually, she fell in love with a young man named Matthew Trewella, and the youth follows her home, never to be seen again. Later, a ship at anchor was surprised when a mermaid appeared in the cove and asked them to move their anchor, as it was blocking the entrance to her house. Recognizing her as the mysterious young woman from the church, the sailors knew that Matthew had been taken by the daughter of the sea king. The Mermaid Chair, which dates back to the 15th century, is said to be either the very bench where the mermaid would sit and sing in church, or else a warning to young men to be careful who they follow home.

PT Barnum's ugly mermaid

For those of you reading this who were around in the 1840s, your best shot at seeing a mermaid would have been at one of many exhibitions put on by P.T. Barnum, the most trustworthy man ever to grace the earth. As Live Science explains, his famous exhibit, shown in New York, Boston, and London, was known as the Feejee Mermaid (also sometimes spelled Fiji or Fejee). Unlike the classically beautiful mermaid of legend and lore, Barnum's Feejee mermaid was notoriously hideous. Barnum himself described it as "an ugly dried-up, black-looking diminutive specimen, about 3 feet long. Its mouth was open, its tail turned over, and its arms thrown up, giving it the appearance of having died in great agony."

The reason for that was that this "mermaid" was almost certainly made from the top half of an orangutan sewn to the bottom half of a salmon. The Feejee mermaid was only one such hoax mermaid put together by Japanese fishermen that made its way to the West via Dutch traders, but the success of this particular chimerical hoax shows Barnum's talent as, like, some kind of pretty good showman. Unfortunately, the Feejee mermaid disappeared from a museum in Boston in 1859, and its whereabouts are currently unknown.