What The Final 12 Months Of Layne Staley's Life Was Like

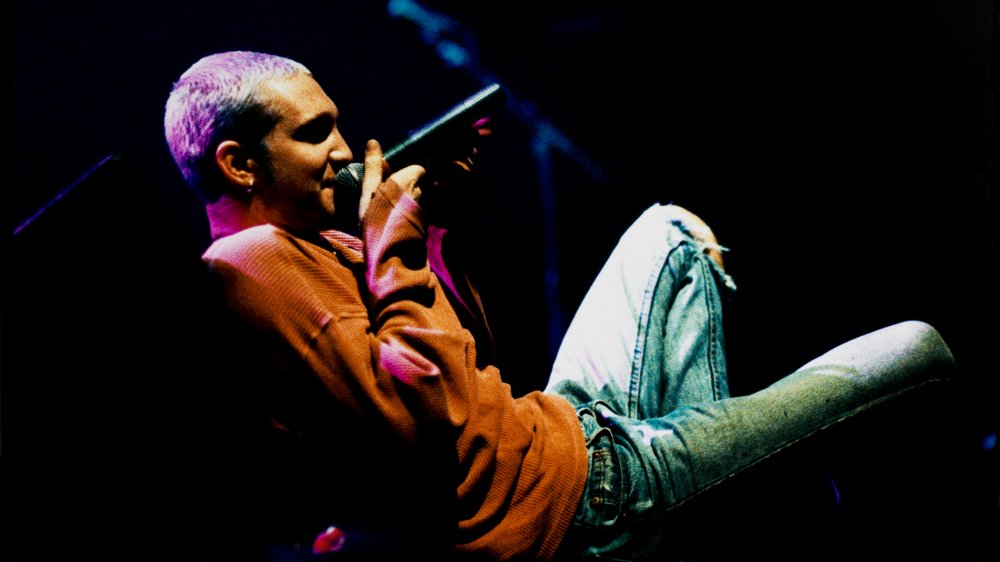

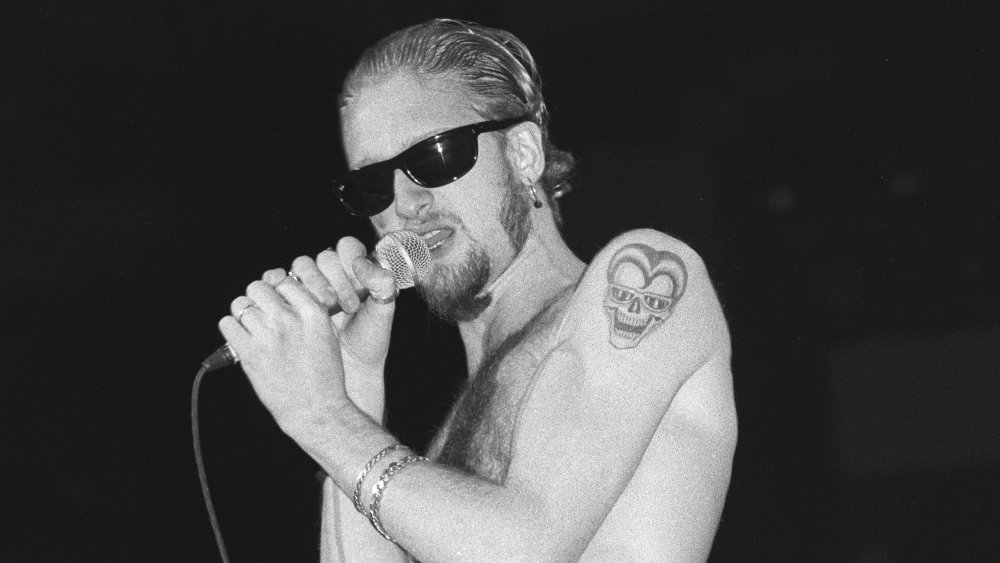

For many fans, Alice in Chains epitomized the musical movement we now call "grunge." Merging the hard-hitting riffs of California's metal scene with the vulnerability and depression of the Pacific Northwest, the Seattle-based quartet created music that was heartfelt without being angsty and tough without being hilariously macho. And while much of Alice in Chains' appeal can be credited to the swampy, languid riffs of guitarist Jerry Cantrell, even more of the band's uniquely powerful sound is owed to the vocals of original lead singer Layne Staley. Layne's full-throated crowing and pained howls expressed a pained sense of humanity that many young listeners — embracing the jarring nuances of the '90s after emerging from the pastel shallowness of the '80s — felt down to their bones.

But while many singers attempted to sound more broken than the rest during grunge's heyday, Staley could unfortunately back up the emotion behind his music. By the time he passed away on August 5, 2002, the singer was physically and emotionally crippled by his addiction to heroin, as well as his use of other drugs. And while he will be forever remembered for his long and storied musical career, the last year of Layne's life depicts him as a very different person, whose traumas and issues with addiction had fundamentally changed the musician so many people knew and loved.

Layne Staley literally locked himself away from the world

According to Guitar World, in 1997, Layne Staley, using the entity the Larusta Trust (Layne often used the fake name John Larusta in his business dealings, perhaps as a reference to the Alice in Chains' classic "Rooster"), purchased an apartment in Seattle's bustling University District. This would be the singer's home for the next five years leading up to his death. Yet, for the last year of his life, almost no one visited Staley in this apartment, and he rarely left. For the most part, Layne kept an incredibly private and insular life in the year leading up to his death, to the point where the few times people did see him, it was a notable event that they remembered well.

According to a Facebook memorial post by early collaborator Tim Branom that was reprinted in Alternative Nation, "In the end, almost no one could contact Layne. He wouldn't answer the door or take calls. He lived in a condo right smack in front of everyone, in the University District. He weighed 80-some pounds and his health was deteriorating. There were reports that he would go to Toys R Us to buy games and return home, but always by himself."

Gaming had become a way for Layne Staley to lose himself

It was well-known that Layne Staley was a lover of video games and would often disappear to play games throughout Alice in Chains' recording process. In Greg Prato's book Grunge Is Dead, his mother Nancy described him as a "video game freak," while Tad Doyle of the seminal Seattle band Tad describes how Alice in Chains would have his band on their tour bus "playing video games and listening to music."

However, like many of the things that seemed to make him happy, video games became an escape for Staley, a way to put his mind to something that didn't wear too hard on his emotions. In a Rolling Stone profile of the band, while Alice in Chains are playing WhirlyBall, a combination of lacrosse, basketball, and bumper cars that only rock stars can ever dream of enjoying, "Staley [bows] out to play video games on his portable Sega system."

Layne Staley knew he was dying months before his death

There's a trope that rock stars overindulging in bad behavior and harmful drugs "think they'll live forever." But by the end of his life, Layne Staley was not only aware that his drug use had screwed up his whole world, but that he wouldn't be around much longer.

In his last interview months before his death with Argentinean journalist Adriana Rubio, Staley admitted that he knew he was on his way out. "I know I'm dying," he said in a portion of the interview reprinted by MTV. "I'm not doing well. Don't try to talk about this to my sister Liz. She will know it sooner or later. [...] I know I'm near death. I did crack and heroin for years. I never wanted to end my life this way. I know I have no chance. It's too late."

Perhaps the most painful thing about this is that Layne's sense of hopelessness drove him to isolate even further and push away even those who loved him. "I know I did my best or what I thought would be right," he said. "I changed my number. I don't wanna see people anymore and it's nobody's business but mine."

Layne Staley didn't want anyone else using heroin

Many outsiders looking in at grunge claimed that the movement glamorized drug use, promoting the concept of art and addiction being intertwined via their lyrics and the growing concept of "heroin chic" that was popular in '90s fashion. But Layne Staley's final interview reveals that he was no longer using heroin for pleasure, but simply because he was so addicted to it that he couldn't possibly stop.

"This f*cking drug use is like the insulin a diabetic needs to survive," said Staley in a portion of the interview published by Blabbermouth. "I'm not using drugs to get high like many people think."

Because of this, Staley was disgusted by heroin's effect on his life — and that he didn't want Alice in Chains' fans to think it was cool. "I never wanted [the public's] thumbs' up about this f*cking drug use," he said. A moment before, Staley had revealed: "My liver is not functioning and I'm throwing up all the time and sh*tting my pants. The pain is more than you can handle. It's the worst pain in the world. Dope sick hurts the entire body."

Layne Staley's mother was working with a rehab clinic when he died

Perhaps closest to Layne Staley in the 12 months before his death was his mother, Nancy McCallum, who had always been there for her son and helped him seek out treatment for his addiction. Nancy was even working in a treatment center the day Staley died — and it was her intervention that led the police to find the singer's body.

According to an interview she did with The Seattle Times, Nancy was working the front desk of a rehab clinic on the day that Layne passed away. She was even planning to meet with one of the supervisors there to map out a new line of treatment for her son. Then, she received a call from his accountant saying that Staley had taken out a large sum of money weeks ago and that no one had heard from him since. Nancy rushed to his apartment, and when Staley didn't answer, she contacted the police.

In many ways, Nancy is still haunted by her son's addiction — addicts and fans send her letters all the time — but she also sees Layne's lyrics on the subject as helpful and prophetic. "That's what his music was about," she said. "The life of an addict. [...] He chose to write about it and sing about it and perform about it. It was a warning."

Layne Staley was in poor physical shape, but his mood was good

As Layne Staley's health deteriorated, he became less interested in being social or recording with his band. That said, the people who saw him deep into his addiction claimed that while Staley looked terrible physically, he was often the same smiling, lighthearted guy they remember.

According to an interview with Staley's stepfather Jim Elmer in David De Sola's book Alice in Chains: The Untold Story, Layne seemed to be in high spirits even toward the end of his life: "He was smiling, he was talkative, so there's a good sign that either he was doing better or he was trying to do better, that there's a more hopeful thing as compared to 'We're going to lose him in two days' or something like that."

Jeff Gilbert, an editor at Seattle music magazine the Rocker, said that when Layne approached him on the street toward the end of his life, he looked bad physically but seemed aware emotionally. "He looked like an eighty-year-old version of himself, and it was frightening. [...] He still managed to smile. Every so often, you'd see that little glimmer."

The last time Layne Staley's family saw him, he was in good spirits

As Layne Staley became more and more engulfed by his addiction to heroin, many of those around him began to see him as a withdrawn and tragic figure, but the last time his family saw him alive was actually in a rather sweet and good-humored capacity.

In a profile on Staley from The Seattle Times, his mother Nancy said that her final memory of her son was him holding his nephew while visiting his family in February 2002. "I saw Layne on Thanksgiving of '01 and again just around Valentine's Day when he came to see his sister's new baby. The last time I saw Layne — and the last picture we have of him — is holding baby Oscar."

Nancy makes a specific point of mentioning that although her son had become withdrawn from the public, he was available for those close to him. "He was never far from the love of his family and friends — who filled his answering machine and mailbox with messages and letters. [...] Just because he was isolated doesn't mean we didn't have sweet moments with him."

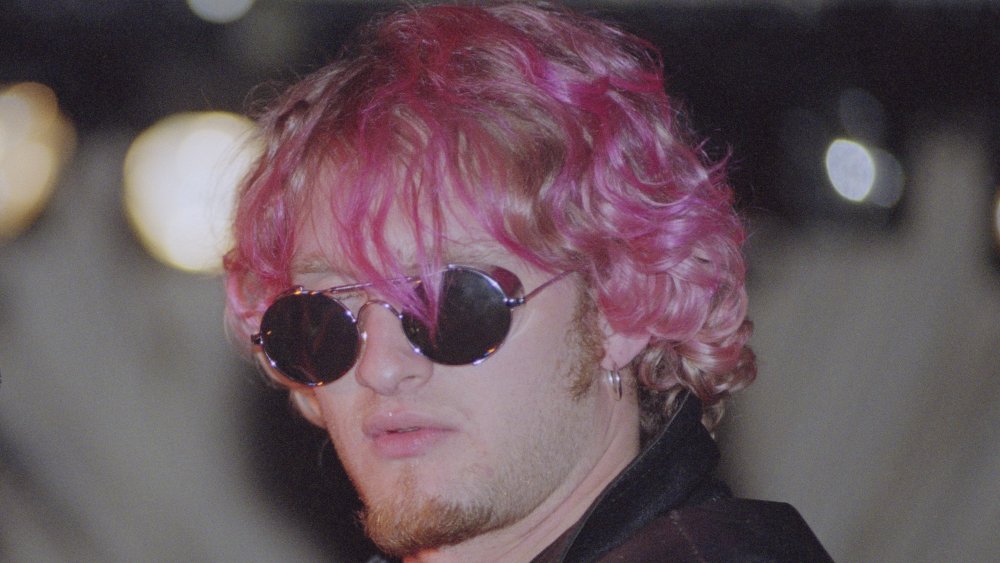

Layne Staley intended to record a song with Taproot the year of his death

These days, many believe that grunge killed heavy metal outright, the former's ferocious honesty instantly silencing the latter's superficial love of girls, drugs, and soft-boil satanism. But plenty of grunge's big acts loved metal's hard-hitting underground, few more so than Alice in Chains, whose syrupy riffs and outright aggression earned them an opening spot on 1991's Clash Of The Titans tour alongside Slayer, Megadeth, and Anthrax.

As such, it might not surprise some to learn that Layne Staley was actually planning to record guest vocals on a song with alternative metallers Taproot for their 2002 album Welcome. The band's unique sound — staccato rhythms, throbbing groove riffs, and alternating guttural and harmonized clean vocals — made the album pretty perfect for a Layne Staley guest spot, and according to Alice in Chains: The Untold Story, Staley was enthusiastic about recording the vocals, though he asked that producer Toby Wright come alone because he "wasn't looking or feeling great, and he didn't want to be seen."

Sadly, Staley's vocals never got recorded, though he was interested in the project right up until his death. According to a statement by former Taproot drummer Jarrod Montague republished by THEPRP, Layne's mother told the band that when he died, he had Taproot's demo of their track in his CD player.

Layne Staley claimed to have been visited by the ghost of his girlfriend

In 1988, Layne Staley met Demri Lara Parrot, a model who would eventually become a grunge icon. Demri had a look that seemed to define the musical era, beautiful in a small-town way with her bright eyes, round cheeks, and curly hair. According to Alice in Chains: The Untold Story, it was love at first sight. The two soon became engaged but eventually broke up around 1994. By then, Demri had also become addicted to heroin. On October 29, 1996, she passed away due to inflammation of the heart caused by a previous overdose, according to Find A Grave.

When Alice in Chains' first bassist Mike Starr was hanging out with Staley the day before his death — the last time, as far as Staley's friends and family could tell, that anyone saw the singer alive — Layne revealed that he'd seen Demri recently in his apartment. The two were watching the show Crossing Over, on which a medium claimed to speak to audience members' dead relatives, when Staley said, "Demri was here last night. I don't give a f*ck if you f*cking believe me or not, dude. I'm telling you: Demri was here last night."

According to The Untold Story, Demri's mother Kathleen Austin has heard Mike Starr's story and believes her daughter visited Staley "to be there with Layne as he's doing his transition."

Layne Staley refused medical attention the day before he died

Original Alice in Chains bassist Mike Starr spent the day before Layne Staley's death — Starr's birthday, in fact — hanging out with the singer at his University District apartment. The interaction was mixed: According to David de Sola's book, Layne was in a sour mood and got into an argument with Mike over his use of benzodiazepine.

Perhaps the most tragic part of this was that the bassist, worried by Staley's appearance, tried to call 911 for his friend — but the singer declined. Speaking during a February 2010 episode of Loveline, Mike said, "I was with him all that day on my birthday trying to keep him alive. I even asked him if I could call 911, you know, and he said that if I did, he'd never talk to me again. Of course I didn't know he was going to die, or I would've called 911 anyways. I'd much rather have him alive and not talking to me than to have lost such a great human being [...] a great friend. And just a great person. What a great person he was."

Layne Staley's body wasn't found for weeks after his death

Layne Staley's official date of death was declared April 5, 2002. However, his body wasn't discovered until April 20, two weeks after the singer had passed away from an overdose.

According to Seattle Weekly, police were forced to break down Staley's door after his mother had called them to his University District apartment. The scene they found there was a harrowing one: brown heroin stains leading from the bathroom to the living room, stashes of cocaine and crack pipes around the house, the TV on and flickering. Staley's body was sitting upright on his couch. According to Ultimate Classic Rock, his 6'1" body weighed only 86 pounds, and in one of his hands was a syringe loaded with heroin.

A toxicology report done during Staley's autopsy found that he had morphine, codeine, and cocaine in his bloodstream. His death was ruled accidental.

Layne Staley's tragic death has left a legacy of recovery and hope

Layne Staley was the ultimate example of a rock 'n' roll tragedy — a star whose incredible talent and creativity was cut short by an addiction that eventually grew out of his control. But somehow, out of Layne's story grew a bloom of hope for artists in the same position.

According to The Seattle Times, shortly after Staley's death, his mother Nancy began receiving donations and letters from fans all around the world struggling with addiction. (She's quick to note, "I don't have any magic answers. I just try to console people.") From that arose the Layne Staley Memorial Fund, a way to help those dealing with addiction to pay for treatment services. According to Therapeutic Health Services, which runs the organization, Nancy sees the fund as a means of "partnering with Layne on the next step in his work. He was very honest with people about the effects of drug use, urging them not to follow in his footsteps. Those were the messages in his songs, endearing him to his fans."