The Untold Truth Of Ida B. Wells

There are two types of people: those that complain about injustice, and those that do something about it. Ida B. Wells was the latter.

She's an often-overlooking figure in the fight for civil rights, even though her life story sounds like something out of a movie that took a lot of artistic license. It's full of resistance and courage, of death threats and violence, of family, community, and struggle.

The years after the Civil War were full of turmoil: Wells' parents were active in the Reconstruction movement, establishing aid societies and colleges. That put her on the front lines, and by the 1890s, she had embarked on a cause of her own: an anti-lynching crusade. It was a horrible time. According to Ferris State University, an estimated 4,000 people were lynched between 1882 and 1962. Sometimes, lynchings were community events, complete with speeches, torture, even picnics organized by those who came to watch. A newspaper in Mississippi once called these events "Negro barbecues," and that's the world Ida B. Wells waded into, armed with a pistol and a desire to see justice served.

Ida B. Wells had a difficult young life

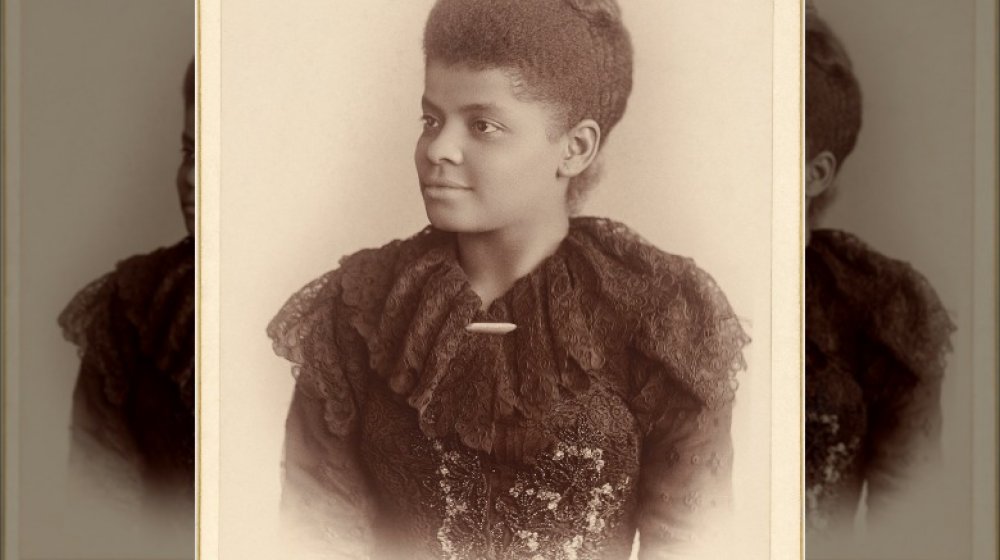

Ida B. Wells was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1862 — the Civil War was still going on, and she was still a slave. After the war, her parents set a very clear example for her. They were active in the Republican Party of the Reconstruction era as well as the Freedmen's Aid Society, and her father was one of the founders of Rust College. (Wells herself attended the college, too... albeit, briefly: the National Women's History Museum says she was expelled for starting an argument with the president of the university.)

Tragedy — the first of many — struck in 1878. Ida B. Wells was visiting her grandmother when a yellow fever outbreak swept through her hometown, killing both of her parents and her baby brother. As the oldest, Wells suddenly found herself in charge of her siblings. That's when the 16-year-old Wells convinced a school administrator she was actually 18, and got a job as a teacher to provide for her siblings (via the National Park Service). Four years later, she and her family moved to Memphis, Tennessee to be closer to an aunt. She would continue her education there, and that's also where she took a stand that would change the course of her life.

When Ida B. Wells was told to give up her seat...

It was September 1883. Ida B. Wells was 20-years-old, and she was on a train from Memphis to Woodstock, Tennessee. She was reading a newspaper, and when the conductor asked for her ticket, he also told her she needed to move to the front car — the car reserved for Black passengers. She refused, telling him she had a very good reason for being exactly where she was — she had paid for a ticket, this was the ladies' car, and she was a lady. The forward car, on the other hand, was where people could smoke, and she didn't want to be around that. That didn't go over well with the conductor.

She later wrote in her autobiography (via Timeline): "[He] tried to drag me out of the seat, but the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand. I had braced my feet against the seat in front and was holding to the back, and as he had already been badly bitten he didn't try it again by himself." It took four other people — including two white passengers — to drag her out of her seat. She later wrote in her legal testimony: "I resisted all the time, and never consented to go."

Ida B. Wells sued the railroad company for violating laws that guaranteed equal accommodation — and she won. At first: the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the verdict on appeal, and she was forced to pay court fines.

The lynching of her friends changed the course of Ida B. Wells' life

Thomas Moss, Will Stewart, and Calvin McDowell owned a grocery store in Memphis. They were incredibly successful, and according to the Scalar Institute, their success didn't go over well with the white owners of a competing grocery store. Those owners started spreading rumors about what was going on at the Black-owned People's Grocery, and things culminated on March 9, 1892 (via History). That was when a white mob lynched the three men.

Ida B. Wells was friends with the men, and their executions prompted her to investigate just what had led up to the lynchings. She went on to investigate other lynchings, too, to try to get to the bottom of what was going on. Local papers were reporting the lynchings often came after Black men were accused of raping white women, but the truth was very, very different. In the case of Moss' murder, it was driven simply by jealousy and anger over his successes.

Wells published her findings in the newspaper she co-owned. It was called the Free Speech, and when the report ran, an angry — and white — mob burned her offices to the ground. She was out of town at the time, and it definitely didn't scare her off. She wrote: "Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning."

Investigating lynchings and questioning stereotypes

At a time when lynchings could happen anywhere and at any time, Ida B. Wells decided she was going to investigate the executions that had happened over the previous decade. So, she got a pistol and headed out into the Deep South, where she traveled — alone — for months, and over the course of those months, she did a deep dive into the circumstances of around 700 lynchings.

According to The Guardian, she visited locations, collected photos and newspaper accounts, and she interviewed those who had been there. And remember — these are communities who organized picnics around executions, who laughed and headed off to a pick-up ballgame after dismembering a corpse and passing the body parts around to a cheering crowd. Wells had plenty of determination, but what she didn't have? Protection, practical or legal. She knew it, too, writing: "I had already determined to sell my life as dearly as possible if attacked. If I could take one lyncher with me, this would even up the score a little bit."

History says Ida B. Wells' work was in-depth and methodical, and adds she was one of the era's first investigative reporters. She compiled her findings in massive data sets, which were the forerunner of today's data journalism projects — projects undertaken to truly show the scale and shape of a problem too big to quantify in other ways.

Ida B. Wells' findings

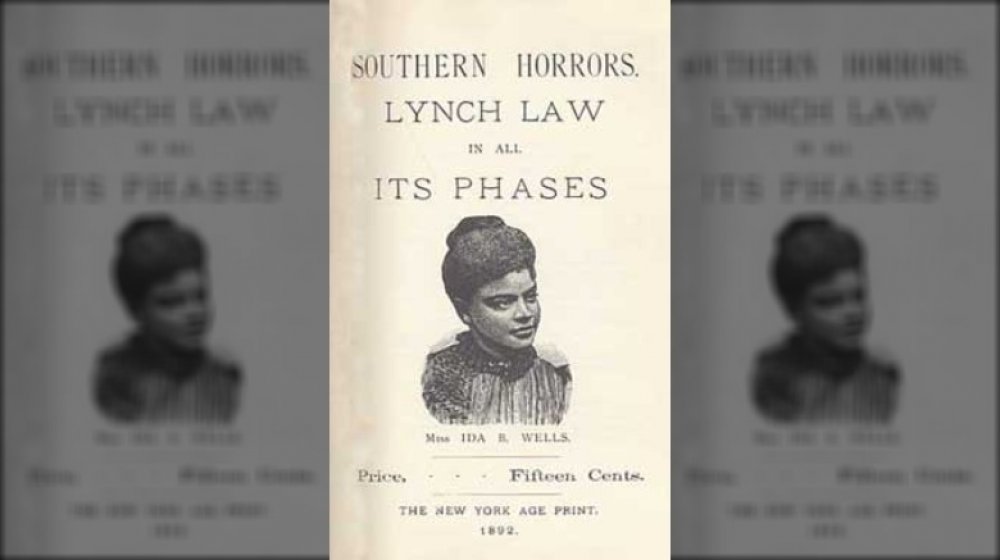

In 1895, Ida B. Wells published the Red Record, a pamphlet The Guardian says was "the first statistical record of the history of American lynchings." She also published works like Southern Horrors: Lynch-Law in All Its Phases, where she collected story after story of innocence.

The stories are heartbreaking, like the one of William Offett. He was accused of the rape of the wife of a minister, and it wasn't until he'd already served four of a 15-year jail sentence that she confessed it had been completely consensual. She started to fear she was going to give birth to a child and the affair would be discovered, so she'd accused him of rape. (Her husband immediately saw Offett released, and divorced his wife.)

Overwhelmingly, she found that white lynch mobs claimed the Black men they targeted had raped a white woman. For Wells, these were more than just cases of rampaging mob violence, they were instances of systematic violence, with a simple goal: fear and oppression. And the accusation of rape worked really well: defending someone accused of rape is a tough stance to take, and it meant others were less likely to come to someone's defense.

In the Red Record, Ida B. Wells compiled lists of the victims of lynching, and their "crimes." Prominent on the list are things like attempted rape and attempted murder, and "alleged" shows up a lot, too: alleged murder, alleged barn burning, alleged well poisoning. Also on the list? Self-defense, no offense, turning state's evidence, insulting whites, and race prejudice.

Death threats and leaving the South

Ida B. Wells absolutely got the attention of Southerners, Black and white alike. The publication of her findings that accusations of rape were almost always completely false kicked off a riot in Memphis, and an angry mob burned her newspaper to the ground. In 1892, the Boston Herald reported (via the Library of Congress): "to-day she is an exile from: her home, and threatened with handing or burning at the stake, should she return in 20 years, by the lawless mob whom she denounced in The Free Speech."

That was quoted by a Tennessee paper, the Columbia Herald, along with their editorialization on Wells. It's rough, but it's worth repeating: "[...] martyrs are cheap in Boston. The effete civilization [...] finds pleasant mental diversion in worshiping at the large flat feet of Ida B. Wells [...]. Ida Wells is worshiped as the licentious defamer of Southern women. The obscene filth that flows from her pen is chaste and classic literature to [Bostonians]."

In other words? Ida B. Wells wasn't just targeted by people who were mad at her for exposing the truth behind the lynchings, they were also mad because she exposed the lies of proper Southern women — and a Black woman, calling white women out on their lies? A horrendous sin in the eyes of the South. It's no wonder, then, History says Wells decided it was too dangerous for her to return home, and continued her activism in the North and abroad.

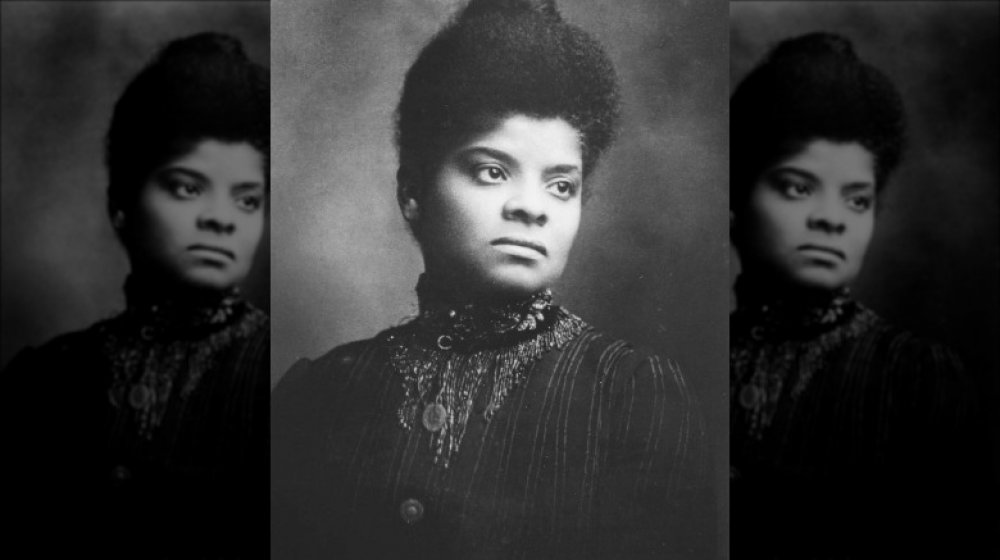

Organizing Chicago

In 1894, Ida B. Wells settled into her new home: Chicago. According to NPR, her presence there was like a whirlwind — her activism continued, and it shaped the city in some major ways, starting with her overhaul of the education system.

When Wells realized there was only a single, integrated kindergarten with a massive waiting list, she decided to establish another one — so, she did. She saw another need, too: Chicago's YMCA wasn't open to Black men, so she founded the Negro Fellowship League, with the idea it was going to do much the same thing as the YMCA: they helped people to find jobs and housing, as well as organized political and social gatherings. When the city didn't help her with funding, she took that on herself, too: during the day, she worked as a probation officer, and put her earnings back into the cause.

Ida B. Wells was also at the forefront of the suffrage movement, and it was an uphill battle. She founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, and even though they faced harassment from men who thought they should be home tending their babies and white women who wanted to make sure they got the right to vote first, Wells canvassed neighborhoods, educated her neighbors, and made sure they were registered to vote. In 1915, the city elected their first Black alderman.

Ida B. Wells organized a boycott of the World's Columbian Exposition

In 1892, Chicago was organizing something massive: the World's Columbian Exposition, a huge fair thrown to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' landing in the New World. The message of the fair, says The University of Chicago Library, was essentially to demonstrate to the world how far the US had come on its journey to utopia.

Ida B. Wells and other Black activists had a huge problem with this, and organized a boycott around a pamphlet called The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition. It was a damning report on exactly why the country was far from a utopia for its Black citizens.

Then, there were the exhibits at the fair itself, which PBS says were insanely offensive. Exhibits, literature, and artwork ridiculed non-white cultures, and historian Christopher Robert Reed says while yes, there were Black employees who worked at the fair, most were janitors, guards, or bathroom attendants. It was also here Nancy Green made an appearance as Aunt Jemima, and here's the heart of the problem for Wells and her fellow protesters. According to the University of Illinois Press, they were "being left outside the gates of the 'White City.'" Their contributions were ignored, and when they were mentioned, it was with the ridicule and stereotypes of the Aunt Jemima pancake exhibit. Ida B. Wells — along with Frederick Douglass — handed out thousands of copies of their booklet during the fair.

When the NAACP just wasn't enough

In 1908, activists gathered in New York City, brought there in response to the riots that had broken out in Springfield, Illinois the previous year. Ida B. Wells — now Ida Wells-Barnett after her marriage to Chicago lawyer and editor Ferdinand Barnett (via The Guardian) — was one of the attendees, and became one of the founding members of the organization that came from the conference: the NAACP.

The idea, says History, was that the organization was going to work to overcome prejudice, and to push the cause of equal rights. While it seems like that would be right in line with Wells' thinking, she wasn't a huge fan — and they weren't a fan of hers, either.

Just what happened varies by the telling. According to the Library of Congress, Wells had become inactive in the organization by 1912, citing problems with "white leadership and moderate stance" as a reason for striking out on her own again. According to The Guardian, though, there was another side to the coin: they ousted her because they thought she was too radical.

Ida B. Wells definitely didn't get along with the white suffrage movement

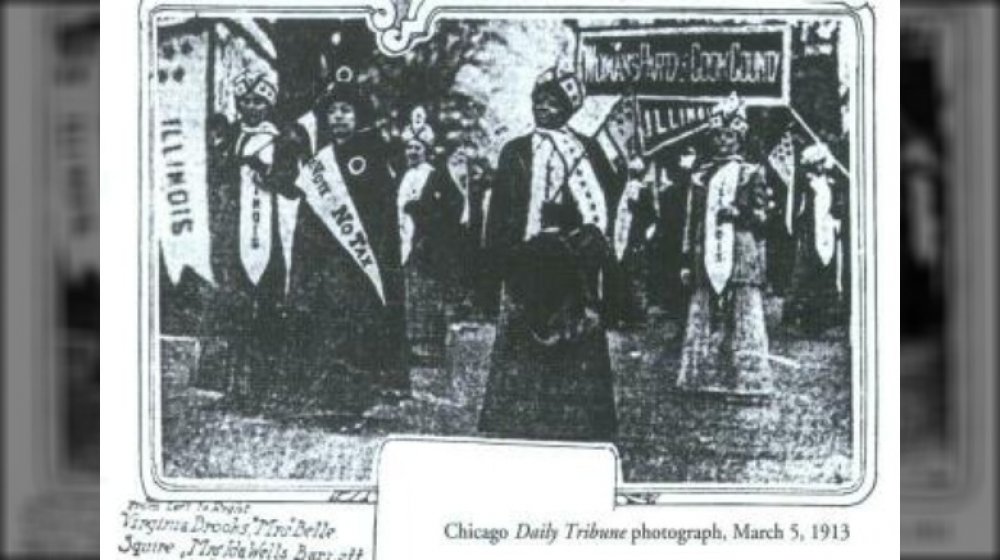

At a glance, the suffrage movement seems pretty straightforward: women wanted the right to vote. But it wasn't that easy, as Ida B. Wells found out first-hand in 1913.

That's when the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) marched in Washington, DC. Groups of representatives from various states were present, including groups of women from the South. Women who, says the Northern Illinois University Library, were still holding onto the old beliefs of white supremacy. Because they were still fans of racial segregation, their branches of NAWSA were less concerned with getting every woman the right to vote, and more with getting white women the right to vote. So, when Wells went with her integrated group from Illinois, there was a massive problem: they were told Black demonstrators had to line up in their own section, not with the white residents of their state. Wells refused, and the Illinois contingent? They sort of shrugged and told her not to march.

Wells left, but quickly reappeared: she headed into the crowd along Pennsylvania Avenue, and when her group walked by, she stepped out and joined the only two white women who had supported her. Seven years later, the 19th Amendment guaranteed all women the right to vote... regardless of race.

Ida B. Wells had issues with the Women's Christian Temperance Union, too

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union was founded in 1874, and at the top of their list of concerns was alcohol. According to the Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries, they were the ones holding pray-ins at bars, and pushing the sale of alcohol out of their towns.

Ida B. Wells did not like them. Specifically, she didn't like Frances Willard (pictured), who became president of the WCTU in 1879. Under her leadership, it became a much more political union, and she firmly believed if women had the right to vote, they'd vote to end alcohol. And she firmly believed the way to get women the right to vote was through the South — she wanted to court the white female vote, and condemn alcohol by labeling it as the fuel that drove Black men to rape and murder their way across the states. In 1890, she told the New York Voice (via NPR), "'Better whiskey and more of it' is the rallying cry of great, dark-faced mobs. The safety of [white] women, of childhood, of the home, is menaced in a thousand localities."

Which is, of course, exactly what Wells proved was false during her investigations into the true motivations behind lynching. In the Red Record, Wells devoted a whole section to the dangerous attitudes of Willard and the WCTU, condemning her "studied, unjust, and wholly unwarranted attack upon our work."

Ida B. Wells had a plan to fix things

Ida B. Wells didn't just shine a light on the horrible truth of some of the most brutal crimes of the American South, she had ideas on how to set things right. In the Red Record, she says Black men and women need to be given the same right to defend themselves against accusations as white men and women. In a court, a person needs to be proven guilty. Before a bloodthirsty mob, she wrote, he needs to be proven innocent, and "no evidence he can offer will satisfy the mob; he is bound hand and foot and swung into eternity." What is the ordinary person to do? Start with talking about the facts and spreading the truth: "Let the facts speak for themselves, with you as a medium."

She advocated for people who were members of societies, organizations, and churches to take it upon themselves to help make sure the actions of those organizations stay true to their principles, and to protest lynchings and other injustices when they see them. Financial power is important, too — she stressed people should refuse to invest in the businesses of cities and towns where mob justice ruled, and that everyone should take it upon themselves to let their government know they want a world where everyone really, truly is equal.

Ida B. Wells died in Chicago in 1931, after, says The Guardian, an illness related to kidney failure. She was 68-years-old.