We Now Understand Why The Arab Empire Crumbled

In 1258, Baghdad, the seat of the Abbasid Caliphate and the heart of what was effectively the Arab empire fell to the besieging army of Ghengis Khan's grandson, Hulagu Khan. In a movie or a TV series, this would make for a properly dramatic finale — if we cut out the preceding decades of decline that generally seem to mark the fall of empires. The truth is the decline of the Abbasid Caliphate began long before its symbolic sacking.

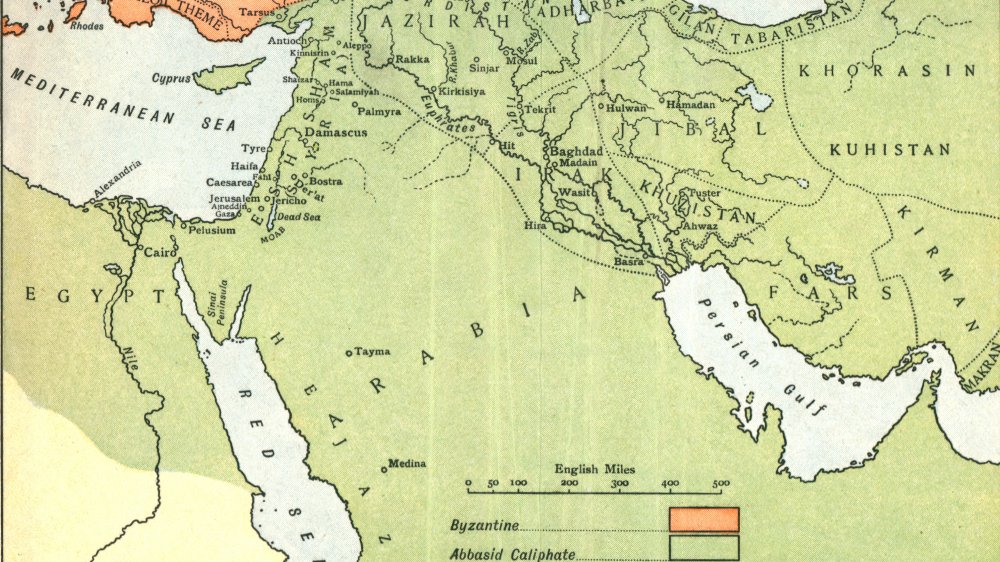

By 750, the Abbasids had established a caliphate that stretched from modern-day Tunisia to Pakistan through a revolution against the Umayyads, who had lost the support of their multi-ethnic country by ruling purely for ethnically Arab Muslims. The Abbasids did little to change the actual structure of the caliphate, however, and in the space of 200 years its influence further disintegrated. The economic drain of sustaining an army big enough to keep a cohesive empire and fight off the Crusades and invasions carried out by the Iranian Buyids and Seljuq Turks proved too much, according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia. By 950, the Abbasids served a similar role to our contemporary English monarchy, important culturally but effectively powerless to actually rule anything.

Not with a bang but a whimper

What the cinematic details obscure, however, is the way that the force of geography breaks empires apart. In a paper for Der Islam, Professor Hugh Kennedy of SOAS University of London traces similar patterns in the British Empire. An empire can only hold together with a pan-imperial elite, for example, British governors heading out to Canada and New Zealand to exert influence in person. Eventually, though, local authorities start doing more of the work, fragmenting the unified identity of the imperial project.

As mentioned, the country the Abbasids took from the Umayyads was multi-ethnic, but they failed to adequately address this fact. Rather, the Abbasids contented to rule from a distant Baghdad. In some corners of the empire, like in Egypt, officials started to style themselves as independent rulers. In others, like in Yemen, the local populace returned to their original tribal structures. None, however, openly revolted. Rather, by 935 — over three hundred years before the Abbasid's final defeat — their subjects achieved a level of independence by wielding power independently from the caliphate while pulling from local traditions to ensure their legitimacy.

No empire ends gracefully. In this case, however, it seems more like people simply chose to move on before it finally died.