The Untold Truth Of Jim Crow

History is complicated. We're all taught that after centuries of slavery in the US, it finally came to an end with the Civil War. There were somewhere around 4 million people held in slavery in 1860, and according to History, about a third of the Southern population were slaves. We know that Abraham Lincoln made the end of slavery official on January 1, 1863, by declaring "slaves within any State... shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free." That was followed by the 13th Amendment in 1865, but again... history is complicated.

Even as other amendments were added to the Constitution, less official laws were also being put in place. The so-called Jim Crow laws quickly became a guiding principle for life in the South, and according to historian Douglas A. Blackmon (via National Geographic), they created "slavery by another name." What were they, and how bad was life living underneath them?

It was really, really bad.

What were Jim Crow laws?

After the Civil War, Southern states moved quickly to try to limit the impact emancipation had on their way of life. According to National Geographic, that was first done by the enacting of "black codes," written against the template of the slave laws that had just been taken away.

In response, Congress passed the 14th and 15th Amendments, which guaranteed equal protection and citizenship, and voting rights, respectively. But in 1877, the country got a new president — Rutherford B. Hayes — who promised to be pretty hands-off when it came to the South and how they went about their business.

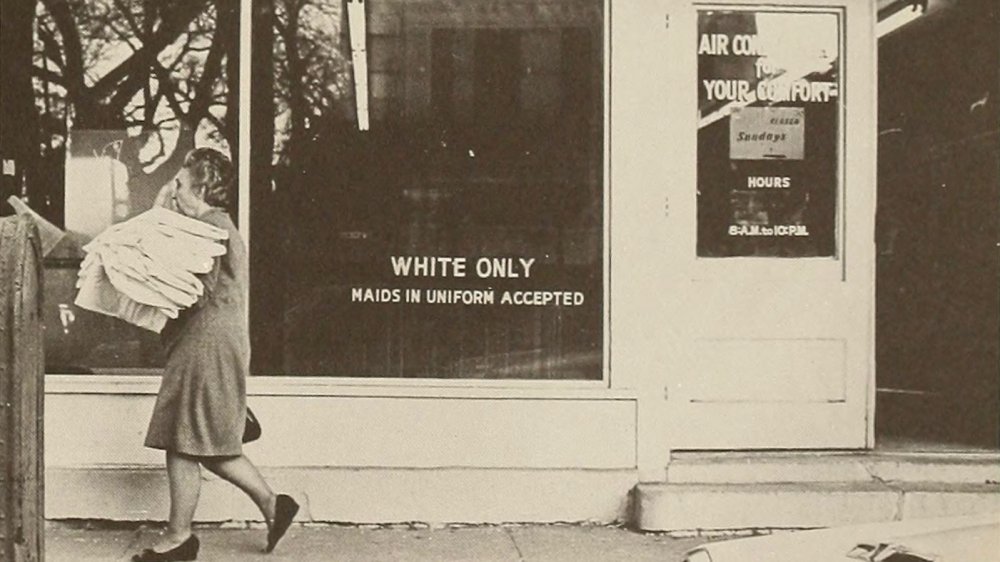

As a consequence, hundreds of new laws were put in place by Southern states, all designed to establish entirely separate worlds for black and white citizens. On paper, many theoretically appeared to give both groups equal treatment, but the reality was very different. "Separate but equal" was a massive misnomer, with black citizens all but forbidden to interact with whites, forced to use public facilities that were grossly inadequate, and kept from the polls in some insane ways. These new laws were strictly enforced by law enforcement happy to uphold them and by the widespread practice of lynching. They became known as the Jim Crow laws, and they stood well into the 20th century.

The Supreme Court said it was A-okay

According to National Geographic, there was one court case in particular that set the precedent for Jim Crow: Plessy v. Ferguson. So, what exactly happened? In 1892, Homer Plessy agreed to be at the forefront of a case testing the extent of the South's new policy of segregation. Plessy — who described his lineage as of "seven-eighths Caucasian and one-eighth African blood" — bought a train ticket to go from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana. He took a seat in the whites-only section and refused to leave when he was told to. He was arrested, convicted of violating the new laws, then filed an appeal stating that the law violated the new amendments that had been written to guarantee equality for all citizens.

It wasn't until 1896 that the Supreme Court delivered their ruling: separate-but-equal facilities, they said, were absolutely constitutional. How the heck is that possible? The 14th Amendment, they said (via History), only covered a person's civil and political rights, not their social rights. Any claims that facilities weren't actually equal were, according to Justice Henry Brown, "because the colored race chooses to put that construction on it."

There was only a single dissenting vote on the ruling that opened the door for Jim Crow laws. Justice John Marshall Harlan, a former slave owner from Kentucky, wrote that the verdict was "wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution."

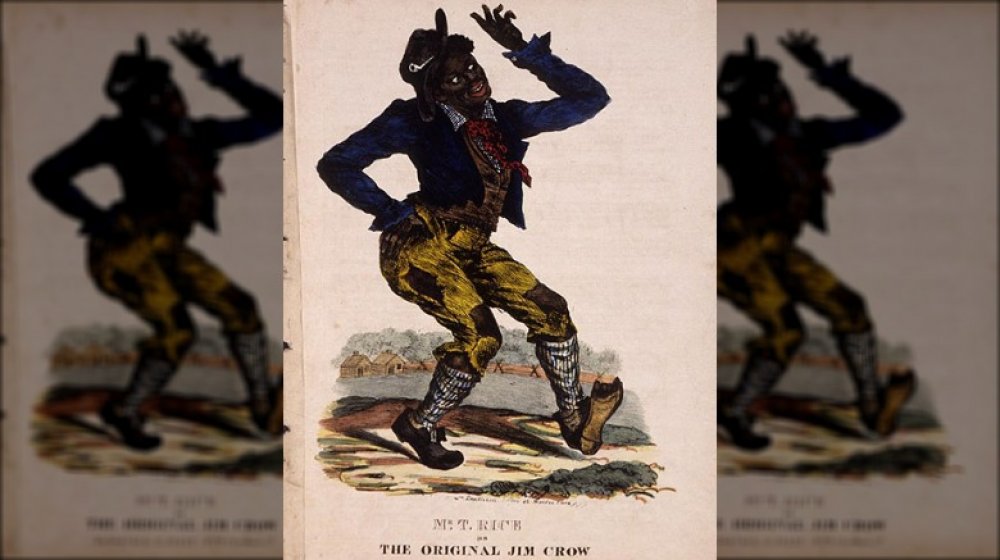

Jim Crow was the name of a travelling entertainer's blackface character

The post-Civil War era laws restricting almost every aspect of life for America's black citizens were called Jim Crow laws because there really was a Jim Crow... sort of.

In 1828, an entertainer named Thomas Dartmouth "Daddy" Rice took to the stage in one of the first instances of blackface: a white man, he used a burnt cork as makeup and sang a song he claimed he'd heard either from an old black slave, or a black stable hand. What the true story is, is unclear, but the song — which included the line, "My name is Jim Crow." — was a massive success. Rice's character became a sort of standard character in minstrel shows as they became more and more popular. USF's History of Minstrelsy says Rice became known as the "Father of Minstrelsy" after the nationwide success of his shows, and his establishment of a formula that would be carried on by other groups.

According to Ferris State University's Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, "Jim Crow" had become a "collective racial epithet" as early as 1838. Even as minstrel shows continued to paint a dehumanizing picture of black stereotypes, one of the most commonly used names was adopted by segregationists. Rice didn't live to see it applied to the new slave codes of the late 19th century: he died a poor man in 1860, having spent his fortunes on an insanely lavish lifestyle.

Jim Crow and the KKK

In the winter of 1865 into 1866, six Confederate veterans organized what PBS describes as "a homegrown American terrorist organization": the Ku Klux Klan. While it started out as more of a harmless, secret fraternity, things escalated very quickly alongside the introduction of the 14th and 15th Amendment. Members of the KKK took it upon themselves to make it well known what kind of violence was going to be visited upon any black citizens who tried to do things like vote, as well as any white citizens who stood with them. When, in 1870, Hiram Rhodes Revels and Joseph Rainey became the first black men elected to the US Senate and House of Representatives respectively, the KKK decided they needed to stop black voters.

According to National Geographic, the federal government reacted to the KKK quickly: in 1871, laws were enacted that allowed a president to declare martial law. They were used, too — nine counties in South Carolina were quickly placed under martial law and members of the KKK were arrested. Still, the organization as a whole continued to terrorize the South, building a laundry list of atrocities like the whipping of a 103-year-old woman. There were countless murders and lynchings, some for "crimes" such as possessing a book.

That incarnation of the KKK dissolved in the 1870s: with the adoption of Jim Crow laws, they had gotten exactly what they wanted.

Some Jim Crow laws you haven't heard of

When it comes to the Jim Crow laws that governed life in the South, there's some that are talked about more than others. We've been taught about things like separate train cars, separate seating areas on buses, and separate drinking fountains, but that's just the tip of the iceberg. According to the National Park Service, states enacted their own laws that may or may not have applied elsewhere. Take Georgia. Head there, and you'd find cemeteries and graveyards were segregated, too — so were mental hospitals, restaurants, beer and liquor stores, and it was forbidden for a black barber to cut the hair of a white woman or girl.

Hop over to Oklahoma, and you'd find separate, segregated phone booths — and if you didn't, you were well within your rights to demand it of the Corporation Commission. Also in Oklahoma, teaching in an institution of any kind that accepted both white and black students was an automatic misdemeanor.

In Florida, if a mixed race pair were caught living together, it meant a fine and up to a year in jail (via The Jackson Sun). Textbooks in North Carolina schools were, by law, restricted to people of the first race to use them, and libraries were segregated, too. And in Louisiana, they took care to enact a law that said not only housing facilities and rentals were to be completely segregated, but buildings dedicated to the education and care of the blind were, too.

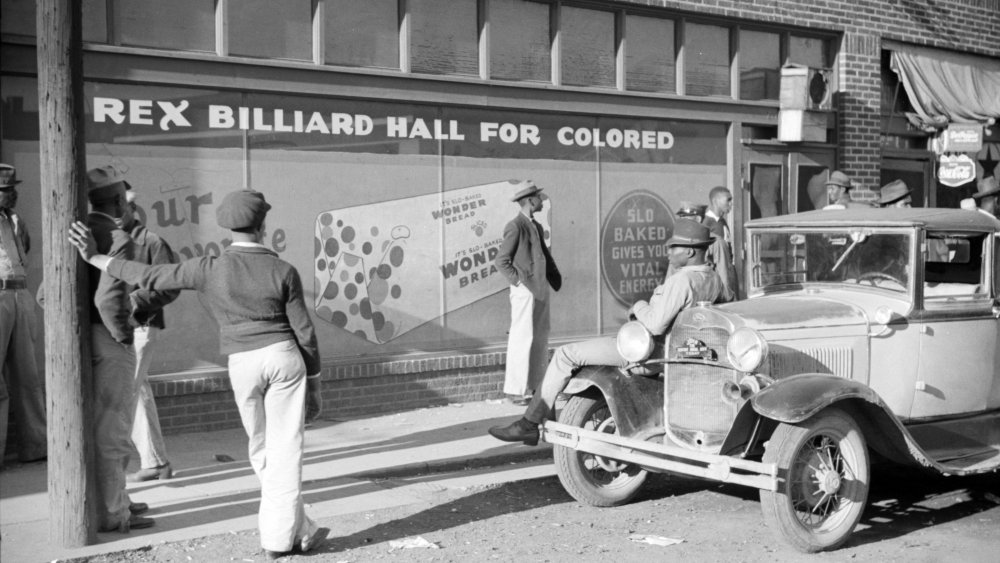

The Jim Crow laws you've never heard of: games, parks, and fun

Jim Crow laws extended to recreational activities, too — and some were, well... extensive. In Georgia, they really, really wanted to keep their baseball separate. Not only were even amateur teams either white or black, but a white team couldn't play on a field within two blocks of an all-black playground, just as a black team couldn't play on a field within two blocks of a playground dedicated to white children. Parks were also kept strictly segregated, too.

Louisiana apparently loved their circuses, because there were laws requiring them to have separate ticket offices, ticket sellers, and entrances, no less than 25 feet apart (via The Jackson Sun).

Virginia required their theaters to have segregated seating, Oklahoma's Conservation Commission segregated fishing and boating events, along with restricting bathing activities. And in Alabama, even a simple game of billiards was quite literally off the table: black and white players weren't allowed to play together, or even hang out together while one person played.

Promoting equality went against Jim Crow laws in a very concrete way

Supporters of Jim Crow, says Ferris State University's Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, were huge fans of repeating the idea of things being "separate but equal," even as there were blanket laws about white drivers automatically had the right-of-way, and how blacks were required to use "courtesy titles" — Mr., Mrs., Sir, Ma'am — when talking to a white person, but were in return every only addressed by a first name.

And even as "separate but equal" continued to be pushed, well, take Mississippi. According to the National Park Service, there were laws on the books that dealt with "suggestions in favor of social equality." Anyone who wrote or printed material, anyone who circulated said material, and anyone who even made vocal arguments about how blacks and whites were equal and should be treated that way would be found guilty of a misdemeanor. And that charge? It came with the possibility of a jail sentence of up to six months and/or a $500 fine... which doesn't sound terrible, until you consider that adjusted for inflation, $500 in 1900 is the equivalent to around $15,500 in 2019.

Passing a literacy test was required to vote

Part of the goal behind Jim Crow wasn't just segregation, but also suppressing the black vote. One way that was done — well, aside from outright threats of violence — was the establishment of literacy tests. In order to vote, the theory went, voters needed to be able to read, write, and/or pay a required fee to open up the polls. How much of an impact did these have? ThoughtCo. puts it this way: in 1896, 130,334 black voters registered. In 1904 — after the literacy tests and fees were put in place — that dropped to just 1,342.

And many tests were insanely unfair. Questions were often written in such a way that there were a few potentially right answers, and it was up to the test administrators to decide which was correct... and who passed. Some asked questions about things like civil procedures, laws, and citizenship, says Slate. But some — particularly one example from Louisiana — were insanely devious. There were 30 questions, it needed to be completed in 10 minutes, and a single wrong answer meant a fail.

Now, try these two questions as samples: "Print a word that looks the same whether it is printed frontwards or backwards." Now, how about this one? "Write every other word in this first line and print every third word in the same line, [the original type was smaller and the first line ended at comma] but capitalize the fifth word that you write."

The year of that test was 1964.

The town founded as a safe haven from Jim Crow

Not all of the South was a terrible place where segregation, discrimination, and hate ruled in the name of Jim Crow. In 1887, former slaves Isaiah T. Montgomery and Benjamin T. Green founded the town of Mound Bayou. It started out as 840 acres of dense, heavily forested Mississippi swampland, but the little group of settlers tamed the land and turned it into prime real estate. By 1924, it was a thriving — and autonomous — town with no Jim Crow laws (via NPR).

The Mississippi Historical Society said that Montgomery lived to see his town expand to 800 residents, and a further 30,000 acres were added onto the outskirts. (That's his house in the photo.) There were more than 40 stores, along with schools, churches, lighted streets, and so little crime that there really wasn't a need for a jail. The Taborian Hospital opened in 1942, a Carnegie library was built, and a train station opened up access to the entire Mississippi Delta.

The town continued to thrive until the years following World War I. The post-war era brought depression with it, and the town — like many other small, agricultural-based towns of its size — started to decline. It's still there, even though the hospital is boarded and shuttered and the founders' homes are abandoned. But residents still observe an annual Founders' Day and lay a wreath during a graveside memorial service for Montgomery and Green.

Jim Crow, marriage, and the Racial Integrity Act of 1924

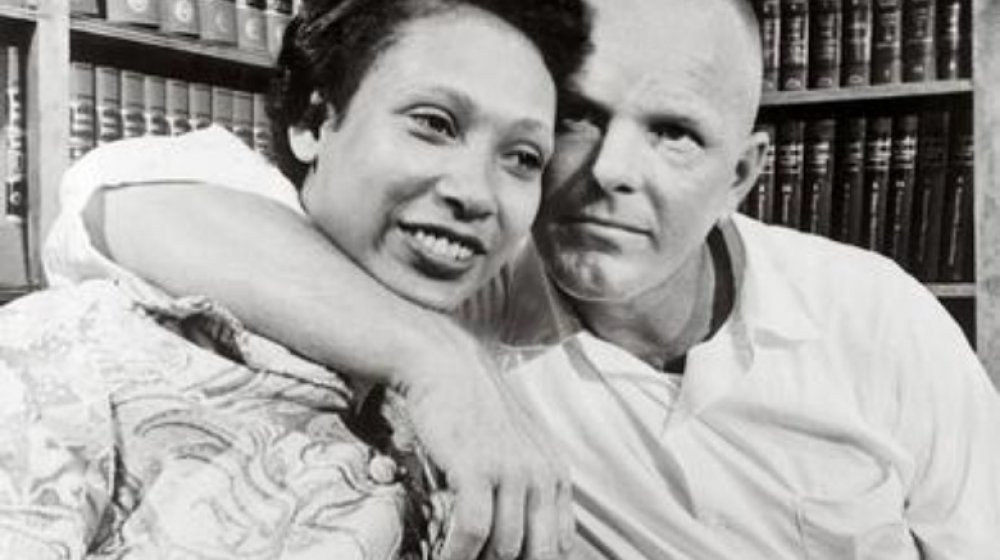

It was the 1950s, and seriously, all Richard and Mildred Loving wanted to do was to live their lives in happily married peace and quiet. But they lived in Virginia, so it was one day in 1958 that they were woken in the middle of the night and arrested. Their crime? He was white, she was black, and they were married. They had gotten married in Washington, D.C., where they actually could get a marriage license. But once they returned to their home and their family in Central Point, Virginia, they were told that what they were doing was against the law.

The reason for that, says The Washington Post, was Walter A. Plecker. In the early 20th century, he was in charge of Virginia's Bureau of Vital Statistics. He was also a white supremacist and a proponent of eugenics. While many states had Jim Crow laws on the books forbidding marriage between a white person and any minority (via the National Park Service), Plecker championed legislation that would become the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. Not only was interracial marriage criminalized, but every birth certificate had to have one of two boxes checked: "White" or "Colored."

According to Biography, things only changed when Mildred Loving wrote to Robert F. Kennedy and asked for help. Kennedy pointed her in the direction of the ACLU, and when their case went before the Supreme Court, it was overturned — unanimously.

An early strike against Jim Crow

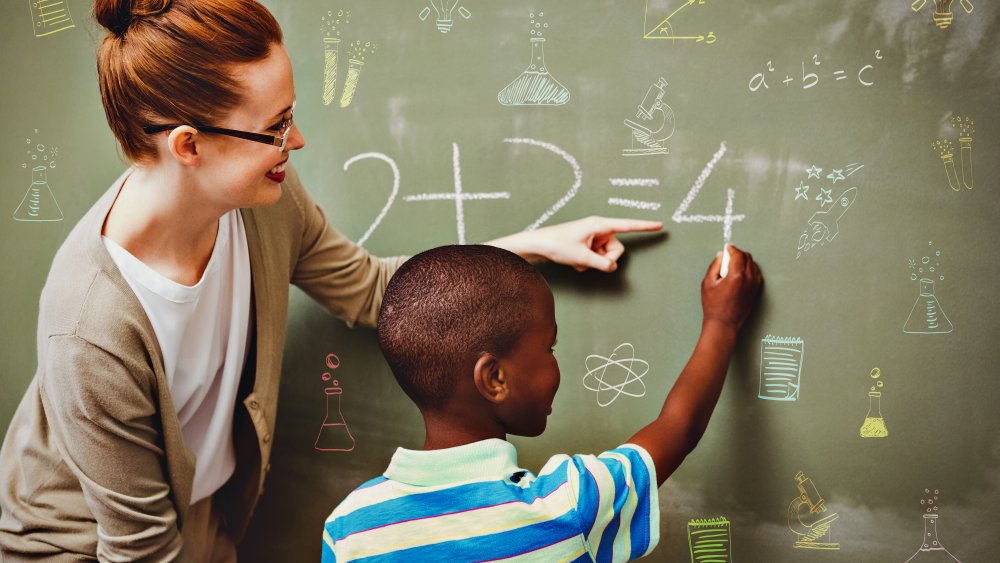

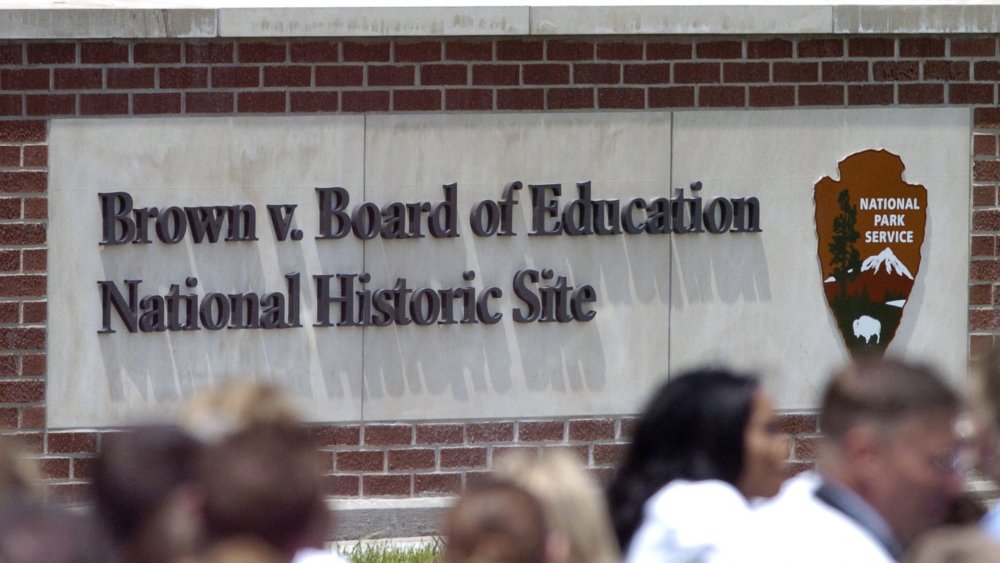

Jim Crow laws were the norm for decades, and it wasn't until 1954 that a single court case struck the first blow toward dismantling the discriminatory institution.

That was Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, and it was a class-action suit brought by Oliver Brown. At the heart of it was his daughter, Linda, who had been refused entrance to the all-white elementary schools in Topeka. Brown argued that the schools absolutely were not equal, and that was a direct violation of the 14th Amendment (which guarantees all citizens equal protections).

According to History, it wasn't an easy fight. The US District Court in Kansas originally agreed that yes, it was a bad thing, but stuck to upholding the idea of "separate but equal." And for a bit, it looked like the Supreme Court was going to go that way, too: until, right before the case was heard, Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson — who believed whole-heartedly in the precedent set by Plessy V. Ferguson — died. He was replaced by Earl Warren, who spearheaded a unanimous verdict in favor of integration, summed up simply (via PBS): "... the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."

The end of Jim Crow?

Jim Crow laws very, very slowly started to get pushed by the wayside, beginning with Brown v. Board and President Harry S. Truman's integration of the military. That, says The University of Southern California, came in 1948, but it was still years before other legislation was passed to outlaw discrimination and segregation in other areas.

After decades of protests and struggles, President Lyndon Johnson finally signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law: written mostly during JFK's administration, the heart of the bill was that all Americans — regardless of race (or sex) — were to be treated equally in all areas of life. Discriminatory voting laws fell not long after with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

Even though America knew for a long time that there's really no such thing as separate but equal, Jim Crow laws hung around anyway... and here's the thing. Dismantling them happened only a bit at a time, and as the Ferris State University's Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia points out, these stereotypes — and merchandise that promotes them — are still being sold in the 21st century.