The Tragic True Story Of The Tulsa Race Massacre

The story of the Tulsa Race Massacre is a dark spot in American history that the country tried to hide behind a cheap painting, so to speak. It was one of the greatest tragedies to occur on United States soil, as well as one of its deadliest events. An entire city district was destroyed in less than a day by a mob composed of delusions of white supremacy along with a hefty helping of government negligence, guns, and torches. And thanks to decades of silence, you've probably never heard of it.

Racially motivated violence is nothing new to the US — history would say the country was built on it, and trying to hide that violence is nothing new, either. But these incidents, to put it mildly, have had lasting effects for Black Americans and the country as a whole. Though the massacre occurred between May 31 and June 1, 1921, Greenwood, once a prosperous Black district in a segregated Tulsa, Oklahoma, will never be the same. And once you know the story, you probably won't, either.

Before the massacre, Greenwood was known as "Black Wall Street"

Leading up to the Tulsa Race Massacre, the city was heavily segregated. Most of Tulsa's Black residents lived in a district known as Greenwood, and Greenwood was thriving. It functioned as a self-contained community and a hub for Black commerce. Walking into Greenwood, you could find everything: clothing boutiques, jewelry and grocery stores, schools, and churches. There were doctors and real estate agents. Greenwood had their own library as well as the Tulsa Star, a Black-owned newspaper, according to History.

The district was separated from white Tulsa via railroad tracks, which served as a boundary that encouraged Black businesses to stay in the community. Not that they had much choice. Given the location limitations imposed by segregation, the Greenwood district was the most logical choice both logistically and for safety. Before long, Greenwood Avenue became known as "Black Wall Street."

The community couldn't have reached its economic peak without bringing in money from the outside. Many Greenwood residents still worked jobs on the bottom of the societal ladder in other, whiter parts of Tulsa, but they spent the money they earned within their own community. This had the effect of consolidating wealth into Greenwood.

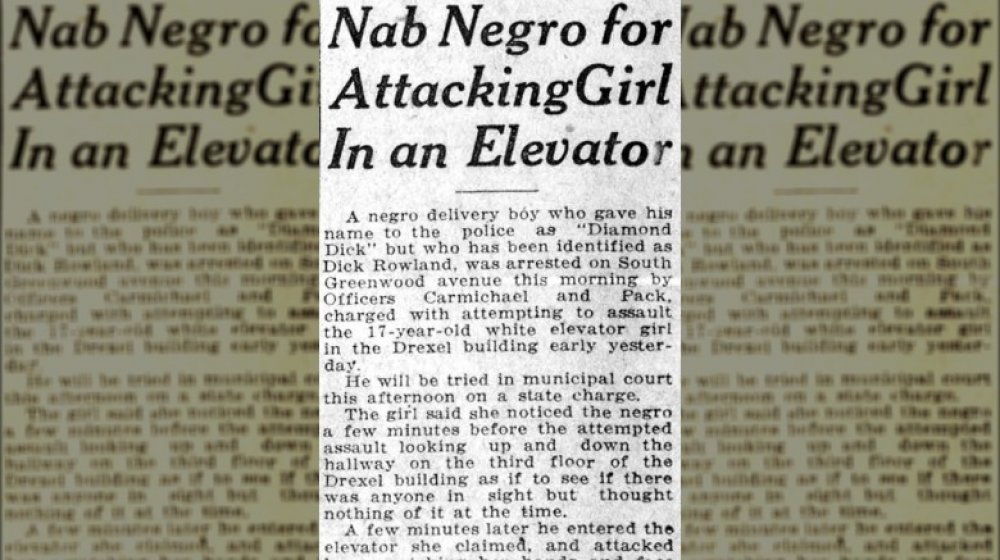

The instigative article that kicked it all off

The Tulsa Race Massacre kicked off with a pretty vague situation. The story goes as such: a young Black man by the name of Dick Rowland hopped on an elevator that was occupied by a white woman, Sarah Page. Page screamed, and Rowland, being Black in a time of heated race contention, ran away. He was arrested later that night for sexual assault.

Here's where the story gets a little weird: Little is known about Page or Rowland, including the ages of the two, their actual names, or the situation that might have surrounded the two before they ended up in the elevator together. Rowland is often said to have been a shoe shiner or delivery boy and may have actually been named John Rowland, according to Tulsa World. Page would disappear entirely after the massacre, and Rowland may have skipped town and died on the East Coast some time after the charges were dropped at Page's request. That came after the Tulsa Tribune printed an article that raised tensions to their breaking point.

The article pointedly portrays the charges brought against Rowland and a story of the events that would rile up anyone, claiming that the young man had been "looking up and down the hallway" to make sure the coast was clear. It goes into further detail of the alleged assault itself in a way that made Rowland look like a violent offender.

An armed confrontation at the courthouse

The rumors spread, both of the allegations against Rowland and of a possible lynching that night, between both of the highly segregated communities following the article, which was released on the day the massacre began. Rowland was initially held in the city jail, which was reported to have been an inadequate place to house detainees, but was moved to the county jail on the top floor of the courthouse following a threatening phone call received by police.

In the evening, a wave of 25 armed Black men came to stand guard in front of the courthouse against a mob of angry white people, but they were ushered away by the sheriff, according to the book Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its Legacy. Later on, a second wave of 75 armed Black men showed up for the same purpose. At this point, according to Tulsa World, Rowland had been barricaded in the jail and was being protected by the police. That second wave of local guardsmen was met by a force of over 1,500 angry whites, some of whom were armed.

A struggle ensued when a member of the mob tried to disarm one of the Black men protecting Rowland. The gun went off into the air like the starting pistol of a race, and all hell broke loose.

Greenwood was burned to the ground

The armed Black group that had been protecting Rowland were severely outnumbered by the white mob that had gathered. After the first shot rang, they were pushed back, retreating to Greenwood. The mob followed, and more joined them.

The violence brought by the white marauders was among the worst in history. They set fire to Greenwood in a fury of radical white supremacy and burned the district to the ground. The ashes of 35 city blocks covered the ground where houses, businesses, and other institutions used to be. The buildings that weren't burned were looted. Black citizens of Tulsa were slaughtered, many of whom were trying to find refuge as they watched their property set ablaze. The numbers are staggering: Around 10,000 Black people were left homeless, between 100 and 300 were murdered, and at least 800 were injured, according to Tulsa History.

When firefighters came to put out what flames they could, people in the mob pointed guns at them and threatened them until they packed up their hoses, according to reports – anything to prevent them from saving what was left of Black homes and businesses. The once-great district of Black Wall Street would never again prosper the way it had before the attacks.

White men were deputized ... and then participated in the violence

As events unfolded during the Tulsa Race Massacre, reports say that the city deputized many white citizens to help to control the out-of-control situation, but any official city sources would find it in their best interest to make themselves look helpful. Make of that what you will. Regardless, many of those deputized citizens didn't help control the mob but, instead, went in the other direction.

According to The New York Times, hundreds of white people were deputized by city officials who went out of their way to arm them, commandeering weapons from gun shops and putting them into the hands of people who would join the violence. There's no way to know if the intent was to arm the mob or if, in a moment of absolute stupidity, the city made a judgment call that would backfire and add to the atrocities in Greenwood.

An account by the NAACP assistant secretary who arrived in Tulsa after the massacre had begun backs up this claim, according to Riot and Remembrance. The book states that the assistant secretary (who had blond hair and blue eyes) was offered deputization although the officials knew nothing about the out-of-towner. It goes on to state that the National Guard reported that 500 men were deputized in total and that the police chief had no clue that these angry white people would join the angry white mob.

6,000 Black citizens were arrested

The massacre officially ended on June 1, after the governor deployed the National Guard to Tulsa, but the Guard wasn't as helpful as they could've been. Sure, the massacre ended with their help, but they also arrested and detained 6,000 of the city's Black citizens, according to the Zinn Education Project. A news report from the time also stated that the National Guard fired a machine gun from the top of a grain elevator into a large group of Black Tulsans, killing around 50. Of course, the National Guard denied this.

The official reason for detaining all the Black citizens the Guard could get their hands on and packing them into the Convention Hall amounted to safety concerns, and the conditions for their release were appalling. According to Tulsa World, the only way the detainees could be released was if a credible white person — an employer or the like — vouched for them. The Convention Hall quickly became filled beyond its capacity, and secondary locations were needed to house the detained population. All but 1,000 or so of the detained Black Tulsans were released by June 2. The rest would be released by the end of the month. Once released, they were required to wear identification cards to avoid being arrested a second time.

They tried to cover the massacre up

There's a reason why most people don't know about the Tulsa Race Massacre: Officials didn't want them to. It wasn't like the government tried to make it disappear a decade later, either. It started at the beginning. There were initial news reports from the area, and the statements regarding the violence put the death toll at around 36, according to Britannica, which we now know only accounts for a fraction of the victims. Funerals for the dead were denied, the government blocked all lawsuits filed by victims of the attack, the news and officials blamed Greenwood residents for the massacre, and so on. They purposefully muddled the history and essentially wiped it from the books for decades, according to the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties of the House of Representatives in 2007.

The city refused to investigate the massacre at all. According to Human Rights Watch, the only person to ever be charged for the massacre was the police chief, and the charges were for negligence. He lost his job and had to pay a fine. There was a media blackout over the event, and soon, nobody talked about it anymore. According to Tucson Weekly, this isn't new. Cover-ups of atrocities committed against people of color have happened for as long as white people have been committing them. For example, you've probably never heard of the 1898 Wilmington Massacre or the 1968 Orangeburg Massacre.

The Tulsa Race Riot Commission wasn't established until 1997

Most of the information about the Tulsa Race Massacre was discovered by the Tulsa Race Riot Commission after it was established in 1997. The commission was brought through a law passed in Oklahoma designed to give the committee the authority needed to investigate the massacre, you know, because it had been covered up until that point. It took 76 years for the massacre in Tulsa to be investigated.

According to The New York Times, the commission managed to discover thousands of documents. The documents and investigation proved that the massacre occurred, that the city of Tulsa was responsible for it as well as the subsequent hurdles to rebuilding efforts through negligence or malice, and that they had purposefully made it disappear from history, according to Justia US Law.

After the commission released its official report in 2001, it called for $33 million in reparations to be paid, citing the fact that lesser incidents had been sufficient cause for reparations in the past. It was dismissed in 2005, but the fight for reparations was picked up this year by Human Rights Watch.

Potential mass graves were discovered nearly 100 years later

Though the investigation into the Tulsa Race Massacre was thought to have closed following the commission's report in 2001, it was rejuvenated in 2018 when Tulsa's mayor, G.T. Bynum, ordered a new investigation into potential mass grave sites with connections to the massacre.

As disturbing as it is, the unidentified victims of the massacre were said to have been buried in mass graves, and oral traditions passed down from the event hinted at where these graves might be located, according to NPR. As reported by The New York Times, archaeologists from the University of Oklahoma had gathered enough evidence in 2019 to confirm two mass grave sites that might indeed hold the previously erased deceased. Using ground-penetrating radar, soil samples, and other archaeological magic, these scientists were able to build a strong enough case for potential mass graves along the Arkansas River and within the Oaklawn Cemetery to have excavation approved after they jump a few more procedural hurdles. The archaeologists felt it was better to wait on the excavation so that the disinterred bodies of the deceased weren't just sitting around while the scientists figured out their next steps.

The Tulsa Race Massacre wouldn't be recognized as such until the 21st century

You'll notice in this article that we use the term "massacre" instead of the term "riot" when referring to the Tulsa Race Massacre, which has historically been a heated point of contention between those who are affected by the oppressive circumstances surrounding race massacres like this one and those who don't understand what words mean. In fact, according to Tulsa History, the massacre is believed to have only been designated as a "riot" in the first place so that insurance companies didn't have to pay out for the destruction, injuries, and death in Greenwood. Unfortunately, "riot" was the more common term up until recent years.

Following the disbanding of the Tulsa Race Riot Commission after their report, a new commission was formed in 2017, the Tulsa Race Riot Centennial Commission. This commission changed its name to the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission after receiving community feedback, believing that "riot" was purposefully used to downplay the tragedy. Oklahoma State Senator Kevin Matthews, head of the commission, said about the name change, "They named it a riot. We didn't name it a riot. People in my community started to tell me if we were going to tell the history, we needed to tell it from our perspective." And that was that. What was once a "riot" had been properly renamed a massacre.

The Tulsa Race Massacre was only recently taught in Oklahoma schools

The Tulsa Race Massacre isn't required to be taught in public school curriculums throughout the majority of the country, and you'd be hard-pressed to find it in any textbooks outside of Oklahoma. That being said, you'd learn all about if you were sitting in an Oklahoma high school history class, thanks to a legal mandate requiring it.

Obviously, because of attempts to sweep the massacre under the rug, it wasn't taught in schools until recently. In 2000, according to Tulsa World, it became a state Department of Education requirement for all high school Oklahoma History classes and for all US History classes in 2004. It was added to the Oklahoma history books in 2009. The state senate then passed a bill mandating all of this, things that were already happening, in 2012. Unfortunately, as of May 2019, only Tulsa educators had been trained to teach the subject, but the Tulsa Race Massacre Commission was working on incorporating the rest of Oklahoma's educators.

Why require it at all? Well, most of the atrocities committed by white people in the US, especially those that implicate any level of government negligence or participation, are commonly avoided in the school system. It's important to know about these sorts of crimes against humanity for a slew of reasons, most of which you already know, for example: "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." – George Santayana

The aftermath of the Tulsa Race Massacre

The immediate aftermath following the massacre could be summed up by saying, "The Black community was forced to fend for themselves," but that doesn't really cover it. Black Tulsans would snap immediately into action, working to rebuild the community of Greenwood with little help, climbing over hurdles put in place to actively hinder the process. The city wanted to relocate the segregated community, but Greenwood was home to the Black citizens who'd been displaced. According to the Zinn Education Project, thousands of Black Tulsans had to endure the winter living in tents.

The fight for Greenwood was intense. The city had put a fire ordinance in place to prevent rebuilding, but Black lawyers fought it and eventually won, according to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Insurance never paid claims for damaged homes, and most relief efforts were blocked or didn't come at all, with the exception of the American Red Cross, which sprang into action while fires were still burning. According to Tulsa World, the Ku Klux Klan capitalized on the aftermath, marching through the streets the following year and winning political offices within the city.

Most of Greenwood would be torn down in the '50s in favor of "urban renewal," according to The Black Wall Street Times. Today, urbanization and gentrification continue to erase much of old Greenwood and the Black history associated with it.