The Untold Truth Of Penny Dreadfuls

Despite the rumors, the English aren't so very different from the rest of us. They want the same things, more or less — food, shelter, love, all that Maslow Hierarchy of Needs stuff, as Simply Psychology lays it out. And even if you aren't achieving some of those levels of need, maybe you want to be entertained. Which isn't really an excuse for bear baiting, as History describes it, but had to have helped popularize Shakespeare during that same era. (Imagine the choice: Shakespeare, or watch a pack of dogs maul a bear, while the bear mauls back? Good times.) Scholars disagree what the literacy rate might have been during the reigns of various Tudor monarchs, but by the end of Queen Victoria's reign, right at the turn of the 20th Century, nearly everyone could read — men and women both, according to the British Literature Wiki at the University of Delaware.

And you'd want to know how to read, for information but also for pleasure, partly because bear baiting was illegal in England as of 1835, says The Independent. (Also cock fighting and dog fighting. Thanks for asking.) Society was enjoying the benefits of the Industrial Revolution (though also the drawbacks, like child factory labor, says the Economic History Association), giving a grateful world less expensive manufactured goods.

Thieves and blackguards and vampires - oh, my!

Among those goods were printed materials: Bibles, of course, and educational tracts, but also entertainment. And just as a large segment of American film goers love a good slasher flick, for cheap books in Victorian England, the gorier, the better.

In America, we called them dime novels. The English called them penny dreadfuls. Encyclopedia Britannica describes them as examples of "an inexpensive novel of violent adventure or crime." Sometimes referred to as "shilling shockers," sometimes "penny bloods," the fictional narratives would come in installments, and the more sensational, the better. They were printed as cheaply as possible, on flimsy paper, and as a result, very few examples survive today, according to the BBC. It's hard to imagine today; think of them as a cross between ultra-violent video games, direct-to-video slasher movies, the most socially irresponsible TV productions of days gone by.

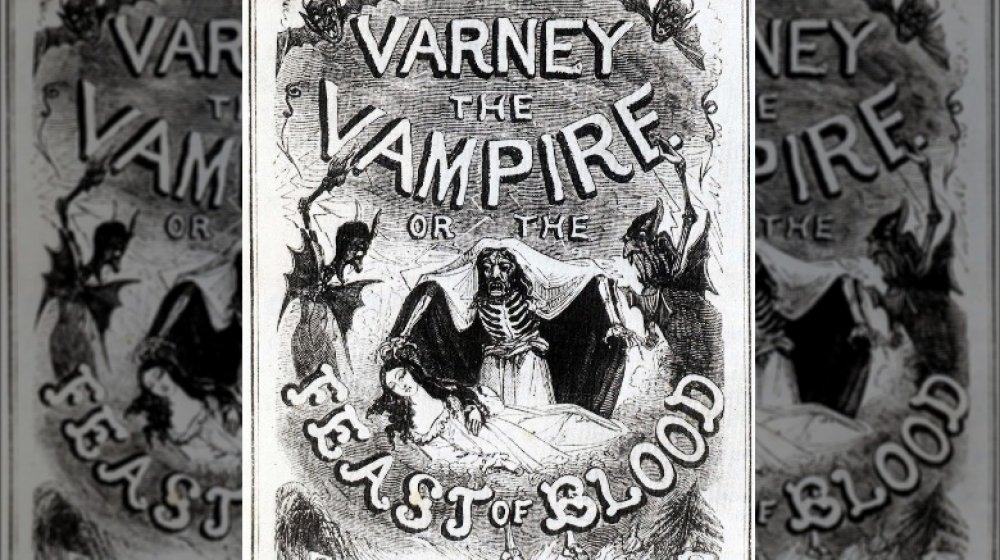

Sometimes the story would be a simple adventure yarn. More frequently, there was moral turpitude involved — plenty of crime — along with plenty of paranormal, and of course, chillers like Varney the Vampire; or, The Feast of Blood. Estimates vary, but some scholars think as many as 100 companies were cranking out the tales.

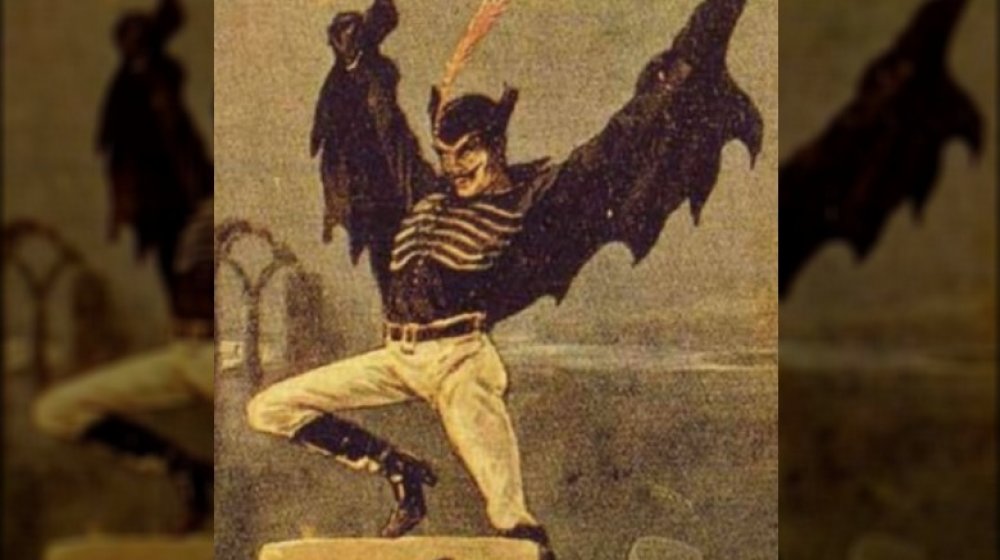

Illustrations were as lurid as the text

Stables of writers paid by the line, some of them juggling more than one series at a time, a business model used later by the publisher of The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew and a host of others. Writing had to be done according to physical specifications, fitting sections of stories into installments 8-16 pages in length.

It was all quite escapist. And a little bit naughty. And a little bit criminal. And illustrated. Plausibility wasn't necessarily the first consideration for the artistic process. (One series killed the same character twice. That might not have been unique, either.) And of course they were robustly condemned by proper folks — penny dreadfuls corrupted the masses, glamorizing criminality and you-know-what (care to take a glance at The Maniac Father; or, the Victim of Seduction? Do you dare?). One critic of the genre, Francis Hitchman, called penny dreadfuls "the literature of rascaldom." There were defenders — even G.K. Chesterton, a philosopher, theologian, and novelist, wrote that "sensational" novels were "the most moral part of modern life. ... (L)iterature that represents our life as dangerous and startling is truer than any literature that represents it as dubious and languid. For life is a fight and is not a conversation."

Tell it to the "men with masks and women with daggers ... heartless gamesters, nefarious roués, foreign princesses," and the rest of the cast, says the British Library. Can't hardly wait until the next installment.