The Craziest American Cowboy Stories You Never Heard In History Class

In his 1996 book, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, author James W. Loewen pointed out that textbooks often gloss over certain events in history. Loewen reasoned that educators often have "a desire to shield children and avoid disharmony," among other things. This is nothing new; even the deaf-blind author and activist, Helen Keller, proposed, "People do not like to think. If one thinks, one must reach conclusions. Conclusions are not always pleasant." As a result, America's educational system falls short of telling us the more interesting aspects of the past.

This is especially true when it comes to the Old West, which is actually so fascinating that admiring story tellers have spewed forth a plethora of folklore and fibs over time, according to Listverse. The real stories of cowboys and other figures of the West have tended to fall to the wayside as more "interesting" stories are told. As History notes, the work of a cowboy was "lonely, sometimes grueling." But don't let that fool you: there are some really great, really crazy stories about American cowboys that are essential to giving us a more well-rounded history of the West. Here are some stories that should have, but didn't, make the books.

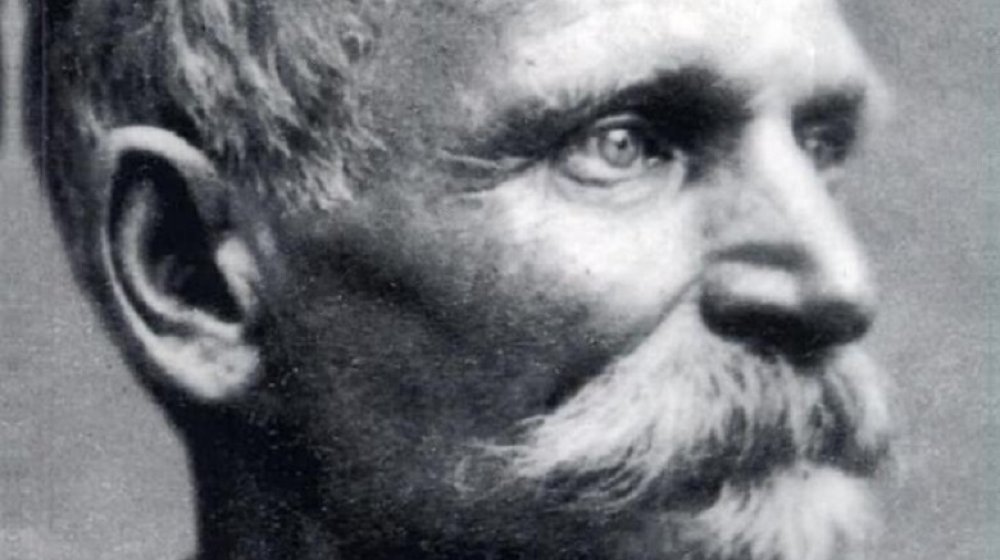

Black Bart, the rhyming robber

In 1875, according to the Black Bart website, John Shine was driving a Wells Fargo coach when he saw a well-dressed man wearing a flour sack on his head. "Please throw down the box!" the man said. Please? From a robber? Still, Shine did as he was told. Indeed, Charles Boles, aka Black Bart, was a gentleman bandit who actually took his nickname from a book, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Bart liked books, as well as poetry, which he began penning and leaving at his crime scenes. "I've labored long and hard for bread," read one rhyme following an 1877 holdup, "For honor, and for riches, But on my corns too long you've tread, You fine-haired sons of b**ches."

Over time, Black Bart pulled an estimated two-dozen heists in the West, according to the Paris Review—always on foot, and never firing his gun. When he could, he left a poem for his victims to remember him by. Two of them survive. When he was finally caught in 1883, he was sentenced to six years in San Quentin, but naturally got off four years later for good behavior. Bart claimed his life of crime was over—until 1888, when a handkerchief at the scene of another robbery was traced to "Boles, an elderly man in San Francisco," according to History. When questioned he said, "I am a gentleman!" There was no denying it was true.

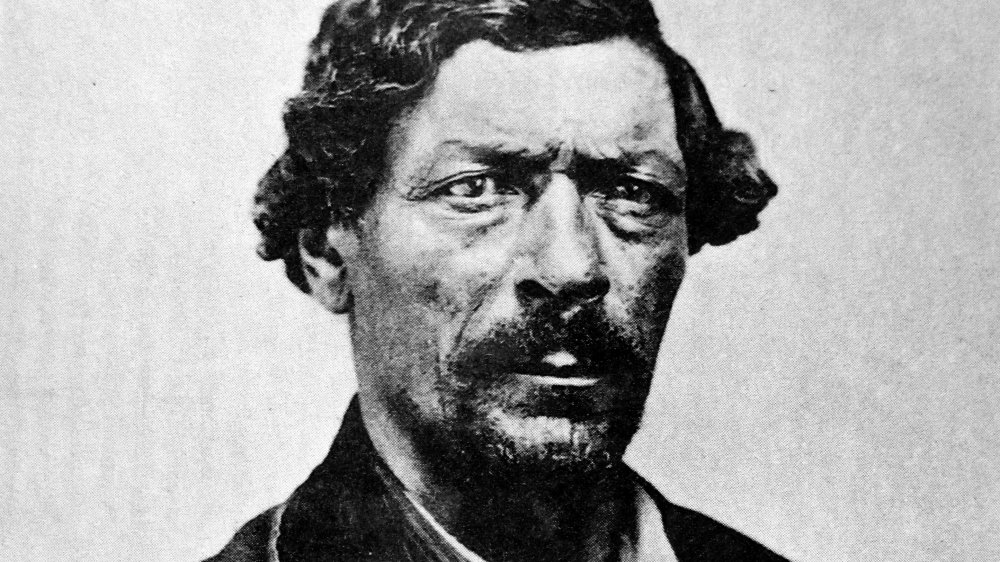

James Beckwourth, the Blowhard Story Teller

Jim Beckwourth was many things: mountain man, fur trapper, Indian fighter and explorer. Although Smithsonian Magazine points out that one in four cowboys in the Old West was black, Beckwourth is one of the few lucky enough to have several biographies written about him. Findagrave explains that Beckwourth was the son of a white officer from the Revolutionary War and one of his slaves. He received schooling in Missouri before coming West with the Rocky Mountain Fur Trading Company during the 1820s. Later he would work for General John C. Fremont and others as a scout, and discovered today's Beckwourth Pass. He also fought in several wars between Anglos and the Native Americans and helped found the early fort at Pueblo, Colorado.

Beckwourth's adventures were exciting enough, but the man couldn't help embellishing them. In his 1856 autobiography, The Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, he claimed he was captured by a Crow tribe, mistaken for the lost son of a chief, and subsequently got to marry the daughter of another chief. Later, he said, he married "Senorita Louise Sandeville." But the lady's name was really Luisa Sandoval, who cast Beckwourth aside for trapper John Brown and lived out her life happily in San Bernardino, California. Admittedly, Beckwourth's exaggerations about his life make for some interesting reading, even if he did tell a whopper or two.

Jack Slade, the Drunken Troublemaker

Ask Virginia Slade, and she would say her husband Jack was intelligent, kind, and devoted. But Virginia also knew that her man was a diehard alcoholic who sometimes killed others for no particular reason when drunk. Even Jack's early years were fraught with violence. Author Jan Murphy states Jack was a bully in school, killed his first man at age 13, was dishonorably discharged from the Mexican-American War, and killed dozens of men. He did have a soft spot for Virginia, whom he met in a dance hall and married in 1857. When the couple managed a stage station (pictured) in Colorado, Jack named it Virginia Dale after his lady.

Jack Slade soon proved himself to be "capable of defying floods, droughts, blizzards, outlaws and hostile Indians," according to Colorado Country Life. But after another drunken spree, he was fired in 1862. The Slades moved to Virginia City, Montana. Jack ran a successful freighting business, opened a dairy, and established a toll road. But his drunken escapades continued. Author Richard Erdoes writes of him tying one on in the local dance halls, sometimes pointing his pistol at the girls. Following one last two-day bender in 1864, 400 fed-up men gathered and strung Jack up at a local corral. Virginia, who rode her horse at breakneck speed from the couple's cabin eight miles away, hoped to save him. But by the time she got there, evil Jack Slade was dead.

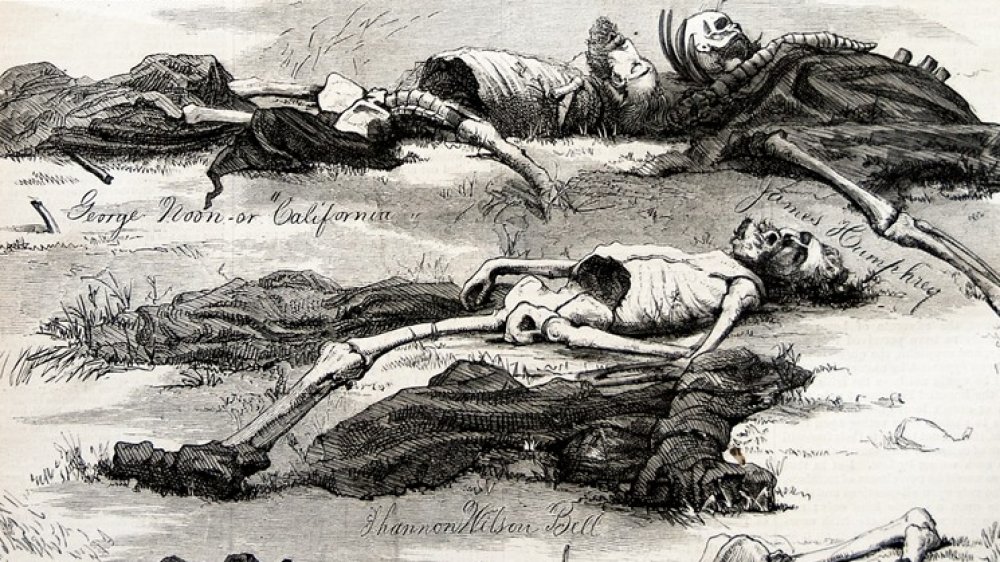

Alferd Packer, the Colorado Cannibal

In the spring of 1874, Alferd Packer stumbled into Colorado's Los Pinos Indian agency with a terrible story. His five fellow prospectors—Shannon Bell, James Humphrey, Frank Miller, George Noon, and Israel Swan—had left him to starve in the wilderness. But Packer looked amazingly healthy. According to All That's Interesting, he also carried a knife belonging to Miller. And, he had a large amount of money on him. Upon further questioning, relates Colorado Virtual Library, Packer admitted that he had come back to camp to find Bell had killed the others and was munching on their flesh. When he came at Packer there was no choice but to kill Bell in self-defense. And then Packer ate the dead himself.

Nobody bought the story. At his murder trial, according to Murdurpedia,the judge cried out, "There were seven Dimmycrats in Hinsdale County and you ate five of them!" Packer managed to escape from jail for nine years but was finally sentenced to the Colorado State Penitentiary. He was paroled in 1901. In 1950, according to Colorado Life Magazine, a gun was found near the massacre site. It wasn't until 1994 that the gun was verified as Packer's. It had three of its five bullets missing, just like Packer said it did when he explained how he shot Bell. Packer was pardoned, and today the University of Colorado at Boulder's cafe is named for him. Just don't order the mystery meat.

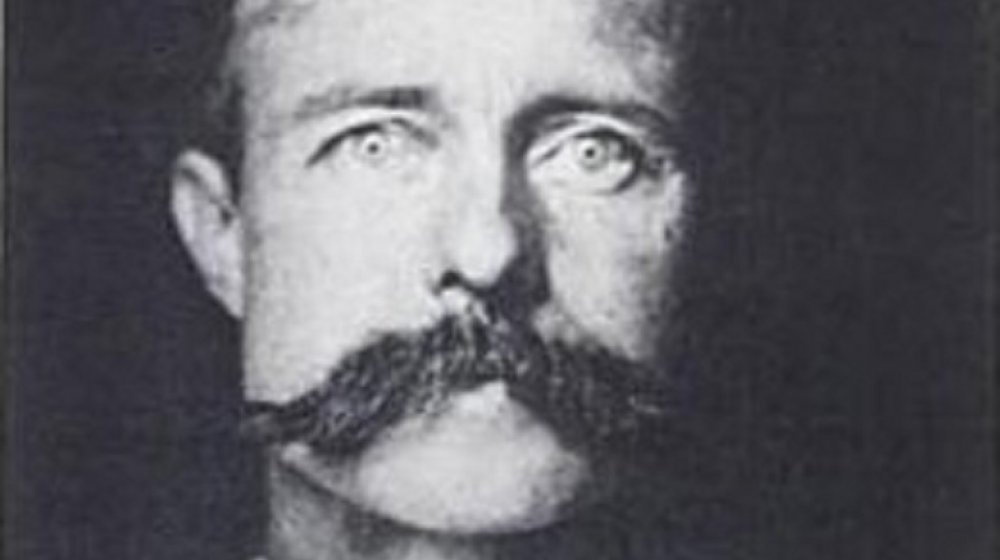

'Buckskin Frank' Leslie, a real lady-killer

Frank Leslie was a noted Indian scout when he first appeared in Tombstone in 1880. Arizona State Historian Marshall Trimble writes that the man was only in town a few months when he shot the husband of Mae Killeen after the man confronted him. Eight days later Leslie married Killeen who, according to the Green Valley News, later divorced him for beating her and forcing her to stand still while he shot her profile along the wall behind her. He also was suspected of several other murders. He did kill Billy Claiborne, who had survived the infamous gunfight at the O.K. Corral in 1881.

After his divorce, Leslie took up with prostitute "Blonde Mollie" Williams. But the two were prone to drinking and fighting until one day, Leslie shot Williams dead in a rage. History verifies that a ranch hand witnessed the murder, and Leslie was sentenced to 25 years in prison at Yuma. He was paroled with the help of another woman, Belle Stowell, who actually dared to marry him in 1896, according to Findagrave. Belle apparently came to her senses, for Leslie was single when the 1920 census taker found him in California. Nobody knows where or when he died, which seems fitting for such a nasty man.

The torrid affair of Clara Dietrich and Ora Chatfield

To say that cousins Clara Dietrich and Ora Chatfield were close is an understatement. The girls were indeed close, in the friendly sense, as children. In 1884, the Aspen Weekly Times in Pitkin County, Colorado noted that they had spent Independence Day visiting friends in Aspen. But according to author Rosemary Fetter, the Denver Times revealed in July of 1889 that there was something disturbing about their relationship. "It was ascertained that [Ora] was madly in love with Miss Dietrich, with whom she was living. The two were torn apart and a warrant was procured in Aspen for the arrest of [Clara] with the intention to have an investigation made as to her sanity."

The girls, who were nieces of the esteemed Leadville city councilman and Colorado State Assembly member I.W. Chatfield, promised to end the relationship. Instead, they carried on with their affair. Newspapers as far away as Georgia reported that the girls "were continually writing each other love letters" and eventually eloped to Denver. Was the relationship simply the stuff of curious young girls? Perhaps, for in 1892 Geneanet confirms that Clara married. She died in 1919. Ora married too, in 1898, but was divorced by 1900. She died in 1936. Today, Chatfield Dam and Chatfield Park in Littleton are named for the girls' uncle.

Cattle Annie and Little Britches

Move over, Teen Magazine. Long before there was such a thing as groupies, Anna "Cattle Annie" McDoulet and Jennie "Little Britches" Stevenson found themselves enamored with the notorious Doolin Gang, which Legends of America identifies as a group of outlaws headed by William Doolin. The gang favored Oklahoma Territory, where they robbed banks and stagecoaches. Enter Cattle Annie and Little Britches, who went in on a horse together during the early 1890s and set out to become members of the club. Along the way, according to Cowgirl Magazine, the teens illegally sold liquor to some Native Americans and Jennie married a man named MidKiff. The also stole cattle, horses, guns, and ammo for the Doolins, alerting them when lawmen were afoot.

In July, the Wichita Daily News in Kansas reported that Jennie Stevenson, who dressed like "a boy tramp hunting work," was arrested for selling illegal hooch in Oklahoma. A month later, according to the Rock Island Argus in Illinois, both Annie and Jennie, "two notorious female outlaws," were arrested again at Pawnee, but not without a fight. Cowgirl Magazine claims the girls were arrested after U.S. Marshal Bill Tilghman and a Deputy Marshal were at the Doolin hideout and Jennie shot at him. However it really happened, the teens were sent to a Massachusetts reform school and were released within three years. Both went respectable and married.

Cowboys and Aliens in Texas

On a morning in 1897, residents of Aurora, Texas were astonished to see some sort of airship cruising the town. The ship "collided with the tower of Judge Proctor's windmill and went to pieces with a terrific explosion." The Dallas Morning News reported that the townspeople found a "badly disfigured" pilot of the crash who was "not of this world." Papers found on the body seemed to be written in hieroglyphics of some kind. A funeral for the dead creature was scheduled for the next day. Was it a hoax? Residents didn't think so, for the funeral took place in the Aurora Cemetery. A marker was made to commemorate the dead pilot.

The story was virtually forgotten until, according to the Houston Chronicle, visitors during the 1970s began tromping all over the cemetery stealing headstones, as well as artifacts from the local museum. When the International UFO Bureau proposed exhuming the body, the group was turned away. "Earthly resident or not," declared resident Karen Tedrow, "they ought to let it rest in peace." Sadly, in 2018, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported the marker had been stolen. A $1,000 reward was offered for its return. A few weeks later, the Dallas Morning News supposed that S. E. Haydon, author of the original article, simply wrote it to "drum up interest in tiny Aurora and save his town." The marker, meanwhile, remains missing.

Frank Wattron's Uncouth Invitation

In 1899 a disgruntled Arizona railroad employee, George Smiley, shot his foreman, P. McSweeney, to death over back pay. Smiley made history as the first man to hang in Holbrook. Sheriff Frank Wattron, anxious to show something for himself, sent out 50 fancy invitations reading, "You are hereby cordially invited to attend the hanging of one GEORGE SMILEY, MURDERER. His soul will be swung into eternity on Dec. 8, 1899, at 2 o'clock p.m., sharp. Latest improved methods in the art of scientific strangulation will be employed and everything possible will be done to make the proceedings cheerful and the execution a success."

News off the tasteless invite drifted as far as the White House, where President William McKinley demanded it be changed. A second, rather sarcastic invitation was issued by Wattron: "With feelings of profound sorrow and regret, I hereby invite you to attend and witness the private, decent and humane execution of a human being: name, George Smiley, crime, murder. The said George Smiley will be executed on January 8, 1900, at 2 o'clock p.m. You are expected to deport yourself in a respectful manner, and any 'flippant' or 'unseemly' language or conduct on your part will not be allowed. Conduct on anyone's part, bordering on ribaldry and tending to mar the solemnity of the occasion will not be tolerated." Navajo County verifies that Smiley finally swung into eternity on January 8, 1900.

Little Joe Monahan, the woman who dressed as man

In 1867, a cowboy calling himself Joe Monahan took up residence in Ruby City, Idaho. He was an odd little man with a high-pitched voice, mostly keeping to himself while raising small stock, selling milk, shepherding, and rounding up cattle. He was so short that they nicknamed him "Little Joe." It wasn't that Little Joe was unfriendly, but he had no use for dance halls and saloons, and preferred sleeping outside to bunking with other cowboys. Around the O verifies that some folks had an inkling that Joe wasn't what he said he was; in the 1880 census he was recorded as male, but the census taker added a penciled note: "Doubtful Sex." Still, he was well liked and respected by other cowboys.

Joe Monahan lived in Idaho for some 40 years in obscurity, except for once when he was encouraged to show off his fine horsemanship on film for Andrew Whaylen's Vitagraph Film Company. In the winter of 1904, he was ill when he died at the home of friends in Oregon. Only then, according to writer Hannelore Sudermann, was it discovered that Joe was actually a woman. Letters in his cabin revealed (s)he was from New York and disowned by their family after having a child out of wedlock. Joe Monahan rests in peace at Rockville Cemetery in Oregon. In 1993, their story was told in the movie The Ballad of Little Jo.

One last drink for John Shaw

On a night in 1905, John Shaw and William Smith wandered into the Wigwam Saloon in Winslow, Arizona. The men ordered shots of whiskey, which were set on the bar before them. Suddenly, however, they pulled their guns, relieving the patrons of hundreds of silver dollars. They fled, but Sheriff Chet Houck and Deputy Sheriff Pete Pemberton found a trail of stolen loot leading to the train tracks. They were able to track the outlaws to Canyon Diablo, once a hell-raising town in the Arizona desert. Shots were fired, injuring Smith and killing Shaw. The officers buried him beside the train tracks.

The next night, some cowboys from the Hashknife outfit were discussing the robbery when it occurred to them that Shaw never drank his shot. Inspired by the alcohol they drank, the men—including Pemberton—rode out to Canyon Diablo and dug up Shaw's body. Someone had thought to bring a camera, and took photos of the body in the grave, as well as pics of the men holding Shaw up with an eerie smile on his lifeless face. He was duly given his drink and reburied. The men must have seemed like ghouls, but witness Jack LeBarron later explained that "it seemed to us that giving him a drink for his last trail was proper."

Elmer McCurdy, would-be outlaw to funhouse dummy

In December of 1976, a film crew from Universal Studios was filming an episode of the Six Million Dollar Man at Nu-Pike Amusement Park in Long Beach, California. When a worker on the set grasped one of the fun house dummies to move it, its arm broke off. To everyone's horror, a human bone was clearly visible. It took a while to figure out the body's identification. Ripley's claims that a 1924 penny and tickets to the Museum of Crime were lodged in the corpse's mouth, enabling investigators to trace at least some of its past.

Research finally revealed the body as Elmer McCurdy, was one of two train robbers who was killed in 1911 in Oklahoma. Officers, reported the Guthrie Daily Leader, said "they have rid the city of the leader of the gang." But McCurdy ended up hanging around. The undertaker kept the body in his room, charging a nickel to see it. When two men claiming McCurdy was their brother showed up in 1915, the undertaker turned over the corpse. But the men were actually carnival promoters, and McCurdy found new "life" as an attraction that was forgotten about in time. Today he is back in Guthrie, where he rests at last in Summit View Cemetery.