The Most Important LGBTQ Court Cases In U.S. History

The history of LGBTQ rights in the United States is insanely complicated — so complicated that, well, let's put it this way: Five years after the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriage bans were unconstitutional, some states were still trying to get bans removed from the law books. How is that even possible? It's because, NBC News says, of the existence of "mini-DOMAs," or state-level versions of the Defense of Marriage Act.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. For decades, men and women have been fighting for the right to be with the person they love, and it has been a long, difficult fight.

While many LGBTQ individuals have faced their own personal struggles, some have taken the fight for equality out from behind closed doors and put it right on the national stage. Some have won their cases and advanced the hopes — and rights — of the LGBTQ community. Others have lost ... but those losses are important, too, underscoring the need to keep fighting for still-elusive equality. Let's talk about those court cases, and the brave people who took the fight to the national level.

The original same-sex marriage case

In 1970, Jack Baker and James Michael McConnell applied for a marriage license. They were denied, and they sued. When the case went before the Minnesota Supreme Court, The New York Times says that one of the judges was so disgusted that he turned his chair around and wouldn't even look at them. The men claimed the denial was an infringement on their civil rights and privacy, while the court ruled that marriage was "a union of man and woman, [...] as old as the Book of Genesis."

The case, Baker v. Nelson, went all the way to the US Supreme Court, and their appeal was dismissed with a one-line explanation: There was no "substantial federal question." Technically, that means they lost their appeal, but decades later, their case was used as a precedent, leading to the issue going before the Supreme Court again.

But the couple's story gets even better than court cases. Baker — who enrolled in law school after promising to find a way for them to get married — started out by having McConnell legally adopt him, which gave them inheritance rights. Then, he changed his name to Pat Lyn McConnell, and when they applied for a marriage license with the gender-neutral name, it was approved. They married on September 3, 1971. When the issue of gay marriage came up in court again decades later, they were still happily married.

He never pretended he was firing me for any other reason.

Vandy Beth Glenn is a transgender woman who was transitioning in 2007. She was working as a legislative editor for the Georgia General Assembly at the time, and when she told her boss that she was transitioning, well ... "Mr. Brumby told me that people would think I was immoral," she told ABC News. "He told me I would make other people uncomfortable, just by being myself. He told me that my transition was unacceptable. And over and over, he told me it was inappropriate." Then, she was fired.

Glenn — along with the advocacy group Lambda Legal — went to court. She won in district court, and when her boss appealed, she won again. The case, she wrote for The New York Times, became a precedent for how the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission responds to cases where transgender workers are discriminated against. She wrote, "We want no 'special rights' or preferential treatment; we only want to live our lives..."

Finally, on June 15, 2020, the Supreme Court upheld a ruling relevant to Glenn's case: The Civil Rights Act of 1964, they confirmed, does extend to protecting individuals from discrimination based on their sexual orientation and/or transgender status (via NBC News).

Should same-sex couples be allowed to adopt?

In 2004, Frank Martin McGill and his partner started fostering two half-brothers, and in 2008, they decided that they wanted to officially adopt them. Unfortunately, they lived in a state — Florida — that still had a ban on gay or lesbian adults adopting children. While Reuters says that Florida was the only state to still have the law on the books in black-and-white terms, other states, like Mississippi and Utah, blocked same-sex couples from adopting in different ways (per The New York Times). Then, along came McGill and his partner.

The boys they took into their care had been removed from their parents, who had been raising them along with their crack habit. The elder was just four years old, and the younger only four months. Both were suffering from various medical problems, and the older boy had yet to speak. Under the care of McGill and his partner, they "were thriving," and the courts saw it, too, issuing a 53-page verdict that said in no uncertain terms "that gay people and heterosexuals make equally good parents. [...] It is clear that sexual orientation is not a predictor of a person's ability to parent."

McGill called it a major victory, not just for his family but for the hundreds of children just waiting to be adopted.

Does genetics afford some players a competitive edge in sports?

In the early '70s, Richard Raskind was a New York ophthalmologist who played a few times in the men's draw at the US Open, even ranking 13th nationally at one point. Then, in 1975 — after years of depression and fighting suicidal thoughts — Raskind had sexual reassignment surgery.

Renee Richards moved to California and started over. That included tennis, and after it was announced that she won the 1976 La Jolla Tennis Tournament, word got out that the same person had previously competed as a man. By the time Richards was ready to compete in the Mutual Benefit Life Open, 25 of the 32 competitors dropped out, citing an unfair playing field. According to Vice, that's when the United States Tennis Association announced a gender verification test: The Barr test would confirm the number of X chromosomes a competitor had.

That's when Richards went to court. Richards v. United States Tennis Association argued that the chromosome test was discriminatory and violated the 14th Amendment and the New York State Human Rights Law. The courts ruled in her favor, saying, in part: "When an individual [...] finds it necessary for his own mental sanity to undergo a sex reassignment, [...] this person is now female." Richards entered into the US Open as a woman ... and lost.

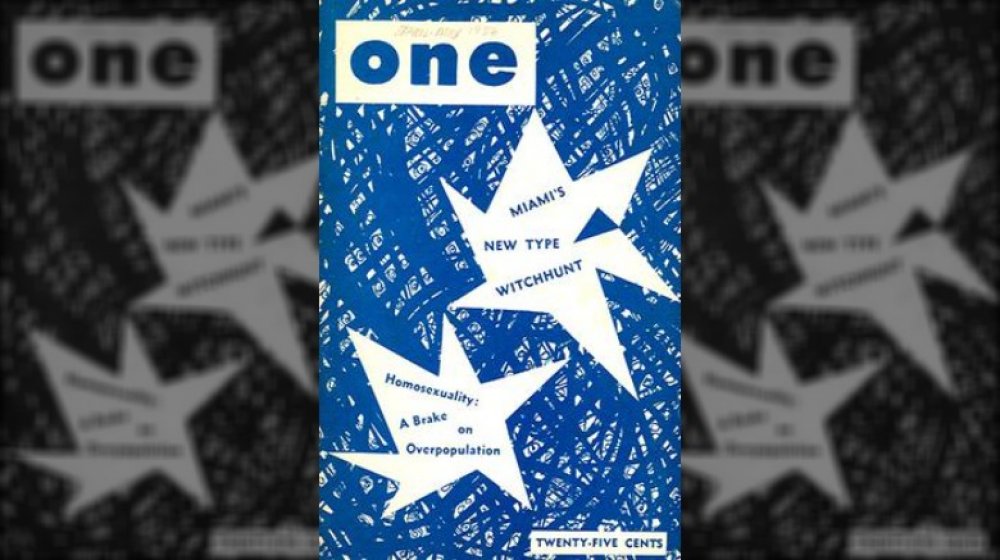

LGBTQ literature is not obscene

Way back in ye olden days of 1953, writers in a tiny Los Angeles office launched a magazine called ONE. They billed it as the "magazine for homosexuals," and according to the Los Angeles Times, the pages were filled with editorials, articles, and stories — there were no suggestive photos, no X-rated ads ... nothing of the sort. Still, the postmaster of the city ordered all postal authorities to seize copies of the magazine (via MTSU), and the publishers were informed that it was "obscene, lewd, lascivious, and filthy," and couldn't be sent through the Postal Service.

Enter Eric Julber, an attorney who was just starting out and agreed to represent the magazine pro bono. His reasoning? "They were not running a night club. They were writing a [...] very conservative magazine. It was just the subject matter — homosexuality — that made it 'obscene.'"

Julber filed a lawsuit claiming discrimination, and he lost repeatedly, even though, as he pointed out, publications promoting polygamy and nudity were A-okay. He didn't give up, and in 1958, the case went to the Supreme Court, which reversed the decision of all the lower courts. Based heavily on a precedent set in an earlier case, which ruled that, "Sex and obscenity are not synonymous," it was decided that ONE was not obscene, and by extension, LGBTQ literature is not automatically obscene, either.

Coy Mathis' right to use the restroom

Rolling Stone says that Coy Mathis was just three years old when he had a serious conversation with his mother: He wanted to know, "When am I going to get my girl parts?"

When Coy started school and his parents checked the box next to "boy," that's when things really started to get difficult. For a while, they allowed pink hair bows and dresses at home but insisted on jeans and sneakers in school. It didn't work — mother Kathryn Mathis said, "We were thinking, 'If we give you a safe space to be who you are, that's our way of being supportive.' But we were really sending the opposite message: 'It's not safe, but we'll give you a place to hide.'" With support from parents, teachers, and school staffers, Coy happily became "she" ... until first grade, when gender-neutral bathrooms were no longer available, and students had two choices: boys' and girls'. Coy was told she still fell into the boys' category.

The Mathis family filed a complaint with the Colorado Division of Civil Rights, and per CNN, the verdict was in favor of Coy. The state ruled that upholding the ban "creates an environment that is objectively and subjectively hostile, intimidating, or offensive," and while it was the first ruling of its kind in the country, it was also noted that a precedent had already been set when the idea of "separate but equal" facilities was deemed unconstitutional.

Can the government control the relationships of consenting adults?

In 1982, Michael Hardwick, who was bartending at a gay pub in Georgia, threw a beer bottle in the garbage and was cited for drinking in public. When he didn't show up in court, officers headed to his apartment to carry out an arrest warrant. A guest opened the door, and they went inside. That's when they saw him — in his bedroom — engaging in oral sex with another man. Both were arrested on sodomy charges.

The charges, Slate says, would have stood even if the act had been between a man and a woman, but Hardwick agreed to become the face of the movement declaring sodomy laws unconstitutional. His case, Bowers v. Hardwick, was originally dismissed, but he won on appeal based on the fact that his privacy had been violated. But when it went to the Supreme Court, it wasn't a matter of privacy — it was a matter of whether or not "the Federal Constitution confers a fundamental right upon homosexuals to engage in sodomy." The court ruled that it didn't, and the case turned into a major setback on the road to equal rights, in spite of the outcry that followed.

It would be another 17 years before that verdict would be overturned in another case, Lawrence v. Texas (via Georgetown Law). There, in 2003, the Supreme Court ruled that what happened between two consenting adults behind closed doors was their business, and only their business.

Bullying is bullying ... no matter what the reason

For Jamie Nabozny, school was very, very difficult. By the time he was in junior high, he was bullied on a regular basis. The abuse happened even right in the middle of class: "I was in a science classroom, and sitting next to two of the boys who were my biggest harassers, and they started groping me and grabbing me [...] and pretended like they were raping me in front of the entire class." The teacher was out of the classroom, so Nabozny went to the principal, who told him he didn't have an appointment and "I don't have anything to say to you."

After a beating that sent him to the hospital with a torn stomach and ruptured spleen, Nabozny ran away to Minneapolis. Then, in 1995, with the help of the Gay and Lesbian Community Action Council, he filed a lawsuit against his former school.

Nabozny won — not against the district (which had laws on the books that were supposed to protect kids against sexual discrimination) but against the principals who had looked the other way. While he's said (via NYSUT) that the case sent a powerful message that it's not okay to ignore kids who are getting bullied, he also acknowledges that the country has a long way to go: Nabozny continues to tell his story (via Tolerance) in hopes of letting other LGBTQ kids know they're not alone, and they do have rights.

The constitutional right to marry

In 2015, the Supreme Court confirmed a national, constitutional right to marry. It was a massive win for LGBTQ equality, with Justice Anthony Kennedy writing about (via The New Yorker) "the abiding connection between marriage and liberty." The decision was so monumental that it's worth taking a look at the absolute heartbreak that brought the US to that moment in the first place: the story of Jim Obergefell (pictured) and his husband, John Arthur.

Arthur and Obergefell were partners for 21 years, and in 2013, they married. Only 100 days later, Arthur passed away from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. When it came time to issue the death certificate, Ohio refused to include Obergefell's name as the surviving spouse. So, The Washington Post says, he went to court.

While the court confirmed their marriage — and the right for same-sex couples across the country to marry — the dissent both inside and outside the courtroom remained loud. To those dissenters, Obergefell had this to say: "I ask that they think about the people they love: [...] If one of those people came out as LBGT, that person is still the same person you know and care about. Nothing has changed. Wouldn't you want the people you care about to be able to live life and enjoy the same rights and protections that you do? That's what this fight is about. [...] Every American should be treated equally..."

Because I am a loyal scout.

In 1990, James Dale was going into his junior year at Rutgers, and he'd been in the Scouts since he was eight. He found a direction in life and learned how to accept himself for who he was ... and then he got a letter. It read (via The Washington Post): "The grounds for this membership revocation are the standards for leadership established by the Boy Scouts of America, which specifically forbid membership to homosexuals."

Dale later wrote that it was the sense of integrity and community that the Scouts had taught him that made him realize he couldn't stand for it — not just for his sake but for others who had found an accepting home within the Boy Scouts. So, supported by the same Scoutmaster who had made him an Eagle Scout, he went to court.

He won in the New Jersey Supreme Court (which said, "The human price of this bigotry has been enormous,"), but on June 28, 2000, he lost in the US Supreme Court. The fight wasn't over, though, and in 2013, the Scouts voted to include gay members. Two years later, they voted to remove a ban on gay leaders, and in 2017, they opened their doors to transgender boys (via The Washington Post), in spite of the fact that some longtime sponsors — like the Mormon Church — were ending their association with the Boy Scouts.

When it takes a court case to get justice for a hate crime

When Brandon Teena left his hometown of Lincoln, Nebraska, he was hoping for a fresh start. According to The Atlantic, things started out that way for him in Falls City. He started dating and found friends, but when those friends found out that he was biologically female, what happened next was one of the most horrific hate crimes in recent history.

John Lotter and Marvin Nissen became obsessed with the idea that Brandon was female, and on Christmas Eve 1993, they first stripped and then raped him. Brandon went to the police, and the questioning that followed was so unthinkable that Kimberly Peirce, director of Boys Don't Cry, a movie based on the events, referred to it as "a third rape." The sheriff who interviewed Brandon, Charles Laux, didn't arrest Lotter and Nissen — despite the fact that the story was confirmed by a hospital report, evidence was collected, and it was well-known that they'd threatened retaliation if the police were involved.

Brandon hid out at a friend's house, where Justia says he and two others were murdered. Brandon's mother sued, and it was found that the sheriff's office was negligent in failing to protect Brandon from known threats. Now, law enforcement across the country has connections to resources that help ensure that victims have a safe place to go — where those who would hurt them can't find them.

Can care be denied to patients based on their HIV status?

When Sidney Abbott went to the dentist, she was up-front with the fact that she was HIV-positive. When she needed to have a cavity filled, her dentist refused to do it in-office due to a perceived safety risk but said he would treat her in a hospital — provided she paid all the costs.

Abbott took him to court, saying that the action was in direct violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the verdict was a huge deal. At the heart of the matter was the question of whether or not asymptomatic HIV could be considered a disability, and the court ruled that yes, it could. Why? Because it interferes with and impairs the function of some of the body's systems, and it meets the other criteria, too: It "substantially limits [a] major life activit[y]."

According to Gordon Feinblatt LLC, Abbott argued that the life activity her HIV status influenced is her ability to have children, which the court accepted. They also ruled that filling her cavity presented no "direct threat" to either the dentist or his staff, and that's a huge deal: It set a precedent that individuals with HIV are protected by the ADA.