Forgotten African Americans You Never Learned About In School

Grab almost any standardized grade school or high school textbook, and flip through the pages. Notice anything? The famous, world-changing figures most learn about in school, well, they all have something in common, don't they?

Now, think back to the African Americans you learned about. Rosa Parks, probably, although you were only taught half of her story (and most of it was incomplete at best). Martin Luther King, Jr., no doubt. Harriet Tubman. And... that might be about it. And that's just wrong. Take a look back through history — real history, not the stuff you learn in school — and you'll find tons of brilliant and brave innovators who shaped the world as we know it today... then promptly fell from the pages of the textbooks, for one reason or another. Let's rectify that, at least for as many people as we can.

All of these? They have a few things in common, too: they're black, they're not remembered as they should be, and the world would look very different without their contributions. So let's start remembering.

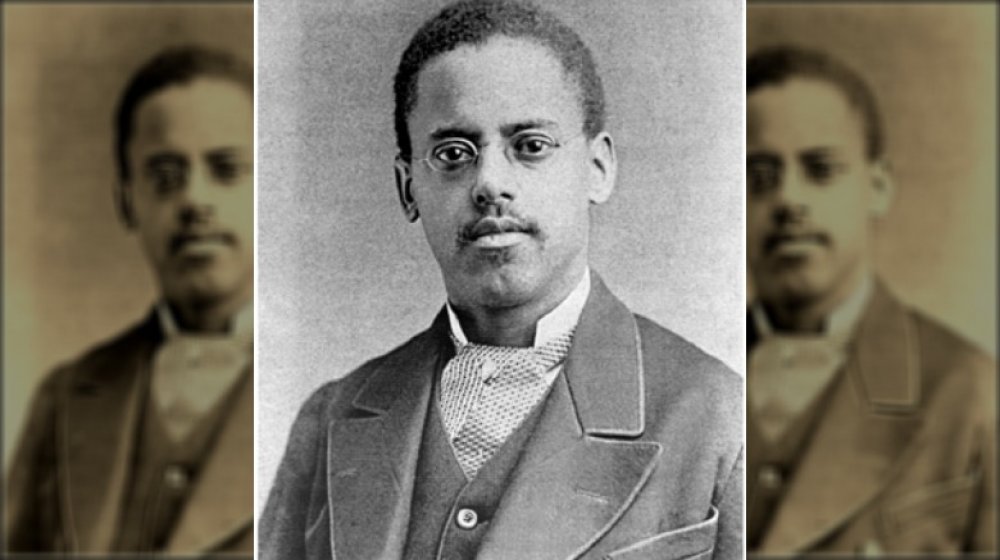

Lewis Howard Latimer: Let there be light

Lewis Howard Latimer was born in 1848, six years after his parents had run away from a plantation in Virginia and the man who owned them. In an attempt to ease the burden on his mother, he joined the Navy when he was 16, and after his honorable discharge, he went to work as an office boy at a patent law firm. According to the Smithsonian, Latimer taught himself mechanical drawing and the firm was so impressed that he was promoted to draftsman. It was there that he met Alexander Graham Bell, who was also impressed — and, he asked Latimer to take care of the blueprints and applications for his patent on the telephone: they beat a rival submission by just a few hours.

From there, Latimer moved on to the US Electric Lighting Company, where he started working in a whole new field. He was there for just four years, before he was headhunted by an even bigger name: Thomas Edison. Edison put him in charge of managing his patents, as well as protecting them from copyright infringement.

And this is also about the time where his scientific know-how came into play. Edison's original light bulb had a paper filament which, not surprisingly, didn't last long. It was Howard Latimer who invented the carbon filament, patented it, wrote the first book on electric lighting, then oversaw the illumination of London, New York City, Montreal, and Philadelphia (via Lemelson-MIT).

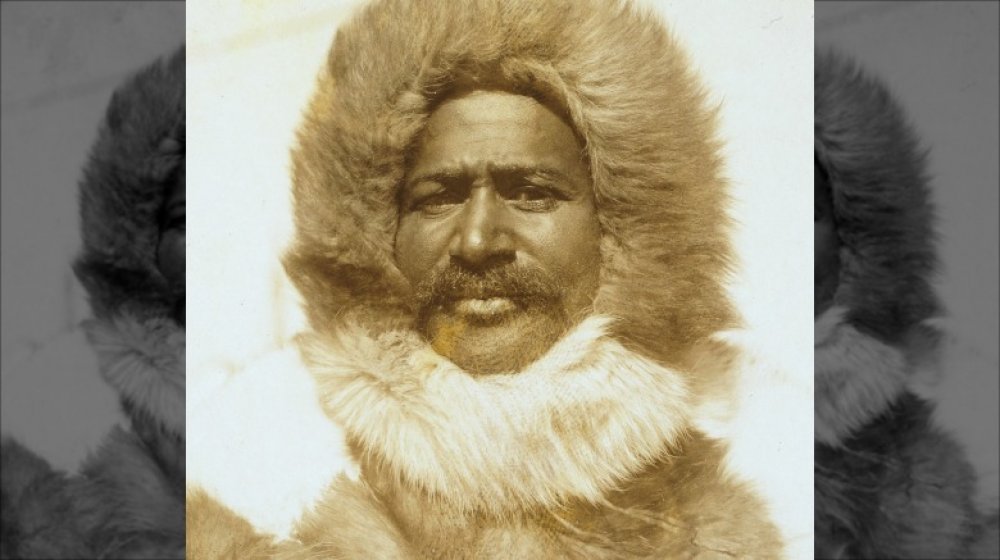

Matthew Henson: First to the top of the world

The stories of Arctic exploration are nothing short of extraordinary, and a huge part of our advancements in making it to the North Pole came courtesy of an explorer that history has largely forgotten. Matthew Henson was born in 1866, and at 12-years-old, he got on board a sailing ship as a cabin boy. For six years, they sailed all around the world, from the East Coast of the US to the African coast to the seas of Asia.

After the death of the captain, Henson got a job in a Washington, D.C. shop — and that's where National Geographic says he met Robert Peary, a naval officer just back from Greenland. Peary hired Henson as a valet, but after their first expedition through Central America, they were fast friends. By 1891, Peary was embarking on his expedition to map the northernmost reaches of the world, and he wanted Henson with him. It's no wonder — Henson was a carpenter, a craftsman, a hunter and fisherman, and accomplished dog-sledder. He was also just a nice guy — the Inuit called him "Matthew the Kind One."

It wasn't until 1909 that they finally reached the North Pole, and while just what happened varies by the telling, Matthew Henson's version is that he overshot the North Pole, backtracked, and — seeing his footprints in the snow — realized he was the first person to stand at the top of the world.

Marie Van Brittan Brown: The reason your family feels safe

Born in Queens, New York, in 1922, Marie Van Brittan Brown would take her circumstances and change the world. Brown and her husband lived in a not-so-great area, and her job as a nurse and his as an electronics technician meant that a lot of the time, one or the other was home alone. Crime was high, police response times were slow, and Brown decided that if she had to be home alone, she was going to be as safe as she could.

So, she developed a surveillance system unlike anything anyone had seen before. There were three peepholes in the door at varying heights, and a camera that could be adjusted to look through any peephole. The camera would wirelessly transmit images to a portable monitor, and once the homeowner realized who was at the door, they could either push a button to call police, or unlock the door with a remote. A two-way communication system was included, too.

BlackPast says that they filed for a patent for their "Home Security System Utilizing Television Surveillance" on August 1, 1966. Brown's system is still in use in smaller homes, apartments, and businesses, and their patent has been referenced more than a dozen times — and well into the 21st century.

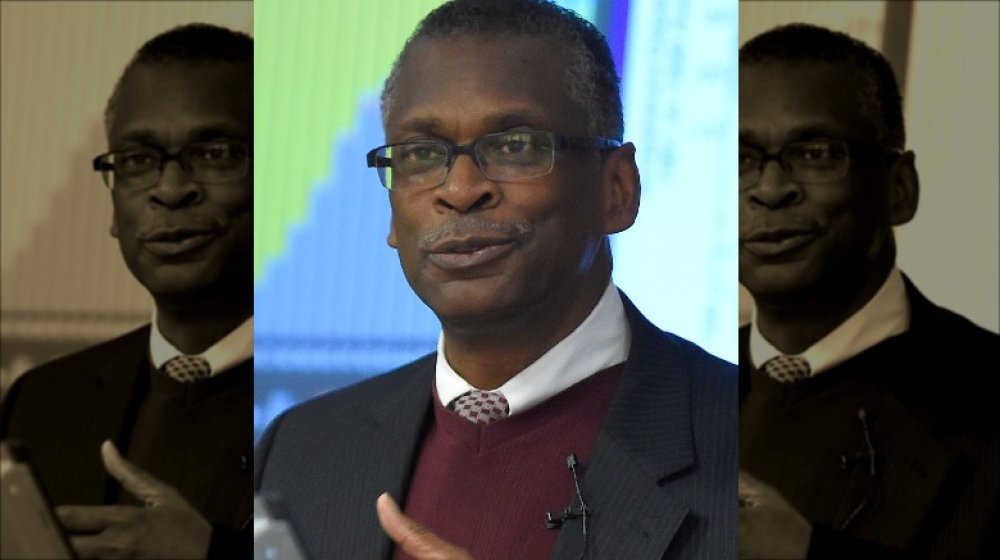

Lonnie Johnson: Super brilliant. Super fun!

Lonnie Johnson found his calling in 1968, when he headed to the University of Alabama to represent his high school in a science fair. Using scraps from a junkyard, he pieced together an air-compressed robot he called Linex — and, in spite of winning first place, those from the university hardly acknowledged him... the only black student competing.

Nevertheless, he went on to earn degrees in mechanical engineering and nuclear engineering, and over the course of his career, he's worked as a researcher at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, then at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The Smithsonian says that his work on the Galileo mission to Jupiter was invaluable, and afterwards, he went on to be an Advanced Space Systems Requirements Officer at Edwards Air Force Base.

That's the literal rocket science covered, now here's the fun. Johnson told the BBC that it wasn't long after he settled into his home in Omaha, Nebraska (amid his work on the B-2 stealth bomber) that he started messing about with making water guns. When he took a prototype to an Air Force picnic and a superior officer asked him if it worked, he literally shot the man in the face. The picnic turned into a massive water fight, and that prototype? It became the Super Soaker, and he used the profits to buy his own scientific research facility and fill it with staff.

Jane Bolin: America's first black, female judge

America's first black, female judge took her seat a long time ago: Jane Bolin was appointed by New York City's Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia in 1939. And that was after being the first black woman to graduate from Yale Law School, says The New York Times, at a time when she was one of three women in the class, and the only black student. Southerners, she later said, enjoyed letting the doors slam on her.

She retired in 1979, and those 40 years were filled with changes to the country's legislation — and they all stemmed from a statement she made just after being sworn in, promising to display "a broad sympathy for human suffering."

What changes did she make? For starters, she led the movement that changed the way childcare agencies decided what children to accept into their programs. Bolin made sure that if the agencies received public funding, they could no longer base their choices on the race or religion of the children in need. She also ended another racially-biased practice: the long-standing habit of assigning probation officers based on race. She went a long, long way to showing other judges how it's done: since many of her cases involved children, she didn't wear robes in order to make children less frightened of the whole process, and when she retired, she was lauded as a singular role model.

Percy Lavon Julian: Making affordable medicines possible

Steroids are used in the treatment of countless conditions, and if you or anyone you know has ever suffered from things like glaucoma, you know how important access to these medicines can be. Well, you can thank an often-overlooked chemist named Percy Lavon Julian for making them readily available.

The Alabama-born grandson of slaves, Julian enrolled in DePauw University to take high school and college courses together. A few years of hard work later, and it was on to Harvard and the University of Vienna, where he did his doctoral work on the chemistry of medicinal plants.

According to the Science History Institute, chemists had been extracting steroidal compounds from animal tissues since the 1930s, but it was insanely expensive. It wasn't until Julian returned to the US and started researching that anyone had synthesized steroids from plants. That first compound he synthesized was physostigmine, and it's used to treat glaucoma. He also figured out how to mass produce progesterone from soybeans (which is used in the prevention of miscarriages), and then both cortisone and hydrocortisone (which are used in the treatment of arthritis) — allowing for a massive improvement in the quality of life for millions.

Bessie Coleman: The pilot who didn't take 'no' for an answer

In 1919, Bessie Coleman was working as a manicurist on Chicago's South Side when her brother — a World War I veteran — started teasing her about her job. He'd just come back from Europe, and women there had many more opportunities. They could even fly airplanes, he laughed!

Coleman was instantly determined, but there was a problem: no pilots in the US would give a black woman flying lessons. So, she started learning French as she saved up for her trip to France.

Which she absolutely made. According to The New York Times, she left the US on November 20, 1920, and enrolled in a flight school in the Somme. By the end of the seven-month course (during which she saw the death of a fellow student), she earned her pilot's license, the first black woman to do so. It was 1921, and soon, she was flying all over the US — and doing things like walking on the wings while in mid-flight. After only a few years of performing and inspiring others to fly, too, she was killed in a tragic accident. She and her mechanic were flying at 3,500 feet when their craft suddenly went into a dive and flipped upside down at 500 feet. She fell and was killed on impact.

Waverly Woodson and the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion

Look at pictures of the beaches on D-Day, and you'll notice something odd-looking: a series of oval-shaped craft floating above the ground troops. Those aren't planes or blimps, they're balloons — and according to the Smithsonian's Air and Space Museum, they were extremely important.

They were towed ashore by the men of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion (which CBS notes was the only all-black combat unit to participate in D-Day), who had spent weeks learning how to camouflage and repair the balloons, along with filling them with highly flammable hydrogen gas. They were dispatched at Omaha and Utah, tasked with getting the balloons in place to protect ground troops from aerial Axis attacks. Dozens of balloons were lofted, shot down, and replaced over the course of the invasion, protecting countless ground troops and allowing invaluable supplies to be offloaded. The 320th helped with that part, too, and as for their medic, Waverly Woodson? He was saving lives.

Woodson disembarked on Omaha Beach — a shell hit his landing craft, killed the man next to him, and peppered him with so much shrapnel he'd thought he was dead. He wasn't — and he spent the next 30 hours tending the wounded. According to History, he's credited with treating around 200 soldiers before collapsing; he was treated on a nearby hospital ship, and was back on the beach just a few days later. He never received the Medal of Honor.

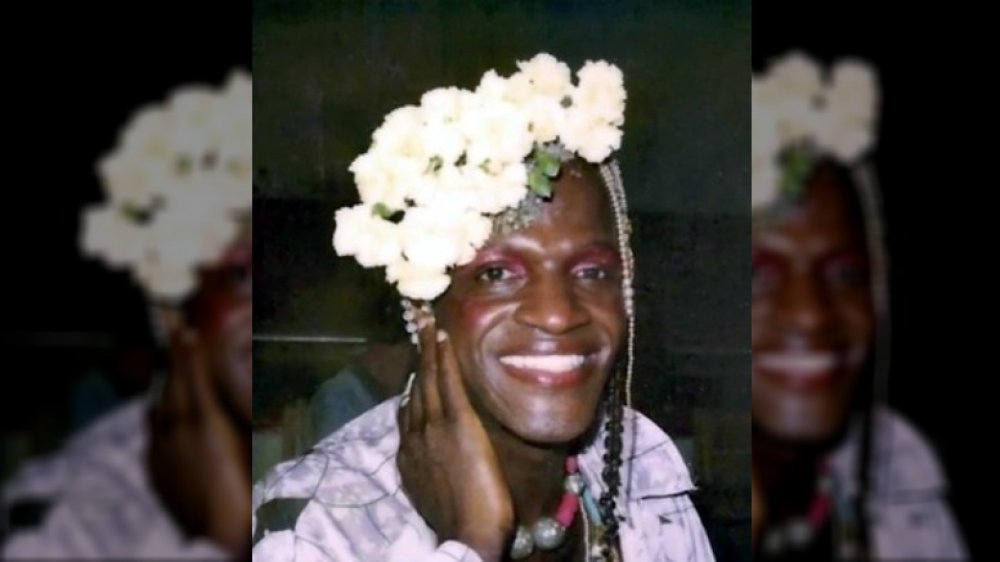

Marsha P. Johnson: Transgender activist and crusader

Marsha P. Johnson told people the "P." stood for "Pay it no mind," and when asked, she'd describe herself (via CNN) as "Nobody, from Nowheresville." That's absolutely not true — she was, for two and a half decades, at the forefront of New York City's gay liberation movement. According to The New York Times, Johnson moved from New Jersey, to NYC with just $15, a bag of clothes, and a powerful mantra: "Don't let anybody tell you what to do, be who you want to be." She didn't just say that, either — she worked tirelessly to advocate for homeless LGBTQ youth and those affected by HIV/AIDS.

It truly started at the Stonewall Uprising — when the dust settled, Johnson and her friend Sylvia Rivera were at the forefront of what came afterwards — including the organization of the first gay pride parade on the anniversary of the protests. She and Rivera went on to found the first LGBT youth shelter on the continent, which along with Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, or STAR, provided housing for the city's homeless youth — giving those who had been shunned by their families not only a place to stay, but a place where they were accepted.

Johnson died in 1992: her body was recovered from the Hudson River, and it was eventually classified as "drowning from undetermined causes." In 2019, it was announced she and Rivera would be the subjects of two of the world's first statues to transgender people.

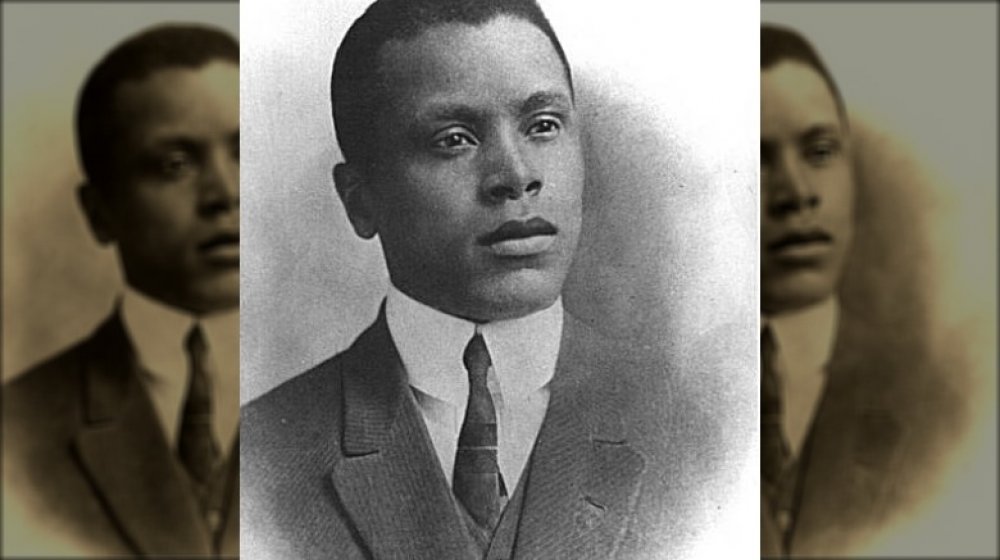

Oscar Micheaux: Documenting racial inequality, one movie at a time

For as long as film has been around, there's been mainstream and outsider. According to The New York Times, Oscar Micheaux was always an outsider, documenting racial inequality and the struggles of minorities in the US since the beginning of his career... in 1919.

Between 1919 and 1948, Micheaux wrote, produced, and directed 44 feature films. And it was an odd journey — he started out as a Pullman porter on the railway, which he gave up to move to South Dakota and become a homesteader. After suffering several family tragedies, he turned to reading then writing to cope — and it was a fictionalized version of his memoir that turned into his first movie. Sadly, that's been long lost to time, but it kicked open the door to Micheaux's other films — and he didn't shy away from anything, especially when he was answering other filmmakers. The NAACP says his Within Our Gates was a response to Birth of a Nation, and it's the tale of a racist man who repents... when he realizes the woman he's about to assault is his illegitimate black daughter.

Oscar Micheaux died in 1951, while on a book tour. He wrote of his life's work, "It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights."

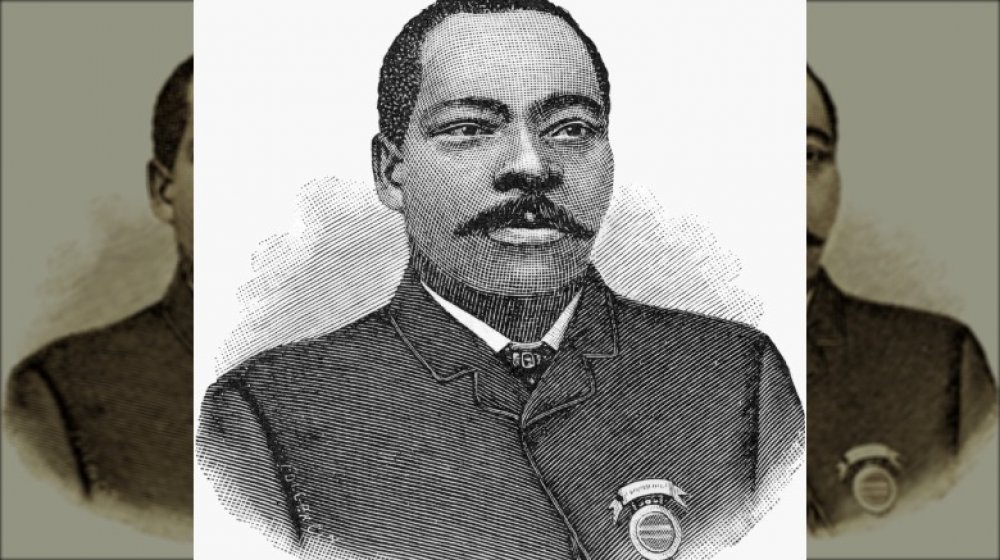

Granville T. Woods: The inventor that helped open the country

While many strive to come up with one brilliant idea that's going to change the world. Granville T. Woods had a ton of them: according to ThoughtCo., he held almost 60 patents, and had invented 15 devices that revolutionized the transportation industry.

Woods was born in 1856, leaving school at just 10-years-old to become an apprentice machinist and blacksmith. But 1872, he was working on the Danville and Southern railroad, and studying electronics — a brand-new field. But Woods' life was, to say the least, difficult.

Among the inventions he's credited with are the third rail (which supplies electrical power to rains from below instead of from overhead) — or, at least, improvements to it — and a communication system that allowed train conductors to send uninterrupted messages back and forth to stations, as well as an early version of an automatic air brake, that works even if the conductor's unable to pull it. But The New York Times says his fight for recognition was constant: at least a dozen of his patents went to court. He was constantly destitute, forced to take odd jobs to get enough cash to scrape by.

When he died in 1910 — of a cerebral hemorrhage, caused by smallpox — he was buried in a coffin along with three others. It wasn't until 1975 that the students of the Granville T. Woods School installed a headstone for him.

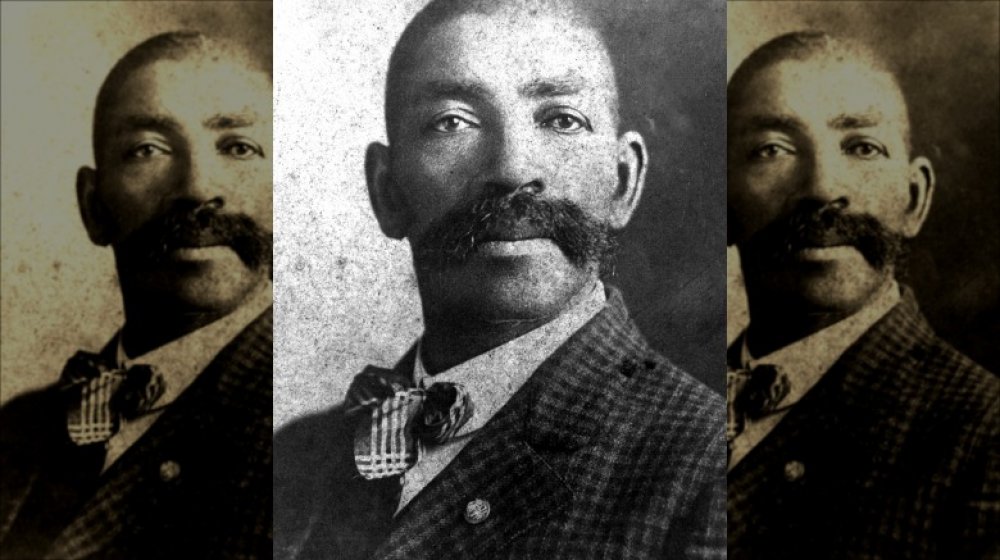

Bass Reeves: The real Lone Ranger

Sometimes, you hear about those incredible people who have life stories that just sound too insane to be true... and Bass Reeves is one of those people. He was born a slave in 1838, and when he was tasked with fighting for the Confederacy alongside his owner's son, he decided he was going to get out of Dodge... or, more accurately, head there.

He escaped into Indian Territory, fell in with the Seminole and Creek tribes, and after the end of slavery, he headed to Arkansas. According to History, it was 10 years before he'd go back to the territory where he'd found freedom and this time, he was working alongside US Marshal James Fagan. Reeves was one of around 200 deputy marshals that were recruited to try to return law to the lawless West, and no one can say that he didn't do his part: he's credited with arresting more than 3,000 people... including his own son, who was ultimately sentenced to life in jail for the murder of his wife.

Reeves's life story is the stuff of the silver screen, so it's not surprising that historians have posited he's the actual inspiration for the Lone Ranger. He even had such a strong sense of duty that he was 100 percent impossible to corrupt. According to The Washington Post, Reeves died in 1910 — when Jim Crow laws were ending the sort of freedom and authority he had.