The Crazy True Story Of The Weather Underground

A few hundred people took to the Chicago streets. Arms raised in protest, some donned football helmets while others carried steel pipes, baseball bats, and chains. Voices loud, they begged to be heard and demanded change. The smaller-than-expected crowd railed against the injustices of an oppressive system and unnecessary conflict, calling for change not through elections, but rather by "bringing the war home." Their "power [was] in the street." And their power came from militant action.

And so in October 1969, a small splinter of the peaceful Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) called the Weathermen stormed against the Vietnam War in what became known as the "Days of Rage." By the time it ended, hundreds of protesters had been arrested, personal property had been destroyed, cops and protesters were injured, and the Weathermen's attempts to spark reform came under harsh criticism, which ultimately forced the radical group to leave the SDS and head underground.

The Weathermen changed their name to the Weather Underground Organization, launched bombing campaigns against the establishment and became perhaps one of the most notorious, and violent, student-created activist groups of the 1970s. This is its crazy true story, one rooted in good intentions that grew into destruction, death, and federal investigation.

The well-intentioned beginnings of a movement are formed

The counterculture movement of the 1960s, birthed on college campuses across the country, is one of the defining moments in American history. The ideologies that sparked student-led revolution started in the post-World War II 1950s, a time of relative prosperity and peace in the country, at least according to the generation shaped by war and the post-Depression era. But the younger generation saw things differently. They saw the decade as a time of "complacency, stagnation, and authoritarianism" and one continuing the systemic oppression of African Americans.

Ideologies and concepts of political, social, and economic equality began to shape the minds of young people who sought to move away from the old guard in favor of a new left movement seeking and establishing a "participatory democracy." Participatory democracy is an idea established in a 1962 manifesto known as the Port Huron Statement, an ambitious and revolutionary call to action by the Students for a Democratic Society (not associated with the modern-day New Students for Democratic Society organization). The statement, as noted in The New York Times, is considered "the most ambitious, the most specific, and the most eloquent manifesto in the history of the American left."

The Weather Underground would ultimately spring from that kind of ambition, drawing on the ideologies of the manifesto and the original SDS.

The Weathermen predict a violent wind of change

The Weather Underground's early days started deep within the Students for a Democratic Society, the largest protest group of the 1960s dedicated to social, economic, and political change through predominately peaceful means. SDS was founded at the University of Michigan in opposition of white supremacy and in support of civil rights and economic reconstruction. While they scoffed at the establishment and corporate greed, the group was largely an "an amalgam of left-liberal, socialist, anarchist and increasingly Marxist currents and tendencies," according to Smithsonian Magazine. Soon after its establishment in 1965, its focus shifted to protesting the Vietnam War, and by 1969, it had grown to more than 100,000 members strong.

Yet, progress proved slow, and some members within SDS wanted a more no-holds-barred, in-your-face movement — that meant violence and bringing the war to the streets. One of those factions was the Weatherman (or the Weathermen), which took its name from a lyric in a Bob Dylan song: "You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows." And the wind was blowing extremely hard to the left when the Weathermen officially splintered off from the SDS in 1969. As one former member said: "When you feel you have right on your side, you can do some pretty horrific things."

The Weather Underground gets indoctrinated in communism

The Weathermen took a page from the communists' playbook, seeking to learn from the ideologies, doctrines, and social constructs established in Cuba. The country's communist government played a role in helping to radicalize the anti-establishment, anti-racism movement, meeting with key leaders of the Weathermen and supplying them with technical training and engaging in political brainwashing. "Beyond any doubt, Cuba has shaped [...] and served as the inspiration for the American radical movement [...] to bring down the American system that it so fiercely despises," according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

FBI documents reveal that an estimated 4,000 people tied to the 1960s movements visited Cuba for the purposes of learning how to best spark a full-scale revolution in America. Those people included academics, members of the New Left, and even violent activists bent on change. And a small number of them (about 30) were Weathermen, who met directly with Vietnamese revolutionaries in 1969, and whose "philosophy was an incendiary — some would say infantile — mix of Marx, Ché Guevara and Ho Chi Minh, lubricated by free love [...] LSD and daddy's cash," according to The Guardian.

"We didn't start it," one Cuban official told the FBI. "But we radicalized it, we gave it form. Every leader came and left with new ideas." And those ideas proved explosive in America.

The Weathermen issue the first salvo

The first shot across the bow came during the "Days of Rage" in October 1969, when the Weathermen took to the streets of Chicago, attacking property in the city's Gold Coast and facing off with police. The relatively small show of force for change backfired, as the four days of havoc garnered significant criticism and ridicule. The Black Panthers' Fred Hampton denounced the event as "anarchistic, opportunistic, individualistic, chauvinistic, Custeristic ... It's nothing but child's play — it's folly."

Stinging from the failed incursion, the Weathermen retreated and emerged in the spring of 1970 to issue a declaration of a state of war, per The New York Times. During a radio broadcast in California, the recorded voice of the Weathermen's Bernardine Dohrn threatened: "The lines are drawn. [...] Revolution is touching all of our lives. Freaks are revolutionaries and revolutionaries are freaks... within the next 14 days we will bomb a major U.S. institution."

And this time, the militants delivered. Bombs detonated at a number of governmental facilities, including the U.S. Capitol, a New York City courthouse, and a National Guard headquarters.

The Weather Underground springs an LSD guru from jail

As 1970 wore on, the stalwart Weathermen went underground, several of them as fugitives from the law following the fallout from the "Days of Rage" and a number of domestic bombings. And as they dug in and the cause went deeper, they officially became the Weather Underground Organization.

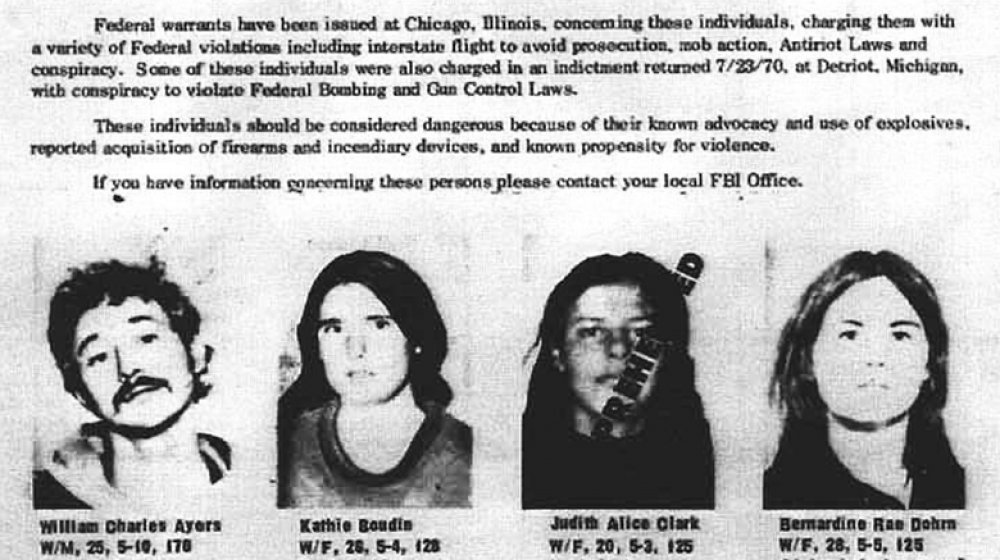

The WUO boasted a membership in the several hundred, hiding out scattered across the country in small communities of three to five people (think "cells") and all reporting to the Weather Bureau. The FBI believed the group to be nearly 4,000 strong, but in reality, it was much less than that. Still, the Bureau put a dozen of them on its Most Wanted List, and the WUO's members were media darlings because of their charisma, intelligence, and brash rhetoric — often at the expense of other leftist groups, according to Slate.

One stunt to call attention to injustice was to stage the prison break of counterculture psychedelic guru Timothy Leary. A new age cult called the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, whose core principles included the use of LSD, put up nearly $20,000 to help the WUO spring Leary from a California jail, where he was being held on minor pot possession charges. "It was a real poke in the eye to California and the drug laws," said one Weather Underground member. "It was a big [expletive] you." To who? The establishment, the "Amerikan justice" system.

An explosion rocks Greenwich Village and kills three Weathermen

The "Amerikan justice" system set its sights on the radical cult (as some called it) and its most wanted members, including Bernardine Dohrn, Bill Ayers, Kathy Boudin, and Cathy Wilkerson, who had seemingly vanished after March 6, 1970. On that day, a violent explosion rocked a historic Greenwich Village townhouse, once owned by a founder of Merrill Lynch and considered to be the headquarters of the Weathermen. The townhouse, owned by Wilkerson's father, served as a pipe bomb-making factory for the group, with the first one intended for use in blowing up a Fort Dix, New Jersey, officers' club.

That first attempt did not reach its intended target. Instead, the pipe bomb exploded in the basement and detonated cases of dynamite. The blast leveled the townhouse and killed three of the Weathermen — Terry Robbins, Diane Oughton, and Ted Gold — the only deaths connected to the Weather Underground bombings. "The political point of the town house was that we had to take on the U.S. military, like we were a third world country," Wilkerson told The New York Times. "The accident at the town house showed the absurdity of our approach."

Wilkerson and Boudin, the sole survivors of the deadly explosion, crawled from the wreckage, fled the scene, and went into hiding. They would not resurface for more than a decade.

The Weather Underground launches a reign of 'terror'

Over the course of the next decade, the Weather Underground took responsibility for 25 domestic bombings, all in the name of sparking a social justice revolution. The group would almost always target empty buildings at night or give advanced warning of the attacks on the mostly government buildings, according to The Guardian. The list of their bombing campaign includes some impressive locations like the Pentagon, the U.S. Capitol, a New York City police precinct, and the offices of the California Attorney General.

Not one person was killed in these bombings, yet the media — and the feds — were quick to label the Weather Underground terrorists. "We don't think, individually or as a group, that we were terrorists," Bernardine Dohrn told an audience at the University of Michigan (where it all started) in 2009. "We never did, and we don't think terrorism is a good idea. But the Weather Underground broke through a lot of barriers — there were 2,000 people dying a week in Vietnam, and we had 500,000 soldiers occupying a tiny country, involved in acts that would be considered war crimes by today's framework. I don't defend it, but I do insist on explaining it."

The Weather Underground's famous leaders resurface

Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn are two of the more prominent, and infamous, members of the Weather Underground. Dohrn was the disembodied voice that declared war on America during a California radio broadcast in 1970, as well as the primary issuer of communiqués that gave warnings about the group's radical movement. Ayers — seen in famous photographs from the "Days of Rage" donning a football helmet and leading the charge — was a founding member of the militant organization and has little remorse for its violent actions. "I don't regret setting bombs," Ayers told The New York Times in 2001. "I feel we didn't do enough." The couple, married with three children, went underground for more than a decade, and their time spent as fugitives from justice became the basis for the 1988 movie Running on Empty, starring Judd Hirsch and River Phoenix.

"I believe in the necessity of underground work, so I am returning to the open life with a sense of loss as well as hope," Dohrn said in a Chicago courtroom when she came out of hiding with Ayers in 1980 and surrendered to police on charges associated with the "Days of Rage" riots. "I'm eager to discuss the lessons of the 60s and 70s, including my errors and wrong directions as well as our strengths and successes." By this time, any federal charges against Dohrn and Ayers, and others in the WUO, had been dropped because of missteps in the FBI investigation.

The war ends, but the cause continues for the Weather Underground

The U.S. government agreed to a cease-fire accord in Vietnam in 1973, a tipping point in the anti-war protests leading up to it, at times with more than 50,000 people taking their power to the streets. By March of that year, American troops had withdrawn, but the movements and protests it sparked continued. In the end, the cease-fire and troop withdrawal did little to help the Vietnamese people but rather served as a "face-saving gesture" by the US, according to History: "Even before the last American troops departed on March 29, the communists violated the cease-fire, and by early 1974 full-scale war had resumed."

And the Weather Underground's explosive protests raged on, too, targeting high-value locations like the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare in San Francisco, Gulf Oil's Pittsburgh headquarters, and the State Department in Washington, DC. The militants also continued communiqués advancing the cause of black liberation, social justice, and political upheaval, including the Prairie Fire, issued in 1974. The document was the group's "political ideology — a strategy for anti-imperialism and revolution inside the imperial US" that called on others to join the cause and advance it.

Ultimately, by 1976, the momentum slowed, and the Weather Underground started to disband, a process that would take the next five years ... and see the re-emergence of a number of its fugitive members into mainstream society.

The Weathermen surrender to their fates

Re-entry into society started in earnest for the remaining Weather Underground members, who began to resurface in 1977. Cathy Wilkerson, who vanished after running from the razed and burning Greenwich Village townhouse in 1970, surrendered to police, pleaded not guilty to criminally negligent homicide, and ultimately received three years in prison for the townhouse incident. While many Weathermen resurfaced and surrendered on various criminal charges, Wilkerson was the only one to face homicide charges.

Another ghost from the deadly townhouse explosion resurfaced in 1981, perhaps in an even more shocking way than when she disappeared. As detailed by The New York Times, on October 21, 1981, in a brazen daylight assault, a group of heavily armed suspects in ski masks robbed a Brinks armored truck at a mall in Nanuet, New York, taking more than $1.5 million and killing one of the guards, Peter Paige. A subsequent shootout with the robbers killed two Nyack police officers. Police arrested several people — one of whom was Kathy Boudin, who escaped the townhouse with Wilkerson a decade earlier.

Boudin served 22 years in prison for her role in the heist. Her accomplices, and fellow Weathermen, Judith Clark and Boudin's partner David Gilbert, were also sentenced to prison for their crimes. Clark was released in 2019, and Gilbert remains behind bars. With the death of the police officers and the guard, and the incarceration of the last of the radicals, the movement and the ideology of the Weathermen died.

The Weather Underground's lessons live on

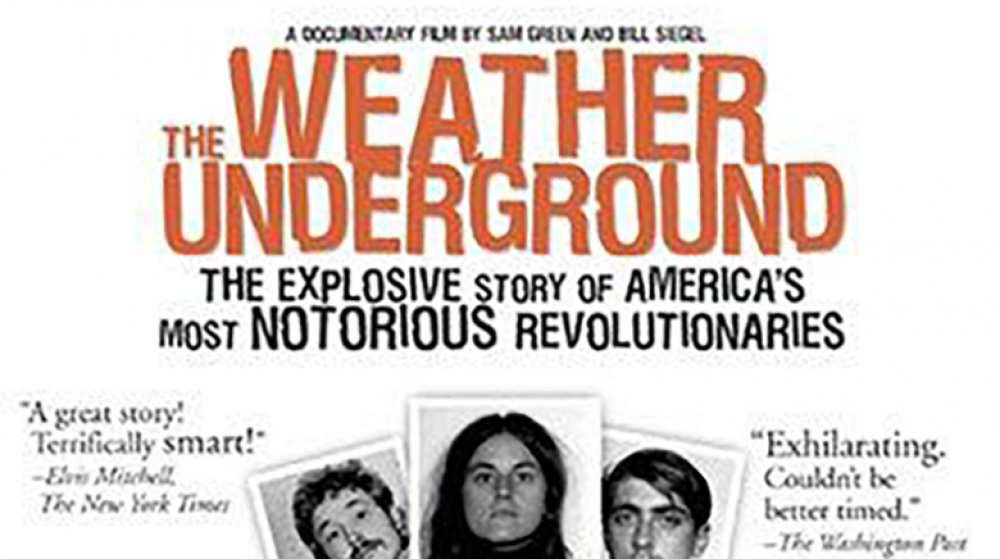

Though the Weathermen ceased to exist by 1981, the name lives on ... as a weather forecasting database created in the 1990s at the University of Michigan, where it all started. The group's story became an Oscar-nominated documentary, and former members have gone on to contribute through careers in academia, law, and activism. Even 40 years later, some of the same battles for justice rage on.

Bernardine Dohrn became an associate professor at Northwestern University's Children and Justice Center. Today, per the Chicago Tribune, she is retired yet still active, with her husband Bill Ayers, in a number of causes. Ayers published a memoir of his time as a central figure in the Weather Underground movement and as a fugitive from justice. He is also active in school reform and is a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago.

Kathy Boudin, who was released from prison in September 2003, went into clinical social work and was the co-director/founder of the Center for Justice at Columbia University. She focused her work on the causes and effects of incarceration, drawing on her own experiences with the injustices of the penal system. In addition, Boudin worked to promote HIV/AIDS prevention and education. She later died from cancer at age 78 in May 2022, as noted by The New York Times.

Cathy Wilkerson also penned a memoir of her experiences in the Weather Underground. She served her sentence for the townhouse incident and has spent the past decades in education as a math teacher. In her memoir, she writes: "We threw ourselves into the possibility of remaking ourselves as more effective tools for humanity's benefit to the point of sacrificing our own humanity."