The History Of Juneteenth Explained

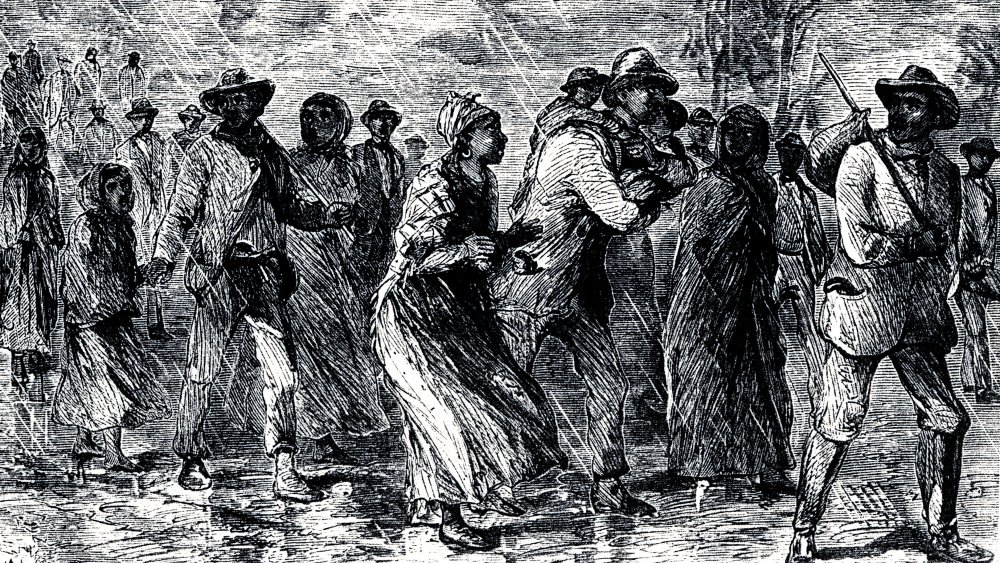

In the United States, June 19th marks an auspicious day in history. It was the day in 1865 when Major General Gordon Granger of the Union Army arrived in Galveston, Texas and read the following words.

"The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor."

The announcement, known as General Orders, Number 3, wasn't perfect or ideally timed — it went on to advise freedmen to stick around and see if they could work out a paid gig with their former "owners," and it came some two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation. In a particularly thoughtful piece published by PBS, Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. points out that the 1,800 Yankee soldiers under Granger's command couldn't enforce the announcement across all of the Lone Star State, with many theoretically freed slaves remaining in bondage out of fear, while others were killed by angry whites while trying to escape.

Juneteenth and the fight for a more perfect union

Nevertheless, Granger's announcement on June 19th, 1865 marked a significant milestone. Texas was the final Southern state to receive official notice of emancipation orders. If nothing else, it was an important step, and on December 18th of that year, the 13th Amendment was formally adopted, pronouncing that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

In 1979, Texas became the first state to declare Juneteenth a "holiday of significance." Celebrations of the date continued to snowball, especially after the turn of the millennium, and today, Juneteenth is officially recognized in every state, save North Dakota, South Dakota, and Hawaii. Festivities vary from place to place, but tend to focus on historical education, cultural appreciation, political causes, and the abolition of modern slavery, which is estimated by the International Labor Organization to affect roughly 25 million people annually.