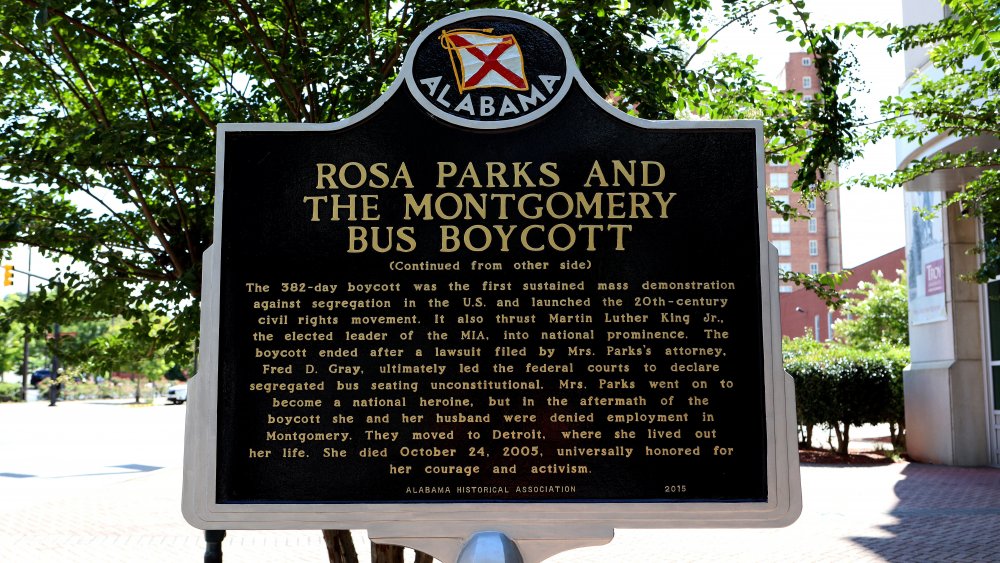

The Messed Up Truth About The Montgomery Bus Boycott

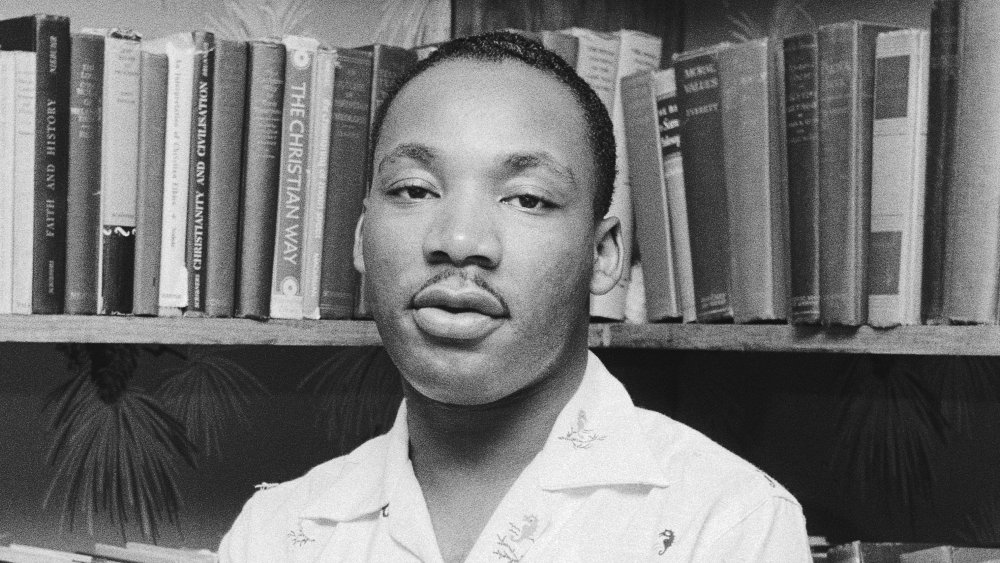

The Montgomery bus boycott is often hailed as the opening act of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. It brought national and international attention to the racism institutionalized in Southern life for the first time in decades, created a playbook for peaceful protest, and introduced the world to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The story you learned in school probably went something like this: In 1954's landmark case Brown v. Board of Education, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) convinced the Supreme Court to overrule the "separate but equal" doctrine that had formed the legal basis for racial segregation since 1896. In 1955, black Montgomery resident Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white man on a bus and was arrested. The black residents of Montgomery, led by King, protested by boycotting the city's buses. Eventually, the city relented, and the buses were desegregated.

That isn't exactly wrong. Parks did get arrested, King did emerge as a leader, and the buses were desegregated. But this version of events leaves out the heroic efforts of multiple people who risked arrest and sometimes their lives to work tirelessly towards desegregation. It also skips over the efforts of white city officials and bus company representatives to stop the boycott from achieving its goal. The messed-up truth about the Montgomery bus boycott is that it took even more courage, tenacity, and teamwork than you realize to chip away at the racist policies dominating the South.

The Montgomery bus boycott was not spontaneous

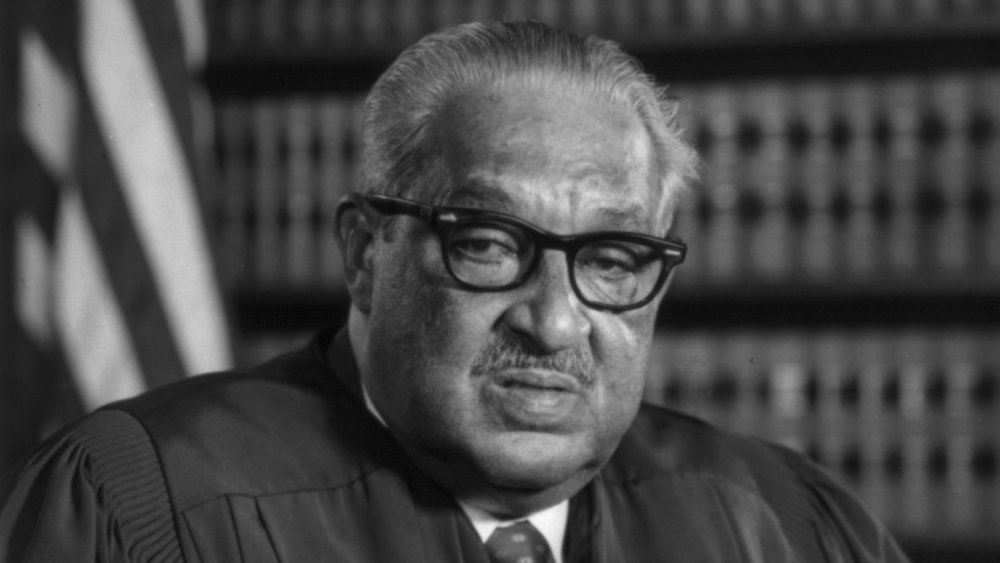

Black civil rights leaders were laying the groundwork that would support the Montgomery bus boycott for years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat. The NAACP had started looking for ways to tackle segregation on intrastate public transport in 1951, three years before Brown saw "separate but equal" ruled unconstitutional. The organization's chief legal counsel (and civil rights legend) Thurgood Marshall told local chapters to look out for lawsuits regarding discrimination against black people on public transport which could be used to challenge segregation. Just a few months after Brown, in June 1954, the NAACP found one in Columbia, South Carolina. A driver ordered Sarah Mae Flemming to move from the white section of a bus and elbowed her in the stomach when she tried to leave through the front door at the next stop. The case was moving through the courts by the time Rosa Parks was arrested.

Meanwhile, in Montgomery, the Women's Political Council (WPC) — an organization designed to get black women involved in politics and activism — set their sights on segregation on the city's buses. By 1955, they had three chapters in Montgomery, with around 300 members. Stanford's Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute says they'd challenged city commissioners about racist practices on buses multiple times, including the rule that forced black people to pay at the front and re-enter in the back. A letter from WPC president Jo Ann Robinson dated May 21, 1954 threatened a boycott over the continued segregation and abuse.

Rosa Parks' moment of activism was not a one-off

Some portrayals of Rosa Parks depict her refusal to give up her seat for a white man as a spontaneous moment of rebellion. For example, there's a widely circulated myth that the reason Parks didn't want to stand was that her feet hurt after a long day at work. Mark that down as one of those things about the civil rights movement your history teacher got wrong. Parks herself wrote in her autobiography, "I was not tired physically... No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in."

This was not Parks' first moment of civil rights activism: she was a well-respected secretary for the local chapter of the NAACP, which she'd joined in 1943. Although she knew they were looking for test cases that could challenge segregation on intrastate public transport, Parks wrote that she hadn't planned to get arrested that day. But when she did, she became the perfect defendant.

Other black people had been arrested in Montgomery for resisting segregation on buses: WPC President Jo Ann Robinson cited more than 14 cases. For example, a woman named Viola White was arrested in 1944, but 11 years later her case was still being held up in the courts. Teenager Claudette Colvin was arrested on March 2, 1955, but was deemed an unsuitable defendant when she got pregnant. Parks' squeaky clean middle class lifestyle made her the one activists had been waiting for.

You've probably never heard of the woman who organized the first boycott

If you've been reading this article carefully, you know that Jo Ann Robinson was the president of the Women's Political Council (WPC) in 1955. But you may not know that it was Robinson and the WPC who helped get the Montgomery bus boycott off the ground.

When Robinson heard Rosa Parks had been arrested for protesting segregation, she launched the WPC's plan for a citywide bus boycott into action. She typed a leaflet on her home typewriter, then went to Alabama State College — where she worked — and spent the rest of the night making 35,000 copies (which she and colleague John Cannon cut in half by hand.) The next morning, Robinson distributed the leaflets to the members of the WPC through stealthy drop-offs at schools, since many were teachers. That afternoon, she met with ministers to plan the boycott.

Robinson's initial plan was for a one-day boycott on Monday, December 5. If that proved successful, she was ready to defer to the ministers, to see if they wanted to organize a longer boycott. With the support of the community, they decided to continue and, according to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, also formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to help coordinate the ongoing effort. Robinson served on the MIA's executive board, writing the weekly newsletter, and drove in the carpool.

The Montgomery bus boycott lasted over a year

The first day of the Montgomery boycott was originally going to be the only day: Monday, December 5, 1955. Long-standing Montgomery activists Jo Ann Robinson and E.D. Nixon got the word out. Robinson distributed her leaflets, and Nixon had white journalist Joe Azbell run a story about the boycott in the Sunday edition of the Montgomery Advertiser. Nixon also paid Rosa Parks' bail, and gathered local ministers together to help publicize the boycott in their services.

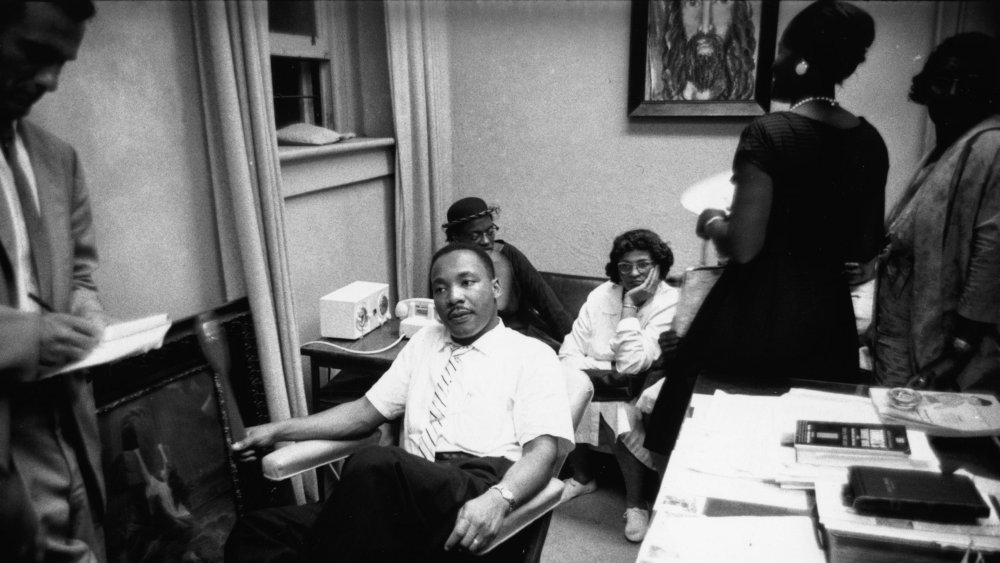

It was already winter at this point, and many of the city's black residents worked several miles away from their homes. But that day, about 90 percent of black riders (and even some whites, according to Robinson) stayed off the buses. On the evening of December 5, the just-formed MIA held a meeting for black residents to decide how to proceed. Thousands of people attended, filling the large church and standing outside, listening to the speeches through loudspeakers. Those speeches included Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s first major address to a big crowd.

There were numerous obstacles facing the activists and the organizers, including not just impending poor weather but brazen white hostility and violence. But a unanimous vote held at the meeting turned the boycott from a one-off to indefinite. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute says what was supposed to be just one day ultimately lasted 381 days, thanks to the MIA's commitment to overcoming logistical hurdles and the residents' determination and courage.

Martin Luther King, Jr. did not initiate the Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was the first time Americans heard of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as the leader of a civil rights movement — and he was only 26. King was elected president of the newly formed Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), which ran the boycott, but he didn't exactly volunteer for the role.

According to Jo Ann Robinson, King at first declined because he recognized that he was young and inexperienced compared to other local leaders and ministers. However, King's relative greenness was actually seen as a benefit: he hadn't been in Montgomery long enough to make enemies, which meant he could unite the various factions in the city's black community.

Robinson and Montgomery NAACP president E.D. Nixon both insisted there was something special about King from the start. Nixon was the one who called all the ministers to meet at King's church the day after Rosa Parks' arrest, and claimed that he cajoled King into taking a leadership role. He told interviewers in 1979 that when he'd heard King talk in August 1955, he'd said, "one of these days I'm gonna hang him to the stars." Robinson also praised King, saying that despite his initial reluctance, "he was dynamite... Martin Luther King was one of the few men who could have done what we were able to do in Montgomery."

The organizers didn't initially try to desegregate buses

The original aims of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) were surprisingly conservative and did not include completely eliminating segregation on the city's buses.

On the night of the first day of boycotting, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute says the just-formed MIA presented three demands to the thousands of black Montgomery residents who had gathered inside and outside a large church, for a vote. First, the MIA wanted first-come first-serve segregated seating. Different parts of each bus would be set aside for people of each race, but black people would not have to give up their seats for white people or stand next to an empty seat. Second, bus drivers had to treat all customers with courtesy: black passengers were often subject to abuse from drivers. Third, the bus company should hire black bus drivers for routes that went through areas of the city that were predominantly black.

After a unanimous vote, King and the other MIA leaders took these demands to city officials and lawyers from the bus company on the third day of the boycott, but the lawyers refused to compromise. Eventually, it became clear that this halfway approach was not going to work — partly because the NAACP was no longer helping in cases that accepted some level of segregation. On February 1, 1956, Fred Gray and Charles D. Langford (lawyers for the Montgomery activists) filed a federal district court petition challenging the constitutionality of Alabama's laws requiring segregation on buses.

Rosa Parks wasn't named in the Supreme Court case that overruled segregation on buses

The Montgomery activists' initial plan was to use Rosa Parks' case to test — and break — segregation laws in the Supreme Court. But this plan hit a few problems. First, getting a Supreme Court decision could take years, and the boycott organizers were already struggling to help people get to work without buses. Second, lawyers Fred Gray and Charles D. Langford worried that Alabama courts might refuse to rule on Parks' case on a technicality, or might rule using Alabama state law. Both would mean neatly sidestepping the question of segregation at a federal level.

Instead, with help from NAACP lawyers, on February 1, 1956, Gray and Langford filed a lawsuit against various city officials (Browder v. Gayle) on behalf of four women who had resisted segregation laws on Montgomery buses. Those unsung heroines were Aurelia S. Browder, Susie McDonald, Claudette Colvin. and Mary Louise Smith. The lawsuit challenged the constitutionality of the Alabama and Montgomery statutes that required buses be segregated according to race.

Challenges to state statutes get a fast-pass through the federal legal system, and this case was given priority, according to one of the judges, to prevent social unrest. On June 5, 1956, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute says a US District Court panel ruled two to one in the women's favor — but the Montgomery activists had to wait until the Supreme Court heard the appeal before anything changed on the ground.

City officials pulled dirty tricks to try to end the boycott

The white officials running Montgomery did everything they could to undermine and extinguish the bus boycott. Police Commissioner Clyde Sellers tried to paint the activists as bullies holding the black community hostage. On the first day of the boycott, he sent police to follow the buses, claiming there were "goon squads" ready to attack black riders who broke the boycott. Jo Ann Robinson said this actually further discouraged would-be riders, who were more afraid of police violence than they were of repercussions from their own community.

The city also threw up bureaucratic obstacles. When black taxi drivers started charging black riders less than the normal fare to get to work, Sellers had his cops enforce a minimum fare, revoking the licenses of those in violation. The MIA responded by forming a carpool, but lawyers for the city dug up an anti-labor law that was used to indict 89 defendants, starting with King, who was found guilty, fined, and given bond pending appeal.

The MIA wasn't the city's only target in its petty crusade to maintain segregation. In April 1956, the Montgomery bus company tried to desegregate its buses following a Supreme Court decision in the case involving Sarah Mae Flemming. The city sued, arguing that Alabama law still stood, and Judge Walter B. Jones ruled in their favor. Add him to the list of judges too ridiculous to be real.

The Montgomery bus boycott was won — and nearly lost — in the courtroom

The courageous daily actions of the bus boycotters forced white people in Montgomery and around the US and the world to confront racism and segregation. But a group of activists was also fighting a battle in the courtrooms — and had they lost, the whole protest might have collapsed.

In the early days of the boycott, the MIA organized a volunteer carpool of 200 drivers to get people to work. They couldn't charge riders because that would violate city ordinances, so the increasingly expensive carpool — $3,000 to $5,000 a week — was funded through donations and church collections. It became even harder to maintain when white-owned insurance companies suddenly canceled policies on cars the MIA had purchased and registered to various churches.

The carpool became the city's main target in its quest to crush the boycott. Police harassed, fined and arrested riders and drivers on false charges. Then the city sued the MIA, using an anti-labor law that barely applied. Martin Luther King, Jr., the first defendant, was found guilty, and the other cases were postponed pending his appeal. On November 13, 1956, King was in court for that appeal, a decision which would have seriously undermined the MIA's ability to help people continue to boycott buses. During the hearing, King learned that the Supreme Court had struck down segregation on buses in Browder v. Gayle: the boycotters and the MIA had won.

Black activists faced backlash from the white community

The backlash against activists was persistent and often violent. During the boycott, the activists were regularly harassed by police offering trivial excuses, especially by cops who had worked as bus drivers before being made redundant following the bus company's loss of income. The movement's prominent figures were threatened and attacked. Lawyer Fred Gray was pulled over regularly for trumped up traffic violations, received threatening phone calls, and was even arrested for a tenuous legal technicality. Police broke the window of Jo Ann Robinson's house, and poured acid over her car. On January 26, 1956, King was arrested for the first time, for allegedly going 5mph over the speed limit. He was released and fined, but four days later his home was bombed. King would spend the rest of his life as a target: and there are things we still don't know about MLK's death.

The boycott officially ended on December 20, 1956, the day the Supreme Court ordered Montgomery to actually carry out desegregation on buses. A few days later, someone fired a gun into King's house. On December 28, snipers attacked a desegregated bus, shooting a pregnant woman in both legs (fortunately she survived.) The city canceled all bus services after 5pm — a problem for people trying to get back from work. In January 1957, several black churches and the homes of Robert Graetz and Ralph Abernathy were bombed. Seven white people were arrested, but none were ultimately convicted.