Why It Took So Long For Lynching To Become A Federal Crime

On March 29, United States President Joe Biden signed H.R. 55 — better known as the Emmett Till Antilynching Act — bringing to an end a century-long battle over classifying lynching as a federal crime. "Lynching was pure terror to enforce the lie that not everyone, not everyone belongs in America, not everyone is created equal," President Biden said in the White House Rose Garden alongside civil rights leaders (via The New York Times). "Terror, to systematically undermine hard, hard fought civil rights. Terror, not just in the dark of the night, but in broad daylight. Innocent men, women and children hung by nooses from trees," he said. "Bodies burned and drowned and castrated. Their crimes? Trying to vote, trying to go to school, to try and own a business or preach the gospel."

Vice President Kamala Harris echoed the president's sentiments, and was one of the bill's sponsors while she was still serving as a senator. "It failed again and again and again and again," she said of Congress's efforts to get such a bill passed into law.

What is lynching?

According to Britannica, lynching is a form of extrajudicial killing in which a presumed offender is executed, typically by hanging, without any form of a trial. The act often includes the torturing and mutilation of the victim. Throughout history, lynchings have been typically carried out by mobs who claim to be acting in the name of justice. While lynching has unfortunately been woven into the fabric of American History — especially in the decades after the Civil War — similar acts intended to seek justice outside the traditional legal system have been seen in different places and time periods, including medieval Germany and Spain.

Where the English term lynching even came from is up for debate, though it's typically attributed to someone whose last name was Lynch. According to Britannica, it stemmed from Charles Lynch, who ran a court in colonial Virginia during the American Revolution that targeted loyalists. Others have claimed it was named after William Lynch, a slave owner in Virginia in the early 19th century (via Baltimore Sun). Others have even argued that the term dates back even further and across the Atlantic Ocean, attributing it to James Lynch FitzStephen, a 15th century mayor of Galway, Ireland, who was executed by a mob after being suspected of murdering a house guest (via Irish Central).

Lynching in the United States

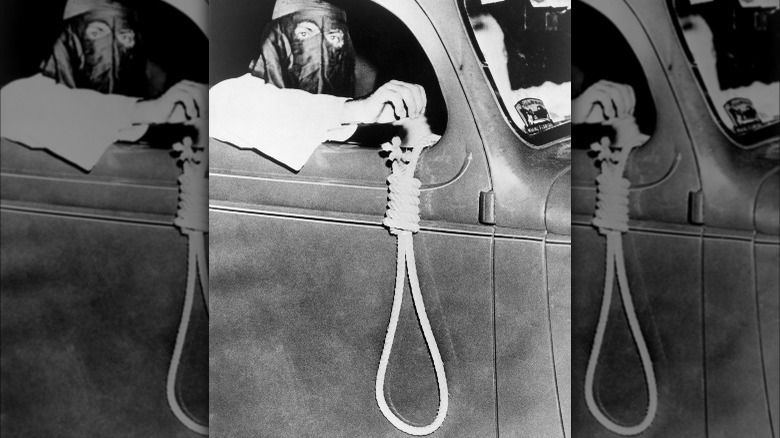

Regardless of where it come from, for many people the term lynching immediately brings to mind racially motivated mob killings that occured throughout the 19th century and into the middle part of the 20th century. According to The New York Times, just between 1870 and 1950, as many as 4,400 lynchings were carried out against Blacks in the United States. This was the greatest number of racially motivated lynchings carried out anywhere in the world during that time (via Equal Justice Initiative). While these acts were often carried out under the guise of justice, PBS points out that lynching was also used as a form of terrorism, designed to promote racial subordination and white supremacy in all facets of life, including politics.

Lynching existed before the Civil War, but it became far more prevalent in the years after the war, known as Reconstruction. During this time, primarily Black towns were being established, and this was coupled with the ability for Blacks to vote. This made some whites, mostly landowners or those who were poor, feel threatened. They were also concerned about the prospect of sexual relations between the two races and began perpetuating blatantly false narratives that Black men were sexual predators. Race-related violence decreased during World War II, but unfortunately that trend didn't continue, as it picked up again following the Supreme Court's 1954 ruling on Brown v. Board of Education.

The murder of Emmett Till

The false narrative that Black men were sexual predators was the crux of the Emmett Till lynching. Till, 14 years old, was tortured and murdered in 1955. He became the namesake for the bill that was signed into law in 2022 by President Biden. According to History, Till was from Chicago, but in late-August 1955, he was visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi. On August 28, the wife of a local store claimed that Till had flirted with her and even tried to grab her, claims that would later be proven to be completely untrue. Upon hearing his wife's story of Till's alleged behavior, the shop owner and his half-brother went to the home of Till's great-uncle Moses Wright, where Emmett was staying.

They forced Till into their car, and while not much is known about exactly what happened, it's believed that the 14-year-old was repeatedly beaten as well as mutilated. Three days later his severely beaten body was found near Tallahatchie River. Due to the condition of Till's body, authorities wanted to bury him in Mississippi, but his mother, Mamie Bradley, had her son's body returned to Chicago. Bradley requested that her son's funeral be open-casket so that the world could see what had been done to him. The two men accused of Till's murder went on trial just two weeks later, but with very few witnesses to provide their testimony, the all-white jury found the men not guilty.

Previous attempts at making lynching a federal crime

Quite a few attempts at making lynching a federal hate crime have been made. In 1900, Rep. George Henry White of North Carolina — who was the only Black member of Congress at the time — presented a piece of legislation that was intended to classify lynching as a crime (via Visit the Capitol). Despite also presenting a petition with over 2,000 signatures in support of his bill, H.R. 6963 failed to clear the Judiciary Committee and never became law.

According to The New York Times, in the years that followed, attempts were made once again to have lynching classified as a federal crime, but lawmakers failed to get it passed a staggering 200 times, something the United States Senate formally apologized for in 2005. Still, it took another 17 years for a piece of legislation to bring what civil rights activists like Rep. George Henry White had fought for over the course of decades.

An antilynching law comes to fruition

The bill that President Biden signed into law on March 29 was introduced in Congress on January 4, 2021. H.R. 55, or the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, as it's known, came on the heels of a failed attempt at passing a similar bill in 2020 (posted at Congress.gov), which cleared the House but failed to get past the Senate. It was introduced by Rep. Bobby Rush, whose district comprises part of Till's hometown of Chicago, Illinois.

One of those on hand to see the bill signed into law was Michelle Duster, the great daughter of Ida B. Wells, a journalist at the turn of the 20th century who fought for this kind of law and who documented lynching cases. She was also one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). "She carefully chronicled names, date, locations and excuses used to justify lynchings. She wrote articles and pamphlets and gave speeches about the atrocities," Duster said of her great-grandmother's efforts (reported by The New York Times). "Despite losing everything, she continued to speak out across this country and Britain about the violence and terror of lynching."