The Crazy True Story Of The Protesters Who Took Over Alcatraz

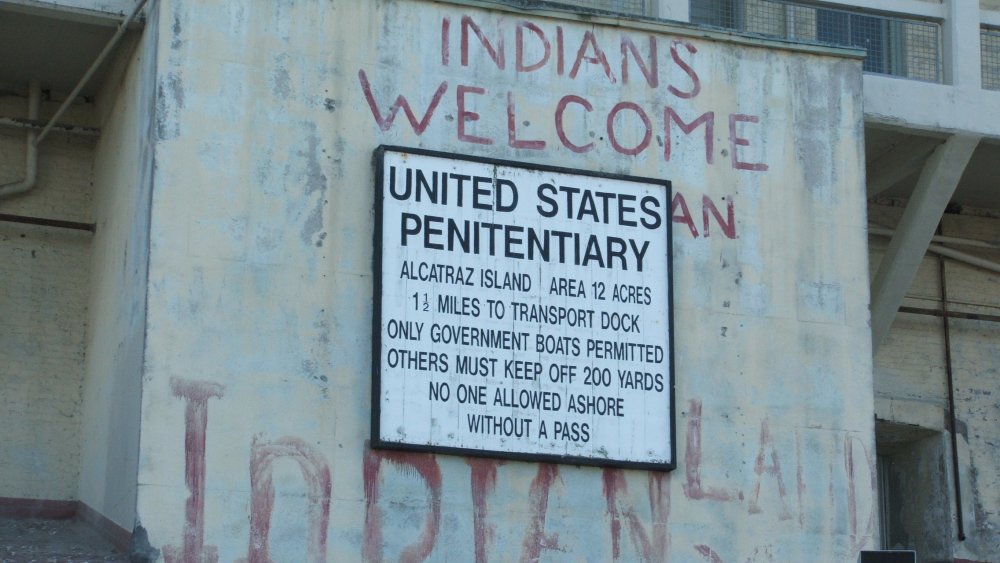

Known primarily for its infamous reputation as a prison, Alcatraz Island has a sordid history. Taken from its Native residents in the late 1700s, the island was primarily used as a penitentiary by the United States government, at one point housing a number of high-profile criminals. But from 1969 to 1971, this history was punctuated by Native reclamations of the island, the effects of which are still felt. After the prison was closed, protesters attempted to reclaim Alcatraz, hoping to turn it into a Native cultural center.

While the occupation was ultimately unsuccessful in reclaiming Alcatraz Island for the First Nations, it was hugely successful in bringing the urgency of Native rights to the forefront for the American Non-Native public. Lasting a little under two years, the attempted reclamation of Alcatraz led to significant changes in Native self-determination in the United States as well as worldwide, an achievement in nonviolent opposition. This is the crazy true story of the protesters who took over Alcatraz.

The history of Alcatraz Island

For hundreds of years, Alcatraz Island was used as a fishing base by the Ohlone people, who lived along the Northern Californian coast. According to Legends of America, while the island was used for food gathering, it was also associated with evil spirits and at times was used as a place of exile. Westerners stumbled across the island in 1775. It was then that it received its notorious name from Spanish explorer Lieutenant Juan Manuel de Ayala. Noticing the many seabirds that perched on the island, Ayala referred to the island as "Ysla de Alcatrazes," which translates roughly to "island of the pelicans."

After the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors, the Ohlone people were decimated: They were killed by disease, murdered by Spanish soldiers for refusing to convert, and, for those who did convert, subjected to unclean facilities at missions. Many Ohlone who resisted conversion were eventually enslaved and forced into converting. Others fled and hid on Alcatraz, thinking the Europeans would not think to look for them in a place that they thought the Ohlone feared.

The Spanish mission system ended in 1834. Shortly after, in 1846, the land was purchased by the United States. For a time, the island was home to the first working lighthouse on the West Coast, but by 1861, it had been converted into a military prison. It was used as a penitentiary for roughly a century until its closing in 1963.

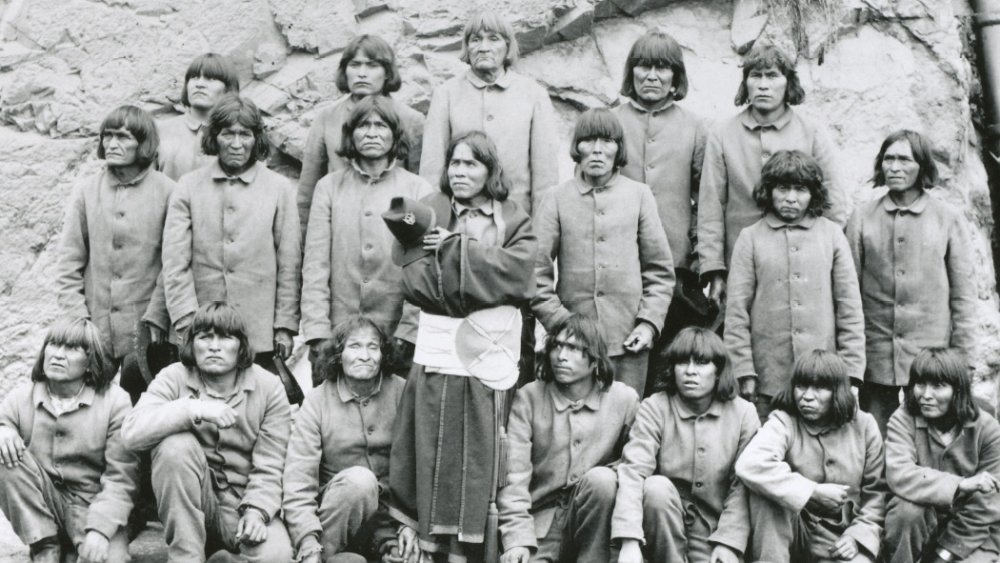

Hopi prisoners on Alcatraz Island

The next time indigenous people were on the island, it was as prisoners. In 1887, the United States passed the Dawes Act, which sought to dissolve tribal land holdings and convert them into private property, in principle to be dispensed back to indigenous people by the government. There was a simultaneous push by the US government at this time to "Americanize" Natives, especially through the indoctrination of children. Boarding schools were set up, with inadequate conditions and unclean facilities. Government agents would regularly try to coerce Native parents into sending their children away. Many families resisted the coercion, leading the US government to abduct them by force.

In December 1890, soldiers invaded Orayvi, a Hopi village in what is now Navajo County, Arizona, and took 104 children to the Keams Canyon School. When the government sent policemen to round up more children in 1894, they were met with resistance. They therefore decided to send soldiers to arrest the village leaders who were refusing to yield their children to assimilation.

In November 1984, those 19 Hopi men were arrested and imprisoned in Alcatraz for almost a year because they refused to give up their children. In 1895, the San Francisco Chronicle reported twice on the Hopi men imprisoned on Alcatraz and, in articles riddled with racist rhetoric, proclaimed that "prisoners they shall stay until they have learned to appreciate the advantage of education."

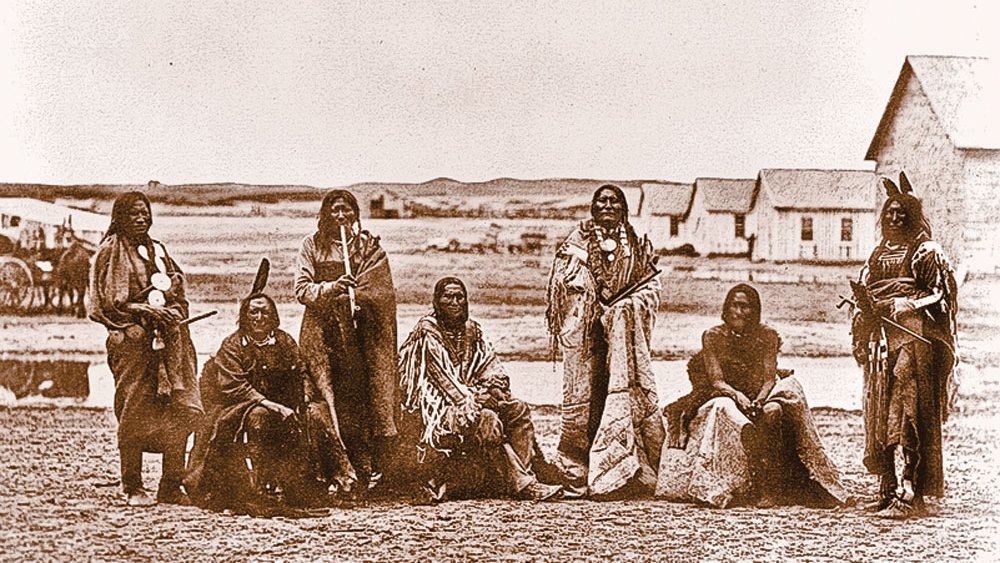

The first reclamation of Alcatraz Island

The first attempted reclamation of the island occurred in 1964, one year after Alcatraz's use as a penitentiary was discontinued. Having read in the newspaper of the government's indecision about what to do with Alcatraz, Belva Cottier, a Sioux woman living in the Bay Area, recalled the Sioux Treaty of 1868, which stated that Natives were entitled to reclaim surplus land from the United States. With her husband and four other Sioux men, Cottier hatched a plan to reclaim Alcatraz.

They weren't secretive about their intentions. In an interview, Cottier remembers how they called the news media as well as Washington to let them know of their intentions to claim Alcatraz. Few believed them, and even fewer showed up. Nevertheless, evading police guards, they made their way onto the island and planted their claim sticks. As they read their proclamation claiming the land for all tribes via the 1868 treaty, the officials remaining on the island called the Federal Marshal. After only a few hours, they were taken back to shore, but Cottier recalls that "we felt that we had completed our mission by testing the 1868 treaty."

1969 reclamation of Alcatraz Island

On November 9, 1969, a group of Native people once again attempted to reclaim Alcatraz, organized in part by Adam Fortunate Eagle, Richard Oakes, and LaNada War Jack (at the time, LaNada Means), though the movement was a deeply communal effort. While almost 75 people had shown up to reclaim the island, when the boats they had arranged didn't show up, Fortunate Eagle had to quickly find another mode of transportation.

As a result, only a small group of them made it onto the island that day, but upon landing, they claimed Alcatraz by "rights of discovery" in the name of Indians of All Tribes. Reclaiming the land for all Native people, they even offered to buy Alcatraz from the United States government for $24 "in glass beads and red cloth, a precedent set by the white man's purchase of a similar island about 300 years ago," that also generously accounted for the increase in land values. Once again, the Coast Guard removed them after a couple of hours, but the people were galvanized.

On November 20, the group once more secured passage to Alcatraz, and this time, they were able to sustain their presence. This time, over 70 people were able to land on the Rock, leading the Los Angeles Times to report, with no sense of irony, that Natives were "invading" the island.

The beginning reorganization and negotiations of Alcatraz

The number of occupiers quickly rose to almost 1,000 by the following week, which was Thanksgiving. When a thanksgiving meal was brought in by boat for the occupiers, the occupiers relayed another humorous jab that, "White men are not invited to the feast at Alcatraz", an inversion of the traditional thanksgiving myth of sharing the feast.

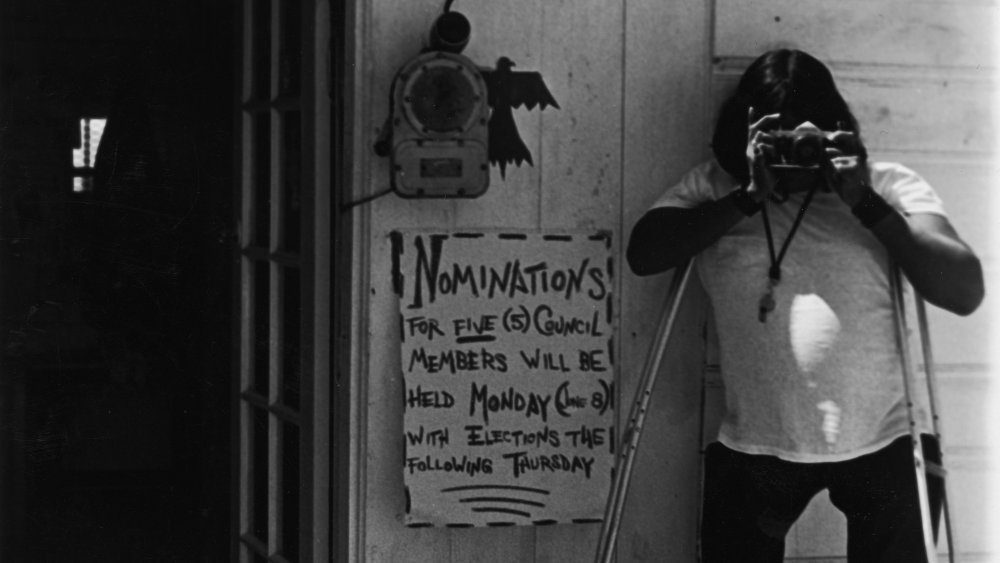

The organizers quickly got to work, setting up an elected council and providing everyone with a job. According to Teen Vogue, they also set up a school, a clinic, housing, as well as a place to hold the inipi ceremony, a purification ceremony for the Lakota people. In another reversal, the Indians of All Tribes created their own Bureau of Caucasian Affairs, which required all whites entering the island to register beforehand.

The director of the National Council on Indian Opportunity (NCIO) went in to try to negotiate on behalf of the federal government, with the paltry suggestion of building a park on the island for Natives. But for the Indians of All Tribes, their demands were clear: a cultural center, a museum, and a university for Natives.

Radio Free Alcatraz spreads the sound of resistance

During the attempted reclamation and occupation of Alcatraz, Santee Sioux activist John Trudell, a member of the occupation, created the pirate radio station Radio Free Alcatraz. According to Narratively, over 100,000 listeners, Native and non-Native, would tune in to stations in New York, California, and Texas. People would hear not only updates about the protests and reclamation but examples of governmental infringements of Native rights, historical as well as contemporary, as well as advocations of Native self-determination.

For many people, Native and non-Native, this was the first time such issues were being discussed out in the open. And for many non-Natives, this was the first time they were exposed to the true history of their country. It's no wonder that the FBI's dossier on Trudell would run over 1,000 pages.

It was because of Radio Free Alcatraz that Trudell was able to garner so much support from celebrities such as Marlon Brando and Jane Fonda. Musical groups like the Grateful Dead and Creedence Clearwater Revival donated money and food and even held a concert off the coast of Alcatraz on a boat, donating the boat afterward. Radio Free Alcatraz persevered through bad weather and spotty electricity, but the broadcasts came to an end when the federal government shut off all electricity and radio services on the island.

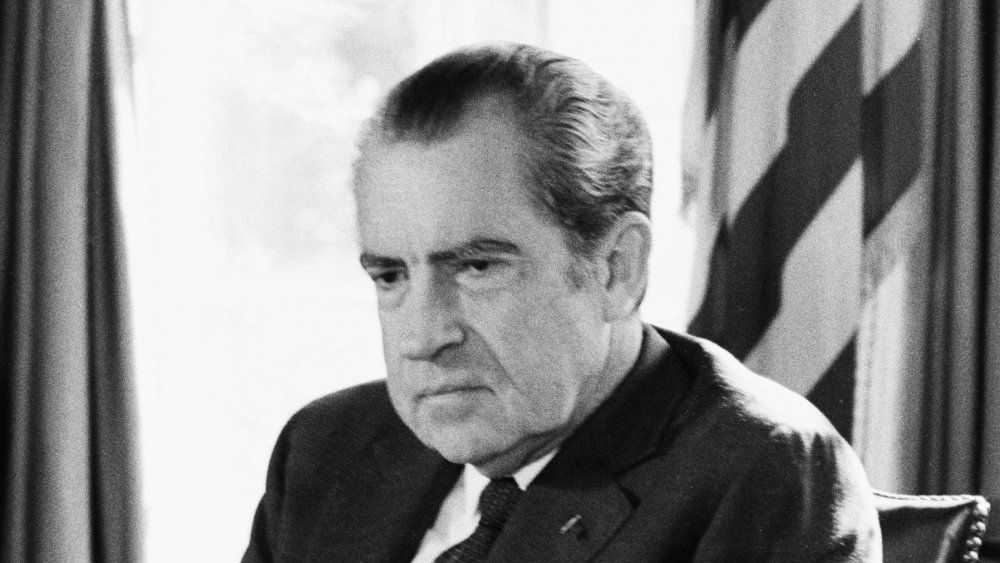

Nixon's alleged noninterference

For a time, President Richard Nixon's policy was one of noninterference. According to Al Jazeera, Nixon had worried about the risk of families getting injured in a military invasion of the island and initially held back on sending in troops. The events of the reclamation of Alcatraz also coincided with the Kent State shootings in May 1970, when the National Guard shot and killed four students, injuring nine others, and Nixon's advisors suggested that in the event of a repeat occurrence, the blowback would be too great.

This noninterference didn't extend to Coast Guard blockades, which frequently seized supplies and turned away boats filled with supporters. And as time went on, patience wore thin, and the federal government went on to cut the electricity, radio, phone lines, and fresh water supplies in their attempts to drive the Native people out. In the end, the federal government was mostly biding its time, hoping that public support would peter out and that people would leave by themselves.

However, Nixon did attempt to appease the occupiers, leading to significant reform in Native legislation. During the attempted reclamation, Nixon ended the Indian Termination policy, another iteration of assimilationism which had been started by Eisenhower, and introduced new legislation toward Native self-determination. Nixon's administration had warned him that what was happening at Alcatraz was symbolic, stemming from injustices that were not rooted in that one piece of land, and from his actions, it seemed as though he was not completely oblivious to it.

Untimely tragedies as the struggle continues

In January 1970, Richard Oakes' 13-year-old daughter Yvonne fell to her death in a tragic accident. Reeling from the loss, Oakes and his family left the island, leaving the community to react to two losses while trying to fill the vacuum of leadership he had left. Her death coincided with the departure of many students, who returned to their universities in order to keep from losing their scholarships.

Per Narratively, with rumors swirling that US Marshals were threatening to raid the island at any minute, the occupiers' spirits began to falter. War Jack and Trudell tried to continue leading the movement, and while they initially worked well as a team, they would grow to increasingly distrust one another. The United States government was also unproductive in negotiations, putting their efforts into sowing distrust more than decisiveness.

As news of a power struggle and misuse of donated funds were reported in the media, public opinion began to change. There were also reports of drug problems on the island, some of which were brought in by the non-Natives from the San Francisco hippie culture.

Intimidation and infiltrators on Alcatraz Island

By the end of May 1970, all electricity had been shut off at Alcatraz. The federal government also removed the water barge, effectively cutting off all access to clean water, and shut off the telephone lines in further attempts to pressure people into leaving the island willfully.

Three days later, several fires broke out around the island, according to the National Park Service. Several buildings were destroyed, including the warden's quarters, the doctor's quarters, and part of the lighthouse. While the government blamed the Natives for the fires, protesters on the island claimed that a group of white infiltrators had set the fires on purpose, possibly in another attempt to turn public opinion against the protesters.

Despite the lack of water and electricity, dwindling access to supplies, and vacillating support from the public, the Indians of All Tribes held fast. It would take another year to physically force the last of the occupiers off the island.

Dwindling public support and the final forcible removal

The lack of electricity on the island, shut off by the United States government itself, meant that the lighthouse and fog signals on Alcatraz weren't working. According to PBS, this led to public concern about navigational safety in the bay. However, occupiers refused to let the Coast Guard onto the island to fix the navigational aids unless fresh water access was restored.

At one point, some occupiers began stripping copper wires and tubes to sell as scrap metal, in an effort to raise money for food. As a result, three Natives were arrested, tried, and found guilty of selling 600 pounds of copper. This destruction of property led the media to turn on the occupiers, and they began to run primarily stories of the copper trial as well as alleged violence and assault on the island.

The final straw occurred in mid-January 1971, when two oil supertankers collided in the nearby bay. Despite the fact that ultimately, the lack of light from Alcatraz bore no fault for the collision, the public had made up their minds. As food supplies dwindled and conditions on the island worsened without water or electricity, Nixon developed a plan to remove the last of the Native occupiers. On June 10, 1971, 15 unarmed Natives, four of whom were children, were removed by FBI agents, armed federal marshals, and special forces police.

The worldwide impact of the attempted reclamation of Alcatraz Island

The effect of the occupation of Alcatraz was almost instantaneous, a catalyst that ignited protests by indigenous people from all over the world, each one galvanizing the other. According to Al Jazeera, these protests spanned the entire globe, stretching from Norway to Australia. Protests by the Māori people in New Zealand, for example, led to the passage of the Treaty of Waitangi Act of 1975, leading to a process that attempted to address Māori grievances.

According to Canadian Geographic, the '70s would also see a period of Métis grassroots activism in Canada, as organizations in Manitoba and Alberta fought against social and institutional discrimination. Indigenous women were also on the front lines in Saskatchewan, forming the Saskatchewan Indian Women's Association, which provided education, birth control, and counselling.

In 1974, the World Council of Indigenous Peoples was created, establishing a global network for the first time. Although it was dissolved in 1996, the council was instrumental in bringing the advocacy of indigenous rights to the international stage.

The lasting impact of the occupation of Alcatraz

While the attempted reclamation of Alcatraz ended in a solemn departure from the island, it can hardly be considered a failure. Though the island itself remained in the possession of the United States government, Nixon ended the termination laws and granted Native people self-determination with the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, among many other pieces of legislation, according to Teen Vogue.

Nixon also returned Blue Lake to the Taos people, along with almost 50,000 acres, and contributed a grant of land near Davis, California, toward fulfilling some of the occupiers' demands. As a result, Deganawidah-Quetzalcoatl University was founded, and UC Davis started offering a doctorate in Native American studies, the first US university to do so. The attempted reclamation of Alcatraz inspired several other movements, including the Trail of Broken Treaties, which was a series of protests that traveled across the country before reaching Washington, DC, and occupying the Bureau of Indian Affairs for six days.

To this day, people gather at Alcatraz, now a national park, to celebrate "Unthanksgiving Day," in the spirit of the island's own first Thanksgiving, as a time of remembrance for the injustices committed against indigenous people. The tactics used at Alcatraz were taken up in 2016 by protesters at Standing Rock. The spirit of resistance that rose up at Alcatraz was one of a movement that continues to fight against injustice and oppression.