The Legend Of The Headless Horseman Explained

At Halloween, you need the essentials: jack-o'-lanterns, candy corn, and incessant replays of the novelty pop jam "Monster Mash." You'd also be remiss to leave out the Headless Horseman, the galloping ghoul of folklore fame. The Headless Horseman has captured our imaginations for centuries, materializing everywhere from Kanye West lyrics to a Tim Burton adaptation, stage musicals, and silly Disney cartoons.

Easily the most popular version of the beheaded equestrian is from Washington Irving's "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," which introduced an early American audience to a goblin rider menacing the tranquil roads of a quiet New York village. In fact, today, the town of Sleepy Hollow has made the Headless Horseman something of a town mascot – he appears on fire trucks, sports jerseys, and imposing town sculptures.

While Sleepy Hollow fans might have made the Headless Horseman synonymous with Halloween horror, the empty-shouldered ghoul has a much broader range. This decapitated rider has cantered through Scandinavian mythology, early German folklore, and northern Indian lore. Here's the history of the odd global phenomenon of headless riders and just how, precisely, they lost their precious heads.

The Headless Horseman is from the Middle Ages

One of the first mentions of the Headless Horseman can be traced all the way back to the Middle Ages. Among the most prominent is the Irish legend of the "Dullahan" or "Gan Ceann," which, as told by History, is something of a Grim Reaper figure. In other words, he's fierce, terrifying, and out to harvest souls. The Dullahan, a dark faerie, is closely associated with the Celtic god Crom Cruach, the Dark God of the Burial Mound, per The Vintage News. (Other sources state Crom Dubh.) When Ireland stopped doing sacrifices for their dark god around the sixth century, the legend of a headless horseman trotted in as a substitute.

The Dullahan holds his own grinning head, which sometimes glows, to see at a great distance. The gruesome rider gallops around on a black horse with a whip — or sometimes, in a carriage drawn by six horses. The Irish Place explains that if you are to look at the Dullahan, you will immediately be blinded. If you hear the dreadful faerie speak your name, then sorry, you've been chosen as his next victim to die. He's a rather nocturnal ghoul. The Irish believe the Dullahan hunts for lives on festival days after sunset. Not a door or lock can keep this horseman away — except if you put gold coins at his feet. The Dullahan is a popular fixture of Irish mythology and one of the most demonic depictions of a headless horseman.

The Brothers Grimm recorded headless horsemen

The Brothers Grimm recorded German tales depicting a headless rider dating back to the 1600s. At the beginning of these stories, says World of Tales, the Brothers Grimm explained the legend: Any man who commits a crime that deserved to be punished by beheading during his lifetime will be condemned to be headless in his afterlife. In the tale "Hans Jagenteufel" from Dresden, a woman is gathering acorns near a part of the forest called "Lost Waters" when she hears a hunting horn and then a thud.

The woman turns to see a rider standing over her, with a gray horse and gray cloak. The woman thinks nothing of it and continues her acorn collecting. The next day, in the woods, the woman is met by this same horseman — only this time, he's carrying his own head. The rider calls himself Hans Jagenteufel, asks if she took the acorns without permission, and tells the woman that when he was young, he drank excessively and took as he pleased. That life of sin had condemned him to an afterlife as an evil spirit. This German version makes the Headless Horseman something of a cautionary tale. The Headless Horseman is a warning to the living to avoid his wicked fate: Don't steal.

The Headless Horseman as the Wild Huntsman

The character of the Wild Huntsman — another German take on the Headless Horseman — has cropped up many times in the works of Sir Walter Scott, Gottfried Burger's "The Wild Huntsman," tales collected by Karl Musäus, and those good old Brothers Grimm. As the legend goes, in Brunswick, a man named Hackelberg is so devoted to hunting that, as he dies, rather than go to Heaven, he begs God to keep him on Earth to hunt. Hackelberg then became the Wild Huntsman, roaming the woods with his fiery hounds on an eternal hunt.

According to Mythology & Fiction Explained, if a hunter hears the thunderous horn of the Wild Huntsman, they should not go hunting on the following day. For Germans, the Wild Huntsman portended hunting accidents, and he even served as a vengeance figure. If he came upon them in the woods, the Wild Huntsman would seek out those who had wronged others so he could punish them.

The Headless Horseman spooks his Scottish clan

Like many headless horsemen, Scotland's supernatural rider was born in battle.

Scottish legend has it that in the valley of Glen More (which cuts across the Isle of Mull) in the 16th century, there was tension in the Maclaine clan. As a Scottish writer at the Hazelnut Tree recounts, Iain Og, the clan chief, found himself in a dispute with his son Ewen after he denied him property. In 1538, the two planned a mass duel. However, the day before the duel, Ewen came upon a fairy washing blood out of clothes who predicted that if his servant failed to serve him butter at breakfast the following day, he would not survive the duel. Sure enough, butter failed to be on Ewen Maclaine's breakfast table.

In the duel, one of Iain's followers beheaded Ewen. Ewen's horse, terrified, sprinted away with just Ewen's body strapped in the saddle. Ever since, the specter of a body riding on a black horse has haunted Glen Moore. It's said that if a member of the Maclaine clan sees the headless horseman, it's foretelling an imminent death in their own family. You could say that a headless horseman roaming the calm clearings of your hometown isn't exactly an ideal family inheritance.

The Headless Horseman in Indian folklore

Not all crownless jockeys have menacing histories. In Indian folklore, the Headless Horseman is actually a heroic figure. According to legends from the Indian states of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, the jhinjhār is known as a prince who lost his head while defending his village from bandits or highwaymen, per the History Goes Bump podcast. On the other hand, the Woodland Horse Center suggests that the jhinjhār could have been a Mughal cavalryman defending his prince.

These spirits represent those who had wrongful deaths and come back to protect the innocent. Battling either on or off their steeds, these well-meaning spirits are defenders. For those who encounter them and are vulnerable, they'll do no harm. But what if you actually wanted to get rid of this benevolent rider? The jhinjhār supposedly can be repelled by powdered indigo dye. The indigo dye puts the jhinjhār's spirit at ease, and he disperses.

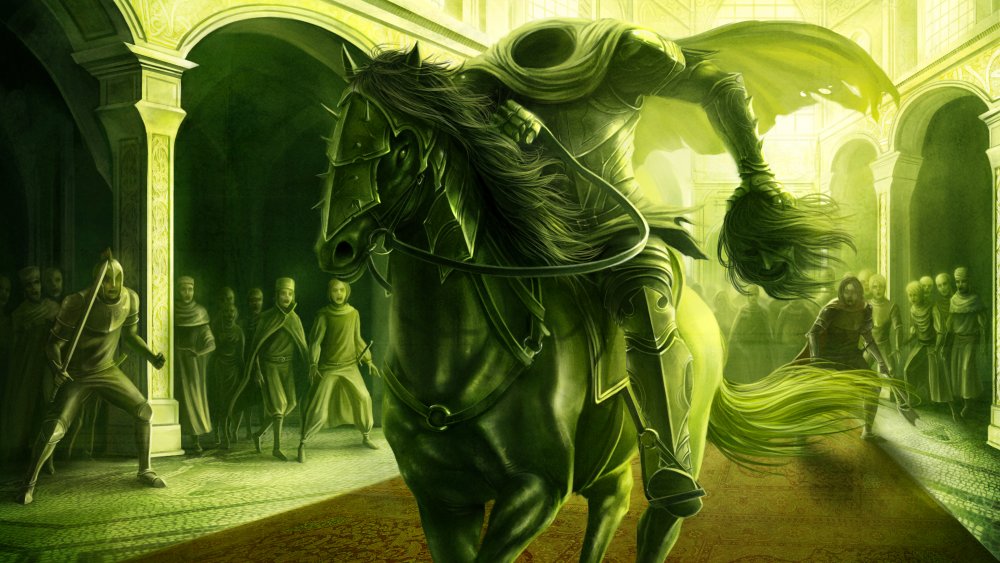

The Green Knight was headless

"Sir Gawain and the Green Knight", a 14th-century Middle English chivalric romantic poem by an anonymous author, also has a cameo from a headless rider. As Newsweek tells it, a green-cloaked, gigantic figure on a green horse arrives at Camelot on New Year's Day. This Green Knight challenges anyone in King Arthur's court to strike him with a blow, under the condition that in exactly a year, the Knight will return the strike. Sir Gawain, a knight of King Arthur's Round Table, takes up the contest. He beheads the Green Knight, but to his horror, the Green Knight simply picks up his own head and remounts his horse.

What ensues is a test of Sir Gawain's honesty. As Gawain awaits his battle with the Green Knight, he rests at the castle of Lord Bertilak de Hautdesert. When the fated day comes, the Green Knight tests Gawain's nerve by striking him with three blows in the neck. However, they leave Gawain almost unscathed. In the end, the Green Knight was, in fact, Lord Bertilak de Hautdesert, who had been magically transformed into a headless giant. This headless horseman tale sets itself apart from the rest, as it uses a "beheading game" to test the loyalty of its main character. This green and tremendous decapitated horseman is immortal, mysterious, and ultimately a harmless litmus test for King Arthur's knights.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

Most American audiences know the Headless Horseman through Washington Irving's "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," published in 1820. Irving set his gothic classic near present-day Tarrytown, New York, and as his story goes, schoolteacher Ichabod Crane arrives at Sleepy Hollow and hears the local Dutch legend of a ghostly headless Hessian soldier who haunts the Old Dutch Church. The superstitious Crane laps up these tales of the beheaded, galloping ghoul. He also falls for local 18-year-old heiress Katrina Van Tassel, but he has a romantic rival — the burly Brom Van Brunt.

After a feast hosted by the Van Tassels one night, Crane sets out on the spooky ride home on a borrowed horse — only to notice a shadowy figure alongside him. "He appeared to be a horseman of large dimensions, and mounted upon a black horse of powerful frame," Irving wrote. Much to Crane's horror, he sees that the horseman's head is resting on the pommel of his saddle.

The Headless Horseman hotly pursues Crane until they approach the church said to be the rider's burial place. Rising in his stirrups, the Headless Horseman throws his head at Crane, knocking him out. The next morning, a search party finds only a trampled saddle, Crane's hat, and a smashed pumpkin. Crane has vanished. The ending of the tale is ambiguous, with Irving suggesting that the shadowy rider might have been prankster Brom Van Brunt.

The Headless Horseman's connections to the American Revolution

Washington Irving's tale of the town of Sleepy Hollow, terrorized by a mysterious headless equestrian, is said to have its origins in the American Revolution and Dutch traditions of New York, according to Folklore Thursday.

During the American Revolution, German mercenaries fought alongside the British troops. In fact, the battle of White Plains was a mere eight miles from the town of Sleepy Hollow, where Irving wrote his ghastly tale. As told by The New York Times, by name-checking the Hessian soldiers of the American Revolution, Irving conjured a familiar fear for contemporary readers. The German auxiliary troops had been known for being particularly merciless in battle, killing their hostages and bayoneting retreating militia.

As Irving wrote of the tranquil town in "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," the place seemed under some "witching power, that holds a spell over the minds of good people." In fact, spooky locations he names in his tale, like Major John André's Tree, are actually existing remnants from the war for American independence. That specific tree, where Ichabod Crane first sees the horseman, marked the place where Major John André, a courier for the traitorous Benedict Arnold, was captured by local farmers and turned over to General George Washington, per The New York Times.

The Old Dutch Church, where Irving's Headless Horseman was said to be buried, is the final resting place of many Revolutionary War heroes.

The headless Hessian soldier may have existed

What of the imposing figure of the black-cloaked Hessian soldier? Is it even possible that Washington Irving's ghostly villain was based on a real person? As we know, during the American Revolution, German mercenaries fought alongside the British. On September 17, 1776, Hessians joined the Brits in the Battle of Manhattan, where the colonists fled in terror of their ruthless bayonets. The Hessians rode again on October 28, during the Battle of White Plains.

Per Folklore Thursday, General William Heath, an American general who oversaw these battles, later wrote, "an artillery shell took of the head of a Hessian artillery man." (Other sources quote General Heath differently, but the gist is the same.) As reported by the River Journal Online, "One of the artillery horses was also left dead on the field." Heath's journals were published in 1798, making it entirely plausible that Washington Irving paged through these descriptions. A head shattered by a cannonball and a fallen horse make for a great ghost story. Could this be the same headless Hessian who was buried in the Old Dutch Churchyard in Sleepy Hollow? Some historians believe so. In fact, this tale is likely so closely tied with Halloween because the battle of White Plains took place just a few days before October 31.

There was a real Ichabod Crane

Many of the people visited upon by headless horsemen throughout the various legends are seen as arrogant, scheming, or downright foolish. Was there any inspiration for the weak-spirited, bookish Ichabod Crane of Irving's story? It turns out, Washington Irving was all about recycling a good Yankee name when he heard one. There was a Colonel Ichabod Crane who served Governor Daniel D. Tompkins during the War of 1812 and went on to serve in the military for 45 years. As reported by The New York Times, although Crane and Irving could have possibly crossed paths while serving at Fort Pike, it's unlikely that Irving asked permission to use his moniker for a gangly schoolteacher.

In fact, schoolteachers Jesse Merwin and Samuel Youngs may have been the true inspirations for the visiting Connecticut schoolmaster. Youngs was a good friend of Washington Irving, and he was initially buried at the Old Dutch Church. Merwin, meanwhile, taught in Kinderhook. New York, where there is a surviving old schoolhouse bearing the name Ichabod Crane Schoolhouse.

The appearance of the Headless Horseman

The image of the Headless Horseman most familiar to us is that of the ghostly Hessian soldier, clad in his uniform, with a black cloak, carrying his own head on his saddle. Monumental in size, the Hessian rides so swiftly that he's compared to the wind.

While uniquely terrifying in its own right, Irving's equestrian looks downright kid-friendly compared to Irish folklore's Dullahan. According to Dullahan.com, the Dullahan holds his own head high up, which bears a hideous grin, small black eyes, and the smell of molding flesh. This Irish demonic fairy rides on a great black horse — which itself is sometimes headless — or in a black carriage drawn by six horses. This ferocious creature also carries a whip made out of a human spine and a bucket of blood in some versions of the folklore, as if he weren't already frightening enough.

The headless horseman of Germany is often clad in gray and in hunting gear. In Scandinavian folklore, the ghost rider sits upon a white horse, with his head under his left arm, and is joined by black dogs with fiery breath. Celtic horsemen, meanwhile, are usually in all black and ride horses that are equally cranially challenged. While the variations of the Headless Horseman might have different getups, sidekicks, and forms of tormenting their locals, they all share one thing in common: The Headless Horseman wants his head back.

What headless horsemen represent

So, how come so many decapitated cowboys have popped up in literature across continents throughout the centuries? Humans know how to brood. Like the horseman doomed to endlessly search for his head, humans are prone to obsess about the past and their losses and are overpowered by their betrayals.

Franz Potter, a Gothic studies professor at National University, told History that these supernatural beings usually symbolize the past which still haunts the living. "The horseman, like the past, still seeks answers, still seeks retribution, and can't rest," said Potter. "We are haunted by the past which stalks us so that we never forget it."

That's why you see headless horseman legends often arising in cultures in the wake of wars, loss, and pestilence. For example, the Dullahan legend first came into prominence in the sixth century, once Ireland was Christianized and ceased their sacrificial rituals to the god Crom Dubh, as told by The Irish Place. Likewise, Irving's Headless Horseman spoke to the residual horrors of the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and, as explained by Smithsonian Magazine, the then-recent yellow fever epidemic. Like a contagion hanging over the town of Sleepy Hollow, or the remote villages of Germany, the threat of the Headless Horseman is a reminder of our histories that just won't go away.