The Legend Of The Yeti Explained

You may have seen him in storybooks or in video games, on Scooby Doo or in Monsters, Inc. And even if you've never traveled outside of the US, you know him: the yeti. (You might call him the Abominable Snowman, and we'll actually talk about that name and why it's a pretty big deal in the history of yeti lore.) Sure, you can picture him — a hulking, white-furred creature capable of breaking a man in half then probably eating him afterwards. Would you be surprised to find out that's a fairly recent addition to the story?

The yeti is actually one in a family of creatures: they're the ape-men, and Americans have one that lives much closer to home. He's called Bigfoot, or Sasquatch, but the idea is basically the same. The yeti is reclusive, mysterious, and intelligent, and he lives in remote areas throughout the Himalayas. That's a good thing — according to the BBC, one of the traditional tales told by Sherpas is that as the sun rises, the yeti will grow bigger and stronger. And anyone who's unlucky enough to see him? That person will get weaker and lose consciousness. It's unclear what happens to them after that, and honestly... that's probably for the best.

Let's talk about the yeti: the creature behind the mystery.

The English-speaking world only learned about the yeti in the early 1800s

Even in Western culture, tales of the yeti are so widespread, it seems like he's been a part of Western lore forever... but he's a fairly new addition.

According to Daniel Capper, PhD., an Associate Professor of Religion at the University of Southern Mississippi, the first mention of the yeti in the English-speaking world came from Brian H. Hodgson. Hodgson was a representative of the British, living at Kathmandu's royal courts between 1820 and 1843 with Nepalese assistants who told him the first stories of the yeti. Back then, he was described as a "wild man [who] moved [...] erectly; was covered with long, dark hair, and had no tail."

It wasn't until 1889 that a Major Lawrence A. Waddell reported finding the wild man's footprints, and then, sometime around 1904, there was the first sighting. William Hugh Knight, a British soldier stationed near the Indian city of Gangtok said he saw the creature — who, he added, fortunately didn't see him. He described it in 1921, telling The Times: "He was a little under six feet, almost stark naked in that bitter cold [...] He was a kind of pale yellow all over, [...] a shock of matted hair on his head, little hair on his face, highly splayed feet, and large, formidable hands. His muscular development in his arms, thighs, legs, back, and chest were terrific."

Every continent except Antarctica has legends of a 'yeti'

There's something incredibly enduring about the idea of the ape-man; do some digging, and it turns out that every continent has their own version of him (except, of course, Antarctica).

In Australia, says National Geographic, he's called the Yowie. He's the Yeren in China, the Ferles Mor in Scotland, in Sumatra he's known as the Orang Pendek, and in Brazil? There, they call him the Mapinguari.

In Russia, their mysterious, yeti-like creature is called an Almasty, and in the 1870s, local landowners in a remote part of the Caucasus region of Russia claimed they had caught one. They named her Zana, and kept her captive for years — during which time she was described as "very big, strong, her whole body covered with hair." Zana gave birth to four children during her captivity, and some of her descendants are still alive today. In 2013, University of Oxford Professor of Human Genetics Brian Sykes tested samples of her living descendants' DNA, along with DNA taken from the tooth of her son. Contrary to claims that she was a Neanderthal or an Almasty, he found (via Channel 4) that she seems to have been 100 percent sub-Saharan African. Examining the skull of her son, Khwit, he found there were some ancient characteristics (like an elevated brow ridge), suggesting she was perhaps "a remnant of an earlier human migration out of Africa." And not an Almasty.

Tibetan beliefs tell of yetis who have participated in Buddhist rituals

Go back to the older, Tibetan tales of the yeti and you'll find something incredible: they were invaluable participants in the Buddhist faith.

According to Professor Daniel Capper, stories include ones like that told by Lama Sangwa Dorje, a 17th century Sherpa religious leader. He wrote that as a young man, he decided he wanted to found monasteries through the Khumbu region. Seeking guidance, he retreated to a cave and began to meditate. It's typical for people to provide meditating religious men with food and water, but Sangwa Dorje's carer was a yeti. Not only did the yeti bring him food, water, and fuel for his fire, but he also started learning the ways of Buddha, and became a disciple. When the yeti died, Sangwa Dorje kept his scalp and a hand, moving the sacred relics to a place of honor in the monastery of Pangboche Gompa.

His story isn't the only one of devout yetis: in Bhutan, it was believed that in the middle of the night — when all humans were gone and sleeping — yetis would care for a temple devoted to Panden Lhamo, a protection deity. They would steal in under the cover of darkness, clean and refill offering bowls, make sure the lamps were full, and disappear before the sun rose and the people returned.

Yetis were originally very nice

According to Professor Daniel Capper, the original yetis of the Himalayan region were actually super nice. Temple art in Tibet depicts them as happy, smiling creatures that are very human-like, and there's a ton of stories about the kindness of individual yetis — even likening them to bodhisattvas, Buddhist figures who devote their lives to ending suffering and helping others achieve enlightenment.

Yetis were well known in the Himalayan countries for helping travelers lost in the mountains, and repaying kindness with kindness. They're considered not fully human, but something more than animal, too: in artwork depicting the pattern of rebirth and reincarnation, many meditational artworks show the yeti existing in their own separate category below humans yet above animals, capable of thought and kindness.

So, why does the West think of the yeti as a monster? In 1921, a journalist named Henry Newman interviewed members of an expedition to Mount Everest. They told him of the "metoh-kangmi" their guides spoke of. The word, LiveScience says, actually means "man-bear snow-man," but Newman translated it as "filthy snowman." He didn't particularly like "filthy" so he changed it to "abominable," people ran with it, and suddenly, the yeti was not-so-nice.

The Lepcha see the Yeti as something very different

The Lepcha are a group of people who live in eastern Nepal, western Bhutan, and West Bengal in India (via Britannica). They, too, tell tales of the yeti, but for them, he's a little different. According to Transcultural Encounters in the Himalayan Borderlands, the Lepcha give the yeti another name: Chu Mung, or "Glacier Spirit." Chu Mung is their god of the hunt and the creatures of the forest.

Research done by Kerry Little of Sydney, Australia's University of Technology uncovered traditional Lepcha stories, including tales of the yeti. After Lepcha hunters kill a deer, they perform a ritual: they cut off one hoof, an ear, and the tongue, remove the kidneys and heart, and drink some of the deer's blood while it's still warm. The pieces of the deer are wrapped in leather and offered to the god of the hunt, for a few reasons. First, they hope the offering will please him, and they'll have a successful hunt next time.

Secondly? Ancient belief says that a kill left in the forest overnight will be reclaimed by the yeti — or Chu Mung — who will bring it back to life. He can't resurrect a creature that isn't whole, so the hunters remove pieces of the animal. There are also tales of families taking foundlings into their home, only to have them grow up very, very quickly: those that are kind receive blessings, and those who aren't kind? They pay the price.

The Nazis once went yeti-hunting

In the early 1930s, a young zoologist named Ernst Schäfer was living the high life as what Der Spiegel described as "the Indiana Jones of zoology," courted by both the US and Germany for his scientific and hunting know-how. In what he later called his "biggest mistake," he chose... poorly. He was summoned back to Germany in 1936, and threw in with Heinrich Himmler.

Himmler brought him into contact with the Ahnenerbe Society, who believed in a "Nordic-Atlantic original culture" that had been destroyed when a moon collided with the earth. They also believed that remnants of this race survived in the Himalayas, and soon mounted and funded an expedition to — at least, in part — find remnants of that race. For his part, Schäfer was more interested in the zoological knowledge that was still largely hidden in Tibet, and here's where we get into yeti territory. The expedition returned to Germany with thousands of dead birds, eggs, pelts, insects, and artifacts — along with, says The Guardian, a taxidermy bear that was believed (but only by some) to be proof of a yeti.

Did the Nazis really believe it was? No, says Texas A&M University's Jorge M. Gonzalez. Schäfer spent a good bit arguing that it wasn't a yeti at all, but a Tibetan bear. There's no word on how bummed Hitler was.

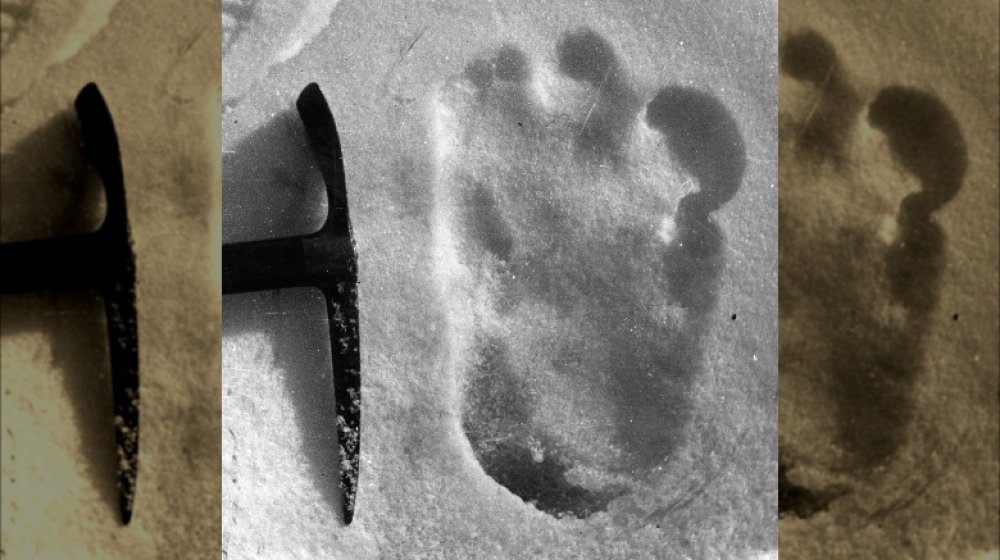

The 'best' photo of a yeti print was taken by a well-respected mountaineer

When you take a step back and look at the story, the idea of a mysterious ape-man living in the Himalayan Mountains is... well, pretty unbelievable, right? So why has it been so popular for so long?

Part of the reason, says National Geographic, is that the most famous photo of a yeti footprint wasn't just very real, but it was taken by a well-respected mountaineer. In 1951, the British explorer Eric Shipton was on the Menlung Glacier (west of Mount Everest) when he snapped a photo of a strange-looking — and huge — footprint. It was incredibly sharp, about 13 inches long, and definitely looks like a footprint... made by a foot with a thumb. And since it was Shipton — who, The New York Times says, had a long career scaling mountains across Nepal, Africa, and South America, then chronicling his adventures in eight books — who took the photo, no one questioned it.

So, what was the photo? Daniel Taylor, author of Yeti: The Ecology of a Mystery, has been to Nepal and has seen similar footprints. Local hunters told him it was likely from a tree bear, a particular species of bear that has a thumb-like appendage from years of living in trees, breaking bamboo, and holding branches.

The Daily Mail tried to find it... and didn't succeed

After Edmund Hillary's party finally succeeded in climbing Mount Everest, a certain type of media outlet turned their attention elsewhere: the mysterious yeti that was rumored to live there. In 1953, a journalist named Ralph Izzard partnered up with The Daily Mail to mount an expedition to find the yeti, and according to Bigfoot: The Life and Times of a Legend, the whole thing was reported by other papers as a bit of a joke.

Izzard and eight others headed off into the Himalayas for 16 weeks, into some of the most difficult terrain in the world. To his credit, he included scientists and mountaineers, along with 12 Sherpas and 200 porters. They sent out a scout party, too: Dr. Charles Stonor headed out first, and must have been very excited when he met a local who claimed to have had a run-in with a yeti just three months earlier. He believed the stories, saw what he thought were tracks, and the team followed — complete with a flag bearing the cartoon image of "Bing the Snow-Baby."

When they returned, they had no actual evidence — although some of the party members were convinced they'd seen enough footprints and heard enough stories to say without a doubt that it was real. Others were less impressed by the circumstantial evidence, and The Daily Mail? In 2018, they're still running articles about the expedition with titles like "Lies of the Yeti hunters."

That super strange time Jimmy Stewart became a stolen yeti hand smuggler

In the 1990s, yeti relics disappeared from the Pangboche Monastery. Just what happened to them is a weird, weird story... so buckle up.

According to the BBC, Westerners first realized the yeti relics were there in the 1950s, when a group on an expedition to find a yeti stumbled across the monastery — and reported that the yeti scalp was likely goat or antelope, but the hand didn't look anything like a human or primate's. Peter Byrne, leader of the 1957 expedition, negotiated with the temple monks: he would take one of the fingers, and in return, he'd give them a human replacement finger and a hefty donation to the temple's upkeep. But getting it out of the country and back to England proved difficult, and Byrne needed to smuggle it first into India, then find some way to get it back to London. The answer, says Atlas Obscura, was the underpants of a movie star's wife.

More specifically, she was Gloria Stewart, the wife of Jimmy Stewart. They were on vacation in Calcutta, and she put the finger in her lingerie case — which British customs officials were way too proper to search. The finger didn't get analyzed until 2011, and the DNA? Human.

There's a sad footnote to this, too: after a 1990s documentary mentioning them ran in America, the hand and scalp were both stolen from the monastery. Mike Allsop, a pilot from New Zealand, tried making amends by presenting the monastery with a replica made by Weta Workshop (of Lord of the Rings fame) in hopes of allowing the temple to once again use it to attract visitors.

Bhutan has a national park set aside for the protection of their yeti

Bhutan is nothing short of breathtaking, and as High Country News notes, it's sometimes called "the last Shangi-la." And they're doing their best to preserve some of the most unspoiled of their natural landscapes... with help from the yeti.

In 2003, Bhutan set aside a 650 square kilometre protected area called the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary. They did it with the help of a $700,000 grant from the MacArthur Foundation (given via the World Wildlife Fund), and the specific reason for setting up that particular reserve was given as protecting "the habitat of the Yeti, known in Bhutan as the migoi, or strong man."

For real? Well... yes, although even their official site says they protect "even the mythical Yeti." And here's the thing — they're also protecting the habitat of species like the snow leopard, barking deer, the Assamese macaw, the red panda, and the Himalayan black bear. So, why not throw the yeti in there, too? You know... just in case.

What about some of those pieces of physical evidence?

Even though a representative of the Western world has yet to sit down with a yeti over a cup of tea and some nice biscuits (on the record, at least), there's been a ton of evidence collected in the form of things like hair and teeth. We have the capability of doing DNA testing now, so have we? Absolutely!

In 2013, a University at Buffalo geneticist got a call from Animal Planet, who was working on putting together a science-based investigation into the yeti. Charlotte Lindqvist jumped at the chance, mostly because she suspected much of the "evidence" came from wild bears, and wild bears aren't easy to get a DNA sample from. According to The Atlantic, Lindqvist did a DNA analysis on nine samples that ended up being a thigh bone from a Tibetan brown bear, a dog's tooth, hair of a brown bear, and various other bits of brown bears and one lone Asian black bear.

What did Animal Planet think of the results? Lindqvist says, "When I had to reveal to them that okay, these are bears, I was excited about that because it was my initial motive to get into this. They were obviously a little disappointed."

The search for the yeti has yielded some surprising scientific research

Spending a boatload of money on doing some DNA sequencing to find out whether or not some bones really are from a yeti might seem like a massive waste of money, but it's actually incredibly important — and here's why. When the University at Buffalo's Charlotte Lindqvist carried out her DNA study on supposed yeti relics and discovered they were from various types of bears, it was a huge deal. National Geographic says that while collecting, studying, and sequencing "yeti" remains, Lindqvist was actually building up a genetic profile of local bears — which could, in the long-term, help scientists and conservationists better understand how to protect them.

They also learned a ton about the critically endangered Himalayan brown bears (pictured): specifically, they discovered they're much older than other types of brown bears, and split from the evolutionary tree around 650,000 years ago. That awesome bit of knowledge came because, for the first time, they were able to build a complete mitochondrial genome of the rare bear species, and that's pretty darn cool.

So, while they didn't find evidence of a yeti, they did find something else just as elusive... and we like to think that the old yeti — the friendly yeti, the yeti of the forest and the hunt — would be proud of that.