The Truth About The Unabomber

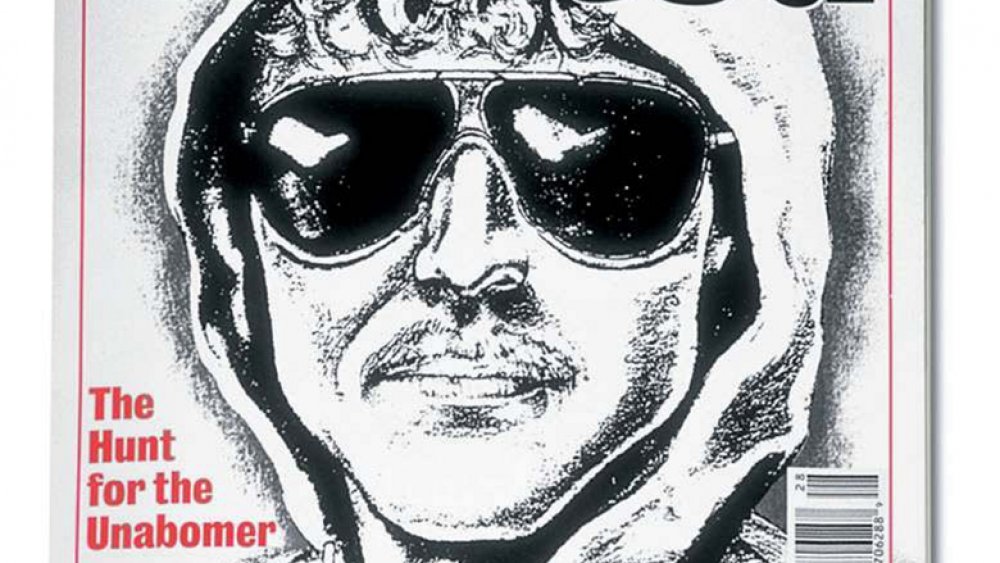

For nearly two decades, the unknown subject in aviator sunglasses and a hoodie in the now-famous police sketch unleashed a reign of explosive terror on the United States. He maimed nearly two dozen innocents, killed three more, and expertly and repeatedly eluded capture all the while. The media dubbed him the "Unabomber," and it would eventually publish his lengthy manifesto against technology, Industrial Society and Its Future. Ultimately, it was the Unabomber's 35,000 words on the evils of technology that would put an end to his acts of terrorism, lead to his capture, and reveal his true identity.

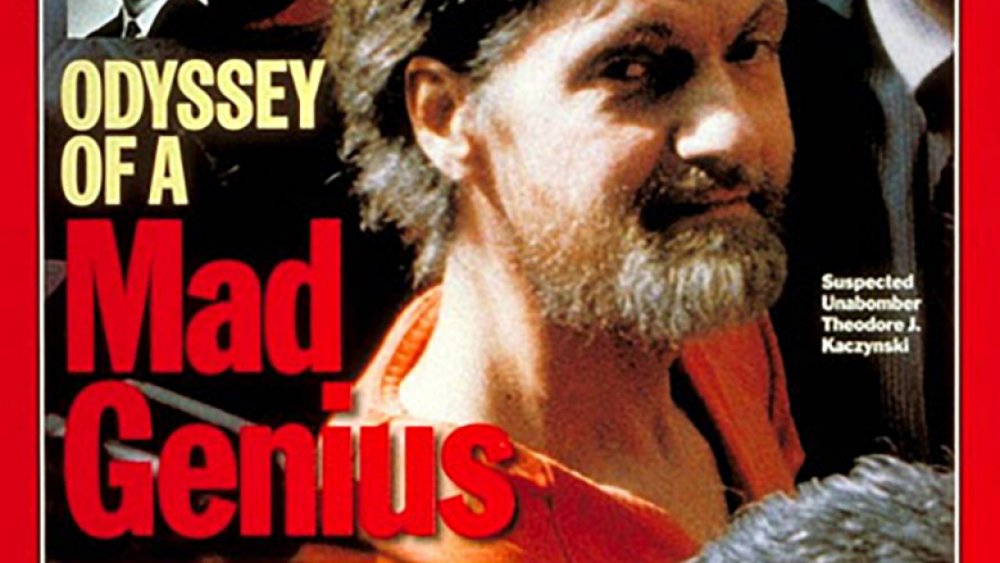

How Theodore John Kaczynski became the Unabomber and found himself on the FBI's "Most Wanted" list starts with some harsh truths, many of them concealed in his manifesto or revealed in the myriad writings about him. From genius to tortured soul, his life is a portrait of a serial killer in the making.

Ted Kaczynski was a brilliant child who struggled to fit in

To begin to understand the Unabomber is to start at the beginning. Theodore "Teddy" John Kaczynski was born May 22, 1942, in a Chicago suburb to Wanda and Theodore Sr., aka "Turk," who worked in a sausage factory and was an avid outdoorsman. The Kaczynskis were well-read, civic-minded, working-class people with liberal beliefs. The Catholics-turned-atheists were active in Democratic organizations and shared progressive views on politics and social issues, according to The New York Times. They insisted on education.

Wanda Kaczynski recalls her son as a happy baby until an isolating hospital stay. When he emerged, Teddy John was withdrawn and sullen, personality traits that would become defining characteristics.

Teddy was by all accounts a genius. An exact IQ is hard to verify, but nearly all place his within the 160-170 range. His smarts became a defining attribute for the young Kaczynski, who skipped two grades in elementary school. In 1958 (just having turned 16), he graduated high school as one of the state's five National Merit Scholar finalists. These academic successes proved isolating and would haunt him throughout his life. "Ted never acknowledged a greeting," a neighbor told the Los Angeles Times. "He just kept his head to the ground ... he was a loner."

Mischief started early for Ted Kaczynski

Years younger than his high school peers, Ted Kaczynski made attempts to fit in by joining the biology, German, coin, and math clubs, as well as playing trombone. But these weren't considered popular pursuits, and soon, Kaczynski's tendencies turned toward mischievous, childlike behavior in attempts to assimilate, according to the Los Angeles Times.

He and a group of boys had a "passion for devilish pranks, especially explosive ones," and they would sometimes produce harmless chemical reactions and smoke "bombs" in classes. One classmate recalled that Kaczynski's pranks escalated to showing someone how to make a mini-bomb. That device exploded in a chemistry class and blew out two windows. It also caused some temporary hearing loss in one girl. "Everyone was reprimanded, but Teddy was unfazed," according to The New York Times. "He later set off blasts that echoed across the neighborhood and sent garbage cans flying."

Another classmate recalled Kaczynski handing her a twisted piece of paper with chemicals in it. He asked her to unwind it, and when she did, according to the LA Times, it popped like a "little hand bomb."

Ted Kaczynski was a boy trying to be a Harvard man

At 16, Theodore Kaczynski entered Harvard on a scholarship, where he could have engaged with the brightest and the best, drawing on his genius to make connections. Instead, he chose isolation and resorted to displays of "odd" behavior. Kaczynski spent most of his time by himself in a cluttered, filthy, foul-smelling room in a shared suite and would occasionally blast loud, long notes from a trombone late at night. He would often rock in his chair, endlessly slamming it against the wall. A suite mate recalled him as "extremely reclusive," noting that "Ted stands out only for being completely without relationship to anyone in the suite."

Kaczynski excelled academically, obtaining a mathematics degree at age 20. He did not graduate with distinction or honors, nor did he spend any time participating in the traditional extracurriculars, according to The New York Times. After his arrest in 1996 and subsequent trial, the world would learn that Kaczynski took part in a psychological experiment while at Harvard. The experiment endeavored to test subjects' responses to stress through what is viewed today as an unethical and questionable methodology. It's likely — and largely — what shaped Kaczynski's future belief systems, according to The Atlantic.

Ted Kaczynski felt a need to disconnect from society

There is evidence that Ted Kaczynski's college years proved to be formative not just for his mathematical pursuits but also for his mental health and anti-technology, return-to-nature leanings. Kaczynski entered the University of Michigan in 1962 on a master's degree track. Again, he sought solitude as he did at Harvard, but his academics proved noteworthy and distinguished. He was diligent, thorough, and impressive when it came to his works. A professor told The New York Times that Kaczynski was "very persistent in his work. If a problem was hard, he worked harder. He was easily the top student, or one of the top."

Yet, while he immersed himself in his academics and ultimately completed his studies at Michigan, Kaczynski began to exhibit what some see as symptoms of mental illness and a desire to disconnect. A psychiatrist was appointed by the court to examine Kaczynski before his trial in 1998 on federal bombing charges, and based on interviews with him, she preliminarily diagnosed him as a paranoid schizophrenic and found that he "had fantasies of living a primitive life and fantasized himself as 'an agitator, rousing mobs to frenzies of revolutionary violence,' " according to The Atlantic. "He claims that during that time he started to think about breaking away from normal society."

And he did just that in 1969. Kaczynski abruptly left a tenure-track professor position at University of California Berkeley, ending a promising career in mathematics.

The Unabomber's plan for revenge emerged in the freedom of the woods

By 1971, Ted Kaczynski had turned part of his fantasy into reality and purchased about 1.4 acres of wooded property near Lincoln, Montana. On it, he built a wooden 10-by-12-foot rustic cabin. It had no running water save a well on the parcel and no electricity but a Coleman stove for cooking and a wooden stove for warmth.

The town assessed the property at about $4,000 and the cabin at $300. Annual taxes were $110. Kaczynski had no steady income — save for money from his parents and occasional odd jobs. He lived off the land, used a bicycle for local transport, and honed his survival skills ... all the while ruminating on the state of society and its turn away from nature.

One day, on a hike to find some "peace," he came across a sight that shook him — a road cut through the wilderness below a plateau near his cabin, Kaczynski said in an interview. "From that point on," Kaczynski said, "I decided that I would work on getting back at the system. Revenge." In May 1978, a bomb sent by mail detonated at Northwestern University, injuring a campus police officer. It was the Unabomber's first, but not his last.

The Unabomber maintained a revealing friendship with a stranger

Ted Kaczynski lived in the woods of Montana for 25 years, honing his bomb-making skills and becoming more angry and reclusive as the years passed. His primary — and sole — form of communication with the outside world, albeit limited, was through letters and correspondence with his parents and his younger brother, David Kaczynski. And he wrote to a Mexican man he never met ... perhaps the only sustained relationship the recluse maintained.

Beginning in 1988, Kaczynski corresponded with Juan Sanchez Arreola, sending the man about 50 letters, all written in formal Spanish and addressed to "my very dear and esteemed friend," according to The Baltimore Sun. David Kaczynski met and befriended Arreola, a farmhand, while living in Texas. It was he who suggested that Arreola correspond with Ted Kaczynski, who had studied Spanish.

The letters Kaczynski penned to Arreola spoke of his "reclusive life in a Montana cabin, his difficulties finding a job and hunting rabbit for food, his disappointment at not having a wife and children and his fascination with Pancho Villa, the Mexican revolutionary," according to The New York Times. Ted Kaczynski, whom Arreola called "Teodoro," even sent gifts for his pen pal's children ... a carved wooden cylinder painted with a Latin inscription "Mountain Men Are Always Free." The children used it as a pencil holder.

The correspondence from Kaczynski abruptly stopped a few months before federal authorities arrested him in April 1996 on suspicion of being the Unabomber.

Ted Kaczynski decided to cut off his family

By 1986, the Unabomber had mailed 11 bombs to targets at universities and airlines or with ties to academia. And in 1985, he claimed his first murder victim, a computer store owner in Sacramento. Meanwhile, Ted Kaczynksi's correspondence with his parents, Wanda and Ted Sr., became more accusatory and filled with vitriol, blaming his mother for not making him social enough and chastising his father for what he perceived as hurtful comments in childhood, according to The Washington Post.

In 1989, Ted Kaczynski lashed out when he learned that his brother David planned to marry. Though he'd never met David's fiancée, he nevertheless considered her "manipulative." Ted Kaczynski had started to cut off his family, asking them not to write anymore. At one point, he told his brother that he would only open a letter if the stamp was underlined ... an indication of some kind of family emergency. In 1991, when Ted Sr. was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, a letter arrived in Montana with an underlined stamp. Ted Sr. later committed suicide.

"Ted wrote back, and the response was fairly peculiar," David Kaczynski told The New York Times. "Basically, that I had done well, that this was something worth communicating."

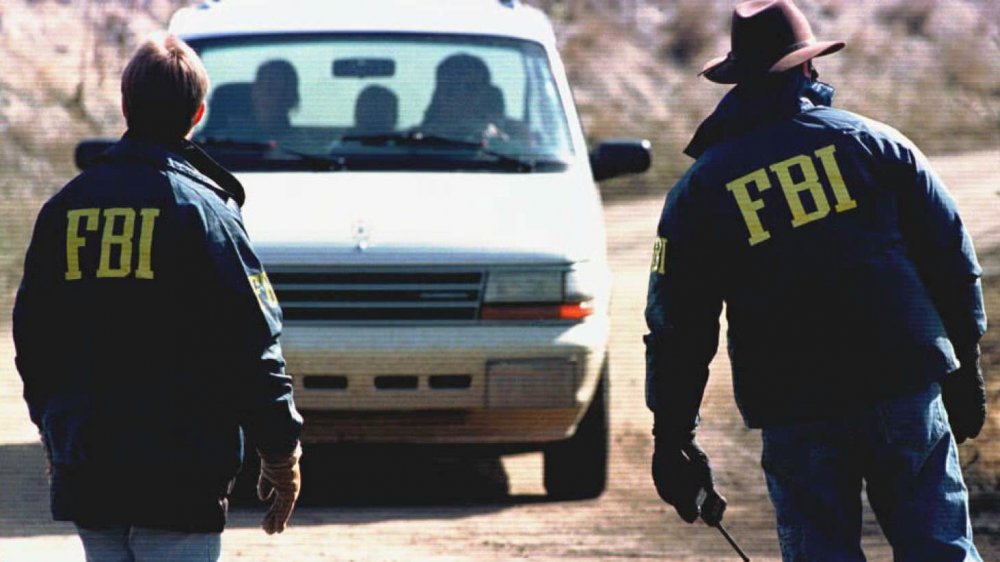

A task force gave Ted Kaczynski a name

The investigation into 16 bombings that killed three and injured 23 was the one of most expensive ($50 million) and longest in FBI history. That's largely because the Unabomber was a skilled mastermind, capable of eluding traditional detection methods. Over time, the bombs he built became "increasingly sophisticated." His method of delivery, hand-delivered or mailed, added to the mystery surrounding the nation's "most prolific bomber." A federal task force — more than 100 agents from the FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and US Postal Inspection Service — was established in 1979. The FBI called the case "UNABOM," which stood for "UNiversity and Airline BOMing" targets.

Several factors contributed to the Unabomber's ability to evade authorities, according to ABC News. He never left DNA or fibers on the devices, using gloves and a vacuum to clean up. The bombs were built with wood, not metal, making them hard to trace. And they were highly intricate, never detonating during delivery, only upon the recipient opening the package. "That's truly amazing in the eyes of the bomb-tech community," a former FBI agent told ABC News, calling the Unabomber "prolific."

Kaczynski was patient, too, going silent for months and even years on end. His targets were largely random, though all were connected in some way to academia, airlines, or technology. On top of it all, he lived completely off the grid. All this made him difficult to capture, and then, in 1995, the Unabomber's manifesto was published.

Ted Kaczynski as a published author

The Unabomber Manifesto, which appeared in The Washington Post and The New York Times and was titled Industrial Society and Its Future, was not the first time its author, Theodore John Kaczynski, had been published.

As a graduate student at the University of Michigan, he had published two papers on mathematics functions related to circles, creating some outstanding original research. Yet, it wasn't until they began to see Kaczynski's work being published in respected journals that his classmates or professors were even aware of this work, and they were simply amazed, according to The New York Times. "While most of us were just trying to learn how to arrange logical statements into coherent arguments, Ted was quietly solving open problems and creating new mathematics," a classmate told the Times.

When it came time for his doctoral dissertation, Kacyznski's failure to consult with professors derailed his original thesis, which had already been undertaken by a classmate. Fortunately, his two previously published works proved invaluable — he combined them into his dissertation "Boundary Functions." While brilliant, it lacked practical application, but it awarded Kaczynski his doctorate and earned the university's prize for best mathematical dissertation in 1967. His brother, David, said that Kaczynski didn't seem proud or gratified but rather seemed "more and more interested in the woods" — woods to which he retreated to write his most famous work ... the Unabomber Manifesto.

The Unabomber's own words ended his reign of terror

Ted Kaczynski preferred the written word to the spoken, sending countless letters throughout his life to family, strangers, and the one friend he cultivated while living as a hermit in Montana. His own words — not his DNA or a police sketch — would hold the key to his capture.

When the Unabomber's manifesto was published in 1995, it was regarded by some as the brilliant writing of a sane person. According to The Atlantic, one essayist called the Unabomber a "philosophical criminal of exceptional intelligence and humanitarian purpose, who is driven to commit murder out of an uncompromising idealism." While some saw the work calling for a revolution against technology as genius, David Kaczynski saw his brother in the 35,000-word treatise. Looking back at all those letters from Ted, David Kaczynski saw in the Unabomber's messages his brother's style and similar anti-technology sentiments.

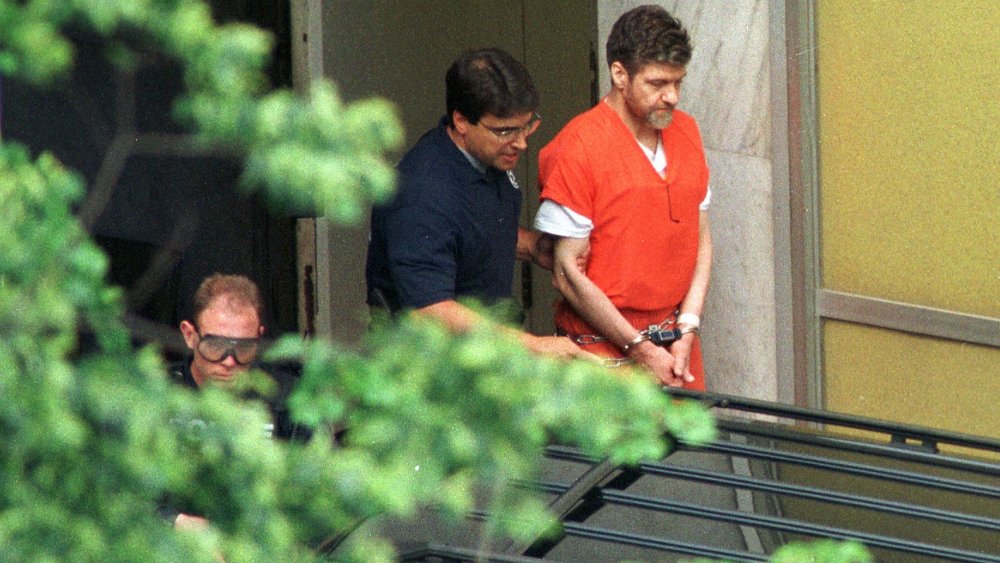

David Kaczynski contacted the FBI and gave them samples of his brother's missives, and the link was confirmed. On April 3, 1996, federal authorities knocked on the cabin door in Montana and arrested the Unabomber. Without the manifesto, one federal agent told ABC News, Ted Kaczynski "may still be out there in that cabin in the middle of nowhere in Montana."

The Unabomber forged relationships behind bars

The Unabomber's defense team sought to avoid the death penalty by using a mental illness defense, a move supported by David and Wanda Kaczynski and vehemently opposed by Ted Kaczynski. Insisting that he was sane, he ultimately pleaded guilty to federal charges in 1998 and was sentenced to life in prison. In June 2023, Kaczynski died by suicide while in federal prison. He was 81.

Human connections and relationships the Unabomber lacked as a free man, he forged and even fostered as a prisoner in a Colorado supermax prison. He even came close to marriage. Kaczynski was in Unit D, a section known during the late 1990s as "Bombers Row" because of its residents — Ramzi Yousef, mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, and Kaczynski. They would spend an hour together in the recreation yard in separate cages and would "just chat," according to The New York Times. For example, McVeigh and Kaczynski shared a common interest in survival skills.

Yahoo! News scoured Kaczynski's missives archived at the University of Michigan, and they discovered that the Unabomber fell in love behind bars. Joy Richards started as a pen pal and became Kaczynski's "Lady Love." The feeling was mutual, and the Unabomber wrote of marriage. In 2006, however, Richards died of cancer.

The harsh truth about the Unabomber's ideas

There has been renewed interest in the Unabomber in recent years, coinciding with milestone anniversaries of his capture and courtesy of "Manhunt: Unabomber" on Netflix. The revival has also spawned a subculture of Unabomber followers, who gather — quite ironically — online and identify themselves on social media using a pine tree emoji. "They spend hours sharing memes that call for the destruction of modern civilisation, and discuss fringe politics in Twitter group chats. This year they even sent Kaczynski a birthday card," according to Wired in 2018. "On the face of it, Kaczynski's new followers are angry, bored, and sick of the modern world."

Kaczynski's followers want to spark a dialogue about his ideas about technology and its effect on society, rather than talk about the Unabomber's crimes. It's not clear how impactful this group has been or what plans it may have in advancing those ideals. What does appear clear is that Ted Kaczynski, a reclusive criminal genius, may have been on to something. "It seems Ted being in prison has finally paid off," a pine tree follower told Wired. "He's gotten some extremely dedicated neo-luddites ready to contribute to the collapse of technological society."