The Legend Of The Mary Celeste Explained

There are few things creepier than ghost ships. How does an entire boatload of people just disappear in the middle of the ocean? The Mary Celeste is one of the most well-known examples of this phenomenon, and to this day, no one knows what happened.

If someone regales you with the tale of the Mary Celeste, the infamous ship found floating empty in the Atlantic in 1874, they will probably throw in some gruesome details — a bloody sword, a drunken crew, meals still sitting out half-eaten. And they will know the disappearance was down to a murderous passenger, or pirates, or a giant squid, or aliens. The Bermuda Triangle might get a mention, because why not?

The true story of the Mary Celeste gets lost behind the dramatic effects, but that doesn't make the central mystery any more bizarre: What the heck happened to the ten souls onboard? To this day, people are coming up with new theories, but will we ever know for sure? This is the legend of the Mary Celeste explained.

The Mary Celeste saw some early disasters

Once a ship is involved in a super-creepy event, of course people are going to side-eye everything else bad that happened to it. And sailing in the mid-1800s was far from a safe undertaking. Still, it does seem like the Mary Celeste had more than her fair share of bad luck long before its infamous voyage.

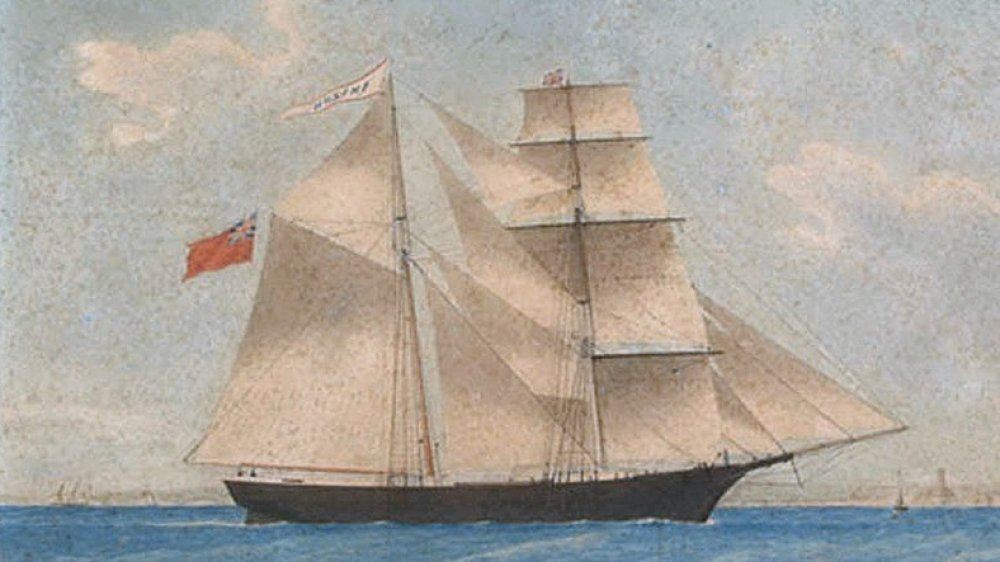

The Mary Celeste was built in Canada in 1861 and originally called the Amazon. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the problems started immediately. On the ship's maiden voyage, the captain came down with pneumonia and died. Under a new captain, the Amazon sailed to Europe, where she collided with another boat in the English Channel, which sank. Then things seem to have calmed down for a while. Ghost Ship: The Mysterious True Story of the Mary Celeste and Her Missing Crew records one crew member who worked on the Amazon for two years around this time as insisting later in life that there was "nothing unusual about the ship."

But by 1867, disaster was rearing its ugly head again. During a large gale, the ship was blown onto rocks off the east coast of Canada. The crew survived, but damage to the boat was so bad that the owners gave up hope of repairing her, or even getting her off the rocks. They sold the vessel to a local man, who immediately sold her again. This would become a pattern, as the ship was sold, seized by creditors, or auctioned many more times in quick succession.

The Mary Celeste was in good hands on her infamous voyage

By 1872, the ship had yet another new owner, a new captain, and a new name. The now-Mary Celeste was about to set off from New York Harbor, across the Atlantic to Italy. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, her cargo was 1,700 barrels of alcohol. Before you jump to the conclusion that the solution to the mystery involves those onboard getting drunk: It was denatured alcohol, which the appropriately named Professor Buzzkill explains is a solvent and will kill you straight-up if consumed.

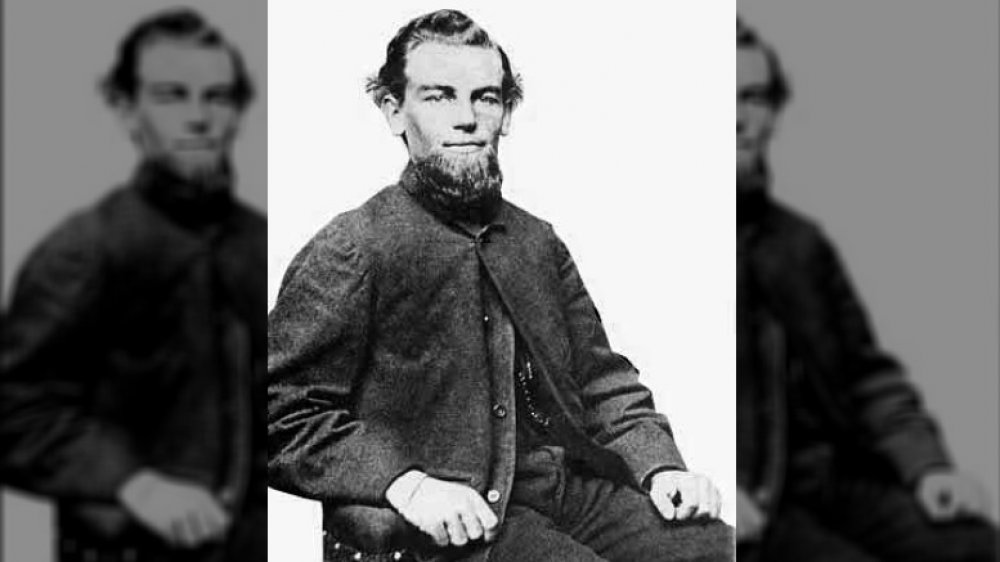

Captain Benjamin Briggs (pictured) was an experienced and "courageous" sailor, although this would be his first voyage on the Mary Celeste. Those who knew him said he was teetotal and read the Bible regularly. He was happily married with two young children. His wife and two-year-old daughter were also making the voyage, while his son stayed in America with relatives. There were seven other crew members, including First Mate Albert Richardson, who was considered good enough to have captained the ship himself.

Captain Briggs came from a seafaring family and had lost three siblings and an uncle to the ocean over the years. He knew the dangers of sailing, had an experienced crew, and was not the type of man who would "desert his ship except to save [lives]." Briggs prudently delayed starting off for two days when faced with bad weather. Finally, the Mary Celeste set sail, on what should have been a completely unremarkable trip.

The ghost ship is discovered

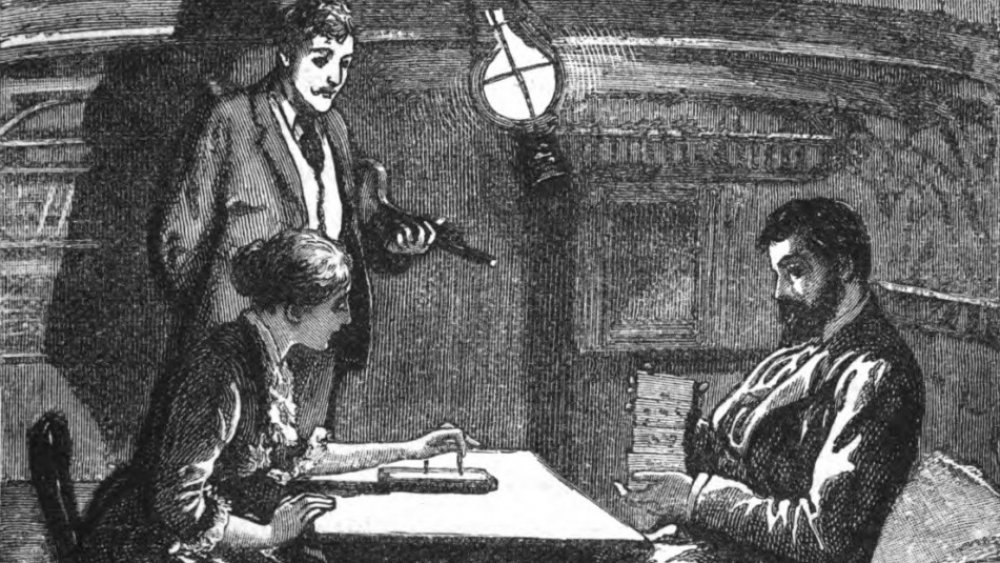

The ship Dei Gratia set off from New York in the same direction as the Mary Celeste a few days later. On December 5, 1872, the crew of the Dei Gratia spotted the Mary Celeste ahead of them in the east Atlantic. From the erratic way she moved, they could tell something was wrong. They hailed the ship, but when they got no reply, a couple of the crew members rowed over to see what was up.

According to Ghost Ship, what they found was a perfectly serviceable vessel ... with no one onboard. The lifeboat, chronometer, and sextant were missing, but everyone's personal belongings had been left behind, including their foul weather gear and some things of value. The hold was still full of the cargo of denatured alcohol. Although the logbook indicated that the Mary Celeste had hit the same bad weather all other ships in the Atlantic were also running into at that time, when the last entry was written on November 25, everything was fine.

The Dei Gratia crew members were perplexed. The hatches were removed, and the skylight was open. There was about 3.5 feet of water in the hold, but nothing that couldn't be pumped out easily. The slight damage to the rigging and sails almost certainly happened after the ship was abandoned. They determined the Mary Celeste was "apparently in good condition" and "nearly new." They couldn't figure out why, but it seemed like the occupants had left "in a great hurry."

The Attorney General was the first Mary Celeste conspiracy theorist

The Mary Celeste and her cargo were worth a lot of money, and the laws of the sea said "finders, keepers." Ghost Ship records that the Dei Gratia crew divided up and sailed both ships to Gibraltar. This was incredibly dangerous, since neither ship had enough men, but both made it safely, proving that the Mary Celeste was still perfectly seaworthy.

To claim salvage rights, the captain of the Dei Gratia had to go through the courts. What at first seemed like a simple matter quickly turned strange. From the beginning, the Attorney General thought there was "some sort of conspiracy." The crew testified that they found things on the Mary Celeste were wet and knocked over, but that was to be expected if she was unmanned at sea for a week. A few things were missing, but most of the items you'd expect on a ship were still there. One pump was out of order, but the other worked fine. There was no blood or signs of struggle.

This was too weird for the Attorney General, as it would be for many people who heard the tale. He believed either the crew of the Dei Gratia was working with those on the Mary Celeste in some sort of financial scam, or they had killed everyone onboard. But he couldn't prove it, so the judge gave the captain a salvage award, although much less than the ship and her contents were worth.

The cursed ship that went back to sea

In most tellings, the tale stops there. Empty ship, creepy situation, theories about what happened, the end. But that was far from the end for the Mary Celeste. Despite the fact that everyone onboard had seemingly vanished into thin air, the ship was still a useful, valuable piece of property.

According to Naked History, she eventually finished the voyage to Italy and then returned to New York the next year. By now, the vessel was infamous in the sailing community, and it took another year before anyone bought her. After that, the Mary Celeste had years of boring normality, sailing between Boston, the West Indies, and Africa, per Slate. But some bad luck still seemed attached to her: Captain Edgar Tuthill died during one voyage, and the ship continually lost money on her cargoes. The Mary Celeste appears to have been such a bad investment that people couldn't get rid of her fast enough: She had 17 owners in the next 13 years.

The Mary Celeste certainly hadn't been lucky for the captain of the Dei Gratia, David Morehouse, either. He was only awarded about one-fifth what the ship and cargo were worth, much less than would be expected in such a case normally. And the court made it clear they thought something fishy was going on, which put Morehouse under a cloud of suspicion for the rest of his career. It just didn't make sense that ten people would vanish from a perfectly good ship in the middle of the ocean.

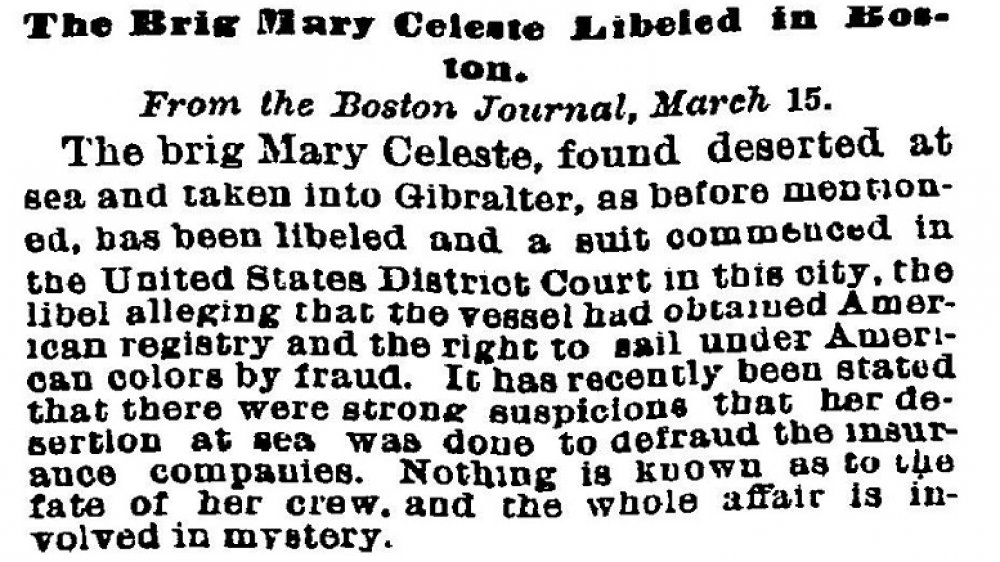

The big, fat Mary Celeste insurance scam

Most people are interested in the Mary Celeste because of the mystery surrounding the disappearance of her crew, but if indemnification is more your thing, then the ship is famous for a whole other reason. More than a decade after her infamous voyage, she was the central part of "one of the oldest cases of insurance fraud in U.S. courts."

In her later years, when the Mary Celeste inevitably lost her owners money, most of them just sold her. Not Captain Gilman Parker. He had a better, if much more illegal, idea. He loaded the Mary Celeste with virtually worthless cargo — cheap boots and cat food, according to The Telegraph, rotten fish and stale beer per other sources. Captain Parker took the Mary Celeste on one last voyage around Haiti ... and crashed her straight into a reef. It was a known reef, not one that would sneak up on an experienced captain.

The ship was ruined, but she didn't sink. Parker came back ashore, sold the wreck and its contents to a salvager, and then filed an insurance claim. Within months, he was in court, charged with fraud. The salvager said the cargo was not what he'd been promised, and the crew testified that the ship had been damaged on purpose. This was called "barratry" and was a death-penalty crime. The jury refused to convict because of the death sentence possibility, but Parker died within three months, anyway. It seems the Mary Celeste was bad luck to the last.

Things that definitely didn't happen to the Mary Celeste

So ... what the hell happened? Where did those ten people go and why? As one documentary on the Mary Celeste says (via Smithsonian) there are plenty of things we can rule out, from the seemingly reasonable to, you know, aliens.

Because people hear there was literally a boatload of alcohol, many assume the crew must have gotten drunk and mutinied. But had they imbibed the denatured alcohol, mutinying would have been impossible, what with the being dead and all. Plus, there was no sign of struggle, and stains that inspectors initially thought might be blood were proved to be something else, according to the New England Historical Society. If pirates were responsible, they were inept ones, since the cargo was undisturbed, and other valuables were found onboard. And while the crew of the Dei Gratia was under suspicion, they had no motive.

As for the more out-there theories: Obviously, it must somehow be the Bermuda Triangle's fault, even though the Mary Celeste was thousands of miles away from it. As for a giant squid attack, while they have been known to grab onto boats very rarely, it would take an extremely special animal to pick off almost a dozen people and drag them into the deep. And some have claimed the Mary Celeste's occupants robbed another ship of treasure and then started new lives in Spain ... which would mean that the captain and his wife just abandoned their young son, whom they'd left in America.

The too much bad luck theory

There are plenty of ridiculous or unlikely theories we can rule out, but there are a few that are more reasonable. The documentarian Anne MacGregor looked into the case in 2007 (via Smithsonian). She found there was no evidence in his past that Captain Briggs would do anything irrational or hasty. He had always been steady and sober and was experienced. Plus, his wife and child were onboard. So whatever the reason he gave to abandon ship, it must have been rational and seemed necessary.

MacGregor meticulously looked over all the evidence and came to the conclusion that, basically, a whole bunch of smaller things went wrong, which made it look like something big was going wrong. The Mary Celeste had been used to transport coal on her previous voyage. One of the two pumps which was used to remove water from the hold had broken, probably because of a buildup of coal dust. The hold was so packed with barrels that it was impossible to check the water level. And rough seas meant the Mary Celeste could be taking on dangerous amounts of water.

Based on notes in the ship's log, it appears the Mary Celeste's chronometer (the instrument that lets sailors know their location based on longitude) was faulty, and Briggs would have been slightly lost. So when he finally saw land (the Azores), and having no way of knowing if the ship might sink, Briggs ordered everyone to the lifeboat. Then ... they didn't make it, for some reason.

The alcohol fume theory

Another possible theory does involve the alcohol the ship was transporting, but not in a drunk mutiny way. The author of Ghost Ship: The Mysterious True Story of the Mary Celeste and Her Missing Crew told AccuWeather about his hypothesis in 2020.

The denatured alcohol in the hold was essentially an industrial chemical. When the ship was discovered, nine of the barrels in the hold were empty. All of them were made of red oak, which was more porous and likely to leak than all the other barrels, which were white oak. 450 gallons of methanol pouring into the hold would cause a serious fume problem. Since the weather had been bad, the hold had been closed up for weeks. So when the weather improved, Briggs could have ordered "every hatch, door and window" opened (which is how they were found), attached the lifeboat to the ship with a rope, and ordered everyone in while the dangerous fumes dissipated. This would also explain why important documents and valuables were left behind, since those in the lifeboat thought they were coming right back. Then the weather must have changed, a strong wind caused the towline connecting the ship and lifeboat to break, and all those in it were doomed.

A variation on this theory is that the fumes ignited, causing a huge bang. An experiment in 2006 found this was possible without leaving any scorch marks. Thinking the ship was about to explode, Briggs gave the order to abandon ship.

The discovery of the Mary Celeste ... or not

It seems that even on the bottom of the ocean, the Mary Celeste is still able to screw with people. In 2001, author and marine archaeologist Clive Cussler (pictured) announced he'd found the remains of the infamous ship off Haiti. Cussler might be known for writing popular fiction, but he has serious credentials in the historic shipwreck discovery field as well, leading expeditions that found almost 70 by 2001, including some that were extremely notable. So there was no reason to doubt he'd done it again, with the most famous ship to date.

The BBC reported the wreck was "almost completely covered by coral," which made finding it especially difficult. But Cussler and his team did it and proudly showed off artifacts from the ship recovered by their divers.

But by 2005, the history of the Mary Celeste had to be rewritten yet again. According to The Independent, Cussler's expedition had retrieved timber from the wreck, and when it was analyzed by the Geological Survey of Canada and the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona, they found there was no way this was the Mary Celeste. As one researcher explained, "The outermost ring suggests the timber was from trees still growing in 1894, but the Mary Celeste sank 10 years before that." Furthermore, the type of wood was all wrong, and not native to the places the ship was built or refitted. So, yet another mystery still to solve.

Why do we get so much wrong about the Mary Celeste?

Abandoned ships were uncommon but not unheard-of in the 1800s. That is, after all, why there was a legal procedure when Captain Morehouse salvaged the Mary Celeste: because the situation was a relatively normal occurrence. Most of the details of these empty ships have been lost to history, and the story of the Mary Celeste might have been forgotten, too, if not for one significant difference.

According to Smithsonian, a young, pre-Sherlock Holmes Arthur Conan Doyle heard the story of the Mary Celeste and used the barest facts about it to write a short story called "J. Habakuk Jephson's Statement." It was published in the prestigious Cornhill Magazine and was a sensation. It was complete fiction but was written in a way that made it seem like a true account by the lone survivor of the voyage of the "Marie Celeste." The titular survivor explains that a vengeful ex-slave on the ship systematically murdered all the passengers, and he himself barely escaped.

Plenty of those who read the tale, including the Attorney General who had tried the original salvage case, thought it might be true. Many of the details in the story ended up mixing with the actual facts, until what most people think they know about the mystery today is a combination of the real and the totally made-up. More tellings, like a 1935 film starring Bela Lugosi, muddled things further. But the real story is weird enough, without later embellishments.