The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Ella Fitzgerald

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The First Lady of Song, the Queen of Jazz, Lady Ella — whatever you call jazz, swing, and bebop legend Ella Fitzgerald, it can hardly encapsulate the incomparable pitch, melodic sophistication, expert diction, and crystalline clarity of her voice. Fitzgerald enlivened mid-20th century pop music with her popular songbooks featuring the compositions of Cole Porter, Duke Ellington, and Ira and George Gershwin, among others. Admired by her peers, she worked with jazz greats like Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole, and Frank Sinatra. "I never knew how good our songs were," Ira Gershwin once said, as quoted by The New York Times, "until I heard Ella Fitzgerald sing them."

Selling over 40 million albums in her lifetime, Ella Fitzgerald gained a devout audience across race, gender, and class lines for over six decades. What's often left out of her legacy as a celebrated jazz singer, however, is her troubled childhood, years on the street, and the painful pushback she got from forging beyond racial barriers. This is the tragic real-life story of Ella Fitzgerald, who quietly rose from the humble streets of New York to become the beloved American icon with the glass-shattering voice.

Ella Fitzgerald's tragic beginnings

Ella Fitzgerald was born in Newport News, Virginia, on April 25, 1917, to her mother, Temperance Fitzgerald. Her father left the picture when Ella was two and a half, and she never developed any relationship with him. Like many families during the great migration, Temperance struggled to make ends meet and moved north to Yonkers, New York, with her daughter and new boyfriend Joseph Da Silva. There, young Ella thrived in school, taking an interest in the church choir and dance and falling in love with the jazz records her mother brought home.

As a girl, Ella was meek but still incredibly ambitious. Neighbor Annette Miller recalled how she would tell the local kids, "Someday you're going to see me in the headlines. I'm going to be famous," as told in Stuart Nicholson's biography Ella Fitzgerald: A Biography of the First Lady of Jazz. She learned to imitate her favorite singers on the radio and phonograph and would take trips to the city to check out the latest steps at dance halls.

That determined young girl would be waylaid by grief. Tragically, in 1932, Temperance died in a car accident, leaving 15-year-old Ella an orphan during the height of the Great Depression. After Temperance's passing, it's alleged that Ella's stepfather mistreated her. By 1933, she'd fled to her aunt's in Harlem to escape. However, as reported by NPR, Ella's aunt struggled to support her.

Ella Fitzgerald becomes a ward of the state

After she moved to Harlem, Ella Fitzgerald entered a dark period — one she almost never spoke of publicly. She skipped school, and she took up work as a lookout at a bordello and as a courier for a numbers-runner. With her truancy and ties with criminal work, Fitzgerald was sent to the overcrowded Colored Orphan Asylum in Riverdale, according to The New York Times.

After that, she was moved to the New York Training School for Girls, a state reformatory school in Albany notorious for its squalid conditions. In fact, Fitzgerald was said to have been held in the basement of one of the cottages, where she was allegedly beaten and served only bread and water. When she tried to join the school choir, she was banned due to her race. Fitzgerald, underage in a discriminatory world, was powerless in the legal system. Running away from the reformatory school, she lived hand-to-mouth and danced for tips on 125th Street in New York. According to PBS American Masters, Fitzgerald slept wherever she could, essentially homeless.

Ella Fitzgerald might have concealed her troubled years from the public, but they were deeply etched into her psyche. When the New York Training School for Girls invited her to come back as a "success story" in the 1960s, she refused them.

Ella Fitzgerald gets paroled to a big band

Ella Fitzgerald's big break came at age 17, when she put her name in to perform at the Amateur Talent Night at the Apollo Theater in 1934. Fitzgerald had planned to dance, but after watching the reigning dance duo the Edwards Sisters, she decided to sing. As she inched onstage, according to Fitzgerald in the documentary "Ella Fitzgerald — Something to Live For," someone in the famously tough crowd hollered, "What's she going to do?"

What she was going to do was stun the crowd. Fitzgerald wowed them with renditions of "The Object of My Affection" and "Judy," imitating her favorite singer Connee Boswell, and won first place. From that exposure, Fitzgerald met bandleader Chick Webb, who was looking for an accompanying female singer for Charlie Linton. After a few trial gigs, Webb asked her to join the band for $12.50 a week. Still a ward of the state, Ella Fitzgerald was paroled to Chick Webb's band, as noted by History.

By 1938, Fitzgerald had brought the big band acclaim when she helped co-write the nursery theme "A-Tisket, A-Tasket." Sadly, Chick Webb died of tuberculosis in 1939, and Fitzgerald lost her friend and father figure. It was her turn to take the lead at just 22. Renamed Ella and Her Famous Orchestra, the group went on to record 150 songs before disbanding in 1941, per the National World War II Museum New Orleans.

Ella Fitzgerald was harshly judged for her looks

Despite her undeniable talent, both Fletcher Henderson and Chick Webb were initially hesitant to hire Ella Fitzgerald, with her unkempt hair, eyeglasses, and modest clothing. When Chick Webb first saw her, he whispered to Charles Linton, "You're not puttin' that on my bandstand," according to the Houston Symphony. Going from living on the streets to working ballrooms within months was quite a transition. As reported in Geoffrey Mark's biography Ella, Chick Webb's band members had to teach her grooming and hygiene, as her years without parents had left her naive about the beauty paradigms of the 1930s.

But the unflappable Ella Fitzgerald took her bandmates' jabs about her shoes, dresses, and hair in stride. "I used to wish I was pretty," Fitzgerald recalled, per the book Words of Wisdom. "My cousin Georgia always taught me that if you smile, people will like you." Fitzgerald proved that talent and verve transcended first impressions. As The New York Times put it, "Ella Fitzgerald fit no available or desirable cultural type... [People] didn't want to be her or have her. And so she turned herself into a force of music." With peerless diction and a girlish tone, Fitzgerald had a breakthrough hit by 1938 and brought the melodic ease of scatting and swing to an audience reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, and soon, the coming war.

Ella Fitzgerald endures the USO's hypocrisy

By 1940, Ella Fitzgerald enjoyed popularity at home and a spark of fame abroad. Her singular voice proved to be a salve for men and women enduring the fallout of World War II. In fact, hundreds of copies of "The Muffin Man" were sent to London to boost morale during the Blitz, according to the National World War II Museum New Orleans. Like her peers, Fitzgerald volunteered her talents with the United Service Organizations (USO), bringing her musical stylings to troops.

Though Fitzgerald was providing a service, she still — like her contemporary African American performers — experienced heinous racial discrimination during her time volunteering. Despite championing equality in their policies, many USO shows were segregated: Of 3,000 total USO clubs, only 109 staffed by white volunteers would admit African Americans. Fitzgerald was restricted to certain cars on public transportation and had limited hotel options. It's reported that on a crowded train near the DC area, Fitzgerald took a seat on a whites-only car after she was unable to find other seating. While the conductor forced her off, a group of white sailors insisted that she remain with them.

Tour legs were full of these humiliating discriminations, inconvenient accommodations, and separate venues, but Ella Fitzgerald, magnanimous as ever, still packed her schedule. Despite the hypocrisy, at the age of 24, she was billed as a "special attraction" at USO benefit shows.

Ella Fitzgerald finds an advocate in Norman Granz

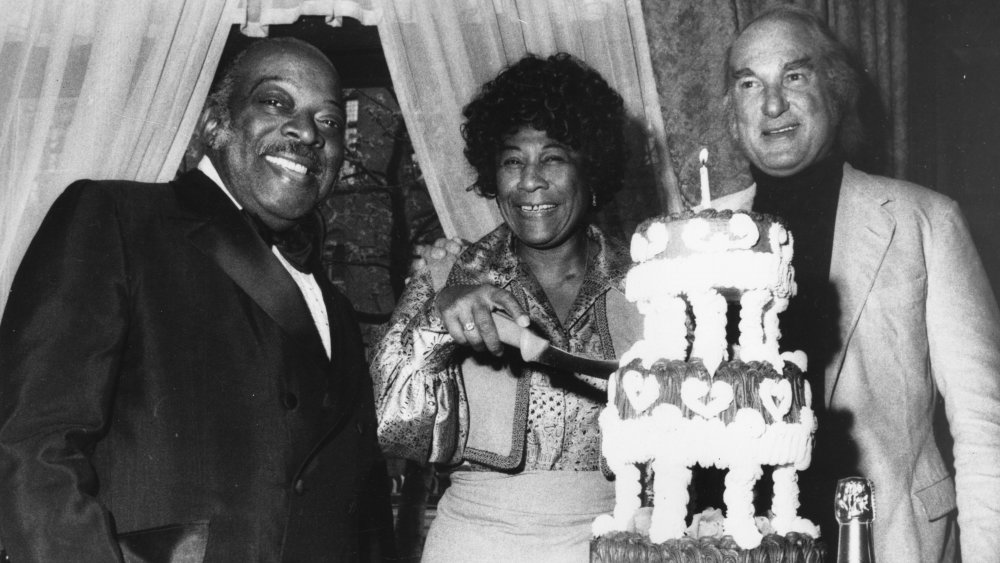

Ella Fitzgerald struggled to progress her sound beyond bebop. Her catalog, which, by the late 1940s, consisted of standouts like "Flying Home" and "Lady Be Good," was full of fluffy novelty tunes that were considered below her skill level by critics. Enter the game-changing Norman Granz, who invited her to join the Jazz at the Philharmonic series in 1949. Granz became her manager, signing her to his label Verve when her contract with Decca Records lapsed.

As noted by The New York Times, it was Granz who first suggested that Fitzgerald record songbooks of major composers, a career-defining pivot. With the Cole Porter Songbook and the Rodgers & Hart Songbook, she was exposed to the public as more than a jazz or scat singer. She would become an interpreter of great composers and expand her work to major concert venues like Carnegie Hall and take bit parts in films like Pete Kelly's Blues and St. Louis Blues.

Norman Granz was not solely a champion of artistic progressiveness, but he also lobbied for top and equal treatment for his signed performers, per NPR. Granz wrote it into the contracts of his artists that they wouldn't play segregated halls. Fitzgerald would later say that meeting Norman Granz, who became her advocate and business partner through the 1970s, "was a turning point in my life."

Ella Fitzgerald gets a boost from Marilyn Monroe

Despite her immense popularity from novelty songs and singles from the 1940s, Ella Fitzgerald's race and plain appearance kept her relegated to small jazz clubs and far from major nightclubs. However, that all changed in 1954, when actress Marilyn Monroe, at the peak of her Gentlemen Prefer Blondes fame, saw Fitzgerald perform, and the two became fast friends. The following year, when the nightclub Mocambo in West Hollywood refused to book Fitzgerald because of her weight and looks, Monroe leveraged her star power. Per Biography, Monroe cut a deal with Mocambo's owner that she — along with her celebrity friends — would sit in the front of the club if, in exchange, he gave Fitzgerald a try. Who could resist Marilyn Monroe?

In March 1955, Fitzgerald headlined the Mocambo for a few weeks, selling the house out and bringing in stars like Frank Sinatra and Judy Garland. A few more times over the course of their friendship, Monroe stepped in to boost Fitzgerald's signal and advocate for the respect she deserved. Due to her race, Fitzgerald was sometimes asked to enter a club from the side door — but not anymore. As quoted in Marilyn Monroe: Cover to Cover, Fitzgerald told Ms. Magazine in 1972 that, "I owe Marilyn Monroe a real debt."

This was a turning point in Ella Fitzgerald's touring. In fact, the profound impact of the pair's compassionate friendship inspired the 2008 play Marilyn and Ella.

Ella Fitzgerald's failed marriages

In 1941, after Chick Webb's death, Ella Fitzgerald married Benjamin Kornegay, a shipyard worker known for petty theft and drug-dealing. Encouraged by bandmates and handlers to end the marriage, Fitzgerald got an annulment a year later. Reportedly, as told to BBC Four Legends, the judge at her annulment told her, "You just keep singing 'A-Tisket, A-Tasket.' "

At age 30, Fitzgerald married bassist Ray Brown. It was a love affair of musicians with the same passion — it was also a love affair of conflicting schedules. The pair adopted the son of Fitzgerald's half-sister and named him Ray Jr., but their son was frequently in the care of Fitzgerald's aunt Virginia due to touring. Brown and Fitzgerald divorced in 1953, leaving Ella devastated, as reported by The New York Times. Meanwhile, Ray Jr. and his mother were distanced. Fitzgerald admitted that her son largely had to raise himself because she was always on tour.

Healing from her divorce, it was rumored that Fitzgerald had a secret marriage with Norwegian producer Thor Einar Larsen in 1957, per The Independent. The romance was cut short when Larsen was arrested for stealing money from a former fiancée and barred from entering the US. Yet again, Fitzgerald was taken in by a man with a criminal past. Never one to openly complain, she funneled all that grief into her tunes.

Fame in the time of segregation

Championed today as a civil rights pioneer, Ella Fitzgerald experienced plenty of discrimination in her career. "I worked with the band when we had to travel through the South, and I went through all those experiences," Fitzgerald said of her early career in Ella Fitzgerald — Something to Live For. "I feel grateful that I've been able to pay all those dues... that's how we become greater."

In 1955, Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, and a few members of their bands were arrested in Jim Crow-era Houston for playing dice in their dressing rooms backstage. It was an overtly racist sting — Fitzgerald recalled to the Los Angeles Times, "At the police station, they even had the nerve to ask me for my autograph."

Sometimes, she fought back. In 1954, Fitzgerald and her entourage were bumped from a Pan American flight, for which she had a first-class ticket, on the way to the Australian leg of her tour, as reported by The New York Times. Stuck in Honolulu and unable to reboard to retrieve their belongings, Fitzgerald was forced to cancel her first two tour dates. She filed a lawsuit for $270,000, citing humiliation and pain from racial discrimination, according to the court record. When interviewed by CBC about the incident, Fitzgerald said she got "a nice settlement" and, in the face of discrimination, wouldn't hesitate to sue again.

Ella Fitzgerald was incredibly shy

Ironically for such a charismatic performer, Ella Fitzgerald was cripplingly self-conscious and shy. Rarely giving interviews, the First Lady of Song only ever felt at home when she was onstage. "I don't want to say the wrong thing, which I always do. I think I do better when I sing," she was quoted as saying by CNN.

A focal point of Fitzgerald's anxiety was her weight. "I always try to think 'I'm going to be happy.' I look at myself and say, 'Now, Ella, you could lose that weight and be just like so-and-so.' Then I'll get real self-conscious," she said in Ella Fitzgerald – Something to Live For. Singer Charles Linton recalled, in Stuart Nicholson's Ella Fitzgerald: A Biography of the First Lady of Jazz, how when Fitzgerald saw people staring at her, she assumed it was about her appearance, not the more likely reason that they were huge fans.

That lack of ego persisted even as Fitzgerald's fame skyrocketed through the decades. According to the Los Angeles Times, she was shaking in her boots to perform with Bing Crosby in the 1940s, and when she met Clint Eastwood, she ended up asking him for an autograph. Bandmates reported that she always went straight home from live shows. It was hard for Ella Fitzgerald to keep a social life outside of her grueling 45-weeks-per-year touring schedule.

Ella Fitzgerald suffered from progressive illness

In many ways, Ella Fitzgerald regarded her role as the Queen of Jazz more seriously than her own heath. With a neck-breaking tour schedule, Fitzgerald began to feel the wear on her body after three decades on the road. In the early 1970s, she had an eye cataract removed and also suffered an eye hemorrhage, as reported by the Los Angeles Times. Fitzgerald was in and out of hospitals for respiratory illnesses or exhaustion.

In 1986, she underwent quintuple bypass surgery and rested for a scant nine months before booking performances again. She played at least once a month through the early 1990s, according to The New York Times. One of the motivators for remaining active through decades of weakening health was that Fitzgerald was addicted to singing and got bored at home. The other reason was that she simply needed the money, noted her friend Phoebe Jacobs in a BBC Four Legends special. When her half-sister passed away, Fitzgerald saw to supporting her extended family financially, and that required even more dates.

In 1993, tragically, Fitzgerald's legs were amputated below the knees due to complications from diabetes, and her touring stopped, as told by Encyclopedia Britannica. At age 79 in 1996, she passed away from a stroke.

Ella Fitzgerald's lost legacy

Ella Fitzgerald had an incredible 60-year career that won her 14 Grammys, sold over 40 million records, earned her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and got her the National Medal of Arts. Tragically, in 2019, it was revealed that Ella Fitzgerald's catalog was among the loss of material in the 2008 Universal fire, as the The New York Times reported. This means Fitzgerald's estate will be unable to reissue or remaster a large portion of her work in the future.

However, the delightful jazz, pop, and swing Fitzgerald delivered to the world was not her sole legacy. Throughout her life, she was intent on bolstering the lives of orphaned children, including funding housing for a war orphan in Naples post-World War II, according to the National World War II Museum of New Orleans. Knowing that it was a dose of luck and talent that had uplifted her from poverty, Fitzgerald sought to enrich the lives of all disadvantaged children. She founded the Ella Fitzgerald Charitable Foundation in 1993, which aimed to provide assistance for at-risk youth and develop art programs.

Though Ella Fitzgerald became one of the most successful and highly decorated vocal performers of a generation, her small beginnings remained a motivation for her work. With her soft-spoken humility and endless dedication to her craft, Lady Ella never stopped trying to earn the love of her audience.