The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath remains a singular voice in American literature nearly six decades since her death. A rising literary star during a point in American history when women were beginning to agitate for equal rights and a life outside of traditional gender roles, her poetry combined brutal and sometimes vulgar imagery and language with an honest depiction of depression and mental illness that was startling and bracing — and inspiring to many generations since. In her poems and her autobiographical novel The Bell Jar, Plath explored her own unhappiness, her relationship with her family, and her marriage to writer Ted Hughes, whom she married after just four months and who was brazenly unfaithful to her.

What readers find when they discover Plath's work is a woman who was clinically depressed, who heroically battled that depression her whole life, and who found the final betrayal by the man she loved to be too much to bear. The sadness and anger that imbue Plath's writing inspired some of the most powerful verse of the mid-20th century, and the words that stemmed from the tragic real-life story of Sylvia Plath continue to resonate with readers today.

Sylvia Plath's story is a tragedy. If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Sylvia Plath never got over her father's death

Sylvia Plath's father, Otto, became ill with diabetes when she was just four years old. After years of struggle and the amputation of one leg, Otto passed away when she was eight. His death was not just an economic blow to the family, which was plunged into near-poverty, but an emotional one for young Sylvia. Otto was by all accounts a cold, unhappy man – The Guardian reports that the FBI file on Otto (compiled during World War I when Plath emigrated to the US but showed little love for his adopted country) concluded he was "a man who makes no friends."

Otto's shadow loomed large over Sylvia for the rest of her life. One of her most famous poems, written in 1962 not long before her death, is "Daddy," which contains the lines "Daddy, I have had to kill you/You died before I had time" and uses Holocaust imagery to describe her feelings of anger and resentment toward her father, ultimately describing her painful sense of freedom from his legacy. Yet careful analysis indicates this wasn't successful — as author Jon Rosenblatt notes, despite her attempts in the poem to underscore her triumph over her father, he keeps returning in different forms throughout the piece. Plath struggled with her relationship with her father right up until her final days.

Sylvia Plath wanted to be an artist

It might be hard to believe when discussing a writer of Sylvia Plath's caliber, someone whose work not only continues to be taught and studied but which earned her a posthumous Pulitzer Prize, but Plath initially considered herself an artist and wanted to pursue an art major when she attended Smith College. In fact, one of her early works, Triple-Face Portrait, was singled out by National Portrait Gallery curator Dorothy Moss for its use of color and cubist technique despite the fact that Plath painted it while still in high school. But as Vice reports, her teachers recognized something special in her writing and pressured her to change her major to English.

The tragedy of this is that Plath loved making art so much that she never stopped. She sketched, painted, and made collages throughout her life but never made any attempt to have her work exhibited or to seriously pursue that aspect of her creativity. Her artwork ranges from the whimsical and hilarious to dark glimpses of her unsettled mind, and Plath was known to spend a lot of her time in museums and galleries, taking comfort and inspiration from great works of art. We can only speculate what might have happened if she'd been able to pursue her art to a fuller extent.

Sylvia Plath never got over her first love

Plath's relationship with Ted Hughes initially seemed like a fairy tale: Two immensely talented writers met at a party in Cambridge and were married almost immediately. Plath and Hughes both wrote about their initial meeting, and it was clearly a seismic event for both. (Plath described Hughes as "That big, dark, hunky boy, the only one there huge enough for me.") But it wasn't a simple case of love at first sight for Plath, because she was still pining for her first love — someone she never quite got over.

As The Stranger reports, Plath's private journals reveal that even after spending a night with Hughes shortly after their first meeting, she ran off to Paris to meet a man named Richard Sassoon, a Frenchman she'd met while still attending Smith College — but Sassoon never showed up for their meeting. She searched desperately for Sassoon in the age before cell phones but couldn't find him — and so returned to England, where she married Hughes a few months later. Author Andrew Wilson believes that if Sassoon had kept their appointment, Plath would have married him instead — changing the course of their lives forever. In Plath's case, that might have meant a life that extended years or decades more.

Sylvia Plath's big break broke her

Sylvia Plath was a bona-fide genius, testing high on IQ tests and skipping grades in school. (In fact, she was held back once simply to keep her with children her own age.) She was already making a name for herself while in college, and in 1953, she was offered a plum prize: a guest editorship with Mademoiselle magazine in New York City.

It should have been the beginning of a glamorous, exciting time for Plath. It should have cemented her as the "It" girl of 20th-century letters — young, beautiful, and incredibly talented. Tragically, Plath's experience was the opposite, and much of her time in New York that summer made its way into her novel The Bell Jar in fictionalized form.

Plath didn't like New York. The heat, the fakeness of the upper-crust fashion world she found herself embedded in, and the beggars and garbage that plagued the city at the time all made her depressed. But as The Guardian reports, the real reason Plath fled New York may have been an attempted assault. She met a man named José Antonio La Vias (whom she later described as "cruel" without elaboration) and went to his apartment at least once. When she returned from New York shortly thereafter, her family found her changed — somber and quiet. Notably, The Bell Jar has a scene where protagonist Esther is attacked by a man named Marco, who bears a strong resemblance to La Vias.

Sylvia Plath's husband abused her

The amount of blame Ted Hughes deserves for Sylvia Plath's early death is a matter of debate, but there is little doubt that he was not a good husband to her. Hughes, who is regarded in his native Britain as one of the greatest of their modern poets, cheated on Plath a lot and was actually with one of his lovers when Plath died. And much of Plath's unhappiness during the last years of her life focused on her husband, a hard-drinking and unfaithful man.

But according to The Guardian, it wasn't until some of Plath's final letters were published in 2017 that the world found out just how bad a husband Ted Hughes was. In the letters, Plath accuses Hughes of beating her on several occasions — including shortly before she suffered a miscarriage in 1961. These letters were sent to her former therapist, Dr. Ruth Barnhouse, and might explain why Ted Hughes claimed that Plath's journals and letters had been lost or destroyed after he gained control of her literary estate in the wake of her death. For years, many have speculated that Hughes destroyed these writings (including a legendary, supposedly brilliant second novel) to protect his own reputation, and these new letters bear out that theory.

Sylvia Plath's career was wrought with rejection

Sylvia Plath is a fixture of modern literature today, with her poems and novel studied and the often devastating details of her life and fight with depression the subject of biographies and films. With her early success and fame during her college years and a posthumous Pulitzer Prize, it's easy to imagine that Plath was a publishing juggernaut during her life.

In fact, publishing her material was often a challenge, and Plath's professional career was actually marred by a great deal of often savage rejection. As Salon notes, even some of her most famous poems like "Daddy" and "Lady Lazarus" were rejected by poetry journals for being "too extreme" for the staid 1950s and 1960s. Plath often ran into this attitude — her poetry frequently used violent imagery and vulgar language which only appears modestly shocking today but was very controversial at the time.

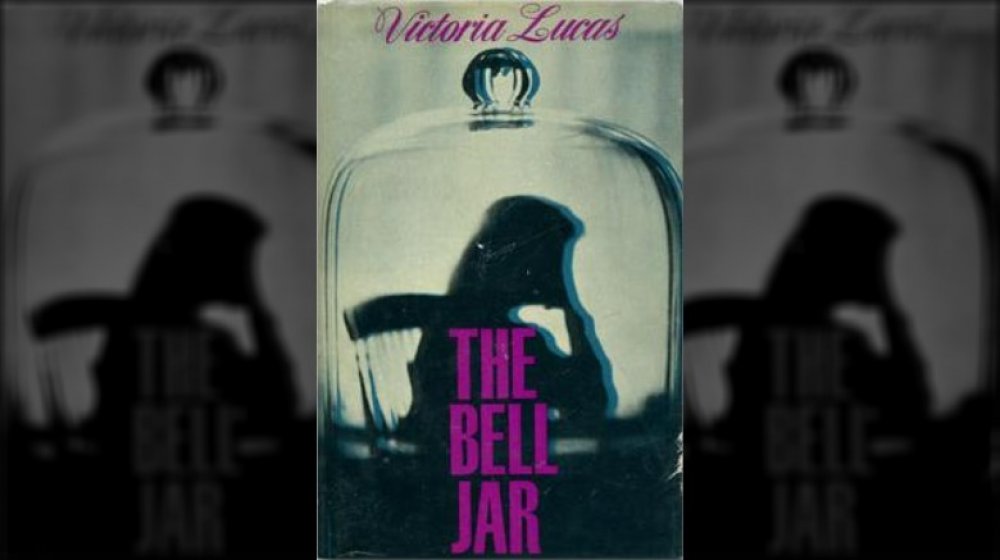

But the worst experience of rejection came with her novel The Bell Jar. Not only was this book — today recognized as a classic — rejected by Harper & Row, her publisher, but they called it "disappointing, juvenile and overwrought." Adding insult to injury, Harper & Row had paid for the writing fellowship that allowed Plath to work on the novel, so in a sense, they were rejecting a book they'd already paid for.

Reviews of The Bell Jar weren't good at first

Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar is a painfully personal novel. In fact, it's transparently autobiographical once you know that Plath is the author. But when the novel first published, no one knew Plath had written it, because she published it under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas since she was worried about offending some of the people who served as inspiration for some of her characters. As Saul Maloff wrote in The New Republic, "Only the names were changed, nothing else: as much as a novel can be, it was recorded rather than imagined."

As Salon notes, however, for years after its publication, the reviews of the novel were not very positive. Typical of the early reception the novel received is The New Republic's 1971 review, calling the book "no firebrand" and a "slight, charming, sometimes funny and mildly witty, at moments tolerably harrowing 'first' novel, just the sort of clever book a Smith summa cum laude (which she was) might have written if she weren't given to literary airs."

Over the years, Plath's reputation grew — and with it, the reputation of her only novel. Today The Bell Jar is recognized as an incredible work of psychological honesty, an exploration of depression in the modern age and the pressure of gender roles and expectations. Sadly, Plath herself went to her grave thinking no one understood her most personal work.

Sylvia Plath was troubled and suicidal

The one thing most people know about Sylvia Plath is that she committed suicide at the age of 30, cutting short a brilliant literary career and leaving behind two young children. The true tragedy of Plath is that she worked very hard to present the appearance of calm and happiness but spent almost the entirety of her life fighting for survival.

Plath first attempted suicide in 1953 at the age of 21. Her disappearance made the local news and, as Literary Hub notes, resulted in her being committed to McLean Hospital for psychiatric treatment. (Her poem, "Lady Lazarus," documents the attempt, and there's a recreation her novel The Bell Jar.) This treatment eventually included electroshock therapy under Dr. Ruth Barnhouse, whom Plath came to trust, and seemed to have a happy and successful outcome.

After her marriage to Ted Hughes began to fall apart, however, Plath sank into a fresh depression. Discovering his affair with mutual friend Assia Wevill, Plath reportedly suffered fevers and breakdowns even as she wrote what would come to be regarded as her greatest poetry. As reported by The New Yorker, she moved with the children to an apartment in London and wrote in a letter, "What appalls me is the return of my madness, my paralysis, my fear." A week after writing that, Plath gave in to that madness and fear one last time, and the world lost a fierce, vibrant voice.

There were almost no obituaries

One of the most tragic aspects of Sylvia Plath's life was the way her death was almost ignored. As The Atlantic notes, at the time of her death, Plath was famous. She was a renowned poet and a published novelist whose debut book had just come out. She was married to an equally famous British poet, and their marriage had been treated as a celebrity match since its beginning. And yet, when Plath died, there were almost no official obituaries to mark the event.

According to author Peter K. Steinberg, this might have had something to do with the fact that her death came as the result of suicide. He speculates that her mother found suicide to be shameful and wanted to keep the details out of the public eye. Another disturbing possibility is simple sexism. In the early years of their marriage, when Ted Hughes was a rising literary star, Plath was frequently referred to as "Mrs. Hughes" or simply Ted Hughes' wife. Steinberg speculates that many people didn't realize that Sylvia Plath and Sylvia Hughes were the same person. In other words, the sexism of the time may have helped to erase Plath as a separate individual.

Whatever the reason, when one of our greatest modern writers died, almost no one took notice.

Ted Hughes tried to erase Sylvia Plath's legacy

For a long time after Sylvia Plath's death, you would have been hard-pressed to identify a more widely reviled literary figure than Ted Hughes. (For years, people regularly vandalized Plath's tombstone to remove Hughes' name.) Fair or not, his infidelity and treatment of Plath in her final years was seen as a key factor in her resurgent depression and tragic death. Worse was the suspicion that Hughes worked to sanitize his reputation by destroying many of Plath's papers — including poems and an unfinished novel that painted him in a bad light.

As Electric Literature explains, Plath mentioned a novel variously titled "Doubletake" or "Double Exposure" in her letters and made it plain that the book took inspiration from her own marriage, writing that it was about "a woman whose husband turns out the be a deserter and a philanderer although she had thought he was wonderful and perfect." After her death, Hughes became her literary executor, and while he published many of her poems in the ensuing years, he altered some, and no new novel ever appeared. He claimed in 1977 that the manuscript had "disappeared" seven years earlier, but Hughes' story continued to change, and in 1982, he admitted that he had destroyed at least one of Plath's journals because he didn't want their children to read it. Hughes' constantly shifting narrative has led many to believe he destroyed anything that made him look bad — including Plath's incomplete novel.

Sylvia Plath's son also committed suicide

Depression is a disease that can be passed on, and it often works slowly. When Sylvia Plath gave in to it in 1963, she left behind two children: daughter Frieda and son Nicholas. Their father, Ted Hughes, raised them, eventually remarrying in 1970. By all accounts, Plath loved her children very much and in fact wrote poetry about them — in one poem, she described Nicholas: "You are the one/Solid the spaces lean on, envious/You are the baby in the barn."

Hughes didn't tell the children how Plath died until they were teenagers, and tragedy seemed to dog the family for a while. As The Guardian reports, Assia Wevill, the woman Hughes had an affair with while married to Plath, killed the daughter she had with Hughes and then herself — an event that must have had a tremendous impact on Frieda and Nicholas.

Plath wouldn't have the chance to watch her children grow up, but she was spared witnessing their own tragedies as well. According to The Independent, Nicholas flirted with poetry as a teen but abandoned any thoughts of following in his parents' literary footsteps and pursued a career as an evolutionary ecologist instead. In 2009, 46 years after his mother's death, Nicholas Hughes committed suicide while pursuing his scientific work in Alaska.