Messed Up Things That Happened During World War I

In 1914, a series of interconnected events set off a military conflagration so huge it eventually became known as the First World War, aka the Great War. World War I changed everything about warfare, from the equipment to the tactics, and permanently altered the map, as the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian empires all collapsed by its end. Over the course of its four years, World War I claimed roughly 14 million military and civilian lives, cost the combatants more than $300 billion, and introduced us to the concepts of shell-shock, post-traumatic stress disorder, and chemical warfare.

At the time, people considered the devastation of the Great War to be such that it would be the last war ever fought — the "war to end all wars," which, sadly, wasn't exactly true. But as terrible as all that is, it only scratches the surface of the weird, messed up things that happened during World War I. From child soldiers to urine-soaked socks, here are some of the craziest things that actually happened during one of the deadliest conflicts in world history.

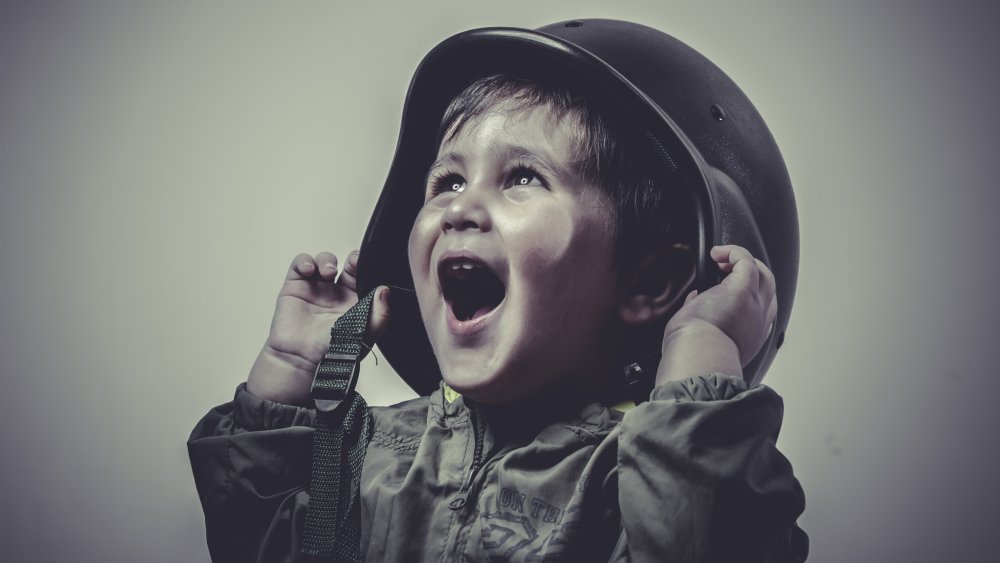

A 12-year-old boy somehow enlisted

War has always held a bizarre romance for some, and patriotism always spikes when a nation marches off to battle. While there's no shortage of stories of brave teenagers faking their age in order to get in the action, the story of Sidney G. Lewis is incredible because he wasn't some nearly adult teenager fudging his age a little — he was just 12 years old when he enlisted, shipped out, and fought on the front lines of World War I.

As The Telegraph reports, Lewis enlisted in the British Army in August 1915, and by June 1916, he was fighting on the Western Front in France as part of the 106th Machine Gun Company. While there were some doubts as to the truth of Lewis' story, Army records confirm it — the boy claimed to be 19 years old and to work as a tailor. He was examined by military doctors, and his enlistment was accepted.

Local historian Michael Page writes that Lewis served his country until his mother, a year or so late, figured out where he was and wrote the Army with a copy of his birth certificate. The boy was discharged and back in England by September 1916. (There's no word on whether he was grounded upon his return.) Lewis served his country well — his final rank is recorded as Lance Sergeant, typically a field promotion given to a corporal so they could take on the role of a full sergeant.

Desperate men lived in the abandoned trenches

One of the most enduring images of the First World War is trench warfare — thousands of men living in muddy, filthy trenches dug into the earth, often only a few feet away from the enemy trenches. Aside from the horrifying dangers they endured when having to go over the top facing brutal machine gun fire, there was the day-to-day misery of living in cramped, disease-ridden troughs in the dirt.

Worse, though, was when the soldiers moved on, leaving behind ruined farms that couldn't produce any food and endless earthworks — in which deserters, thieves, and other desperate men lived, scavenging corpses for supplies and living like animals. As Smithsonian Magazine explains, many soldiers told tales of these so-called "ghouls" who would emerge at night to pick through the unburied dead and abandoned supplies — and would sometimes fight each other for the spoils. Many of these men were believed to be deserters, soldiers who lost their nerve or simply decided getting killed for their country wasn't as cool as they'd been told but who had no way to get home.

One man, Lieutenant Colonel Ardern Arthur Hulme Beaman, wrote a memoir (The Squadroon) in which he described "no man's land" between the trenches as populated by "wild men, British, French, Australian, German deserters, who lived there underground, like ghouls among the moldering dead, and who came out at nights to plunder and to kill."

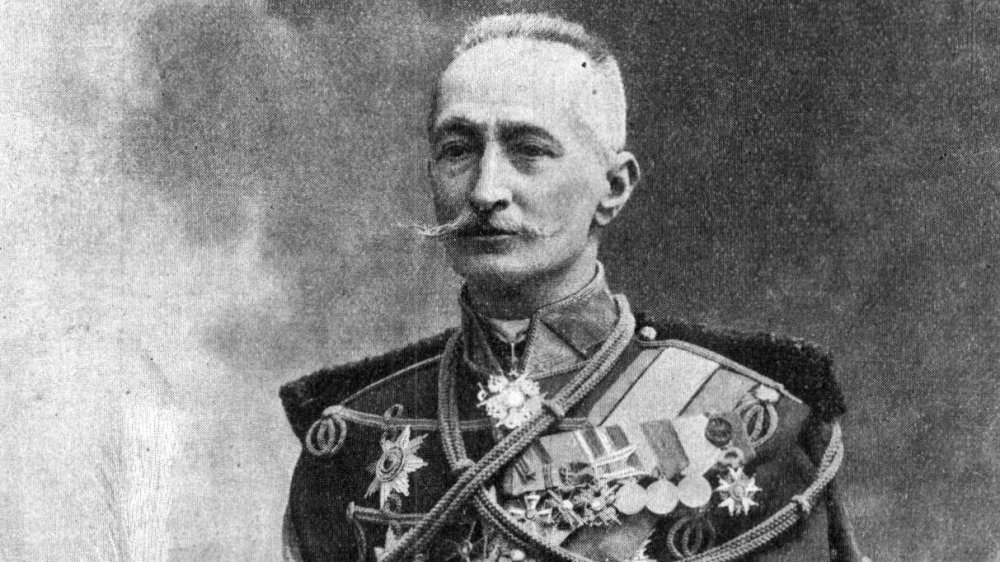

The Brusilov Offensive killed two million in two months

The scale of death and destruction that World War I inflicted on the world was unprecedented in terms of casualties and destruction of property and other resources. To put it into perspective, here's a thought experiment: Imagine two million people. Now imagine they all die within eight weeks.

That's what happened in 1915 during the Brusilov Offensive, led by Russia's General Aleksey Brusilov against the Austro-Hungarian forces. As The Irish Times reports, Brusilov's army of 600,000 — meticulously trained using full-size replicas of the defenses they would encounter — were remarkably successful in an offensive that most military commanders — including Brusilov's own Russian peers — thought doomed. He conquered a huge amount of territory in a relatively short time and pushed the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the brink of collapse. If the Russians had possessed the resources to follow up on this victory, the war might have ended much earlier and much differently — and might have preserved the Russian Tsar's position and avoided the coming Bolshevik revolution.

The cost was enormous, however. Estimates of the casualties total more than two million dead, including 40,000 killed in a single day according to author Timothy Dowling. Typically for World War I, the huge amount of bloodshed and destruction accomplished almost nothing beyond weakening the Austro-Hungarians and thus, ironically, ensuring that the war continued.

The French built a fake Paris during World War I

World War I saw a lot of innovation and technological advancement as mankind came together to figure out better, more efficient ways of killing each other. Among the many new frontiers explored by the military powers of the world was aerial warfare. The first flight conducted by the Wright Brothers happened in 1903 – according to Air & Space, the first aerial dogfight between two planes happened just 11 years later in 1914.

It also didn't take long for air forces to hit upon the idea of dropping bombs from the air, although a lot of those bombs were actually dropped from zeppelins instead of planes. Either way, France had good reason to worry about Paris. There was no way to detect approaching aircraft at the time, and as airplane technology improved over the course of the war, defending Paris from German bombers became a priority. So, as The Telegraph reports, in the final months of the war, the French did the sensible thing and built a fake Paris to draw German bombers away.

Built just to the north of the city, the fake Paris was designed to fool pilots, recreating the Champs-Élysées and Gare Du Nord and other famous landmarks. A lot of detail was put into the project, but it was never actually tested — the war ended before it could be used, and it was quickly torn down.

Dr. Doolittle was born in the trenches

For the soldiers serving in the trenches of World War I, the horrors they witnessed were psychologically crippling and difficult to talk about. Many sought to shield their loved ones at home from the brutality and violence they had to endure on a daily basis.

One such soldier was a man named Hugh Lofting. Lofting enlisted in the Irish Guards when the war broke out and left his wife and two children behind. According to The Sun, his wife asked him to write to his son and daughter about life in the trenches, but Lofting was reluctant to write his children about death and disease or the simple misery of life during warfare. The New England Historical Society writes that Lofting sought to protect his kids from these horrible truths, so he began writing stories about a well-dressed man who learned the languages of animals — the famous Dr. Doolittle. His son, Colin, stated that Lofting was also moved by the plight of animals that were injured in the course of the battles and wanted to imagine someone who had the power to help them.

Lofting suffered PTSD after he was injured and discharged, and modern-day doctors have actually studied the Dr. Doolittle stories to see how soldiers deal with the trauma of war through stories and other techniques.

Marie Marvingt had to disguise herself to fight

By the time World War I broke out, Marie Marvingt was 39 years old and already one of the most accomplished people in history. A tremendous athlete, Marvingt had won many prizes and set several records as she swam, cycled, climbed mountains, ballooned, and fenced — plus a dozen other sports and physical activities. As author Rosalie Maggio notes, she was dubbed the "fiancée of danger" by the French press and was a major celebrity in France. Marvingt also became a pioneering female pilot, the first woman to fly solo in a plane in 1910 and just the second woman to earn a pilot's license.

When the war broke out, women weren't allowed to enter the armed services, so BBC News reports that Marvingt did the only sensible thing: She disguised herself as a man and joined the infantry. Her athleticism made it easy for her to get through training, but she only managed to serve for ten days before her ruse was discovered and she was discharged. Undeterred, Marvingt traveled to the Dolomites and unofficially joined an Italian regiment.

In 1915, the French government, in need of experienced pilots, gave Marvingt permission to fly bombing missions — possibly making her the first woman to fly a combat mission. She excelled at that, too, and earned the Croix de Guerre for "heroic deeds."

A country was accidentally created during World War I

War is confusing. Populations get shifted, governments flee or collapse, and landmarks are blown up. The aftermath is often just as confusing as the actual battles, as the residents of the Wisper river valley in Germany learned. This area, which contains the towns of Lorch and Kaub as well as several smaller villages, had a population of about 8,000 in 1919, when the victorious Allies were carving up what had once been the German Empire for temporary administration. As told by map expert Frank Jacobs, the Americans and the French each created a sphere of influence on the map, but due to an error, the spheres didn't actually overlap, leaving a sliver of Europe outside either's jurisdiction.

Instead of being upset, the folks of the Wisper Valley banded together, declared themselves an independent nation, and elected a president. From 1919 to 1923, the so-called Free State of Bottleneck made efforts to convince the world that they were a real, live country — but the world regarded them as a mistake, refusing to let trains stop in the region and never recognizing their diplomatic overtures.

The Free State was subsumed back into Germany in 1923, officially. Unofficially, as The Wall Street Journal reported in 2015, the Free State continues to maintain a shadow government and continues its efforts to be recognized as an independent nation — though some suspect those efforts have more to do with tourism than a real spirit of independence.

The Christmas truce made the generals nervous

Even those only casually familiar with World War I have heard of the Christmas Truce, December 25, 1914. That day, English and German soldiers voluntarily put down their guns, promised not to shoot each other, and had a little holiday party in the area between the trenches known as "no man's land." Gifts were exchanged, songs were sung, and for one bright moment, humanity came together in brotherhood.

It's an inspiring story, and many still see it as proof that true peace on Earth can be achieved. But as Time Magazine notes, the Christmas Truce was part of a larger trend that the powers-that-be found alarming — and sought to suppress. There were actually a lot of little unofficial truces like this. Typically, it involved brief periods where soldiers unofficially agreed to a cease-fire to collect the dead and injured, but sometimes, larger-scale truces happened.

Some generals worried that "troops in trenches in close proximity to the enemy slide very easily, if permitted to do so, into a 'live and let live' theory of life." In other words, they might start refusing orders to kill each other. Many of these generals took steps to prevent that from happening and worked to forbid or disrupt any such truces — and notably, there aren't any others of the scale of the 1914 Christmas Truce throughout four more long years of war.

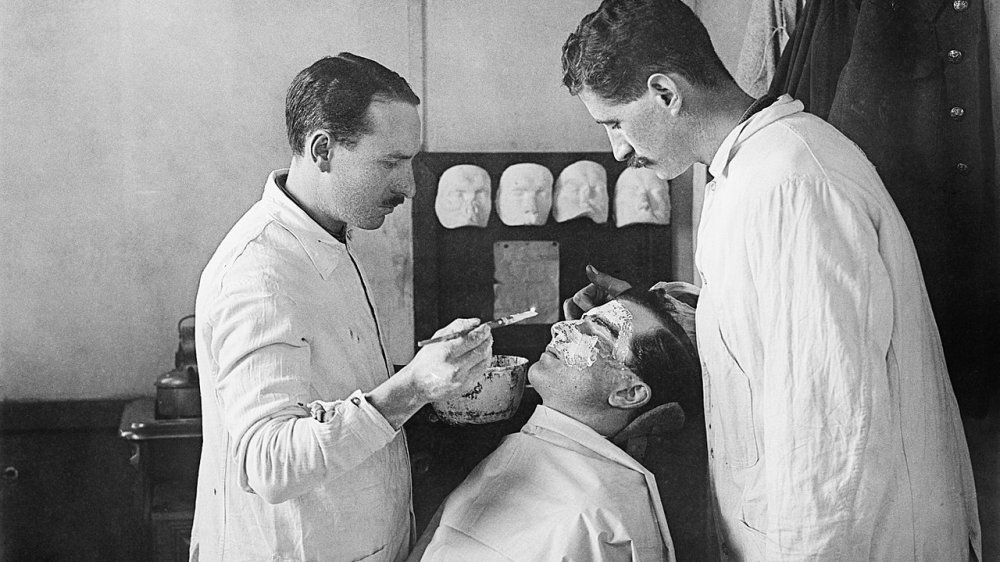

Facial injuries -- and masks -- were common

World War I was different from all the wars that proceeded it in terms of technology, tactics — and injuries. According to The Atlantic, one of the most horrific of these new types of injuries stemmed from trench warfare: When soldiers popped up over the edge of the trench to observe the battlefield, they often came back down with facial injuries — missing jaws, noses, and worse.

These injuries were rarely fatal, but they resulted in horrible disfigurements at a time when reconstructive surgery was in its infancy. Such injuries were considered so terrible that they actually qualified a soldier for a full lifetime pension, on the understanding that they would never be able to support themselves.

The only solution at the time was a mask — as Smithsonian Magazine writes, England actually established the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department to produce masks that were sculpted as much as possible to resemble disfigured soldiers' actual faces. The masks were made of extremely thin copper in order to be lightweight and were attached like glasses using the ears. While these masks wouldn't fool anyone up close, they enabled thousands of disfigured men to step back into public life with the terrible scars of their wartime experience hidden from view.

Soldiers used urine-soaked socks as gas masks

One of the dark gifts that World War I gave the world was our first taste of chemical warfare. On April 22, 1915, the German Army deployed chlorine gas for the first time. The gas, which had a greenish-yellow color and the familiar smell of bleach, choked and irritated soldiers, asphyxiating many. (However, as the Science History Institute explains, chlorine gas had nothing on phosgene, which was colorless and would cause soldiers' lungs to fill with liquid about two days after exposure, drowning them in their own fluids.)

Gas attacks became a common event in World War I very quickly, and soldiers initially had no defense against them. In fact, the first task the Allied forces faced was identifying the gas the Germans were using, which they eventually did by noticing how the brass buttons on uniforms had been tarnished, indicating the presence of chlorine. BBC News reports that in the earliest days of gas warfare, soldiers were instructed to soak a spare pair of socks in their own urine and tie them around their faces. The theory was that the ammonia in urine would neutralize the chlorine — but the fact is that the chlorine actually reacted with the urea in urine, giving off other poisonous fumes.

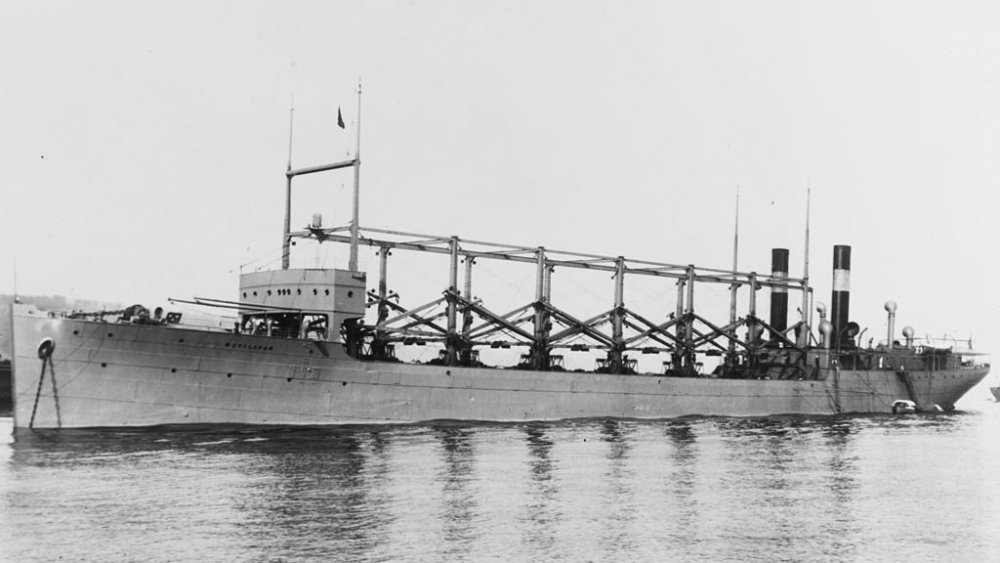

The USS Cyclops vanished without a trace

While trenches and ground warfare are what most people think of when the subject of World War I comes up, there were plenty of other theaters — and plenty of messed up stuff happened on the sea and in the air. One example is the USS Cyclops, an American vessel with a cool name that may have been a victim of the notorious Bermuda Triangle.

The facts, as reported by the Navy Times, are these: The Cyclops was the largest and fastest refueling ship in the Navy. It could haul 12,500 tons of coal at a time and had several large guns for defense. It left the Caribbean in March 1918, headed for Baltimore with 309 people on board — and never arrived. No sign of it was ever found, and no clue as to what caused it to disappear ever came to light. It remains the largest loss of life outside of combat in the US Navy.

Theories tend to center on the coal: Hauling coal and refueling ships at sea was dangerous, fires were common — and nearly 13 tons of coal can do a lot of damage if it catches fire. But if the ship caught fire, or even if there was a massive explosion, you'd expect some signs of the ship to be left behind. As it stands, we may never find out what happened.

The German Army murdered civilians

War requires armies to move through, and sometimes hold onto, unfriendly areas where the civilians might not be too happy to see them, but civilians are usually afforded certain protections in warfare as noncombatants. The German Army had a different idea in World War I. As author Ian Stewart writes, "German policy was based on Schrecklichkeit ('dreadfulness' or 'frightfulness'). During their advance through Belgium in 1914 the German Army massacred hundreds of civilians and burned down towns and villages in reprisal for acts of resistance, real or imagined, and to deter the population."

One of the most unforgivable acts of the German Army during World War I was part of what has become known as the Rape of Belgium. As the Germans invaded the small country, they engaged in numerous acts of brutality against civilians. Historian Barbara Tuchman describes one of the worst, which occurred in the town of Aerschot. The Germans, angry at perceived attacks conducted by the civilian population, decided to send a message, so they lined up 150 innocent people and shot them — the first of many such mass executions, the worst of which happened in a town called Dinant, where 664 people were killed.

Tuchman reports that in many Belgian towns, there remain rows of gravestones marked "Shot by the Germans" — some dating to World War I, some dating to 1944, when the German army returned during World War II.