What Life Was Really Like For Women At Versailles

In the 1670s, the infamous ruler of France Louis XIV, the Sun King, decided to transform his dad's hunting lodge into a domicile more suitable for someone of his stature. So the palace of Versailles was born. Louis then moved his entire court there, and the rest is history.

The idea was for Versailles to be a place where the king could get away from Paris, with its filth and crowded conditions. But the magnificent palace became its own cesspit. Living there, the aristocrats had nothing to do but get in each other's business, bicker, and try to keep themselves — and the king — entertained.

This led to an interesting experience for women in particular. They lived in the seat of political power but had none of it themselves, the rules and regulations for them were more stringent than for men, and to survive at Versailles required accepting and then mastering a very peculiar lifestyle. This is what life was really like for women at Versailles.

Childbirth was a palace-wide affair at Versailles

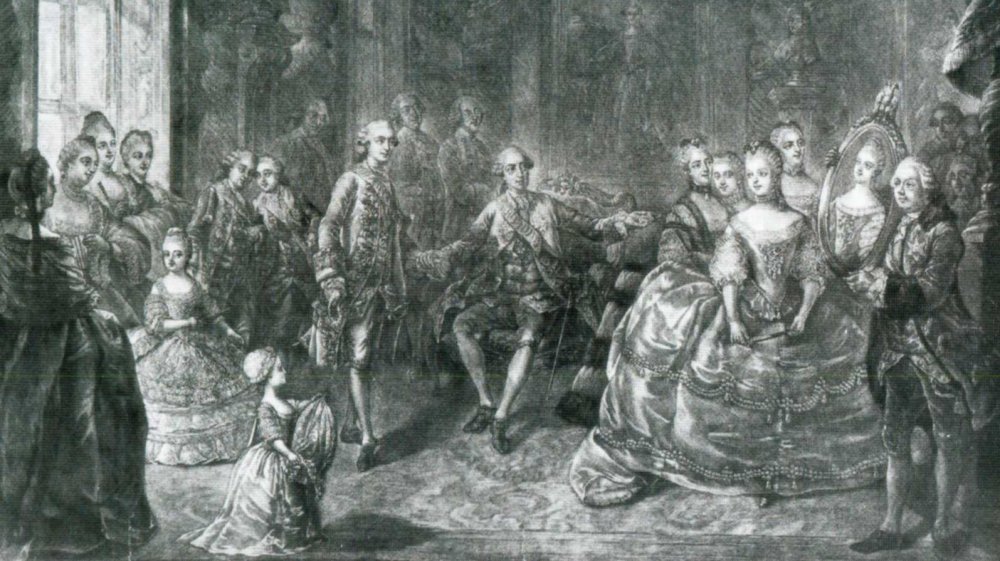

Being royal came with tons of perks, but if you were a royal woman, that also meant your body, particularly your womb, was property of the state. What came out of it was so important, privacy wasn't even a consideration. The queen, as well as any royal princess, had to give birth in public, according to This is Versailles. That might sound scary, but the official website of the palace assures readers the word "public" is "misleading." Not any old person got to watch the royal ladies squeeze a human out of their bodies, because "only doctors, ladies in waiting, the governess of the Princes and Princesses of the Realm, the Princesses of the royal family, and a few members of the church were allowed to enter." Oh. That's fine then.

Don't worry, any old person got to get in on the action pretty quickly, though. Once a royal woman went into labor and the doctor was called, the whole of Versailles knew what was happening almost immediately. So those not important enough to be in the room when it happened waited just outside, and once the kid was born, everyone from dukes to servants to guards trooped through the royal lady's bedroom to say congrats.

And if you're thinking there was an easy way of avoiding having your personal life invaded like this by just not getting pregnant, well, about that: When a married royal lady wasn't pregnant, the whole court spent their time talking about the "regularity, consistency, and quality" of her period.

Clothing was essentially torture at Versailles

When Louis XIV informed all his nobles they were moving en masse to Versailles in the 1600s, it was a hunting lodge in the middle of nowhere, far from the shops of Paris. According to A Short History of Europe, 1600-1815, an "army" of tailors, wigmakers, dressmakers, and goldsmiths soon sprang up around the new palace, ready to assist the rich people in fighting it out through fashion.

While even men had to be done up to the nines, the women of Versailles had it so, so much worse. Their clothing, especially the most formal outfits worn during important ceremonies, was crushing, literally. Dress in France in the Eighteenth Century says women were expected to wear a rigid whalebone corset that was so painful, it took literally days of training before they could stand the agony enough to don one in public. Skirts could be 12 feet in circumference and made of up to 30 yards of fabric. And you couldn't just waddle around under all that weight: Women at Versailles were expected to do a special walk of tiny steps that made it look like they were gliding across the floor.

When Marie Antoinette got to Versailles in the mid-1700s, she took women's fashion to a new level, at the same time that giant hairstyles came into vogue. Now ladies were also expected to get feet of height on their hair, which was achieved through pillows, hair extensions, and lots of ornamentation. Be thankful for sweats and a ponytail.

Gossip was a full-time job at Versailles

The history books sometimes mention some notably nice, kind woman who lived at Versailles, but they all usually fled to a convent before long, choosing the life of a nun over staying in the pit of vipers that was the palace. Louis XIV knew what he was doing when he threw together all the people who might challenge him: In the cramped conditions where everything was a competition, they turned on each other instead. To survive in this mini-village of up to 10,000 very rich, very powerful people took having some low morals.

Gossip was the ultimate weapon. Littell's Living Age recorded, "Gossip could not be more rife, or slander more virulent than it was at Versailles." If you wanted to move up in the world, and someone was in your way? Just start a rumor about them, since "cleverly veiled innuendos and graceful insinuations did the work of destroying reputations." Marie Antoinette's dear friend the Princesse de Lamballe – who would stand by the queen until the very end and be literally ripped to pieces by the Paris mob for her loyalty — even fell out of favor for a time because one Madame de Polignac "hinted, ridiculed, and insinuated" until she succeeded in undermining their relationship.

And gossip could have serious consequences. As well as the possibility of losing positions and livelihoods, some demanded satisfaction for insults. This is Versailles reports the Comtesse de Gacé faced so much slander thanks to rumors that she threw orgies that her husband fought a duel over it.

Versailles toilet etiquette, or lack thereof

Versailles was a massive palace of 700 rooms and acres of gardens. And by 1789, the year of the French Revolution, it had just nine flushing toilets. Almost all of them were for the exclusive use of members of the royal family. But even getting a hold of a chamber pot when you needed one could be difficult: This is Versailles says there were only about 300 of those as well. So what did one do when the call of nature came? You just ... went. Even the women.

The duc de Saint-Simon, in his Memoirs of Louis XIV and His Court and of the Regency, told the story of the Princesse d'Harcourt, who would eat and drink too much and then promptly "relieve herself from the effects thereof," which drove the servants who had to clean up after her crazy. But she was "never in the least embarrassed" and would just say she'd been unwell. He also reported she wouldn't even stop walking before letting it rip, dribbling along for someone else to worry about.

Even if women insisted on not peeing anywhere the fancy took them, they would witness men doing it constantly. It was said the king could even take a leak while driving a carriage. All this human waste everywhere meant the fanciest palace in Europe stank to high heaven, so women carrying fans, smelling salts, and bouquets of flowers was probably less about fashion than just making it through the day.

Extramarital affairs were expected at Versailles

The idea one would be faithful to their spouse at Versailles was laughable, and women had just as many affairs as men. Unless you were the queen, of course. Then having a boyfriend was essentially treason. This didn't necessarily stop them, though. Marie Antoinette is thought to have had at least one long-standing relationship with the Swedish count Axel von Fersen.

Less important women could have affairs with much less scandal, and the ultimate prize was the king himself. According to History, it wasn't just understood that the king would have a mistress, it was also an official position: the maîtresse-en-titre. The job came with huge perks: a great apartment in the palace near the king's, tons of respect, and the power to dispense favors to the little people. Your children could be recognized by the king and given titles and land. Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV, lasted in the position for 20 years and gained immense political power. She even essentially fought the Seven Years War for her royal lover. (Although that's not really something to brag about; it didn't end well for France.)

But being at the top meant everyone at Versailles was trying to bring you down. Families would try to get their attractive daughters to catch the king's eye, always hoping they might move up in the world through bedroom antics. One of Louis XIV's official mistresses, Louise de La Vallière, found it all too much and gave everything up to become a nun.

Fighting for royal favor at Versailles

Part of the point of bringing all the aristocrats to Versailles in the first place was so they could be on hand to serve the royal family. For women, this meant getting close to and finding favor with the queen. For a gender that had almost no power or authority, becoming an official part of the queen's court meant serious respect. According to Vienna and Versailles: The Courts of Europe's Dynastic Rivals, 1550-1780, these were official positions, with titles, honors, rules, and perks. If you couldn't get a job with the queen, then roles in the courts of other royal women could be a consolation prize.

And women at Versailles "played a central role in the patronage system." Any woman close to the king, from his mistresses to his sisters, could tell him who to appoint to positions, male or female.

Courtiers fought fiercely for the right to serve the royals. Some roles were inherited, while others could be bought, but many were just given out by a particular royal to friends, patrons, or someone who caught their attention for being notably beautiful or intellectual. There was good reason to tear and claw for these positions: The Princesse de Lamballe, for example, was made Superintendent of the queen's household. This meant everything had to go through her, kind of like a Chief of Staff — a huge amount of power. She received a truly staggering yearly allowance, as well as a large suite of rooms at Versailles.

Performing got really meta for women at Versailles

Everyday life was a performance at Versailles, involving innumerable complex bits of etiquette, acting nice to important people you might hate, and dressing the part. So it must have been very meta when courtiers found themselves required to perform roles onstage as well.

According to Bachtrack, Louis XIV loved the type of dance that was quickly being codified into what we know as ballet, and in 1681, he allowed women to join him in performing it for the first time. No one could be a better dancer than the king, obviously, but doing poorly was also not an option, and practice was required to get good enough. These amateur ballets including the ladies of the court were often performed to celebrate major events, like the birth of a king's child or the wedding of an heir.

Marie Antoinette loved performing plays so much that she eventually had a whole fancy theater built so she and her friends had a permanent place to do amateur dramatics, per Versailles' official website. Inspired to start performing when a war meant there were fewer people and less amusement at the palace, The Life of Maire Antoinette says the queen started her own company made up of her friends. Originally, the plan was to only let one man join them, but this seems to have been dispensed with pretty quickly. They put on plays for years, often with the king in the audience, and were generally considered decent actors.

Hunting at Versailles was fun for all genders

Considering Versailles started life as a hunting lodge, it's no surprise that killing wild animals was still a fun pastime for the people there once it morphed into a huge palace. According to Live Science, there was even a special ceremony involved when the king put on or took off his hunting boots. Louis XVI was particularly obsessed with hunting, to the point it was almost an addiction. If a woman wanted to get chummy with the king, participating in a hunt was a great way to do it.

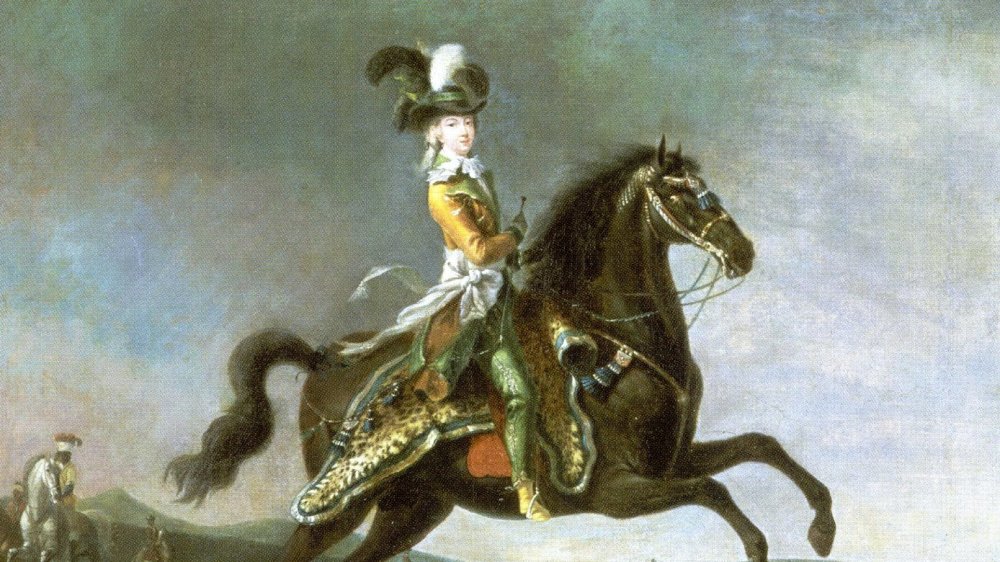

Author Geri Walton records that we have proof Marie Antoinette sometimes went hunting with her husband, from a description of an Englishman who also attended one outing. The king's sister Madame Elisabeth was there for the blood sport as well, and unlike the queen, who rode in a carriage, Elisabeth rode a horse and was decked out in the latest fashionable hunting outfit. Since wearing a skirt and riding sidesaddle would make hunting difficult, it was acceptable for women to wear breaches while chasing a poor animal to its death.

Hunting was so much a part of life for women at Versailles that many chose to have their portraits painted as if the artist had caught them during a pursuit. Some just posed in hunting outfits while others, like Marie Antoinette (pictured), were portrayed on their horse mid-event. Women also had special guns designed for their gender and exchanged them as gifts.

Letter writing took up a lot of women's time at Versailles

One of the most time-consuming activities of the past — one that is often overlooked when thinking about our ancestors' daily lives today — was letter writing. The New Biographical Criticism says by the time of Versailles' construction, travel was becoming easier and more common, plus the process of sending and delivering mail was getting streamlined. This meant people often needed to communicate with others far away and had a way to do it, so letter writing exploded.

According to Chambers' Edinburgh Journal, Fredrick the Great called the French "the first letter-writers of Europe." And there were just so many different types of letters one could busy oneself with. Women at Versailles needed to let their friends in Paris and other places know all the gossip at the seat of power. Foreigners, including those women who married into the French royal family, needed to write home. There were thank you notes for everything, including when Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, who hadn't conceived a child after years of marriage, wrote her brother a note of gratitude after he explained the birds and the bees to them. There were love letters to your affair partner, too — tons of them — like the ones Marie Antoinette wrote to Count Fersen in a complex code, or even anonymous letters, in the hope of ruining a rival's reputation.

There were so many letters that some women even published their own as memoirs, which were extremely popular with readers.

The women of Versailles were addicted to gambling

Hanging around Versailles, never allowed to leave or you could kiss any importance you had goodbye, just dressing up and complaining about everyone else all day could get really, really boring. Perhaps nothing illustrates how rudderless European aristocrats in general were in the 17th and 18th centuries than the fact that they all became full-blown gambling addicts. And the women were the worst of the bunch.

According to The Age of Chance: Gambling in Western Culture, gambling was "an integral part of life" at Versailles. Louis XIV saw games of chance as another way of turning his courtiers against each other and keeping them too busy with frivolities to challenge his rule, so gambling at the palace quickly became so "extravagant and intense" that Versailles earned the nickname "ce tripot" — gambling den. Knowing how to play the different games was so important to being a part of high society that social-climbing parents hired "gaming masters" to teach their children the different rules. This included any daughters, because it was just as important that they learned, if not more so.

At a time when women had no political say and usually no financial independence, gambling allowed them access to importance and their own money. Women led the fashion for new types of games of chance, and one sure way to get noticed by people who might not give you the time of day otherwise was to throw the best parties where everyone could throw away their inheritances.

Attending church at Versailles wasn't optional

Living at Versailles might have meant breaking all the rules in the Bible on a regular basis, but you were still expected to go to church. No matter how lax one's morals were in between church services, attending them — and being seen to attend — were of the utmost importance. Louis XIV considered himself the most important person in the Catholic Church, regardless of what the pope might have to say about that. He also persecuted those who subscribed to different Christian denominations. So showing up for mass and being super into the whole thing was self-preservation, in both a ethereal and very earthly way.

According Versailles' official website, "the King's mass" was every single morning at 10 am. Court ladies had their own section to themselves. The service lasted half an hour, with a new piece of music sung every day.

But church could be much more than once a day. The duc de San-Simon recorded a story about the infamous Princesse d'Harcourt: He said when she was visiting the palace of Fontainebleau (a kind of getaway from Versailles for the king), the princesse was convinced to play cards instead of going to evening prayers. After prayers finished, the king's official mistress caught her. The princesse cried, "I am ruined! She will see me playing and I ought to have been at chapel!" Then she fell out of her chair. So, all manner of debauchery at Versailles: fine. Skipping church: career-ending.