The Messed Up Truth About Hugo Chavez

Serving as the Venezuelan president from 1999 until his death in 2013, there are few modern political figures quite as polarizing as Hugo Chávez. A founder of the democratic socialist Fifth Republic Movement, and later a leader of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, Chávez promised an economic revolution brought through socialist change.

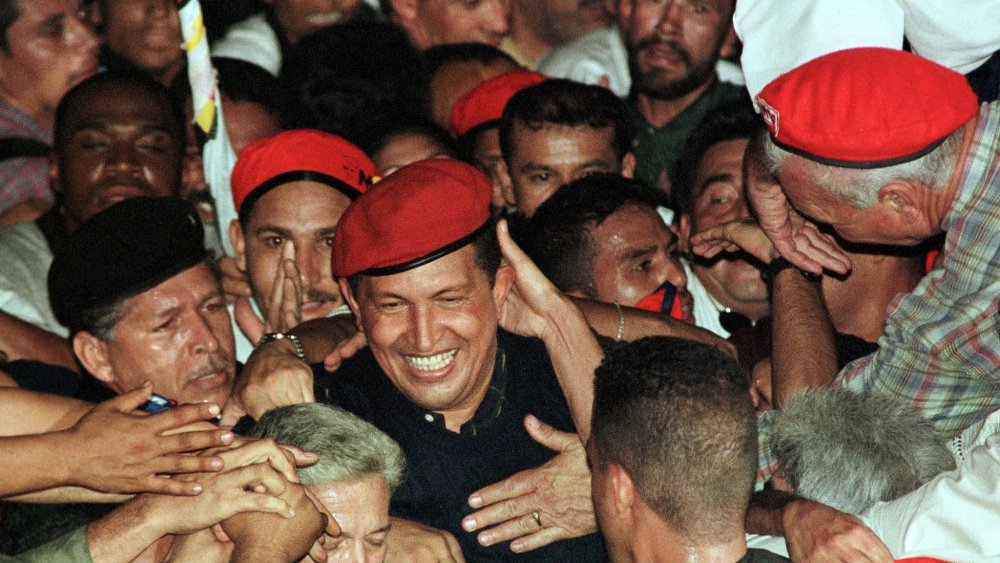

How'd he do it? Hugo Chávez was preternaturally adept at connecting with his base, the poor, while stirring up resentment toward Venezuela's wealthy elites. He was known as a natural orator, charismatic and mercurial. His followers — called Chavistas — became fiercely loyal proponents of their leader's socialist programs and strongman personality. Growing up dirt-poor in the Barinas state and with a mixed African, indigenous, and Spanish ancestry, Hugo Chávez was a unique reflection of his constituents.

However, Chávez wielded his influence in Latin America through divisive means. Taking a page from the autocratic playbook, Chávez ruled by stifling dissent, limiting the freedom of the press, seizing land, and harassing other world leaders. Here is the story of how the odd, intimidating, and ambitious Hugo Chávez rose to power and brought about the current Venezuelan crisis through an increasingly authoritarian rule.

Hugo Chávez's Bolivarian revolution begins

A former paratrooper, Hugo Chávez came into prominence after leading a failed military coup against President Carlos Andrés Peréz in 1992. As recounted by the BBC, Chávez and a group of fellow military officers had formed the Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement out of outrage with the Democratic Action party's austerity measures. The failed coup took 18 lives and injured 60. Upon giving himself up, Chávez was allowed to speak on national television to his comrades for a total of 32 seconds. According to the New Yorker, he said, "Comrades, the objectives we set for ourselves have not been possible to achieve for now." With that, Hugo Chávez solidified himself as a champion of the people who would one day push his revolution forward.

He served a two-year jail sentence for the coup, during which he adopted Marxist ideologies. The New Yorker notes that Chávez saw himself as the new Simón Bolívar, after the 19th-century revolutionary who called for Latin American unity. Chávez declared a "Bolivarian Revolution" and founded the Fifth Republic Movement party. When he ran for president in 1998, Hugo Chávez had excited the disaffected and impoverished with his promise of employment and economic recovery. With 56% of the vote, Hugo Chávez, who had once attempted to take over by force, had won by democracy.

Hugo Chávez cripples democracy

Once elected, Hugo Chávez set his mind to changing the constitution and consolidating power. Riding on an 80% approval rating in his first year, per Encyclopedia Britannica, Chávez redrafted a constitution that required new elections for every elected official nationwide. The results of this mega election included Chávez being elected for a six-year term, a pro-Chávez majority in the National Assembly, and a Supreme Court that was stacked with pro-Chávez judges. By late 2005, the Chávez administration had a stranglehold on the National Election Council and won a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly. Hugo Chávez could effectively change laws by decree.

With this carte blanche, Hugo Chávez nationalized industries like electricity and telecommunications. His administration also silenced dissenters with impunity. Human Rights Watch reported that Chávez once called for the imprisonment of judge María Lourdes Afiuni after she had let a government critic free during a trial in 2009. Afiuni was arrested, spent a year in prison in horrible conditions, and later put on house arrest. This type of government-led harassment was not rare for Hugo Chávez, a strongman who flouted international authorities and in 2012 pulled out of the American Convention on Human Rights.

With checks and balances stripped from the government, despite the electoral process, Venezuela had become increasingly authoritarian.

Hugo Chávez knew the power of oil

In the decades prior to Hugo Chávez's presidency, Venezuela had one of the biggest petroleum reserves in the world and boasted a per capita GDP much higher than its neighbors. With a stable democracy and riches of oil, you might think it would take a war to push Venezuela's economy off-course. Turns out, all it took was the ego of Hugo Chávez.

The state-run oil company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) made up 80% of the country's export revenues in 2002. Foreign Policy notes that, as oil prices were down globally, Hugo Chávez sought to cut production in the hopes that prices would get higher. Managers at PDVSA, however, wished to increase production and reinvest revenues back into the company's development. Not having any of that, Hugo Chávez replaced the president of the PDVSA with an ally. He also fired a handful of company managers on live television in a humiliating display.

With the company suffering from mismanagement, Chávez's opponents organized a strike with the state oil company that lasted two months. Naturally, Chávez fired the striking workers and replaced them with about 18,000 of his own unskilled, nonunion employees. Hugo Chávez now had complete control over PDVSA and could use the revenue to fund his socialist programs like housing and education — an admirable goal, but the result was a flailing PDVSA with no revenue to invest in production and expertise. Venezuela suffered from an economy that relied far too heavily on one resource.

Hugo Chávez was best friends with Fidel Castro

For Hugo Chávez, Cuban leader and Communist Fidel Castro was something of a mentor, ally, and inspiration. Chávez and Castro took turns doing each other favors throughout their careers. Fidel Castro relied on the subsidized oil prices Hugo Chávez offered Cuba to dig the country out of a financial hole. As noted by the BBC, as of 2005, Venezuela sent 90,000 barrels of crude oil a day at a preferential price to Cuba.

Meanwhile, Castro sent teachers, sports instructors, and doctors to Chávez's shores in an attempt to alleviate poverty. According to the New Yorker's Jon Lee Anderson, by 2001, tens of thousands of Cuban doctors had treated Venezuelans in a program Chávez called Misión Milagro (translated as the not-at-all-modest Miracle Mission). Additionally, about 50,000 Venezuelans went to Cuban shores for eye surgery in 2005.

Encouraged by Fidel Castro's brand of socialism, in 2015, Chávez declared that the way to happiness was through 21st-century socialism. It was a friendship that lasted throughout Hugo Chávez's presidency and one that made US officials deeply anxious about the future of democracy in their respective regions.

The 48-hour coup d'etat

On April 11, 2002, about a million people, upset with unfulfilled election promises and Hugo Chávez's changes for the oil industry, gathered outside of Chávez's palace to demand he resign. Pro-Chávez gunmen and the National Guard fought against the protesters, with both sides losing lives. According to CNN, 12 protesters were killed and dozens more were injured.

This violence led to a short-lived coup d'etat where the military established an interim leadership with Pedro Carmona, a Chávez opponent. But Carmona quickly suspended the constitution, and fearing they had put a right-wing dictator into power, the military then recognized former Vice President Diosdado Cabello as the leader on April 13. Cabello instantly brought Chávez back to his presidency – the coup lasting all of 48 hours.

The effect was a post-coup Chávez who was even more determined to wield his power in the face of opposition. Those who opposed him, as reported by Encyclopedia Britannica, he derisively called "escuálidos" or "scrawny ones," still held on to their grievances. The opposition forced a recall referendum in 2004 to remove him from office, but with growing popularity from his newly established social programs, Chávez remained in power.

The endless presidency of Hugo Chávez

The line between president and dictator gets pretty thin when term limits are thrown out. In 2007, Hugo Chávez proposed abolishing presidential term limits, but that effort fell flat. In 2009, he tried a new tactic: bribing governors and local officials with the abolishment of their own term limits. The 2009 referendum was a success, and Chávez pushed constitutional changes that made it legal for him to be reelected indefinitely. The Guardian reported that 54% of voters backed the referendum, and it set Chávez up for a lifetime rule. Hugo Chávez called his indefinite reelection the victory of the revolution and the people, clearing the way for the so-called "pink tide" left in Latin America. His opposition worried about the unlimited reach of his presidency and worried it would inspire the rise of dictatorships in neighboring Bolivia, Colombia, and Ecuador.

In total, Chávez was elected president four times between 1998 and 2012. Had he not died, there is no telling how long Hugo Chávez would have kept his power.

Helping FARC

In one of his most controversial stances, Hugo Chávez was a key aid to FARC throughout his presidency, despite publicly claiming otherwise. In 2009, according to the New York Times, intelligence communities obtained evidence that Hugo Chávez aided the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a guerrilla rebel group, by supplying them with weapons and refuge within Venezuela's borders. Venezuela was used as the rebel group's training grounds and opened up drug trafficking in the region for the group.

The evidence, recovered from a FARC computer, pinpointed collaborations between top Chávez officials and the guerrilla group, known for their attacks on infrastructure in Colombia. Why would Chávez want to hide this aid? In the US and European Union, FARC had been classified as a terrorist group. As reported by Insight Crime, a faction of the military known as Cartel of the Suns was thought to be trading cocaine for arms with the guerrilla group. The files from FARC commander Raul Reyes computer also alleged a meeting between Chávez and Reyes in 2000 where there was an explicit promise of funding. While the full extent of Hugo Chávez's relationship with the Colombian rebels is still unknown, it remains a hallmark complaint of Chávez's critics.

Hugo Chávez creates an unfree press

Given the hall pass of the perpetual presidency, Chávez began arresting his political opponents, gutting radio stations that spoke out against him, and filling the airwaves with his speeches and positive coverage. The government doled out penalties to websites and channels that spread messages that could "foment anxiety in the public," as noted by Human Rights Watch.

Chávez worked relentlessly to bully media outlets that fell out of line. In 2007, the government denied the private channel RCTV a renewal license and forced cable providers to take the channel off the air. Chávez attempted to pursue sanctions against Globovisión, the one remaining network decidedly critical of him. In fact, in 2009, pro-Chávez radical Lina Ron led a violent attack on the offices of Globovisión, as reported by the BBC.

According to the Washington Post, in 2004, Chávez passed a law allowing for the censure of media outlets by a newly created watchdog group, CONATEL. Another successful tactic Chávez employed was to force stations to be sold to his supporters — or shutter entirely. This top-level censorship gave Chávez exactly what he hungered for — complete control and a sense of perpetually being in his public's good graces.

Hugo Chávez TV

Extremely concerned with his own cult of personality, Hugo Chávez had a regular Sunday TV program called "Aló Presidente," which could run anywhere from four to eight hours. Completely unscripted, Chávez would appear in front of a live audience donning a military jacket and red beret. Chávez used the time to push his agenda, criticize his opposition, and at times, sing off-key.

Per the New York Times, a notable 2006 episode of the talk show featured Chávez, sitting at a desk in a cow field, openly criticizing US President George W. Bush's involvement in Iraq. Chávez dubbed Bush "Mr. Danger" and threatened war should he ever invade Venezuela.

Segments would often depict Chávez's revolution at work — trailing him to ribbon-cutting ceremonies and expropriations of land owned by "the bourgeois" for the state. Government officials would have to be on set just to keep up with any policies and decrees Hugo Chávez would make up on the spot. In 2008, for example, Chávez decided on live TV to send 10 battalions to the Colombian border after their army planned to assassinate a FARC leader Chávez had backed. Because "Aló Presidente" could go from zero to political crisis, it became essential viewing for Venezuelan citizens.

The whims of a tyrant

Since Hugo Chávez had total control of the state, the country became subject to his odd whims and arbitrary moral decrees. According to the New York Times, Chávez was a teetotaler and was extremely vocal about hating the country's consumption of Scotch whiskey and the popularity of breast enhancement surgeries.

He didn't drink Scotch, but Chávez was a complete caffeine addict. It was reported by the Times that, at his worst, he was downing 26 cups of espresso a day. That might have been because his psychiatrist, Dr. Edmundo Chirinos, interviewed in the New Yorker, revealed that Chávez only got two to three hours of sleep a night. Those close to him described his bottomless well of stamina and sense of martyrdom. Unlike other world leaders, Chávez refused to wear a bullet-proof vest during public appearances.

In one of his oddest moves as president, Hugo Chávez also decided to change Venezuela's time zone to 30 minutes behind its usual time. The change came in 2007, as reported by Reuters, when Chávez determined schoolchildren needed 30 minutes more morning sun.

Chávez also delighted in making inflammatory comments aimed at an international audience. At the United Nations General Assembly in 2006, Chávez famously called President Bush "the Devil." He also corresponded with Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, aka Carlos the Jackal, a Venezuelan terrorist who murdered French police agents in 1975, according to the New York Times. Why? He knew it would anger Europeans.

Hugo Chávez's hidden health concerns

Sometimes concealing health problems is a political strategy. Not wanting to appear weak or incapable of serving, many autocrats have been known to lie about illness. In June 2011, Hugo Chávez traveled to Cuba to have surgery on a tumor. He had cancer, but, Encyclopedia Britannica notes, the state would not release any details about what kind or the prognosis.

When Chávez underwent chemotherapy in 2012, there were questions about his physical fitness to run for president later that year. Still, Chávez insisted he was healthy enough for another term. Despite the concealed health concerns, he won his fourth election with a solid margin of 10 percentage points against his opponent Henrique Capriles Radonski. However, victory was short-lived. In December 2012, Chávez underwent yet another mysterious cancer-related surgery and appointed Vice President Nicolás Maduro as his successor in the event he didn't make it.

When Chávez was still recovering in Cuba by the time of his inauguration in January 2013, the National Assembly and Supreme Court, stacked with Hugo Chávez allies, voted to postpone his swearing-in ceremony — something virtually unheard of. Chávez succumbed to cancer on March 5, leaving Maduro as his interim successor. A special election was held that April, with Maduro beating out Capriles to serve the rest of his mentor's term.

Hugo Chávez's legacy of empty promises

Originally running on an anti-corruption, pro-employment platform, Hugo Chávez's ambitious social programs to uplift the poor were not entirely successful. His Bolivarian missions were funded by increasing oil prices enjoyed in the 2000s, bolstering his power. Programs to open up free clinics, develop housing, and provide food subsidies for the poor initially had a positive impact on literacy, healthcare, and poverty rates. However, in 2010, the economy began to falter and Chávez declared an economic war. Chávez's use of overspending and price controls had led to constant shortages of basic foods like milk, meat, grains, and coffee. The 14-year presidency left a devastating legacy: According to data collected by the Guardian, the homicide rate had nearly doubled and high inflation rates soared since 1999.

Hugo Chávez's economic policies had teed the country up for a collapse after a decade of high revenue. As reported by the Public Policy Initiative and the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, Chávez's nationalization of private business and overreliance on oil revenue for government funding had created an unsustainable economic strategy. It led to the horrific Venezuelan crisis of today, in which inflation rates continue to climb, blackouts are common, and 25% of the population lost 19 pounds in 2016 due to widespread hunger, per UPI. Chávez might no longer be in office, but the devastation of his populist, socialist policies still has a tight grip on the people of Venezuela.