The Reason The Founder Of Mother's Day Tried To Abolish The Holiday

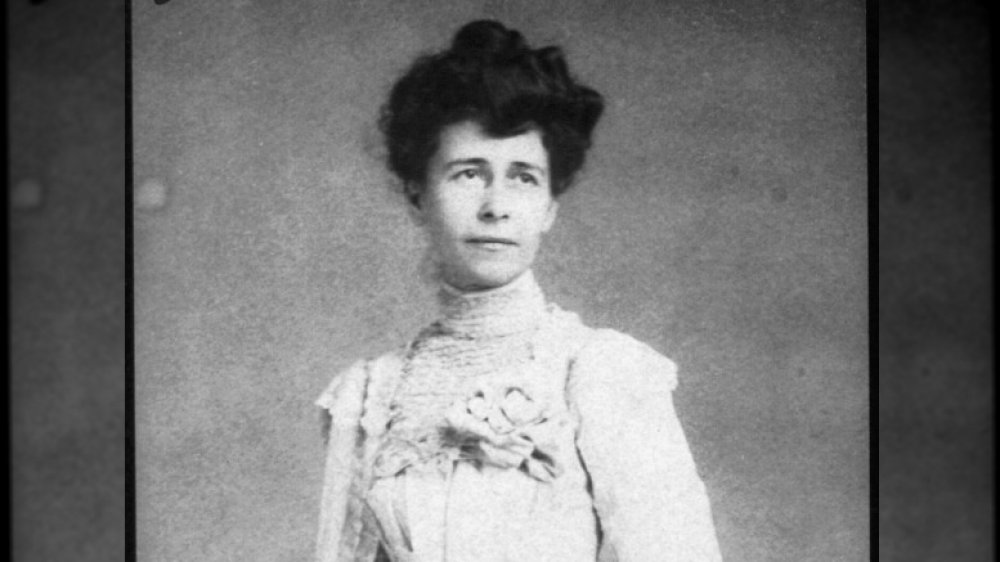

Perhaps it comes as no surprise that it took the Federal Government nearly 20 years to jump on the emotional and economic steamroller that is Mother's Day. Baseball, motherhood, apple pie, right? You'd think it was a lock. Not so much. Mind you, mothers were celebrated on the state level long before President Woodrow Wilson signed the legislation in 1914, making it a national observance, according to Smithsonian. But the whole country taking part? That was Anna Jarvis's brass ring. Jarvis had been campaigning for a national observance to honor mothers for a while. She had no skin in the game, so to speak — Jarvis had no children of her own, but was inspired by her own mother's hope that someday, motherhood would be honored and celebrated. When Jarvis's mother died in 1905, Anna went through the many condolence cards and the kind words that people had written, and found her calling in life. She made her case to anyone she thought might be of influence, from presidents to governors to Mark Twain.

Once established, business took notice, recognized the possibilities, and went to work. Jarvis's own symbol for the holiday was a white carnation — her mother's favorite, according to Mother Nature Network. The floral industry stepped in: if a white carnation is good, wouldn't a bouquet be better? How about other kinds of flowers? Greeting cards — especially greeting cards. Candy. (Brunch, apparently, came later.)

Mother's Day means billions of dollars every year; also, "I love you"

And Anna Jarvis was aghast. Horrified. And angry. Angry that people tried to commercialize a sincere expression of thanks and gratitude. Angry, later, that others tried to piggy-back on the holiday and use it to raise money for various charitable causes — she called them "Christian pirates," says National Geographic. Mother's Day, said Jarvis, should "be a day of sentiment, not profit," as Mental Floss tells us. She considered the holiday her creation, and she established the International Mother's Day International Association as a legal entity to protect the purity of the celebration. She wasn't afraid to sue those she considered exploiting the day for personal gain — she referred to the greeting card, florist, and candy companies collectively as "termites," among other things. If nothing else, she deserves credit for persistence.

There is a fine line between persistence and unhealthy obsession, as any family member of a Guinness World Record holder can tell you. Jarvis exhausted her own limited funds, first promoting the idea, then trying to protect it. She even shot down Franklin Roosevelt's design for a Mother's Day stamp. (Fun fact: Roosevelt was also an avid stamp collector.) In one of her final public appearances, Jarvis was seen "going door-to-door in Philadelphia, asking for signatures on a petition to rescind Mother's Day."

Eventually she was hospitalized at the Marshall Square Sanitarium in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where she died, penniless, in 1948, age 84. She never knew that her medical bills were being paid, in part, by a consortium of very, very grateful florists.