Creepy Things About Living In China

The People's Republic of China is about the same size as the USA, if you toss in Alaska. Of course, this Asian country has five times the population of the US. Governing a country that big, with that many people, requires some innovation ... and unfortunately, that sometimes comes along with a lot of coercion and deceit.

Granted, China isn't always a dystopian nightmare. You can have a Starbucks coffee while watching ESPN on your iPhone in a Disney theme park. And yeah, the geographical diversity and beauty is equal to the US. But at the end of the day, China can be a pretty scary place, with incredibly strict rules and guidelines when it comes to the most minor of details. In fact, life in China can sometimes feel pretty similar to an episode of Black Mirror. From everyday decisions to tracking apps, here are some truly creepy things about living in China.

In China, you need permission to move

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took control of a huge, mostly rural, and poverty-stricken country in 1949. Sitting right next to the industrial powerhouse of the Soviet Union and needing to recover from a century's worth of humiliation at the hands of colonial powers, China's leaders set out to modernize their new country. The best known of these policies was the Great Leap Forward, a calamity in which up to 45 million people died. Desperate for rapid industrialization, the government tried to balance the needs of industry and agriculture, largely by strictly restricting the free flow of resources, especially labor (i.e. people). Over 60 years later, this system is still in place.

Since 1958, the Chinese household registration system (aka hukou or huji) has separated Chinese people into rural and urban zones. Traveling between zones is controlled by limiting access to jobs, public services, education, healthcare, or food outside of residents' assigned zones. So a farmer can't just move to a city, and a city-dweller can't give it all up to raise alpacas. This has had extremely negative consequences for the health, education, and economic opportunities for China's hundreds of millions of poor rural citizens.

Former Bloomberg China Bureau Chief Dexter Roberts echoed the feelings of many Chinese when he called fixing hukou "a very, very key reform" for China's economic future. In 2019, the CCP was making moves towards this end but with the recent coronavirus-related lockdown of entire provinces, the future of hukou reform may be in doubt.

China only has five religions

People of faith may often find China outright hostile to religion. You only have five legal religions to choose from (Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism), any others are prohibited, and all religious activity is tightly regulated. Even then, your ability to follow a faith can be restricted suddenly and arbitrarily, and depending on what your ethnicity is, your faith can have you sent to camps, a la the Muslim Uyghurs.

Even though China's constitution specifically states that Chinese citizens "enjoy freedom of religious belief," religious believers can't join the Chinese Communist Party. "Party members are banned from joining religions." said Li Yunlong, a professor within the CCP's Party School, to China's Global Times newspaper in 2015. "Believing in communism and atheism is a basic requirement to become a Party member." This means, seeing as how the CCP is basically the government, that believers can't ever serve in government.

According to The Asia Dialogue, Chinese schoolchildren are taught at a young age that "religion is a 'feudal superstition' ... a remnant of the past that holds the country back and is responsible for many of its problems." So it's no surprise that over half of Chinese people are atheists. However, Religious beliefs are reported to be rising in China these days, despite a surge in recent years of claims of widespread attacks on religious believers and houses of worship.

The work schedule is intense

The last four decades have elevated China onto the world stage in an unprecedented way. Their economy has grown multiple orders of magnitude to become the second largest in the world. One of the oft-repeated reasons why is China's work ethic. Chinese workers put in long hours for low pay, and this is part of why China has become, as Investopedia puts it, "the world's factory." China's work culture is known as 996 — 12 hours a day (from 9 am to 9 pm), six days a week. Last year, China's richest man, Jack Ma of Alibaba (with a current net worth of $40.8 billion), gave a full-throated endorsement of 996, implying both his success and China's were a result of 996 culture. "I personally think that 996 is a huge blessing," Ma said on one of the company's social media accounts. "How do you achieve the success you want without paying extra effort and time?"

However, even before COVID-19 tossed pretty much every nation's economy into a tailspin, China was beginning to see a slow in growth, especially in its extremely important tech sector. One of the suggested reasons why is rebellion against the 996 work culture. One op-ed in China Daily last year argued that such a culture not only violates Chinese labor laws but is also harming the productivity and competitiveness of Chinese tech firms. Still, most observers agree that 996 isn't going anywhere soon and that it's still essential for China's continued growth.

Chinese journalists need to be a member of the Communist Party

China does a lot of things differently. For instance, in most of the world, journalists are expected, among other things, to be independent and impartial. In China, on the other hand, journalists are expected to "raise awareness of the rule of law" and "safeguard the country's political and cultural security, as well as social stability."

The requirement to protect social stability is why, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, China arrested and imprisoned more journalists than any other country in 2019. Upsetting the government's plans or efforts in any way can easily be interpreted to be causing social instability. Reporting that the government is actively spreading false information about the extent of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan could lead to social instability and end up with a citizen journalist live-streaming his own arrest, for example.

To ensure media outlets report responsibly, the CCP has increasingly added more regulations and requirements for Chinese journalists over the last seven years. In 2014, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television banned the press from using "various information, materials and news products that journalists may deal with during their work, including state secrets, commercial secrets and unpublicized information." The following year, the government announced that all members of China's press corps needed to be a member of the Communist Party or at least pass tests on Party doctrine.

Being a jerk can cost you in China

Social and political stability is of the utmost importance to the Chinese Communist Party. Social harmony is essential to their plans for economic development and maintaining legitimacy. To enforce this, the nation's founder, Mao Zedong, encouraged ideological compliance. And that idea is still going strong today. In 2007, the CCP came up with plans for a new, technologically focused, policy to enhance social cohesion and political acquiescence, and in 2014, they announced the first pilot programs.

It may seem like something out of a Black Mirror episode, but China's Social Credit System — basically an elaborate ranking system — monitors and punishes unsocial behavior like smoking in nonsmoking areas, bad driving, not visiting your parents, and littering. The various pilot programs and private/public projects offer incentives to act and think appropriately with things like discounted energy bills, deposit-less purchases and leases, lower interest rates, and higher matches on dating sites. Punishments include everything from public shaming to denying you the right to buy plane or train tickets, apply for certain jobs, and it can even limit your kids' education opportunities.

Because nothing destabilizes a one-party state like opposing parties (technically, there are other political parties in China, but they function in more or less an advisory role), membership in one can lower your score, and so can posting "fake news" (read: anything unapproved by the CCP), buying too many video games, and being in debt. However, the system is a huge technical challenge, which is why they need the help of Western companies.

The incredibly creepy leadership app

The cult of personality isn't just a great song, it's how we describe the unhealthy fealty citizens sometimes have for their leader. Notable examples from the last century include Joseph Stalin, Adolf Hitler, and Mao Zedong — the three competitors for highest death toll in history.

Naturally, not all such devoted rulers end up despots, but there's a tendency towards violent excess in most places we find the phenomenon. And that's why many in China are concerned about the following current leader Xi Jinping seems to have, and many outside China are worried about the extent to which Xi is exploiting and furthering his popularity.

In 2019, President Xi got the CCP to pay for and promote an app to teach citizens all about the Party leader and his policies (which should obviously be yours too). "Study Xi, Strong Nation" was one of the most downloaded apps on the year (even surpassing TikTok for a while) and is designed to be a super app, with everything from mobile pay options to video chat to Snapchat-type self-deleting messages. But the Open Technology Fund says the app is little more than "a backdoor to rooted devices, essentially granting complete administrator-level access to a user's phone."

Unfortunately, the South China Morning Post reported last year that the app "is shaping up to be the party's most successful propaganda effort to date."

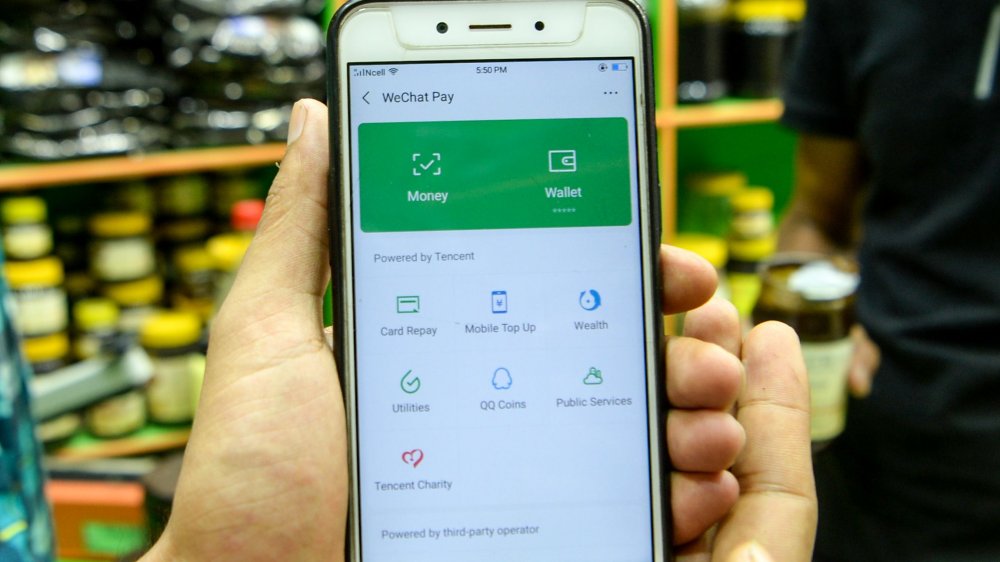

You need a WeChat account to do anything

Super apps are super common in China. In fact, one app in particular is so ubiquitous, so versatile, and so convenient that it's functionally impossible to live in China's cities or do any business at all in China without having an account on it.

WeChat was launched in 2011 by Tencent (the biggest video game company in the world and one of the world's largest and most valuable tech companies), and in addition to being a social media portal, WeChat is also a game console and a bank, and it's even used for ride-sharing, food delivery, and thrift shopping. You need a WeChat account on your phone to do anything in urban China. According to Business Insider, it's used to "message your friends, buy your groceries, hail a ride, and even book a doctor's appointment." In other words, if you want to live in China, you've gotta have it.

There some obstacles for WeChat's growth in the West, however. For example, users have to register their real name and phone number, and then there's the company's adherence to Chinese censorship and reporting practices. "I have to use it to communicate. I just have to know what's going on [in China]," Zhou Fengsuo, a Chinese-born human rights activist, told NPR. "But it is very dangerous. We have to use WeChat even though I know it's under surveillance all the time."

The college exams are driving students to suicide

Every spring, millions of Chinese high school students are busy preparing for their college exams. Almost 10 million Chinese students every year take a test that is basically their only chance to get into almost any of China's universities. Forget about SAT stress, China's National College Entrance Examination (aka gaokao, "the high exam") is known as the most feared test in the world. According to the Berkeley Political Review, "Schools may select just one in 500,000 applicants, and about 20 percent of students will not be accepted to any university at all." Worse still, when it comes to the best universities, only one percent make it inside.

Gaokao takers have actual police officers both escort them to the test, as well as search them when they arrive. During the test, there are drones flying overhead to catch cheaters. The test is so stressful that every year during the gaokao, Chinese social media and news is filled with stories of students committing suicide. These recurring tragedies have spurred some schools to install protective measures to prevent students from hurling themselves from the upper floors of their dorms and school buildings. The Guardian reported that a 2014 study revealed that gaokao stress "was a contributing factor in 93 percent" of student suicides.

As traumatic as gaokao can be, the system is seen by many as a keystone of China's egalitarianism. It sucks, but it sucks for everyone equally.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

You may be required to install a creepy tracking app

In addition to the tracking apps that Xinjiang's Muslims must have and the WeChat apps that are practically required for daily life in China's cities, the COVID-19 outbreak is forcing many tens of millions of Chinese to install an app that register the user's risk of catching the coronavirus. Depending on your political proclivities, this may not be inherently wrong or unwise. After all, governments around the world are already doing the same or considering similar approaches.

Already rolled out in over 200 cities in China, the system gives a simple color-schemed QR code, red-yellow-green, to demonstrate your risk potential. As a user on Weibo (China's version of Twitter) recounted, "When I told the landlord that I was coming back, he asked the first sentence: Are you green? Health code? No problem when it's green." The system still has some bugs though, as some users report members of the same household being issued different ratings.

Technically, there is no single coronavirus app. Instead, China's State Council instructed local governments and China's largest tech companies (Alibaba Group, Tencent Holdings, and Baidu Inc) to collaborate on the creation of multiple apps for each platform and region. Of course, that necessarily means sharing a lot of data with local authorities ... including the police, a situation which may be worrisome for civil liberties defenders.

In China, your business works for the government

You don't need to be a communist to own or operate a business in China. But the government does go out of its way to incentivize a cozy relationship between the state and business. For example, out of the 119 Chinese companies in the Fortune 500, 75 are state-owned enterprises. And the constitution of the Chinese Communist Party requires any business in China — to ensure doctrinal compliance, follow national strategy, and foster social stability through job creation — employing three or more Party members to form an executive Communist Party committee.

Foreign companies aren't exempt from this requirement, either. Zhang Lin, a Beijing-based economics reporter, wrote in the SCMP that "68 percent of China's non-state enterprises had set up Party cells by the end of 2016, and that 70 percent of foreign-funded firms in China had also done so." The extent of CCP interference is summed up in the China Business Review's advice for foreign companies, as it says, "While it is not always clear that the term 'private companies' incorporates foreign invested enterprises, this may be the most relevant guidance for foreign companies." In other words, just assume they'll make you do so eventually.

The Great Firewall of China

China has a long history of censorship, and Reporters Without Borders ranks the People's Republic at 177 out of 180 countries for press freedom. So perhaps it isn't surprising that the Chinese internet is heavily restricted. The world's most popular sites like Wikipedia, Facebook, YouTube, Google, WhatsApp, and literally hundreds of thousands of other websites are hidden behind the Great Firewall of China.

In spite of this, over 100 million Chinese people get on the global internet every year using a virtual private network (VPN) — software that hides your identity and enables you to connect to blocked sites. VPNs are of dubious legality in China, thus using one may lower your social credit score and may be worth a fine too. However, so many Chinese are accessing outside websites with VPNs or by being overseas that China has expanded its propaganda efforts to Western social media like YouTube.

The vast majority of Chinese actually couldn't care less about the Great Firewall, however. Indeed, for many it's just smart business sense. Block Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube so WeChat, Weibo, and Bilibili can grow. For many other Chinese, the Great Firewall is a valuable counter to what they see as an increasingly hostile world and censoring possibly destabilizing information is, again, just the smart thing to do in a country with hundreds of millions of people still living in poverty.

China has some really creepy facial recognition software

In China, there are more cell phones (+1.56 billion) than people (+1.42 billion), but that's in large part because many urban professionals report owning separate phones for work. It's near impossible to function in Chinese cities without the WeChat app, so it's practically required to have a phone.

So when the government began requiring in December that anyone registering a new SIM card for their phones or applying for new internet services must submit to a facial recognition scan, the news didn't make much of a stir. In fact, many welcomed it as a necessary preventative for rampant fraud. "As someone who has had their identity stolen, I feel relieved." said a typical post on Chinese social media, The Guardian reports. Said another Weibo post, "Even though this is coming too late, I support it."

There are concerns as to what this could do to China's already shrinking phone manufacturing industry, but others point out this will open other opportunities as the world's leader in facial recognition surveillance.