The Baseball Hall Of Fame's Biggest Controversies Ever

Baseball has been part of the American experience for more than a century. The sport is often used as a metaphorical stand-in for America itself, which makes sense. Just like the country that invented it, baseball has had its ups and downs, its scandals and investigations, and a steady evolution. And just like America, baseball has employed a bit of the old razzle-dazzle to promote itself, most notably with the Baseball Hall of Fame, established in 1936 (the physical Hall and museum were built a few years later).

Requiring 75 percent of the votes cast by members of the Baseball Writers Association of America (and players get booted off the ballots after ten years or if they receive less than 5 percent of the votes), the Hall is meant to enshrine only the greatest players of all time — men who embody the talent and sportsmanship championed by the game. Surprisingly, a game played for money (huge amounts of it in the modern era) doesn't necessarily attract the nicest or most morally upstanding people, and the Hall's voting procedure is weird and open to personal vendettas and crusades, resulting in plenty of controversial choices and decisions. Peel back the old-timey glamour of baseball as the pure All-American pastime, and you'll find plenty of dark, ugly stuff. From racism to cheating to steroids, here's the Baseball Hall of Fame's biggest controversies ever.

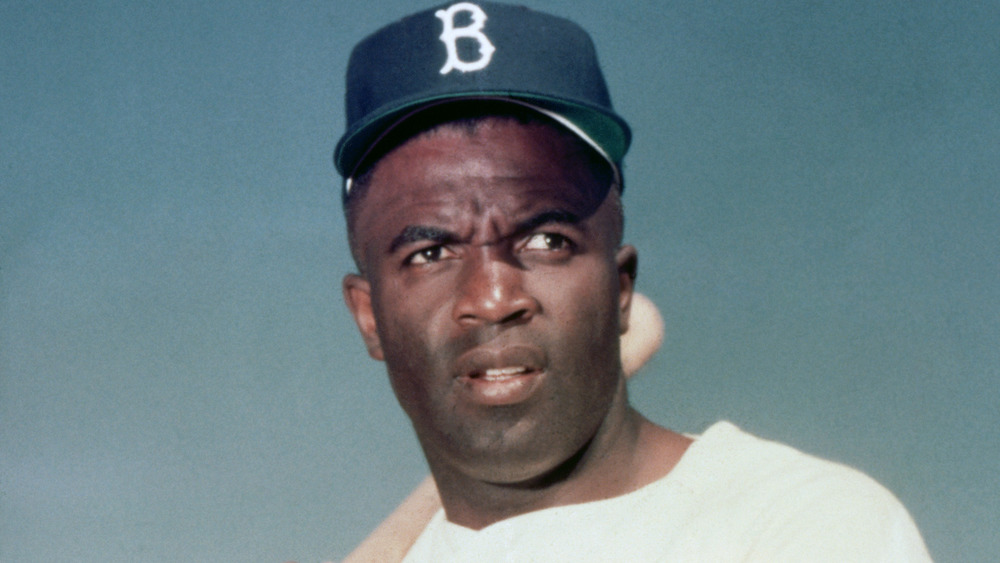

Jackie Robinson barely got into the Baseball Hall of Fame

To be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, a player has to appear on 75 percent of the ballots cast by members of the Baseball Writers Association of America. And you'd think getting that bare minimum would be easy for someone like Jackie Robinson, a man who was a legend in every way. After years playing brilliantly in the Negro Leagues, Robinson shattered the color barrier in Major League Baseball when he became its first black player in 1947, joining the Brooklyn Dodgers and being named Rookie of the Year.

Robinson went on to play brilliantly, winning a batting title and a Most Valuable Player Award before retiring. His MLB career was fairly short (just ten years) because he was already a 28-year-old veteran when he decided to endure years of abuse, death threats, and stress in order to take a stand against racism and break down a historic barrier. Despite the brevity of his playing career, he's credited with transforming the game, refocusing it on speed and on-base percentages instead of home runs.

And yet despite all of these achievements, when Robinson was elected to the Hall of Fame, he received just 77.5 percent of the votes. That means he made the cut by just four votes. A more blatant example of the lingering racism afflicting both the sport and the country can't be found.

Rogers Hornsby was probably in the KKK

You'd be hard-pressed to find a more revered figure in early baseball than the Rajah, Rogers Hornsby. Hornsby's stats are legendary. We're talking a .358 lifetime batting average, three seasons batting over .400 (including an incredible .424 in 1924), two Triple Crowns (leading the league in average, home runs, and RBI), and he's the only player in baseball history to hit over .400 with 40 home runs, a feat he managed in 1922. He later became a player-manager and was pretty successful in that role, too.

But Hornsby was never well-liked by his fellow players. In fact, as ESPN reports, when he was fired as manager of the Chicago Cubs in 1932 and the team went on to the World Series without him, the players voted to deny him a share of the bonus out of spite, and he was frequently fired and traded simply because he got along with precisely nobody. But worst of all, there are persistent rumors that Hornsby was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Author Charles C. Alexander writes that long-time sports reporter Fred Lieb maintained that Hornsby had admitted as much to him, and Hornsby was accused of releasing Catholic players from his teams because of his prejudices. Having Hornsby in the Hall remains controversial to this day.

Even though he was a terrible human being, Ty Cobb is still in the Baseball Hall of Fame

Ty Cobb was easily one of the most talented players in baseball history. He still holds the all-time career-best batting average (an incredible .366), and he batted over .400 three times, piling up more than 4,000 hits. So it's not too surprising that he was among the inaugural class inducted into the Hall of Fame, alongside Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson, Honus Wagner, and Christy Mathewson.

But Cobb was, by all accounts, a truly horrible human being and one of the dirtiest players in baseball. He was violent on and off the field. Smithsonian magazine notes multiple reports of Cobb assaulting people, and The New York Times recounts that one time, Cobb actually went into the stands to assault a fan. He was a documented racist, and ESPN reports that he bet on baseball games.

Despite this, Cobb remains in the Hall of Fame, and there isn't even any meaningful discussion about reviewing whether or not his deplorable actions should lead to a reconsideration. Meanwhile, other players, who committed just one of the many offenses Cobb piled up (while getting more hits) are banned.

The PED era has majorly affected the Baseball Hall of Fame

What's become known as the "performance-enhancing drug (PED) era" in baseball — roughly dated from the late 1980s through the early 2000s — is a scandal that continues to reverberate throughout the sport. No one knows exactly how many players were guilty of taking both legal-at-the-time and never-legal drugs to gain an edge, but it was a lot of them, and the inflated statistics of the era are clear evidence that there was essentially wholesale cheating going on in the sport.

This has now infected the Hall of Fame voting as players widely suspected of using PEDs become eligible. The writers who vote on Hall of Fame inductees aren't beholden to any clear rules or guidelines, so they can — and do — leave players off their ballots for personal reasons, and many resent players they suspect used PEDs. As Deadspin notes, Mike Piazza, one of the most dominant catchers of his time, was widely suspected of steroid use, which almost certainly explains the fact that he failed to get the required 75 percent of the vote the first three years he was eligible.

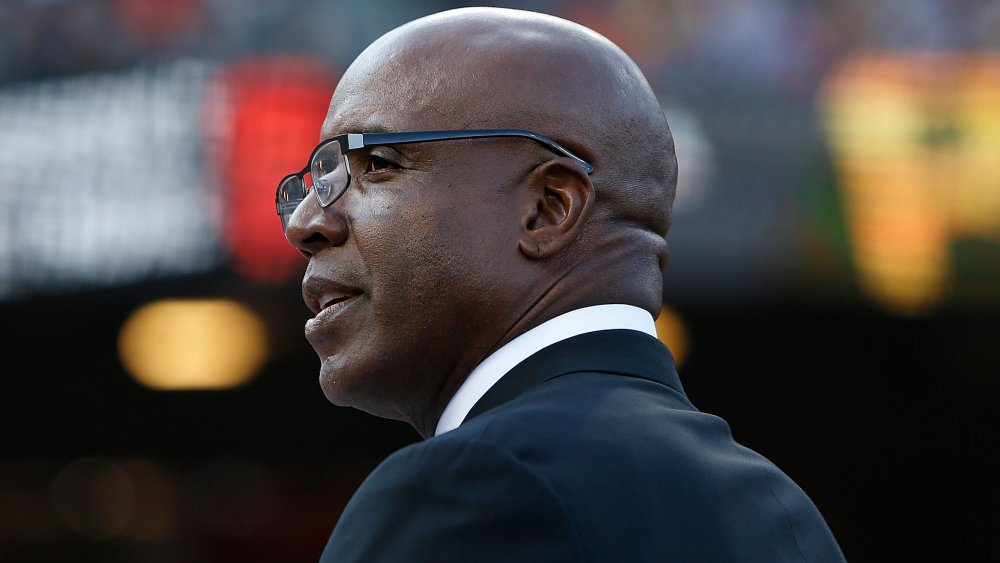

Also, players like Barry Bonds, who holds both the single-season (73) and all-time (762) home run records, or Roger Clemens, who has 354 wins and seven Cy Young Awards, aren't in the Hall because they're suspected of using PEDs. Meanwhile, as The Hardball Times reminds us, legendary Braves manager Bobby Cox literally beat up his wife, and yet he's happily ensconced in the Hall.

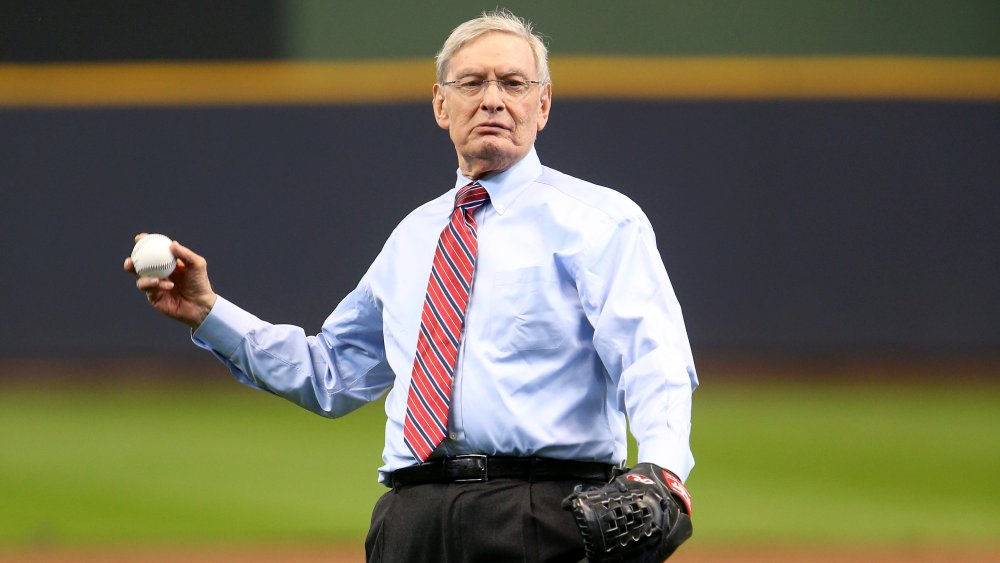

Bud Selig oversaw a controversial period in baseball's history

The role of commissioner of baseball isn't what it used to be. Originally created in the wake of the Black Sox cheating scandal of 1919, the office was intended to rebuild confidence in the game, as well as save the league from the inter-team squabbling that threatened to tear it apart. In the modern day, the commissioner is much less independent than originally conceived, but the position is still plenty influential, as Bud Selig proves.

Selig, who served from 1992 until 2015 (the first several years, he was officially an "acting" commissioner), oversaw the disastrous 1994 strike that saw baseball's popularity nosedive. He also oversaw the exciting home run competition between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa in 1998, credited with re-sparking fans' love of the game and rehabilitating its image. The problem is that McGwire and Sosa — and many other players — were both almost certainly using performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) at this time, and as Fox Sports notes, Selig didn't take the problem very seriously until years later. He didn't institute a strong drug screening policy until 2005, which means he basically allowed the so-called PEDs era of baseball to flourish, probably because it was good for business ... until it wasn't. And yet Selig is in the Hall of Fame despite these failings.

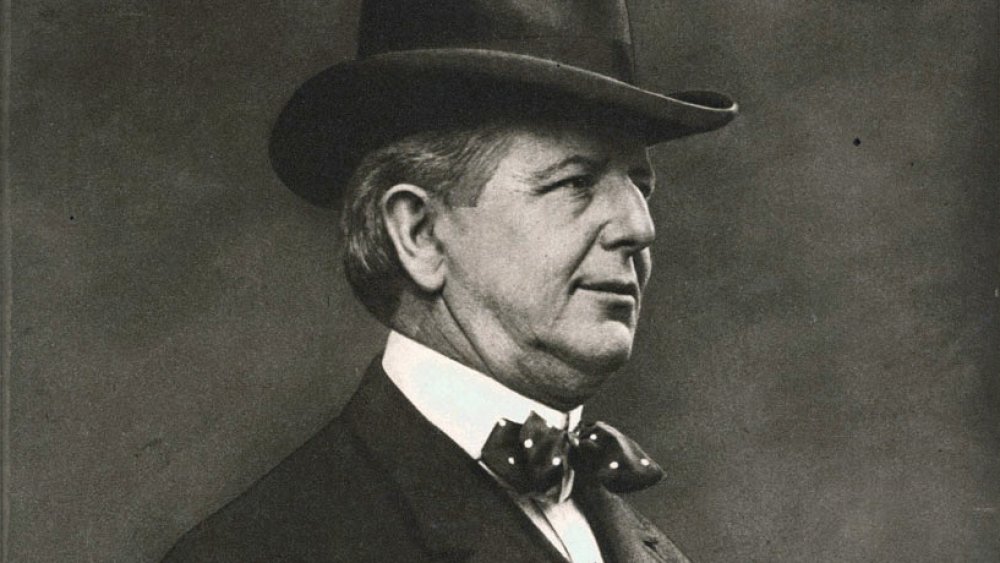

Cap Anson helped segregate baseball

Most people think they know the story of race and baseball. The sport was segregated from its inception until Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey broke the color barrier in 1947. But the fact is baseball wasn't always a segregated sport. In the 19th century, while there were racist and segregationist forces in the game, it wasn't uncommon for teams to have black players.

Who knows what might have happened if Hall of Famer Cap Anson hadn't been around.

One of the most legendary 19th-century players, Anson was elected to the Hall in 1939 ... and as The Washington Post reports, he was instrumental in ensuring that baseball closed its ranks to black players. Anson was a superstar, and when he vocally refused to play against teams that employed black players, teams were forced to give in. This in turn made it easier for other racists to do the same, and by the 1890s, there were no black players in professional baseball, largely due to Cap Anson's efforts.

Granted, the Hall does acknowledge Anson's history but only barely. There's a paragraph buried deep in his official biography, but overall, the bio mostly focuses on his hitting prowess and supposed reputation as embodying everything that's great about baseball.

Whitey Ford is still in the Baseball Hall of Fame even though he's confessed to cheating

In the 1950s, the New York Yankees were a force of nature. They finished in first place every year but one from 1949 to 1958 (finishing second in 1954 despite winning 103 games). Whitey Ford was a big reason for that success, racking up 236 career wins over 16 years with the Yanks, a career that got him into the Hall of Fame in 1974.

The controversy over Ford's election to the Hall centers on cheating. Ford admitted several times that he cheated and pretty blatantly, too. As ESPN reports, Ford used several techniques. For example, he would cut the ball with his ring. Sometimes, he would load the ball with mud that he purposefully seeded around the pitcher's mound, or he'd use a special "gunk" he prepared ahead of time. Ford made it clear that as he aged into his 30s, he lost some of his athletic abilities and was forced to resort to cheating in order to stay competitive. In one late 1980s interview with The New York Times, in fact, Ford said he approved of pitchers cheating because the money was too good to pass up.

The end result is that a player who not only admits to cheating but even endorses cheating has a plaque in the Hall of Fame. Seriously, the man has received baseball's highest honor even though you have to question some of those late-career wins on his record, including his post-season wins, since Ford said of the 1963 World Series against the Dodgers, "I used enough mud to build a dam."

Larry Walker and his Coors Field-inflated offensive stats

The 2020 Hall of Fame class consisted of Derek Jeter, who got 99.7 percent of the votes, and ... Larry Walker. Walker was a good player, ending his career with a .313 batting average and 383 home runs, plus three batting titles in which he batted .363, .379, and .350, all very impressive numbers. So what's the problem? Well, Walker's numbers are a little on the weak side for the Hall, and he got a boost from Coors Field, a stadium that's notorious for boosting hitting numbers (and ruining pitching numbers).

As Forbes reports, Coors Field is "by far the most hitter-friendly yard in the game," and Walker undoubtedly got a boost from it. Prior to joining the Colorado Rockies, Walker's career batting average was .282 — a perfectly respectable number but nothing compared to the .334 he hit as a Rocky. While there are other ways of judging a player's impact, it's pretty clear that Walker benefited from a serious home field advantage. And sure, he didn't play poorly on the road, just not as spectacularly.

This is one reason it took Walker so long to get into the Hall (2020 was his final year of eligibility). In 2014, he received just 10.2 percent of the votes, largely because of the Coors Field stigma. Fans continue to argue both sides of the Coors Field drama, but until the Hall of Fame explains how stats like Walker's magically go from not good enough to just barely good enough, the Hall has a credibility problem.

The Veterans/Eras Committee has a race problem

The Eras Committee, also known as the Veterans Committee, is charged with reviewing the careers of players who failed to be elected to the baseball Hall of Fame during their initial eligibility. Recent years have seen changes that have shifted the focus to more modern players, but the idea is the same: Give some deserving players a second chance. However, there's one problem. As The Sporting News noted in 2017, the Veterans Committee "has never enshrined an African-American who played his entire career in the major leagues." In other words, the black players the Veterans Committee has enshrined all played some of their time in the Negro Leagues.

While this is arguably due to the noticeable lack of black players prior to 1947 (and until 2016, one of the committees under the Eras umbrella could only consider major league players prior to 1947 — who were, of course, all white), plenty of big names haven't made the cut. There's Dick Allen, Vida Blue, and Maury Wills, to name just a few. Recent changes to the committee structures have improved things, but even if players like Blue (who's 70) and Wills (who's 87) are eventually recognized as the greats they were, it might be too late for them to enjoy the honor while they're alive.

Charles Comiskey doesn't belong in the Baseball Hall of Fame

The Black Sox scandal of 1919 remains a seminal moment in baseball's history. Eight players for the Chicago White Sox were accused of taking bribes to throw the World Series. All eight were banned from baseball (despite never actually being convicted of the crimes), and baseball brought in a tough commissioner (Kenesaw Mountain Landis) to oversee the game. However, there's one man who never suffered despite his obvious role in the scandal — Hall of Fame owner Charles Comiskey.

As Fox Sports notes, Comiskey was a criminally mean-spirited boss who underpaid his players — in the pre-free agency era, the athletes had little leverage or recourse — and treated them pretty badly. Aside from humiliation, like making them launder their own uniforms, he often cheated by benching players in order to prevent them from getting contractual bonuses. For example, it's said that when Eddie Cicotte was within one win of triggering a $10,000 contractual bonus, Comiskey ordered him benched. Comiskey was also a big fan of racial segregation in baseball. But despite Comiskey's treatment of his players, the scandal, and his obvious negative influence on the game, Comiskey gets a plaque in the Hall.

What's Harold Baines doing here?

One of the most controversial aspects of the Hall of Fame is the Eras Committee, also known as the Veterans Committee. The committee is designed to reconsider players who failed to make the vote during their ten or 15 years of eligibility (depending on when they retired). This makes sense for players who have borderline statistics or other reasons they might've been overlooked, but the Eras Committee too often elects players who obviously fall short.

This was highlighted in 2018 when Harold Baines was elected (along with Lee Smith) by the Eras Committee. While Smith arguably has the stats for inclusion (his 478 saves rank third all-time), Baines never got more than 6.1 percent of the votes during his initial eligibility ... and for good reason. Baines was a good player, certainly, and his 2,866 hits looks pretty impressive at first glance. But Baines' main achievement as a player was longevity. Despite being frequently injured and not much of a defensive player, he played for 22 years. As Sports Illustrated put it, "There's nothing to Baines' Hall of Fame case beyond his prodigious hit total, and he got there by piling up thousands of plate appearances as a plodding DH who could barely play the field." Even Baines admitted to being "very shocked" when he was inducted.