The Untold Truth Of Apollo 13

In the spring of 1970, NASA prepared for its Apollo 13 mission, with astronauts Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise set to become the third crew to walk on the Moon. But this was intended to be more than just a moonwalk: The Apollo 13 crew's ultimate purpose was to learn more about the Moon's largely mysterious Fra Mauro formation, including surveying, rock sampling, and deploying a surface experiments package. Beyond its scientific pursuits, the mission, launched on April 11, 1970, also sought to enhance human capabilities in the lunar environment, laying the groundwork for future explorations.

Despite achieving what had seemed impossible just 10 years earlier, public interest in lunar missions had dipped after the success of Apollo 11. The public's gaze shifted downward, grappling with more pressing concerns closer to home, and questioned the unreasonably high cost of space exploration. All this changed, at least for a while, when Apollo 13 turned into a nail-biting rescue mission.

Even though Apollo 13 failed to achieve its original goals, the world became enthralled with the story of this "successful failure": its story, its legacy, and how it narrowly avoided tragedy. And even after all this unexpected attention, more was happening behind the scenes than you might know.

No one cared about the mission — but everyone cared about the rescue

Imagine a space mission being met with a collective global yawn; that's the reality Apollo 13 faced in 1970. TV networks didn't even bother broadcasting a live interview with the astronauts during their mission, an event that one would expect to be a massive draw for audiences.

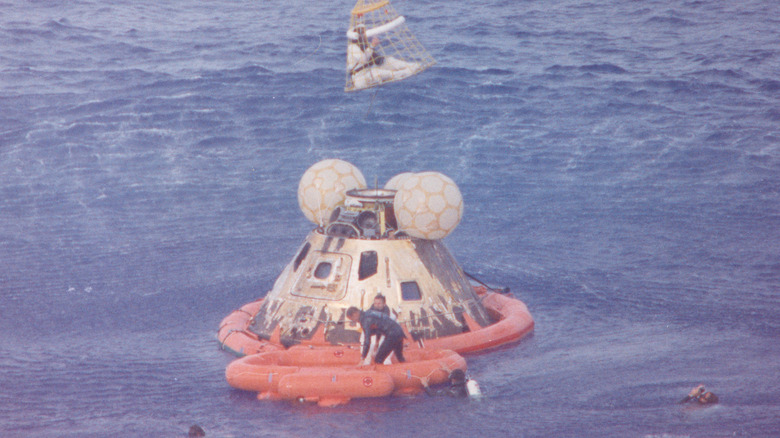

But when the seemingly routine mission turned into a desperate fight for survival, the world suddenly held its breath. For four nail-biting days, the plight of the Apollo 13 crew became a global obsession. The lunar module Aquarius became the Apollo 13 crew's lifeboat, providing oxygen and a backup engine. Meanwhile, astronauts and engineers at NASA worked feverishly, improvising solutions to keep the imperiled crew alive and help them bring their hibernating command module back to life. Finally, on April 17, they splashed down safely in the Pacific, greeted by a waiting public.

Tens of millions of Americans witnessed the event, with live coverage spanning from Houston Control to the retrieval operations miles away. This global audience likely swelled further, surpassing any potential viewership of a successful moon landing (and arguably uniting the world more profoundly than even the first Apollo landing). This was largely due to NASA's communications approach, honed from experience; aside from providing honest and timely updates, the agency also gave the media direct, up-to-date access to the transmissions between Mission Control and the Apollo 13 crew.

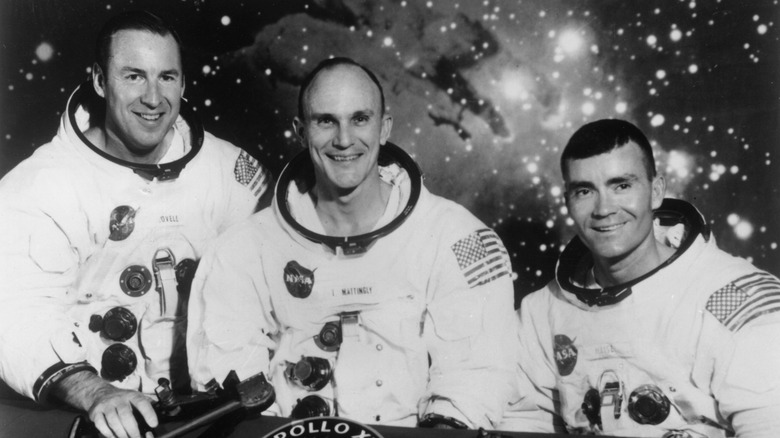

One of the crew members was a last-minute replacement

Bound by experience, resilience, and a dash of quick thinking, the Apollo 13 crew — Commander James "Jim" Lovell, lunar module pilot Fred Haise, and command module pilot John "Jack" Swigert – would face challenges unlike any they could have imagined. But had it not been for an unexpected illness, the final roster would have looked slightly different.

Lovell, a veteran of two voyages, helmed Apollo 13; his steady hand and wealth of experience were vital for the journey ahead. Joining him was Haise, eager to leave his bootprint after years of training and anticipation. But a last-minute swap scrambled the roster. Just 48 hours before launch, Ken Mattingly, the originally planned pilot (pictured above, center), was exposed to German measles (a disease for which he had no immunity) via a member of the backup crew. Stepping in on short notice was Swigert, a rising star known for his cool head and quick thinking under pressure.

Speaking with Universe Today, NASA engineer Jerry Woodfill shared his opinion that this last-minute swap contributed to the crew's successful rescue. For starters, Swigert's mental and physical conditioning as a former collegiate athlete likely made him better suited for the situation than the less brawny Mattingly. Moreover, Swigert was reportedly the one astronaut in the Apollo program who was best equipped for command module troubleshooting. Or, as Woodfill put it, "[Swigert] was the most conversant astronaut for any malfunction that occurred in the CSM."

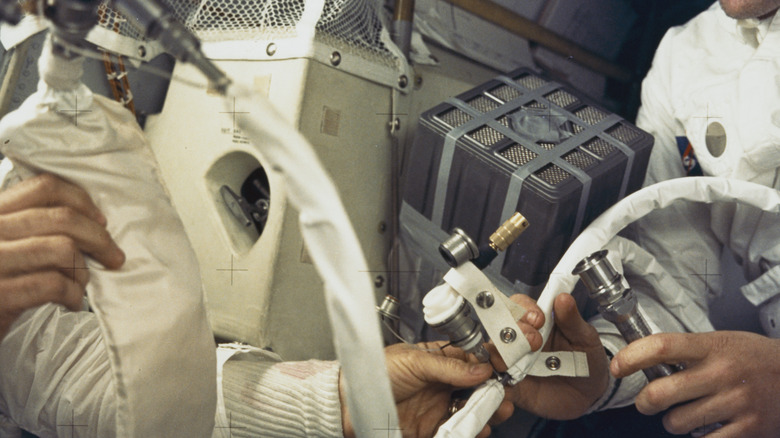

A stroke of last-minute DIY creativity helped save the team

When catastrophe struck the three-man Apollo 13 crew, they squeezed into their lunar module, which was designed only for a cozy duo. But there was another hitch: the lunar module's carbon dioxide filters were seriously inadequate for three pairs of lungs.

Back on the ground, the minds at Mission Control huddled, conjuring a fix using the most MacGyver-esque materials imaginable. Plastic bags, cardboard, a spacesuit hose, and even duct tape all became players in this cosmic tinkering session. The result: A makeshift filter dubbed the "mailbox," due to its crude resemblance to an ordinary mailbox. Huddled in the cramped module, Lovell, Swigert, and Haise recreated their makeshift lifeline based on Mission Control's meticulous instructions. To everyone's relief, the lunar module "mailbox" hummed to life. This bought the astronauts precious hours, keeping the air breathable and their hope alive.

"The beauty in this whole thing was, [the people at Mission Control] were so prepared for even the most implausible things," astronaut Ken Mattingly, who was supposed to fly on Apollo 13, explained to Popular Science. "They knew no one had ever simulated exactly what happened, but they had simulated the kind of stress that could be applied to the system and the people in it. They knew what their options were, and had some ideas already in place about where to go."

The Apollo 13 mission holds an impressive, albeit incidental, world record

While scrambling to survive after the explosion impaired their spacecraft, the crew of Apollo 13 needed to get back home, and fast. To do this, they had to slingshot around the moon on a trajectory vastly different from any Apollo mission before. This unplanned celestial waltz led them to obtain an unexpected and unplanned distinction: traveling the furthest distance that humans have ever traveled away from Earth. Per the Guinness World Records, Apollo 13 zoomed past about 254 kilometers (158 miles) from the farthest point of the Moon (apocynthion) and approximately 400,171 kilometers (248,655 miles) from our blue marble. This record, written in the stars nearly 54 years ago, remains unchallenged to this day.

Even more fascinating is the fact that the Moon itself played a key role in humanity's longest jaunt. During Apollo 13's perilous journey, the moon happened to be hanging out near its apogee, or the farthest point in its elliptical orbit around Earth. This cosmic coincidence nudged the spacecraft even further outward, adding about 60 miles to its record-breaking distance. But while the Moon's influence was a bonus, everything ultimately boiled down to the unique slingshot maneuver necessitated by the emergency. Apollo 13's free return trajectory, designed to slingshot around the Moon and slingshot back towards Earth with minimal fuel expenditure, took them around the dark side of the Moon, contributing to their distance record.

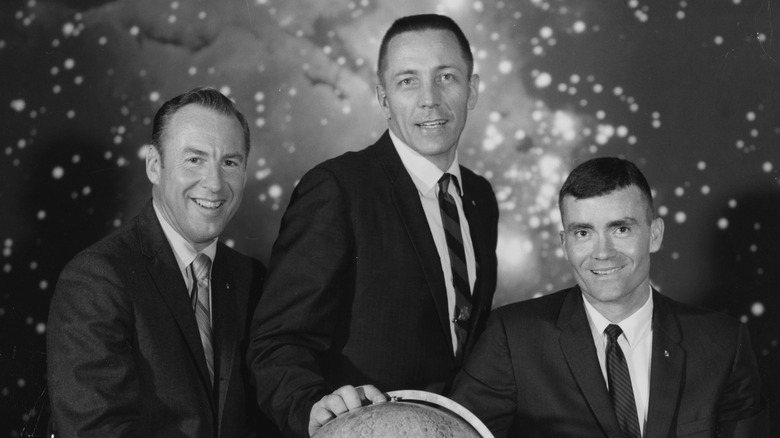

Even though the crew survived, none of them ever returned to space

Though the Apollo 13 crew touched down safely, their perilous journey back to Earth certainly took its toll, in more ways than one. For starters, the crew's health suffered: All three experienced drastic weight loss and dehydration (per NASA). Fred Haise even developed a urinary tract illness while in the cramped confines of their spacecraft. As James Lovell shared with Astronomy: "[Haise] got an infection, a bladder infection. He got the chills and things like that. I tried to keep him warm. Every once in a while, I'd give him a bear hug and try to heat him with my body. But he hung in there, fortunately."

In the end, none of the Apollo 13 crew ever explored space again. Lovell embraced new horizons in the business world. He landed the role of president at Fisk Telephone Systems, Inc., and continued to climb the corporate ladder until his retirement in 1991. Haise left NASA in 1979, joining Grumman Aerospace Corp. as its vice president of space programs and eventually retiring in Texas.

As for Jack Swigert (pictured above, center), he entered the political arena and campaigned for a seat in the U.S. Senate, only to have his time cruelly cut short. After overcoming a cancerous tumor, he faced another health challenge: lymphoma. He died of pneumonia on December 27, 1982, just one week shy of taking his seat in Congress at the age of 51.

Houston, we have a problem ... with being misquoted

As far as space-themed movies go, there's one quote that undeniably echoes through cinematic history: "Houston, we have a problem." This iconic phrase from the 1995 film "Apollo 13," uttered by Commander Jim Lovell (Tom Hanks), has been forever linked to the Apollo 13 incident, painting a picture of calmness in the face of a crisis. But while often cited in various media, this cultural cornerstone turns out to be somewhat inaccurate. It was actually Jack Swigert, not Lovell, who first broke the news. His words, though tense, carried a nuance often lost: "Okay, Houston, we've had a problem here." This "had" past tense hinted at a developing situation rather than a sudden catastrophe. He even repeated his statement, prompted by Mission Control to "say [it] again" for clarity.

As to how the film still managed to get it wrong: The misquotation's origins seem intertwined with both Hollywood and cultural influence. The filmmakers reportedly used the shortened quote for dramatic effect; it resonated with audiences, solidifying its place in popular culture. There's also the fact that NASA named their 1983 radio program "Houston, We Have a Problem," which may have inadvertently contributed to the confusion.

Curiously, this wasn't even the first time Hollywood botched the quote. Another version of the phrase predates the 1993 film: the 1974 TV drama film "Houston, We've Got A Problem," a production that Lovell reportedly despised as a whole for its inaccuracy.

Repeated attempts to fix a malfunctioning hatch almost doomed the Apollo 13 crew

Sudden loud noises are never a pleasant experience, wherever you are. And when you're inside a metal can in space, they can signal a potentially deadly situation. Jim Lovell described the sound that the Apollo 13 crew heard as a "bang-whump-shudder," which led the Apollo 13 commander to assume the worst: A possible collision with space debris that could bring about depressurization (and horribly grisly deaths for the crew onboard). To prevent this, he ordered Jack Swigert to seal the hatch between the command module Odyssey and the lunar module Aquarius. Yet, despite five desperate attempts by both Swigert and Lovell, the hatch stubbornly remained open.

Being unable to close the malfunctioning hatch forced the crew to stop trying and focus their attention elsewhere. This seemingly minor change, born out of frustration and a hatch that just won't budge, bought them the precious minutes necessary for them to realize the true culprit: not a cabin leak, but a ruptured oxygen tank in the command module. Had the hatch cooperated, their attention might have remained fixated on it, delaying the discovery that saved their lives.

But if the hatch wasn't really the problem, then why didn't it close? NASA Engineer Jerry Woodfill shared his thoughts on the possible reasons with Universe Today: "One man believed the inability to make the hatch close resulted from differential pressure between the vehicles ... The misalignment in the hurried closing was responsible."

[Featured image by Steve Jurvetson via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

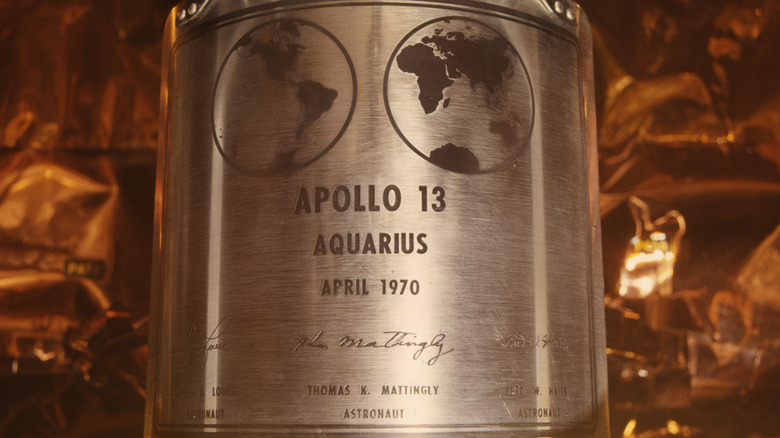

The lunar module manufacturers sent an invoice for towing services as a joke

After what was left of the handicapped Apollo 13 spacecraft limped back to Earth, it touched down in the ocean, taking its crew a step closer to a successful rescue. But amidst the relief and praise, a lighthearted jab emerged from the ashes of near-tragedy: the "towing bill" from Grumman, the lunar module's makers, to North American Rockwell, the builders of the faulty service module.

Test pilot Sam Greenberg, with a touch of humor, created the invoice at Bethpage, Long Island, in between sessions of his Apollo 13 lunar module simulations. It demanded exactly $312,421.24 for "towing services" rendered, with mock charges like "four dollars per mile, one dollar per additional mile," and even a line for "jumper cable usage during re-entry," per an image uploaded by Heritage Auctions.

Upon receiving the invoice, North American Rockwell had its Houston auditor review it, and, as reported by The New York Times, Earl Blount, the public relations director of its California space division, subsequently delivered a statement. Blount dryly yet jokingly pointed out that Grumman should consider unpaid invoices for previous lunar module transport services. This tongue-in-cheek gesture acknowledged the lunar module's unexpected and critical role in saving the crew after the service module malfunctioned. While it was never truly intended for such extensive use, the module's power reserves and capabilities proved extremely vital in the crew's successful return.

The Apollo 13 mission was the catalyst for an important spacesuit redesign

While the Apollo 13 crew's lunar dreams remained unfulfilled, the mission did pioneer a small yet significant change in astronaut attire for future missions: There were crimson stripes wrapped around the arms and legs of Commander Jim Lovell's suit (pictured above). These weren't merely aesthetic flourishes; they were visual flags to instantly identify the commander of a given space mission.

NASA explains the story behind this design choice, the seeds of which were planted during the Apollo 11 mission. The agency's public affairs division was under pressure from the media to provide "the best shot" (or even "any shot") of Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the Moon. But the team had a tough time identifying Armstrong in their films, prompting them to implement an astronaut identification method for succeeding Apollo missions. As British researcher Keith Wilson remarked, "It was Brian Duff who was partly responsible for the inclusion of stripes on the CDR's spacesuit on later missions – too late for Apollo 12. For 24 hours, they were called the 'Public Affairs Stripes' before being renamed the 'Commander's Stripes'."

Apollo 14, the mission that followed, embraced the fiery markings, sending Alan Shepard onto the lunar surface adorned with the commander's stripes. These stripes became a fixture in Moon mission fashion, adorning every commander's suit thereafter.

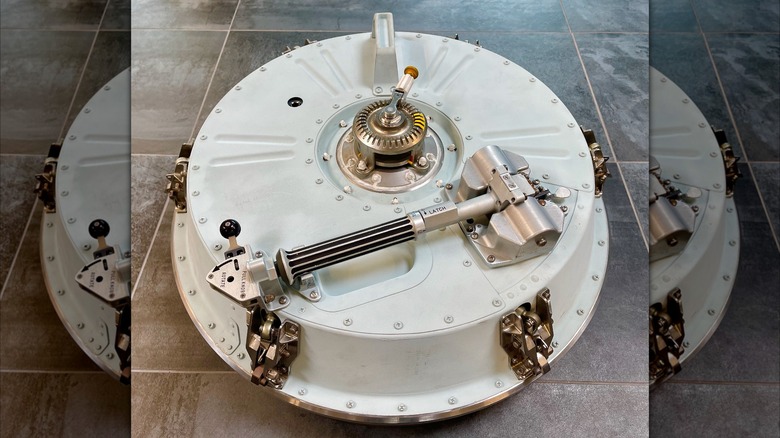

The Apollo 13 mission prompted NASA to make major changes to the Apollo modules

Following the safe return of Apollo 13's crew, NASA conducted an investigation into what went wrong with the mission, obtaining valuable data that could help them prevent future mission catastrophes. As a result, a series of critical design changes reshaped the modules, making them safer, sturdier, and better equipped to face the unforgiving vastness of space.

In a Reddit interview (via the Smithsonian), National Air and Space Museum curator Teasel Muir-Harmony said, "After an investigation into the Apollo 13 accident, NASA modified the spacecraft electrical system significantly for the next Apollo mission ... It's worth mentioning that NASA improved and updated hardware throughout the Apollo program, learning from each mission."

One of the most crucial additions was a third, isolated cryo oxygen tank as a precautionary measure for possible system failure. Additionally, vulnerable fans and wiring within the tanks were removed to minimize potential sources of sparks capable of triggering another explosion. Thermostats, once seen as fail-safes, were suddenly deemed too risky. Their replacement with simpler, more reliable temperature gauges offered a clearer picture, empowering astronauts with instant, actionable information in the face of overheating. The space module was also equipped with a beefed-up 400-amp-hour lunar module battery, addressing the need for more power. Meanwhile, extra storage bags for water found their way into the command module, reducing the risk of future crew members becoming dehydrated.

A 1969 movie may have helped save the Apollo 13 crew

During Apollo 13's escalating troubles, an electrical engineer at NASA, Art Campos, remembered a line from a film he had recently seen, which featured a similar space-themed crisis. It was this memory that ultimately enabled the Apollo 13 astronauts to revive their command module's batteries, making it possible for them to return to Earth.

Talking with Universe Today, NASA engineer Jerry Woodfill shared his account of how his colleague Campos came up with the idea, saying, "As Art was driving to Building 45 at the Manned Spacecraft Center, he recalled the movie, where they said 'charge the batteries' and then remembered a procedure he devised about a year earlier, a way to charge depleted emergency batteries by using a jumper charge between the two vehicles. I really think "Marooned" was the catalyst for Art remembering this wire." Despite the fact that the Earth-bound rescue team's frantic simulations showed that this fix wouldn't work, the Apollo 13 crew tried it anyway — fortunately, with positive results.

Released just months before the Apollo 13 launch, "Marooned" tells the fictional tale of three astronauts stranded in space, forced to use their lander's batteries to power their damaged modules. The similarities were eerily uncanny. For starters, in both the film and the Apollo 13 incident, a spacecraft relied on makeshift power solutions while crews faced life-or-death decisions. Moreover, both "Marooned" and the Apollo 13 mission were led by a commander named Jim.