The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Sitting Bull

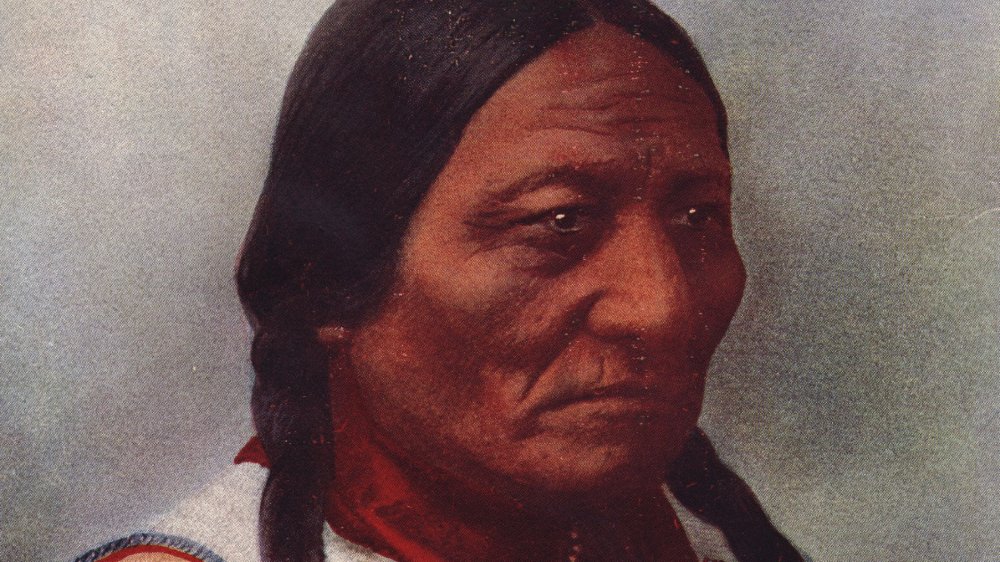

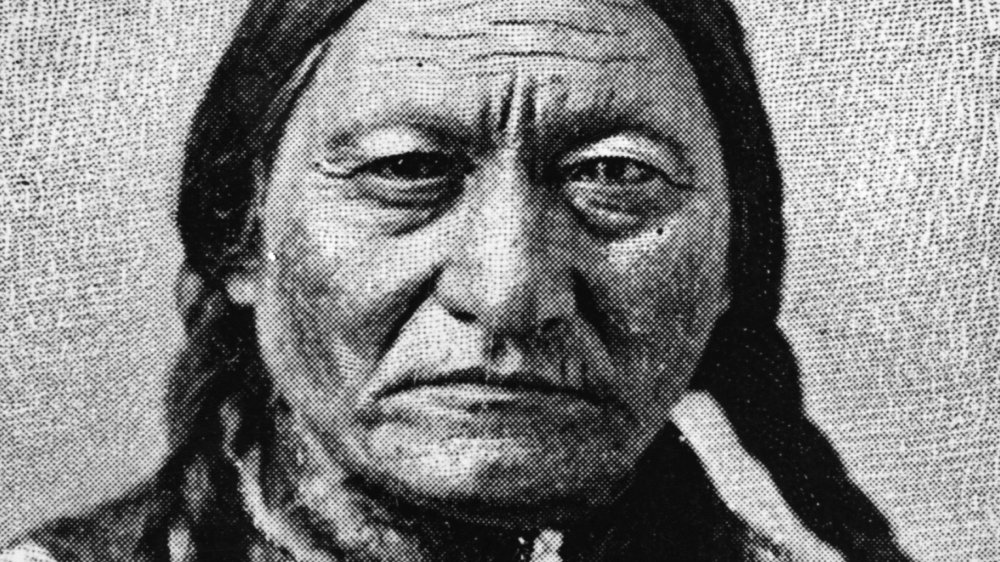

Sitting Bull is one of the most famous Native Americans in history. His name is just as recognizable as that of his American cavalry counterpart, Lieutenant Colonel George Custer. Where Custer led troops with the purpose of removing the indigenous population from their lands, Sitting Bull became their symbol of resistance.

Sitting Bull was more than just a rebel icon, not that you'd be able to tell from the way this courageous leader has been wrongly portrayed in most films for the past 100 years or so. He was both a spiritual and tribal leader of the Hunkpapa, a band of the Lakota tribe and part of the Great Sioux Nation that roamed the Great Plains freely before the Westward Expansion. According to Access Genealogy, it was under Sitting Bull's leadership that the Hunkpapa became one of the last bands of Sioux to submit to relocation.

This tribal leader had amassed his fair share of glory. During his relentless struggle against the colonizers who sought to see his people forced from their ancestral lands, he displayed almost superhuman courage in several famous battles. But this legacy of bravery is only part of the story. The lens of history has a way of turning humans into legends while ignoring the tragedy of their lives. Sitting Bull was certainly a man worthy of legend, but his tragedy holds lessons we should never forget.

Sitting Bull's people were attacked during a war in which they took no part

Sitting Bull wasn't always this great leader's name. According to History, he'd go through a series of names, including "Jumping Badger" and "Slow." Though "Slow" sounds like an insult, it was actually a testament to Sitting Bull's deliberate nature. Slow, who took down his first buffalo at the age of 10, would go on to earn his father's name, Tatanka-Iyotanka or "Sitting Bull," after joining his first raiding party at 14. While at this point he was using the name he'd keep for the rest of his life, he still hadn't had his first encounter with American soldiers.

The young warrior would meet the United States Army for the first time in 1863, according to PBS: New Perspectives on the West. The military was attacking several Sioux camps in a retaliation effort for the Santee Rebellion, whether or not they had actually been involved in said rebellion. The Hunkpapa was one of the uninvolved bands attacked.

A year later, the man leading the campaign into the Dakotas, Brigadier General Alfred Sully, would attack a village of 8,000 Sioux that included Sitting Bull in 1864. The Sioux had captured Fanny Kelly, a white American woman, and the U.S. wasn't happy about it. The attack was brutal and much of the Sioux was forced to retreat to the Badlands while leaving the majority of their possessions behind, according to the National Park Service.

Sitting Bull and the Great Sioux War of 1876

The Great Sioux War of 1876 was one of the most devastating of the First Nations Wars. In all, the war was fought across 27 battlefields in five different states. It cost millions of dollars, even in 1876 money. According to the University of Oklahoma Press, almost one-third of the army fought the Sioux and the Northern Cheyenne for nearly two years. Where was Sitting Bull in this?

Well, gold was found in "them there" hills. The Black Hills to be exact. And, there was no way the United States was going to let the native people sit on a pile of wealth. So, they booted the Sioux from their reservation. This was holy land to the Sioux, according to Cultural Survival, but the government at the time gave no care to extend religious freedoms to people who weren't white or Christian. Britannica says the new location Sitting Bull and his people were being forcibly relocated to was over 240 miles away and the order to move their whole existence came near the end of 1875. You know, winter. Even if Sitting Bull wanted to relocate his village, he wouldn't have been able to do so by the January 31 deadline, and his people would've died from the bitter cold had he tried.

There was a time in the great headman's life where he tried to trade and make peace with white Americans, but that was no longer in the cards.

Sitting Bull's victory at the Battle of Little Bighorn

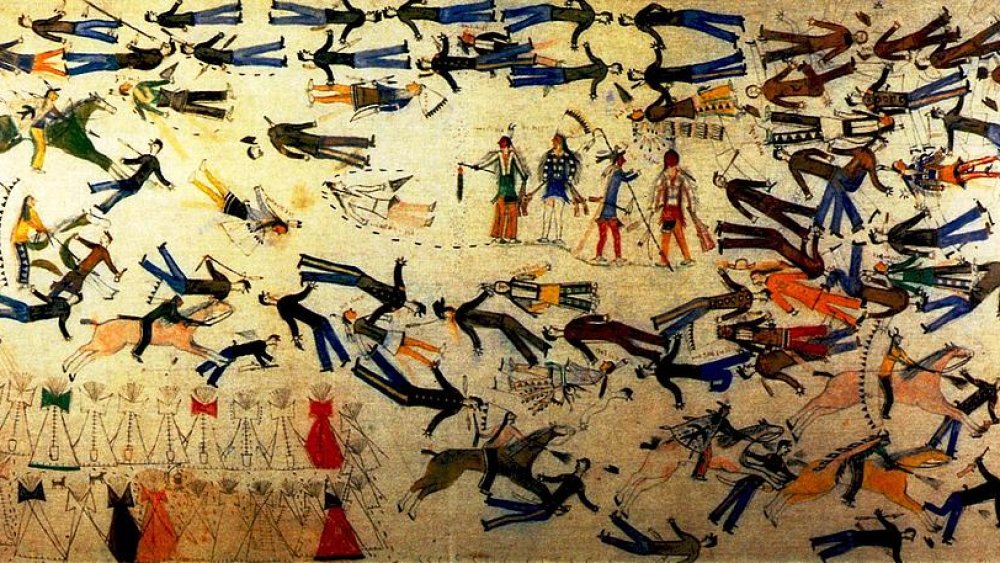

It was March of 1876, amidst the Great Sioux War when Sitting Bull called the Lakota, the Cheyenne, and the Arapaho together. At his camp in Rose Bud Creek, he led the tribes in a Sun Dance ritual. The ritual entailed that he slash himself a hundred times in sacrifice to the Great Spirit, according to PBS: New Perspectives on the West. A vision came to Sitting Bull during this ritual. Soldiers fell from the sky like grasshoppers.

The omen set Crazy Horse, the Ogala war chief, into action. He led his warriors to the Battle of the Rosebud and surprised the U.S. soldiers, leading to a concise victory. To celebrate, Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull moved the Lakota camp to Little Bighorn where they were met by more than 3,000 additional Sioux and Cheyenne.

According to History, the camp along the Little Bighorn river had more than 10,000 people when Lieutenant Colonel George Custer and the 7th U.S. Cavalry attacked. The soldiers arrived only to be met by a much larger force rallied by Sitting Bull, who's old age kept him protecting the women and children away from the thick of the battle. Custer should have listened to his scouts when they reported the size of the Sioux force. Instead, his 215 troops got wiped out by 3,000 braves, with 400 additional troops barely managing to defend themselves. This was one of two battles lost by the U.S. Army, and they wouldn't take it lightly.

Four years in exile

Following their victory at the Battle of Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull and the Sioux feared the U.S. military would retaliate in a big way, so they decided to split their numbers into smaller bands. History says many of these bands were tracked down and forced to surrender and take their place on reservations. But, Sitting Bull's band was never captured, spending the next two seasons hunting buffalo in the Montana territory and avoiding major confrontations with U.S. forces.

Sitting Bull met with Colonel Nelson A. Miles in the fall of 1876. Miles tried to talk the Little Bighorn victor into surrender but Sitting Bull refused. This didn't bode well with Miles. Angered at Sitting Bull's justified refusal, Miles doubled down on harassing his people. Between the harassment and the growing scarcity of buffalo, Sitting Bull had little choice but to leave his homeland and lead his people to Canada.

At first, the buffalo was more plentiful north of the border, where Sitting Bull and his people stayed for four years. During their time in "Grandmother's Country," the buffalo herds were hunted by the indigenous people, settlers, and those looking to sell hides. Food was growing scarce once again. Though he refused a pardon initially, the threat of starvation and increasing pressure from the Canadian Mounties was eventually enough for Sitting Bull to lead his people back home.

The great chief is imprisoned

As part of his return home from Canada, Sitting Bull surrendered to the U.S. government on July 19, 1881. According to PBS: New Perspectives on the West, he had his son hand his rifle over to the commander of Fort Buford as a gesture not simply of surrender but as a step towards making friends of white Americans. He wanted one thing to be clear as he gave himself over: "I wish it to be remembered that I was the last man of my tribe to surrender my rifle."

He hoped this surrender and attempt at friendship would allow his people to travel freely across the U.S.-Canada border and grant him a reservation of his own near the Black Hills. Instead, he was sent to the Standing Rock reservation, but he wasn't there for long.

Once on the reservation, the U.S. Army grew fearful of his leadership and his influence over the tribe, believing that Sitting Bull would stir up trouble and incite another uprising. The army felt like they'd been backed into a corner, so they decided to arrest Sitting Bull before he became more trouble than they could handle. They moved their prisoner to Fort Randall in South Dakota where he would remain locked away for two years, unable to return to Standing Rock until May 10, 1883.

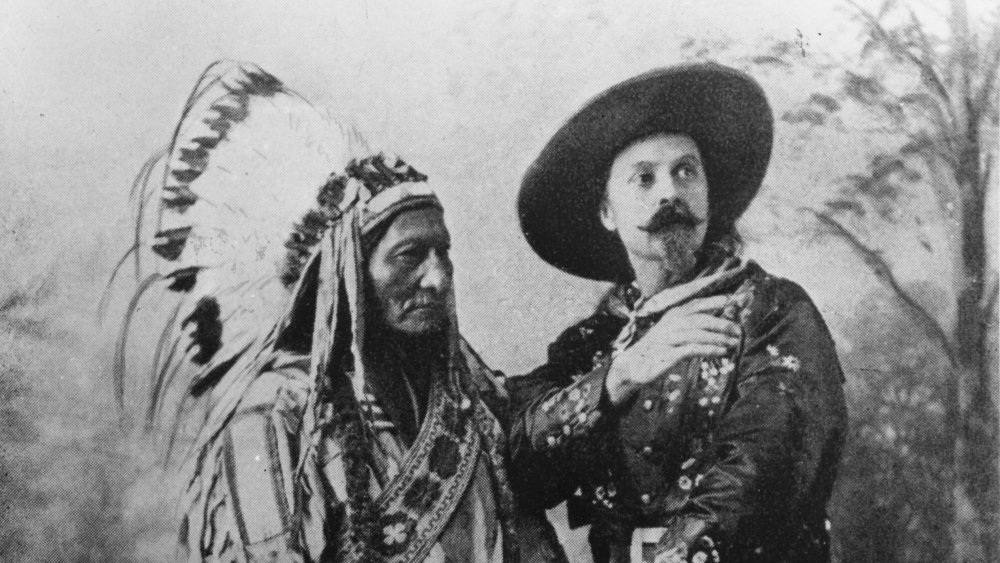

Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show gains a new attraction

It wasn't long after being released from his imprisonment that Sitting Bull was approached by the recruiter for Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, John Burke. Burke talked fast and smooth, trying to get Sitting Bull to join the show, but the chief had had plenty of encounters with this type of swindling white men before. He did end up joining the troop but not on Burke's terms. Instead, according to the Independent, Sitting Bull negotiated $50 per week, expenses paid, and the rights to his autograph and all photographs he appeared in.

While working for the show, Sitting Bull's performances consisted of being paraded around an arena while simulated battles between "cowboys and Indians" were played out around him. He wasn't expected to act out scenes like the other Native Americans in the show. No. That wouldn't be good enough for the hero of the Battle of Little Bighorn. The hero that show-goers loved to hate. Sitting Bull would perform a solitary lap around the arena while spectators booed, as the production had planned for him from the beginning. He was an attraction. Nothing more.

It didn't take long for Sitting Bull to grow tired of the show and quit. The money was good for the time, but not good enough to have Sitting Bull basking in degradation. According to Biography, Sitting Bull commented on his departure, saying: "[I] would rather die an Indian than live a white man."

Sitting Bull returns to his people once again

Finally, Sitting Bull returns to his people on the Standing Rock reservation where he moved into a cabin next to the Grand River. Under the United States' rules, Native Americans were required to give up most aspects of their cultural traditions to assimilate with white culture, but Sitting Bull refused, according to Biography. He lived with two wives when the rules said one. He practiced his traditional spiritual ways when the United States' government demanded he convert to Christianity. He did, though, according to PBS: New Perspectives on the West, send his children to a Christian school because he believed the future generations of his people would need to know how to read and write in English.

The vision before the Battle of Little Bighorn wasn't the only vision Sitting Bull would have. Not long after returning to Standing Rock, he had a second premonition. In this vision, he sits beside a small hill where a meadowlark lands and speaks the words: "Your own people, Lakotas, will kill you." Sitting Bull would spend the next five years on the reservation waiting to see if his second vision would come true.

The Ghost Dance plays a part in Sitting Bull's story

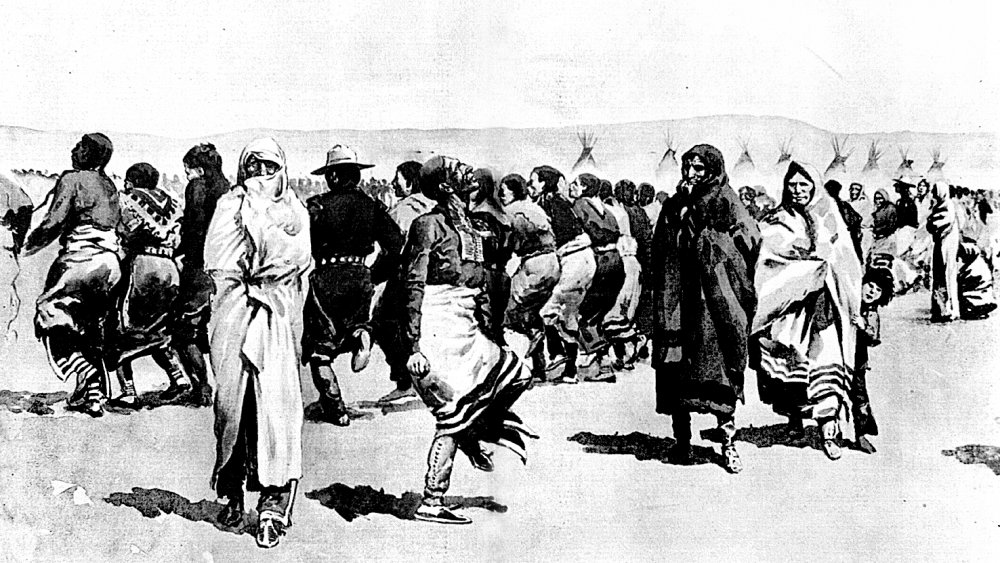

Sitting Bull was able to live in peace for a few years after returning to Standing Rock, but only a few years. As soon as Native Americans across the country started taking up the Ghost Dance in 1889 things became hectic once again. The Ghost Dance was a religious movement meant to reestablish native traditions that the American Indians were being stripped of by colonizers. Here's the problem: These indigenous ways were a form of resistance. Traditions were dangerous to the U.S. government's control over the reservations and the native peoples who inhabited them, and they couldn't have the echoes of uprisings disrupt their dominance.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the Ghost Dance was believed to accomplish several feats — some supernatural — including the return of the dead, the ridding of the whites, and the reestablishing of Native lands and traditional ways of life. Dancers in the ritual would often receive new songs from their rituals and believed to be healed of physical ailments. The ritual participants would receive "ghost shirts" meant to protect the wearer from bullets. The U.S. government was so fearful of this movement that they opened fire on the dancers at the massacre of Wounded Knee, where the shirts failed to protect the dancers and the brunt of the Ghost Dance movement came to an end.

A tragic end for the great leader

Two weeks before the Ghost Dance movement would end with the massacre at Wounded Knee, Sitting Bull's second vision would come to fruition. Though it's uncertain whether Sitting Bull ever joined the Ghost Dance movement himself, the U.S. government was worried that he may endorse the ritual and use the excitement from the movement to stir up rebellion among the Native American community.

Sitting Bull was awoken by Indian police at 6 a.m. on December 15, 1890, according to History. When they arrested Sitting Bull, he didn't go quietly and the ruckus drew a crowd. The scene quickly grew chaotic. A young Lakota man shot one of the Indian police. The police officer then shot Sitting Bull. The great Sioux chief and medicine man, the symbol of Native American resistance, died instantly from shots to the head and chest.

His body was buried in the military cemetery at Fort Yates but that would only be a temporary resting place for the great leader. Sitting Bull's family would exhume what they believed to be his bones in 1953 and move them to a place where they would overlook the Missouri River in South Dakota. Hopefully, granting a peaceful rest to a soul whose life was filled with struggle.