The Truth About The Real Rosie The Riveter

Who was the real Rosie the Riveter? If you were alive and paying attention in the early 1940s, you'd have known that a) there was a war on and b) adult males were off fighting that war and c) the United States was trying to ramp up its industrial output in order to equip those adult males with the materiel required to defeat the forces of tyranny to the East and the West. We probably don't think twice about it today (or at least we shouldn't), but back in 1942, the idea of a factory staffed almost entirely by women was a novelty. Throw in some other factors — women in that portion of the workforce, acquiring experience to produce the crucial goods quickly, efficiently, and safely. Throw in national morale — things didn't go well for the Allies in the early days of World War II, thanks to a guy named Hitler. The country needed internal propaganda, and fast.

To that end, at least three iterations of Rosie the Riveter popped up in the early days of World War II. The first, addressing the novelty of women in defense plant work, was a, well, novelty song, "Rosie the Riveter," extolling the work ethic and general stupendousness of a woman who worked on the production line, yes, running a rivet gun.

The inspiration for the song helped build fighter planes

According to All That's Interesting, the inspiration for the song was a 20-year-old woman, Rosalind Palmer (later Walters). She came from old money and a prep school background to take her place building fighter planes in Connecticut. She was profiled in 1942 by a newspaper columnist, and the story inspired songwriters Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb. The catchy tune was a hit for The Vagabonds, Kay Kyser, and others.

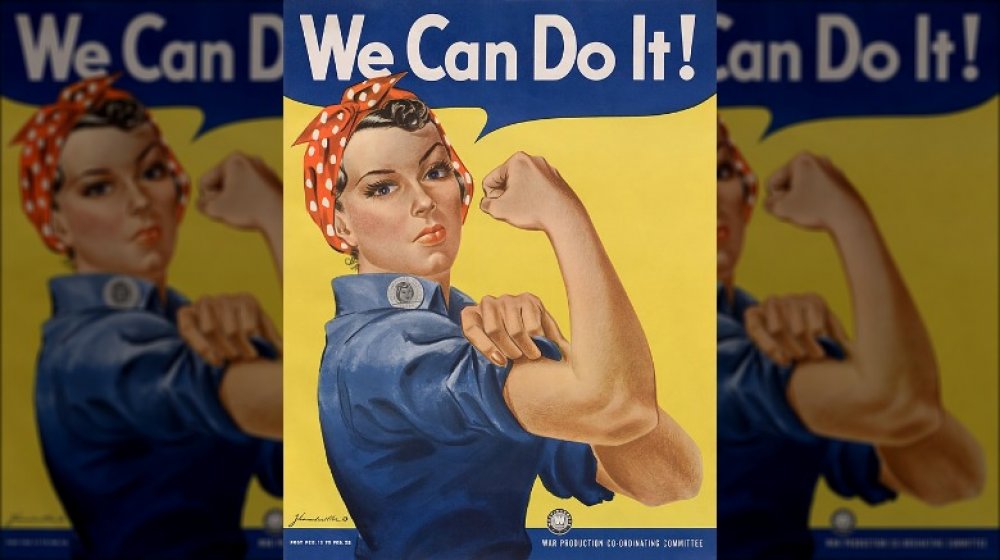

The "We Can Do It!" poster associated with the Rosie name wasn't actually named that. The image was created as internal inspirational art for Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Recent research makes the case that the woman who inspired that image was another 20-year-old defense worker, Naomi Parker Fraley who, according to Smithsonian, was photographed wearing the polka dot bandana as she bent over a lathe at the Naval Air Station in Alameda, California.

Yet another version of Rosie involves Norman Rockwell, whose cover for the May 29, 1943 edition of the Saturday Evening Post featured another young woman, with red hair and a rivet gun. That model was a 19-year-old, Mary Doyle Keefe, who was a neighbor of Rockwell's and worked as a telephone operator. In real life she wasn't as muscular as Rockwell made her for the painting — he later called her to apologize. That painting, with Rockwell's series "The Four Freedoms," toured the country to raise money for war bonds.