False Things You Believe About The Great Depression

No matter how bad things get, always remember, they could be worse. Way, way, worse. The world could have ended back in the 80s during some dumb nuclear misunderstanding or something. The world could end today for pretty much the same reason. Global infrastructure could collapse and leave us all in the dark. There could be zombies. Well, that last one would actually be kind of cool but never mind. No matter how bad things get, they could always get even worse. And they have, too. You just have to look to the past and you'll find plenty of great examples. The Great Depression is one of them.

Just how bad was the Great Depression? Well, that depends on which historian you consult, what sort of political leanings that economics or political website happens to have, and which group of 1930s society you're actually talking about. The historical recollections of the Great Depression have changed over time, and a lot of what we used to believe has turned out to be wrong. Here is a list of some of the most common misconceptions about that awful decade.

Overindulgence during the 20s led to the Great Depression

The "Roaring 20s" have a reputation for being a time of partying and reckless spending. Rich people were buying overvalued stocks. The Great Gatsby was partying at his lavish mansion. Meanwhile, poor and middle class people got their hands on credit, and went kind of nuts buying all of those newfangled, life-changing appliances like vacuum cleaners and washing machines. And hey, you can't really blame them. Imagine being a housewife in the early 1920s and having to break your back washing clothes by hand and beating carpets, and then someone shows you a washing machine and a vacuum. You would absolutely go into all kinds of debt to get your hands on those things.

A lot of historians still think all that overspending and buying on credit helped usher in the Great Depression. Never mind that overspending and buying things on credit is still totally a thing in America and we haven't had another Great Depression yet, but let's just ignore that for a moment. The University of Virginia says that the case for Roaring 20s overindulgence is "surprisingly weak." Yes, there were a few people at the top who were buying overvalued stocks and doing risky things with their money, and yes, people bought washing machines on credit. But the era was also marked by economic growth, manufacturing, and slow inflation, so it's not really likely that all that activity was having a lot of negative impact on the economy.

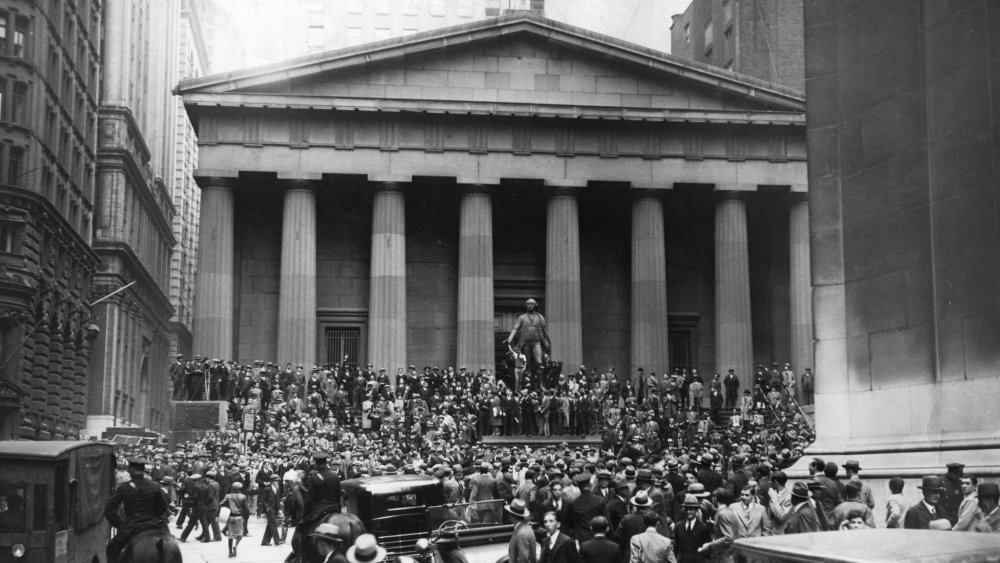

The stock market crash of 1929 caused the Great Depression

When the stock market crashed on Black Thursday, almost everyone panicked. People who owned a ton of stock panicked. People who owned a handful of shares panicked. Everyone sold their stocks and that made the crash even worse. But did that lead to the Great Depression? That's what common knowledge says, but if you follow the rise and fall of the stock market just a few months forward to Good Friday, 1930, you'll see that the market had already rebounded and was pretty much at the same level it had been prior to the crash of 1929.

So what really did happen? According to Time, the Great Depression actually began in 1930, when the banks started to fail. That happened because bankers had made a lot of stupid choices about who they were going to lend money to over the years. But the problem with bank failures in the 1930s was that there was no protection for people who had their money in the bank, so when the bank went under it took all its customers' money with it. Meanwhile, people stopped spending money they no longer had, which led to a decline in demand for consumer goods and an increase in unemployment. Things started snowballing after that, until the low point of the Great Depression when the unemployment rate reached a staggering 25 percent.

It was mostly an American thing

The Great Depression began in America, but it reverberated around the world. By 1932, the economic downturn had reached Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, South America, and the rest of North America, so pretty much the only continent you could go to to escape the economic downturn was Antarctica, though in Antarctic life was still pretty sucky in a lot of very different ways. Anyway, by the early 1920s, global unemployment had reached epic numbers, with 30 million people out of work.

For people living in already-disadvantaged countries, the Great Depression was especially devastating. According to Digital History, international trade was down 30 percent. Western countries stopped buying stuff from countries that depended on agricultural exports, so the price of things like coffee, tin, and rubber dropped by 40 percent. And because desperate people tend to rebel, some governments responded by installing military dictators as state heads.

The rise of fascism, in fact, can be directly correlated to the Great Depression — in Germany, Italy, and Japan, leaders promised salvation in exchange for draconian social changes. Hitler made labor unions illegal and restructured the military, which had a positive impact on unemployment but, you know, Nazism. So poverty wasn't the only awful thing that was born out of those awful times.

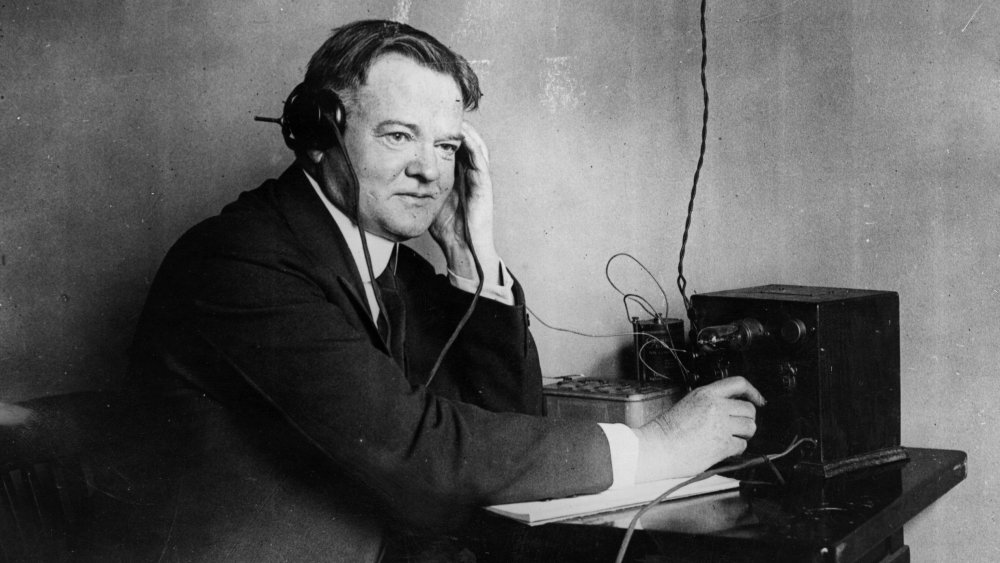

Herbert Hoover sat on his butt and did nothing

Whenever something bad happens, it's good to have a scapegoat. Some scapegoats totally deserve it. Other scapegoats are kind of just conveniently in the right place to be scapegoated. Herbert Hoover was one of the latter. According to the American Institute of Economic Research, Hoover did support free markets, but he was also smart enough to understand that something as major as the economic slide of the early 1930s required some sort of government intervention. In fact a lot of what Hoover did paved the way for Roosevelt's New Deal.

Getting people back to work is the best way to combat unemployment, and Hoover launched a series of policies designed to do just that, including a major public works program that included plans to build an enormous dam that was appropriately named "Hoover." He also established the Federal Farm Board, which helped slow the decline of food prices, and he created a program that granted low-interest loans to American businesses. Now, there's still plenty of debate over whether or not Hoover's policies actually helped, and some historians think his actions — especially the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which caused a massive trade war between the US and Europe — actually made things worse. But it is not true that he sat idly by while watching the nation backslide into poverty and despair.

Everyone in America suffered

Um, no. People who weren't already wealthy definitely suffered, but rich people sitting in their golden towers and looking down at the rest of the world didn't really suffer much at all, and a lot of them didn't really care too much about those who were suffering, either. It wasn't just the uber-wealthy — there were plenty of people who did well during the Great Depression, in fact, up to 40 percent of the nation were just fine, thank you very much. As for the rest of America ... 25 percent of the population had no income at all, while the other 35 percent was surviving, but only just.

The horrible specter of poverty impacted the country in a lot of ways. According to EyeWitness to History, some couples put off marriage because it just didn't make financial sense, and other couples put off divorce because that didn't make financial sense, either. Because people couldn't see having kids in the midst of an economic nightmare, the birth rate also dropped.

The Depression did a lot of psychological damage. Some men left their families because they couldn't handle the shame of unemployment. But the Depression also helped elevate women, many of whom went to work for the first time and often had an easier time finding jobs than their husbands did. Overall, the impact of the Great Depression largely depended on luck, how you were doing before the slide, and how resilient you were in the face of unprecedented financial challenges.

Nobody starved during the Great Depression

Herbert Hoover was famous for saying, "Nobody is actually starving. The hoboes are better fed than they have ever been." Because Herbert Hoover always had his finger on the pulse of the hobo population.

He was wrong. According to Digital History, in 1931 there were 20 cases of starvation in New York City alone. By 1934, there were 110 deaths in the city due to starvation. And it wasn't some big secret, either. Word of the starvation in New York City even reached the poverty-stricken African nation of Cameroon, which actually sent a small sum ($3.77) to the people of New York in the hope it would help someone get by.

That was just starvation in New York City. It's likely that people were starving all over the nation, and certainly in the already-disadvantaged countries that were also suffering because of the harsh realities of the Depression. But to be fair, starvation wasn't a huge problem overall in America. Families found new ways to get and conserve food. People who never grew food before suddenly became gardeners. They learned how to preserve and repurpose their scraps. Housewives changed the way they cooked, sticking to frugal ingredients and stretching their budgets. City gardens were established to help feed the hungry, and restaurants reinvented themselves to feed people humble fare at low prices. In many ways, it was a testament to the resilience of human beings in difficult situations.

The death rate went up during the Great Depression

It seems like kind of a given — quality of life goes down, death rate goes up. But that wasn't true during the Great Depression, in fact, the death rate actually declined during those years, even when taking into account the few people who starved to death and the increase in the suicide rate.

It's easy to use that intel to conclude that the Depression must have been good for people's health, but a study quoted by Smithsonian says it was really a mix of factors. There was an overall decline in deaths related to diseases like pneumonia and influenza, which you could speculate had something to do with the Depression since people who aren't working are exposed to fewer people, and therefore less likely to catch and spread a communicable disease (although the researchers Smithsonian quotes didn't seem to think so).

One type of death did have a really strong connection with the downturn — car accident fatalities went way down, mostly because people could no longer afford cars. Economic programs (also known as the "New Deal") that were put into place by President Roosevelt also had an impact on quality of life, and hence on mortality. But there were other factors that didn't have much to do with the Great Depression, like general improvements in sanitation and health care. "Whether health improves or worsens during hard times depends mainly on how governments choose to respond," the study's authors concluded.

Farmers fled the dust bowl for California in massive numbers

Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath popularized the idea of a Depression-era mass exodus from the Dust Bowl, but it didn't happen exactly the way it was memorialized in that classic piece of fiction. According to Chicago Booth Review, it wasn't farmers who fled the famously dusty and barren landscape of the Great Plains, it was mostly highly-skilled workers and some lower-skilled laborers. And they didn't all pack up and head to California, either. Of those that did flee, only 10 percent went to the Golden State — a whopping 52 percent actually stayed in the Dust Bowl, they just changed counties.

Of course the statistics ignore the part where life in the Dust Bowl totally sucked. The area, which stretched from North Dakota to Texas and from the Mississippi River Valley to the Rockies just happened to get struck by a drought at exactly the same moment as the banks were failing. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that the land had been overfarmed and overgrazed for decades, leaving it eroded and barren. The name "Dust Bowl" came from the soil's tendency to blow away with the wind, creating dust storms so severe that they blocked out the sun. So the people who stayed there not only had no money and little food, but their houses and lungs were constantly full of dust. It's not really surprising that those who could afford to flee often did.

The New Deal ended the Great Depression

Here's where you get the most disagreement about the facts of the Great Depression. How much did the New Deal help? Some economists will tell you it didn't help at all. Others will say it worked quite well. The truth is probably somewhere in between.

According to History, Franklin D. Roosevelt's famous package of economic programs titled "The New Deal" had a significant impact on the economy, but it wasn't the only thing the economy had going for it. It did pave the way for the labor movement, and it did establish a number of social safety nets including the American Social Security system. It also established regulations and institutions that have been largely responsible for the fact that we haven't ever experienced another similar depression, such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which insures bank accounts in the event of bank failure. And it put a lot of people back to work — the public works projects established under the New Deal gave jobs to millions of formerly unemployed Americans.

As far as immediate, Depression-ending impact, though, the New Deal wasn't it. During the heyday of the New Deal, unemployment remained high — around 18 percent — and the average American's income continued to decline. So the New Deal was really more about prevention than cure.

The New Deal helped everyone

The New Deal did help people, but it didn't help everyone. In fact some groups were actually hurt by the New Deal, in particular working black Americans. According to the Cato Institute, the New Deal's major piece of legislation was the National Industrial Recovery act of 1933, which created around 700 "industrial cartels." The industrial cartels had the power to do things like restrict output and raise wages and prices above where they would have been naturally. The end result of this was that a lot of low-skilled workers got priced out of the employment market, because employers weren't allowed to pay less than the minimum wage. Cato says this caused about 500,000 black workers to become unemployed as a direct result of the policy.

There were also new payroll taxes, and other policies that made it hard for businesses to hire people or raise capital. The Agricultural Adjustment Act, which passed the same year, actually cut farm production in order to drive up prices — and less production meant less work which meant fewer jobs. Also, people who don't have jobs are less able to afford the rising cost of food, so there was that.

Racism played a role, too. The Wagner Act of 1935 made labor union monopolies a thing, and those powerful labor unions were full of employed white guys who weren't interested in opening up their new club to unemployed black guys.

The beginning of WWII was the end of the Great Depression

People love to say that the Great Depression didn't end until America decided to band together to kick Hitler's butt. Collectively we can all agree that kicking Hitler's butt was a good thing, but the argument has also been used to justify wars of all kinds — war is good for the economy! Let's kick Canada's butt, too.

But just how much positive impact did World War II have on the Great Depression? Some. It didn't really end the Great Depression, though. In fact according to Forbes, the war actually ended up normalizing the crappy standard of living that people were already getting accustomed to after years of struggle. In other words, people kept on living off mac and cheese all the way to the end of the war, when reductions in government spending, taxes, and regulation finally changed America's economic situation for the better.

You'll also hear people talk about the decline in unemployment that happened at the beginning of the war — yeah, unemployment declined alright, because young men were getting drafted into military jobs and sent overseas. And gross domestic product rose, too, not because people's lives were getting better but because the US was making a lot of weapons and military equipment. So for sure, the war had some impact on the economy, but overall the standard of living didn't improve much until after the war was finally over.