The Truth About Marilyn Monroe's Death

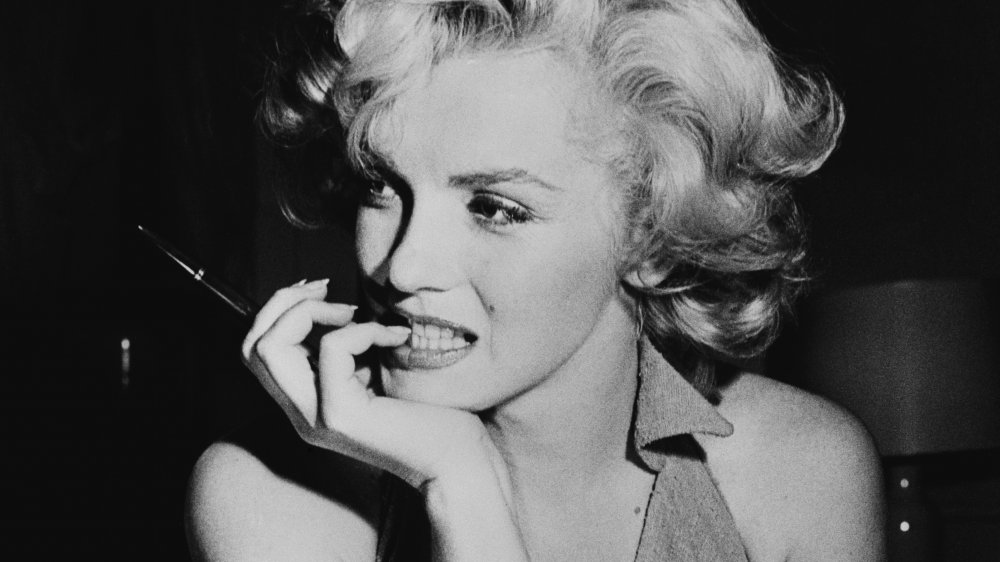

Marilyn Monroe shot to stardom in the 1950s as a curvaceous comedic vixen loved by men and women alike. She grew from pin-up girl to leading star, and eventually into a cultural icon. Even today, she remains the embodiment of femininity. Images of her grace everything from T-shirts and bedding to Andy Warhol's famous silkscreen prints.

But she is fixed in our cultural consciousness as forever young, blonde, and beautiful because she never got the opportunity to age gracefully. At just 36-years-old, Monroe was found dead in her home in Brentwood, California. Although it was officially ruled a suicide, suspicious circumstances surrounding her death sparked a string of conspiracies positing there may have been more to it than meets the eye. Rumors began to swirl that the real cause of her death had been covered-up by nefarious forces in the upper echelons of government.

Her fame continues well after her death, but she is remembered not only as a talented beauty gone too soon. Her legacy is also tainted with theories of crime, cover-up, and collusion that may never be put to rest.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The invention of Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe was an invention. She was born Norma Jeane Mortenson in Los Angeles on June 1, 1926, per Biography. She never knew her father, so she went by Norma Jeane Baker, taking her mother's last name. Gladys Baker suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and was incapable of caring for her daughter.

Monroe was raised in and out of foster homes, where she suffered violence and sexual abuse. To escape, she got married at 16 to a man named Jimmy Dougherty. While he served as a merchant marine in the South Pacific during World War II, Monroe did her part for the war effort by working at a munitions factory in Van Nuys.

In June 1945, she caught the eye of David Conover, an army photographer who had been sent by Army's First Motion Picture Unit to take pictures of the factory girls. With her curvy figure and pretty face, Conover recognized her potential. In January 1945, Monroe quit her factory job and began modeling as a pin-up girl for Conover. That August, she signed a contract with Blue Book Model Agency. By the time Doughtery returned in 1946, she had appeared on 33 magazine covers, per Vintage News. He disapproved of her career, and they divorced that September. But by then, she had set her sights to grander things. She signed her first acting contract, dyed her hair, changed her name, and moved to Hollywood.

A tragic end for Marilyn Monroe

By the 1960s, Monroe had won over American's hearts in films like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and The Seven Year Itch. Even the public release of nude photos she had taken as a financially struggling actress in 1949 only boosted her sympathy with both men and women, per author Michelle Vogel. Despite personal struggles, Monroe's success at the box office seemed limitless ... until the morning of Sunday, August 5th, 1962.

On the evening of Saturday, August 4th, Monroe called her psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson, complaining she couldn't sleep. She also phoned Peter Lawford, who was worried she sounded depressed and was slurring her words. He invited her to dinner with him and his wife, Pat, but she claimed she was too tired. She then told him: "Say goodbye to Pat, say goodbye to Jack (President John F. Kennedy) and say goodbye to yourself, because you're a nice guy,″ via AP News.

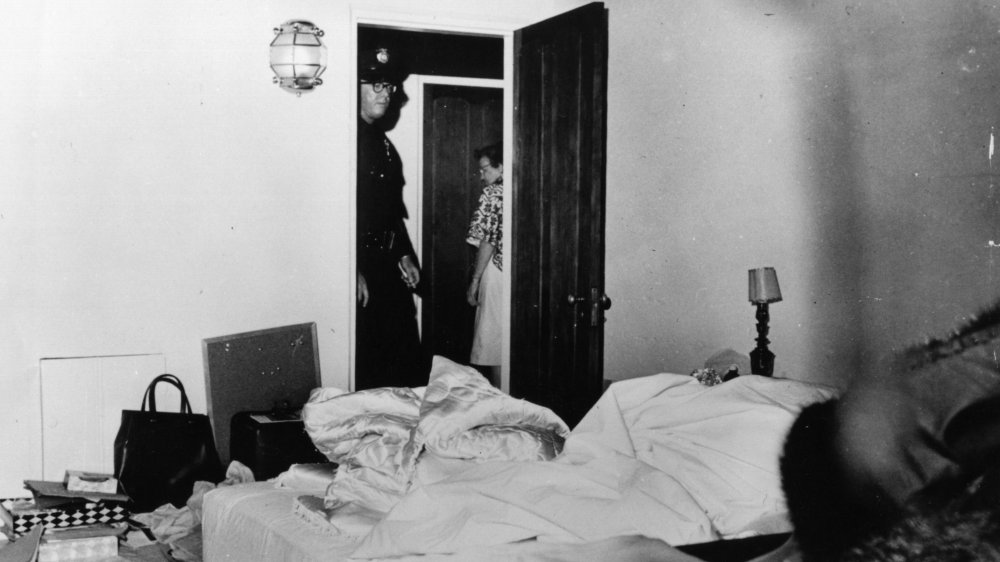

When the housekeeper, Eunice Murray, awoke around 3:00 am, Monroe's bedroom light was still on, but the door was locked. When she knocked and received no answer, Murray phoned Dr. Greenson. Per the Los Angeles Times, Dr. Greenson arrived around 3:30 and used a fire poker to smash the window and enter the room. Monroe was lying face down in bed, nude and clutching the telephone receiver, with an empty bottle of Nembutal lying next to her.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Marilyn Monroe's autopsy raised some questions

Monroe's body was sent to the Los Angeles County Coroner's Office for examination. The chief medical examiner, Dr. Theodore Curphey, did not perform the autopsy. Instead, it was performed by Thomas Noguchi, a junior medical examiner. According to Noguchi (via the Telegraph), "You start from the assumption that every body you examine might be a murder victim." He found no needle marks to indicate she had been injected against her will. The only trauma noted was "a slight ecchymotic area ... on the left hip and left side of lower back."

A toxicology report was performed, but only on her blood and liver, not any other organs. The report showed clear signs of overdose: 8.0 mg percent of chloral hydrate and 13.0 mg percent of pentobarbital (Nembutal), both fatal amounts. Nevertheless, skeptics would seize on this oversight as evidence of a cover up. Some also found it suspicious there were no pills or evidence of Nembutal's signature yellow dye in her stomach. But that was not particularly unusual for a habitual drug taker. Pills taken on an empty stomach would have been absorbed directly into her intestine, leaving few traces behind.

Ultimately, Noguchi felt there was nothing to indicate foul play. On August 17th, the coroner's office released their official statement, saying Monroe's death "was caused by a self-administered overdose of sedative drugs and that the mode of death is probable suicide."

Marilyn Monroe had a long history of depression

At first, suicide did not seem suspicious. It was well-known Marilyn Monroe suffered from depression and substance abuse problems. When he first met Monroe, her future husband Arthur Miller told her: "You're the saddest girl I've ever met," via the Ringer. Her drug and alcohol abuse was exacerbated by her chronic insomnia, according to Sarah Churchwell, author of The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe.

The Nembutal on which she had overdosed had been prescribed by her psychiatrist, Dr. Hyman Engelberg, to help her sleep, per the Los Angeles Times. She had also been undergoing a controversial analysis method called adoption therapy with Dr. Ralph Greenson for the past two years. Monroe had even previously overdosed on prescription pills.

Per Anthony Summers, author of Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe, in early 1962, Henry Weinstein, the producer of Something's Got to Give, called Monroe one morning after she failed to show up for work. When she answered, she was confused and slurring her words. Weinstein went to her house and found her in a barbiturate coma. Doctors arrived in time to pump her stomach, but the incident raised doubts about Monroe's ability to complete the film.

An unlikely marriage

Marilyn Monroe and playwright Arthur Miller met in 1950, but they were seeing other people. They reconnected in 1955 and began a romantic relationship. Monroe converted to Judaism to marry him in a small ceremony on June 29, 1956. Monroe was infatuated with Miller, writing: "I am so concerned about protecting Arthur I love him—and he is the only person—human being I have ever known that I could love not only as a man to which I am attracted to practically out of my senses about—but he [is] the only person ... that I trust as much as myself," via Vanity Fair.

Their honeymoon period ended when they moved to London in 1957. Monroe discovered a diary entry, in which Miller wrote "that he was 'disappointed' in her, and sometimes embarrassed by her in front of his friends," per Vanity Fair. She was crushed.

They returned to America, buying a house in Roxbury, Connecticut. But, clearly unhappy, Monroe had an affair with her Let's Make Love costar in 1960. Despite that, Miller pressured Monroe to star in the film adaptation of his story, The Misfits. Per Rare, she was reluctant to accept the role. She hated the sexism she experienced on set, and resented that the role was based on her life. While the press was busy promoting The Misfits, the couple divorced. It would be the last film Monroe would complete.

'A very, very sick girl'

Exhausted and depressed, Monroe committed herself to Payne Whitney's psychiatric ward, following her separation from Miller. She immediately regretted the decision. Upon arrival, her clothes and belongings were taken from her. She was forced to take a bath and put on a hospital gown. A doctor performed a full-body examination, over Monroe's protestations that she had just received one less than 30 days before, according to Vanity Fair.

Monroe recounted her traumatic experience in a letter to Dr. Greenson: "I picked up a light-weight chair and slammed it...against the glass intentionally ... I went over with the glass concealed in my hand and sat quietly on the bed ... I said to them 'If you are going to treat me like a nut I'll act like a nut' ... I indicated if they didn't let me out I would harm myself," via Vintage News. Four staff members forcibly carried Monroe to the seventh floor, where she was forced to take another bath. Monroe was kept in a padded cell in the locked psychiatric ward for three days.

"There was no empathy at Payne-Whitney ... The inhumanity there I found archaic. They asked me why I wasn't happy there ... I answered: 'Well, I'd have to be nuts if I like it here' ... [Dr. Kris] told me I was a very, very sick girl and had been a very, very sick girl for many years," she told Dr. Greenson, via Vintage News.

Something's Got to Give

Over the course of her career, Monroe's films had grossed $200 million, per the Los Angeles Times. But on her last film shoot, her director decided her star power wasn't worth putting up with her chronic tardiness, absenteeism, and overall difficult behavior. Monroe began shooting Something's Got to Give in early 1962. She was derided by her coworkers as "willfully disruptive ... [drifting] through her scenes in a depressed and drug-induced haze," per the Independent. That June, she was fired for "spectacular absenteeism," and sued by Fox for $750,000 for "willful violation of contract."

However, her costar Dean Martin threatened to quit unless she was brought back, saying, "I have the greatest respect for Miss Lee Remick and her talent, and all the other actresses who were considered for the role ... but I signed to do the picture with Marilyn Monroe and I will do it with no one else." She was rehired a few months later. Not everyone was pleased about her return. The film's screenwriter, Walter Bernstein, called her "a movie star who's getting her way, and who doesn't give a damn about anybody else."

Filming was set to begin again in October, but that would never happen. Monroe was found dead in August.

A Communist conspiracy

There were no real conspiracies surrounding Marilyn Monroe's death until 1964, when Frank A. Capell published The Strange Death of Marilyn Monroe. The short book claimed Monroe had been murdered by Communists on the orders of then-Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Capell believed Monroe and Robert Kennedy had been lovers, but the relationship soured when Kennedy refused to leave his wife. Furious, Monroe threatened to go public with the relationship. Rather than risk ruining his shot at the presidency, Kennedy supposedly dispatched a cabal of Communists to eliminate Monroe and cover up the murder, via the National Archives.

A staunch anti-Communist, Capell claimed: "When a person has become a liability or is getting out of hand, the Communist Party has no compunction in ordering his or her liquidation... Marilyn was deeply involved with left-wingers and identified Communists and her death has many suspicious aspects to it," via the National Archives.

The National Archives also reveals Monroe's doctor, Hyman Engelberg, admitted to being a member of the Communist Party. But Monroe's most public association with communism was her husband, Arthur Miller. Per Biography, the left-leaning playwright had been summoned to D.C. in 1956 to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee about party-affiliated meetings he had attended in the 1940s. Despite advice against it, Monroe publicly stood by Miller. Though he was cited for contempt, Monroe's popularity saved Miller from being blacklisted as many of his peers had been.

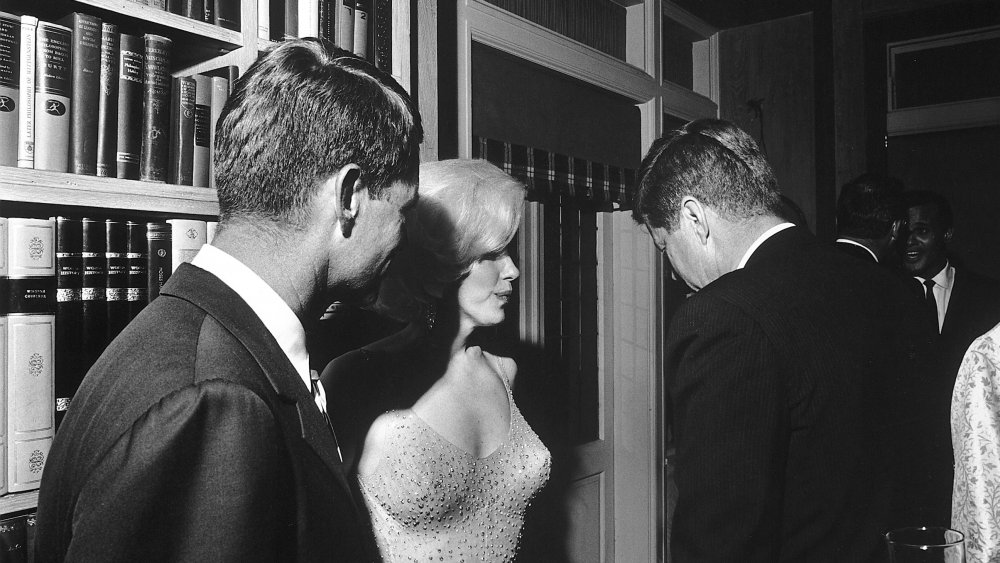

The Kennedy Affair

Monroe is said to have had relationships with both President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Tongues began wagging after Monroe sang her now-famous sultry rendition of "Happy Birthday" to the president at a Democratic fundraiser on May 19, 1962. JFK responded by saying, "I can now retire from politics after having had 'Happy Birthday' sung to me in such a sweet, wholesome way," per Biography.

While their relationship was salacious, it was nothing more than a casual fling. More troubling was Monroe's alleged affair with Robert Kennedy. Monroe was "led to believe his intentions were serious" and he would leave his wife for her, via the National Archives.

Peter Lawford, the last person to speak to Monroe, was the Kennedys' brother-in-law. She possibly feared Lawford, writing "about being afraid ... he might harm me, poison me, etc." per Vanity Fair. Some speculated Robert Kennedy had been at Lawford's house in Los Angeles the night she died. In his 1985 book, Anthony Summers presented the theory that RFK and Lawford were responsible for plying Monroe with drugs to render her incapable of exposing the affair. On the night of August 4th, she accidentally died of an overdose in an ambulance. To avoid implication, RFK wanted to get out of Los Angeles before news of her death broke. Lawford returned the body to her home and orchestrated a cover-up to make the overdose look like a suicide.

'The cover-up crime of the century'

By the 1970s, the rumor mill was in full swing. Claims began surfacing that Monroe had been murdered by Kennedy loyalists in the CIA. Allegedly, she had been privy to confidential information about a secret CIA plot to kill Fidel Castro. After being spurned by Robert Kennedy, Monroe planned to release the information, per the Chicago Tribune. To hide the scandal, the CIA injected Monroe with barbiturates and staged the death to look like suicide.

Jack Clemmons, the homicide investigator who was first on the scene at Monroe's death, was adamant that "she was murdered by needle injection by someone she knew and probably trusted ... This was the cover-up crime of the century–a matter of the Los Angeles Police Department and other officials here protecting a famous political family of the East who had good reasons to shut Monroe's mouth."

In his 1973 book, Marilyn: A Novel Biography, Norman Mailer raised questions over the integrity of the investigation, especially the autopsy. "The word was out to keep this thing a suicide, not to make it a murder ... If you're the coroner and you feel the official mood is to find evidence of a suicide, you wouldn't want to come in with murder," he wrote, via the Telegraph.

The 1982 inquest into Marilyn Monroe's death

In August 1982, the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office reopened the investigation into Monroe's death in light of new allegations. The Deputy Coroner, Lionel Grandison, came forward claiming he had been coerced into signing the death certificate. Grandison claimed "the whole thing was organized to hide the truth ... An original autopsy file vanished, a scrawled note that Marilyn Monroe wrote and which did not speak of suicide also vanished and so did the first police report. I was told to sign the official report–or I'd find myself in a position I couldn't get out of," via the Chicago Tribune.

Private detective Milo Spiriglio also claimed Monroe's diary had gone missing after her death. He believed the diary held damning information about the Kennedys, including information about the CIA's plot to kill Castro and the Kennedys' involvement with the mafia, per the CIA. He was confident not only that it still existed, but that it "may tell us who killed Marilyn Monroe." He even offered $10,000 to anyone who could turn up her missing diary, via the Chicago Tribune.

However, the diary never appeared, and the inquest failed to turn up any viable new information. Monroe's official cause of death remained suicide.

Marilyn Monroe's death was a tragic accident

A final tragic explanation is Marilyn Monroe's death was simply an accidental overdose. Monroe's career was on the upswing, and she had only recently purchased her Brentwood home. There was also no suicide note, although according to Dr. Robert Litman, the psychiatrist who headed the Psychiatric Investigative Team, suicide notes are left by fewer than 40 percent of people, via the Los Angeles Times. Monroe's close friend, Pat Newcomb, insisted the death was accidental, saying, "Marilyn was in perfect physical condition and was feeling great," and they had made plans to go to the movies the following day. Monroe had also made plans to meet with her lawyer, Milton Rudin, who claimed "she appeared to be happy."

According to the Psychiatric Investigative Team's report on Monroe's death, she had been seeking psychiatric treatment, with one of the main goals being to reduce her drug intake. She had been "partially successful" and "was reported to be following doctor's orders in her use of the drugs." They also reported: "On more than one occasion... she had made a suicide attempt, using sedative drugs. On these occasions, she had called for help and had been rescued. It is our opinion that the same pattern was repeated on the evening of Aug. 4 except for the rescue."

While Litman declared the case a "probable suicide," it is possible that on this occasion, she wanted rescue but was unable to call for help in time.