The Untold Truth Of Jefferson Starship

The San Francisco psychedelic hippie rock collective that called itself Jefferson Airplane produced some of the late '60s most memorable and definitive songs, including the druggy "White Rabbit," the bewildering "Somebody to Love," and the anti-Vietnam war "Volunteers." When the counterculture movement died down in the early 1970s, Jefferson Airplane experienced one of the most tumultuous band histories ever, with lots of musicians coming in and out over the years, many leaving acrimoniously and communicating with their ex-bandmates only through lawyers.

It's also probably the only band to find success in three distinct eras, with three distinct styles, and with three different names. The groovy Jefferson Airplane became the spacey Jefferson Starship, which became the overproduced '80s soft rock band Starship. No matter what the group called itself or what kind of music it performed, it was always stacked with rock legends like Grace Slick, Paul Kantner, and Marty Balin. Here's a look back at the long, strange trip of Jefferson Starship (or whatever you want to call it).

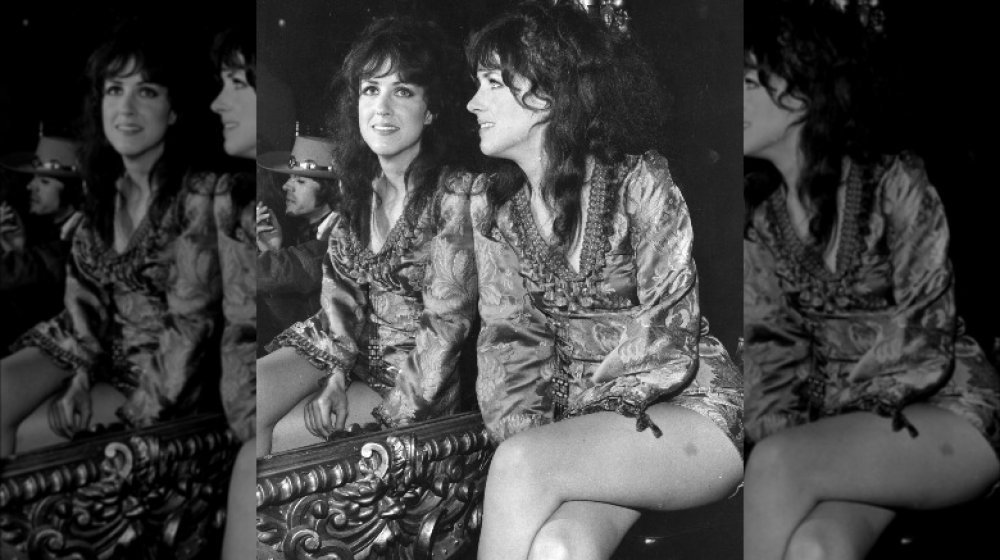

Singer Grace Slick wasn't the band's original choice

Jefferson Airplane is synonymous with Grace Slick. The singer brought charisma, high-register vocals, and a sense of menace to the band's songs, be it as a creepy guide through the Alice in Wonderland-referencing "White Rabbit" or the kitschy fun ov "Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now." It's hard to imagine any version of the band getting anywhere without Slick, which is odd because she wasn't anywhere near its first singer.

After a performance in San Francisco in the summer of 1965, singer Signe Toly was asked to join the still-forming Jefferson Airplane by founder Marty Balin, according to Rolling Stone. Toly (later Toly Anderson after a marriage) provided lead vocals on Jefferson's Airplane's debut album in 1966. By the end of that year, she was out of the band. The other members had their eye on a replacement, Sherry Snow of the San Francisco duo Blackburn & Snow. However, she wasn't interested, so Slick got the job.

Who wants to be Jefferson Airplane's drummer?

Original singer Singe Toly Anderson stuck around for less than a year with Jefferson Airplane, but she wasn't the only original member who didn't last for the band's long flight. While Spencer Dryden eventually secured the role of drummer for the band's late '60s glory days, he wasn't the first. That title goes to Jerry Peloquin, who, according to All Music, came to the attention of band starter Marty Balin when he was dating a woman who was friends with Balin's girlfriend. Peloquin spent just a few months with Jefferson Airplane, but he left before the group recorded its first album in favor of being a session and for-hire drummer before leaving music entirely to be a psychologist. Peloquin's replacement was Skip Spence, ostensibly a guitarist who moved behind the kit at Balin's urging. While he wrote the first single from Jefferson Airplane's second album Surrealistic Pillow, Spencer departed the group in favor of Moby Grape.

What's a 'Jefferson Airplane?'

The greatest band names are the ones that somehow suggest the group's unique sound while also maintaining an air of both grandiosity and mystery. For example, there's the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and of course, Jefferson Airplane.

As far as the latter is concerned, there's never been anyone in the band named Jefferson, and they've never recorded songs about aviation, so the reasons for the musicians picking that name must be symbolic or evocative. According to an extensive band history from Ohio State University, the true meaning of "Jefferson Airplane" is unclear, or at least unsettled. Per MTV News, the group named itself when San Francisco blues musician Steve Talbot told member Jorma Kaukonen of a fictional blues singer named Blind Thomas Jefferson Airplane.

But the band, known for its songs laced with drug references, could also be named after an item of marijuana paraphernalia. A "Jefferson Airplane" is a '60s slang term for a "roach clip" — a makeshift device used to hold a joint so that the smoker doesn't burn their fingers. Specifically, a Jefferson Airplane is a roach clip made by splitting a wooden match and inserting the burning joint inside.

Death, violence, and Jefferson Airplane at Altamont

Day-long (or weekend-long) outdoor concerts with multiple stages showcasing dozens of bands, like Coachella or Bumbershoot, originated in the late 1960s with three big events that both defined their cultural era and were historically significant for other reasons. Those festivals, of course, were the Monterey International Pop Music Festival in June 1967, Woodstock in August 1969, and the Altamont Free Concert in December 1969. And the only major band of the era (one who helped provide the soundtrack for the '60s hippie counterculture) to play all three was Jefferson Airplane.

Achieving this triple crown didn't come easy. Altamont infamously ended in the death of attendee Meredith Hunter at the hands of the Hells Angels, the motorcycle gang hired as security guards. "It was partially our fault," Slick told Rolling Stone. How so? Well, according to Slick, Jefferson Airplane had previously staged free concerts (like Altamont was) in San Francisco and had used the Hells Angels for security. "And they never hurt anybody," Slick said. "And they were good at it because people were afraid of them." Mick Jagger the Rolling Stones liked the idea and signed off on what would turn out to be a fatal suggestion.

And the band didn't escape Altamont unscathed, either. According to Paul Kantner, bandmate Marty Balin got into a scuffle with one of the Hells Angels. "He told them to f*** off, or something like that," Kantner told Music-Illuminati, causing the biker to strike him. When he came back to apologize, Balin "looked up and said, 'F*** you.' The guy hit him again."

Two bands members had a baby and caused a scandal

Some urban legends endure for so long because they sound so plausible. For example, it sounds totally reasonable that anti-establishment, countercultural icons and boundary-pushing rock stars like Grace Slick and Paul Kantner would have a baby and name her God. But according to Slick's memoir, Somebody to Love?, the facts are these.

In 1971, Slick, pregnant by her bandmate and lover Kantner, delivered a baby girl in San Francisco's French Hospital. As she held the newborn in the aftermath and afterglow, a nurse came into Slick's hospital room, "holding a framed certificate that looked like a high school diploma." The nurse then "pointed to an empty line in the document. 'What is your baby's name?' she asked." Slick, noticing that the nurse was wearing a crucifix necklace, blurted out, "'God. We spell it with a small 'g' because we want her to be humble.'"

The nurse, curious if Slick was serious, asked the rock star to repeat the name. Slick had been kidding, but she confirmed the choice, which the nurse "haltingly" jotted down. Slick then explained, "When [the nurse] was through filling in the irreverent name, she ran to the telephone to call Herb Caen, the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper columnist," who published Slick's joke as fact, thus spreading it around the world. As for the baby's real first name, as Snopes reports, it's China.

How Jefferson Airplane became Jefferson Starship

While still playing with Jefferson Airplane in 1969, bassist Jack Casady and guitarist Jorma Kaukonen formed a bluesy side project called Hot S***, renamed Hot Tuna for its self-titled debut album in 1970. By 1974, Hot Tuna had released four albums, so Casady and Kaukonen were obviously having way too much fun to go back to Jefferson Airplane.

That didn't matter all that much to bandmate Kantner, who in 1970 had released his solo debut, a concept album called Blows Against the Empire. The plot involved hippies who steal a government spaceship and fly off to start a utopian society on another planet. The album also included a significant amount of material about the impending arrival of Kantner's baby with Slick, and it was officially credited to Paul Kantner/Jefferson Starship — a play on the name of his main band but reflecting the record's science-fiction themes. And once the Hot Tuna guys were out of the band, Kantner and company adopted the new moniker to replace the old one, debuting it on the cover of the 1974 album Dragon Fly.

The constantly changing Marty Balin

While Grace Slick is the face of Jefferson Airplane (et al.) and Paul Kantner its most enduring member, the band was founded by Marty Balin. According to the Los Angeles Times, he started his musical career in the early 1960s folk craze, recording a couple of forgettable genre singles ("Nobody But You," "I Specialize in Love") before teaming up with a quartet called the Town Criers. While playing the folk scene, he met Kantner, and after buying a San Francisco pizza parlor and converting it into a club called The Matrix, he put together Jefferson Airplane to be its house band.

Balin proved to be a musical journeyman, stylistically. After Janis Joplin's drug-related death, he quit drugs and not coincidentally left the band he started in 1971. However, he was back with his old friends by 1975, by which point the group had rebranded as Jefferson Starship. It's Balin who wrote that group's biggest hit, the laid-back soft rocker "Miracles," which foreshadowed his future movements. Balin left Jefferson Starship in 1978 and re-started his long dormant solo career, scoring a top 10 hit in 1981 with the lite-FM staple "Hearts," a song so chill it makes "Miracles" sound like "White Rabbit." Sadly, Balin passed away in 2018, but the man's music is still playing today.

Grace Slick mocked a German audience while touring with Jefferson Starship

Grace Slick has been known to cause some controversy, and that was especially true in 1978. While touring Europe with Jefferson Starship, according to Ultimate Classic Rock, Slick fell ill with severe stomach issues. Thought at first to be food poisoning, a doctor diagnosed a far more serious ailment — appendicitis. However, the medic cleared Slick to perform that night, but she opted not to, and the band canceled its show in Wiesbaden, West Germany. While that certainly disappointed fans, her behavior at the next tour stop in Hamburg downright enraged them.

In the hours leading up to the concert, Slick reportedly got extremely drunk in her hotel room, triggering a booze-field breakdown that involved throwing bottles, refusing to get dressed for the show, and trying to get room service to bring her more alcoholic beverages. Somehow, Slick made it to the concert venue and hit the stage. Remembering that she was performing for fans in Germany, the main aggressor of World War II, Slick teased the crowd, yelling out, "Who won the war?" She also called people "Nazis" and did the "heil Hitler" gesture. It was such an ugly incident (and a public relations nightmare) that Paul Kantner asked Slick for her resignation. She quit ... but returned to Jefferson Starship three years later.

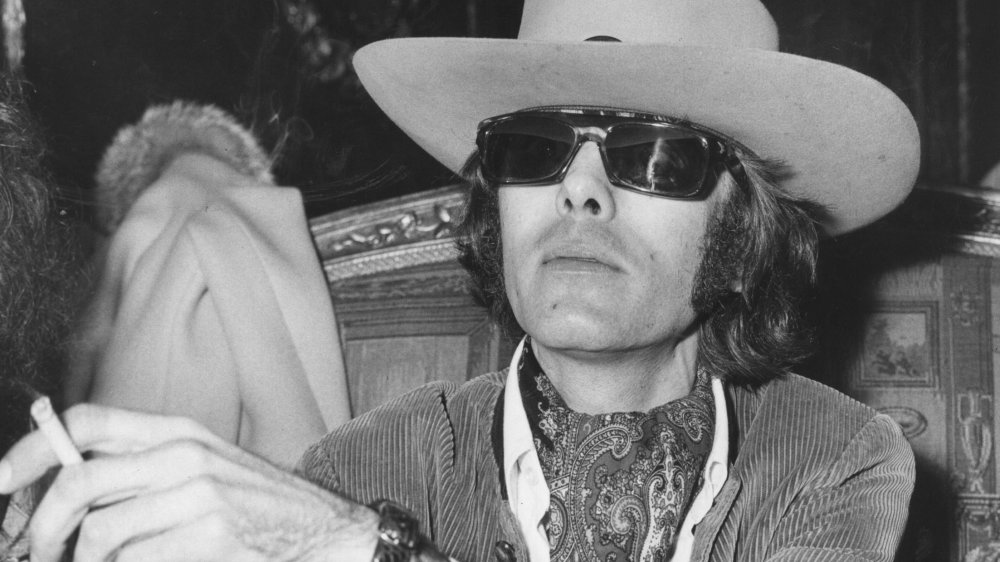

Jefferson Starship became Starship because of a lawsuit

So how did Jefferson Starship eventually morph into the extraordinarily '80s pop band Starship? Well, because a judge decreed it. See, Paul Kantner had formed Jefferson Starship out of his solo album, Blows Against the Empire, and he saw it through several hit albums. And that was a problem for Kantner. "I think we would be terrible failures trying to write pop songs all the time," he said in the band bio Got a Revolution! (via Ultimate Classic Rock) "The band became more mundane and not quite as challenging and not quite as much of a thing to be proud of."

Evidently, the rest of the group didn't agree, and in 1984, Kantner was so aghast at the Jefferson Starship album Nuclear Furniture that he stole the master tapes until he could convince the band to a more agreeable final mix. Shortly after that incident, Kantner left the group and took the name with him. The only original member of Jefferson Airplane left at that point, he sued to prevent his bandmates from ever performing under any name with "Jefferson" in it. So, according to The New York Times, the band lopped off that word and soldiered on as Starship.

Does anybody actually like 'We Built This City?'

The '60s ended on January 1, 1970, but some might say the spirit of the '60s ended in 1985, when Starship released "We Built This City." Jefferson Airplane, the band responsible for "White Rabbit" and "Volunteers," had morphed into the overproduced synth-pop combo Starship and recorded a song with a basic keyboard melody, a break for a traffic report, and lyrics about how rock n' roll is neat (all for a song that rocks so mildly it's a staple of adult contemporary radio stations to this day). The song hit #1 on the Billboard pop chart but not without some industry assistance. Helping boost airplay on radio, stations had the option to sub out the song's many San Francisco references with localized versions of the song, re-recorded by Starship-soundalike jingle singers.

And despite its success, "We Built This City" is one of the most loathed songs in history. Magazines like GQ have called it the worst song ever, and even one its writers doesn't give it much praise. Bernie Taupin, best known as the lyricist on countless Elton John classics, penned the song's first iteration, which he told GQ was "a very dark song about how club life in L.A. was being killed off and live acts had no place to go." Then "big-time pop guy and Austrian record producer" Peter Wolf took over "and totally changed it."

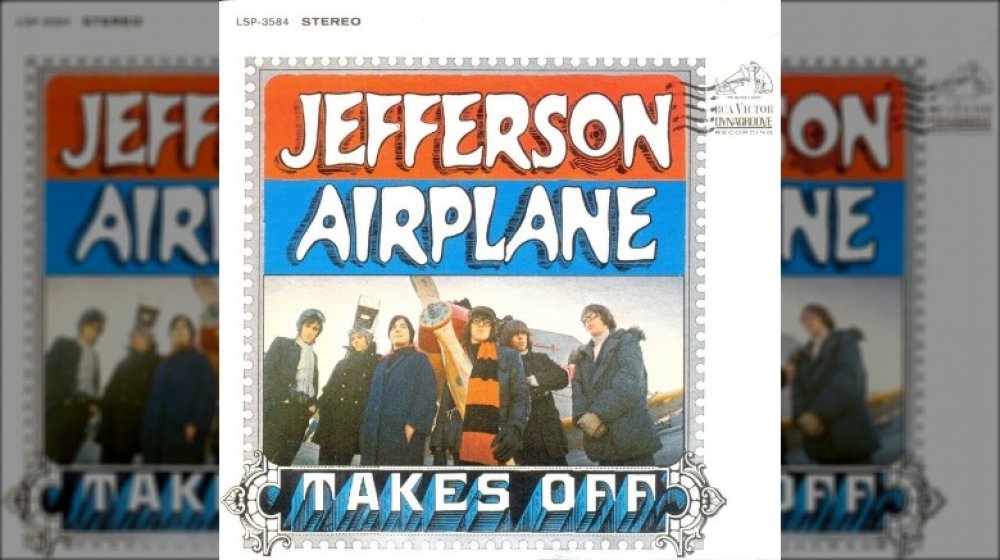

A lawsuit stretched out over the band's entire history

In 1966 and 1967, Jefferson Airplane released its first two albums, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off and Surrealistic Pillow, among the most influential and quintessential '60s psychedelic rock records ever. Matthew Katz was the band's first manager, briefly handling its affairs in 1965 and 1966 before he was fired. But because he'd signed a five-year management contract in 1965, Katz believed he was wrongfully terminated and thus entitled to a portion of the money generated by the band during the period he should've been managing them, particularly royalties for Takes Off and Surrealistic Pillow.

So in 1967, he sued for $2.5 million. After 20 years of legal wrangling, the lawsuit was finally settled in May 1987. According to UPI, Superior Court Judge Ollie Marie-Victoire dismissed the case before it was set to go to trial, ruling that Katz wasn't due any royalties. The main reason, according to the judge was that any courtroom proceedings would be tainted by doubt, as it would be "unreasonable, unfair, and almost impossible" for participants to accurately recall the finer points of business dealings from two decades prior.

During the Starship era, Jefferson Airplane reunited

To make the band's various lineup changes even more complicated, Jefferson Airplane reunited in 1989 ... while Starship was still a going concern. The new Jefferson Airplane came about from a 1988 performance in San Francisco by splinter group Hot Tuna, with special guest Paul Kantner. Unbeknownst to Kantner, the rest of the band had invited Slick to play a song. ”It started out as a joke on Paul. We hadn't even talked for a year, and we were battling legally," Slick told The New York Times. "The idea was that I'd just sneak in, stand at the side of the stage and come out and sing 'White Rabbit' and see what Paul did. Paul never got the joke, but he liked it, the audience liked it, and that's how it started.”

Kantner had recently reconnected with other Jefferson Airplane members in the short-lived KBC Band, and it was easy to recruit Marty Balin, suffering from a fallow point in his career, with no record contract and touring tiny clubs. Only drummer Spencer Dryden sat out the reunion, so the band hired John Mellencamp's drummer Kenny Aronoff. But despite a year in which fellow '60s stalwarts The Who and Paul McCartney staged successful comeback tours, the newly reformed Jefferson Airplane didn't fly with music fans. A new album, Jefferson Airplane, sputtered out on the album chart at #84, and that was that.