The Messed Up Truth About The War Of 1812

If there's any chapter of American history more poorly understood than the War of 1812, we're not sure what it could possibly be. Seriously, if someone stopped you on the street and gave you a pop quiz on the subject, how well do you think you'd do? You might be able to point out that it was fought between the U.S. and the British, that it started in 1812 (congrats on that deductive power), and that ... George Washington fought in it, maybe? Was he dead yet? Who was president in 1812, again? Was this the one with Gettysburg? At this point you might be feeling a bit embarrassed, but it's honestly not your fault.

The war is hardly discussed in classrooms and usually treated as either some kind of weird epilogue to the Revolutionary War that didn't really have much of a historical impact, or as a "Second War for Independence" during which Americans regained their honor from vicious British imperials and also wrote "The Star Spangled Banner" to really drive the point home. The truth, however, is much more complicated, more than a little stupid, and very, very messed up. Let's get familiar with the War of 1812. (And no, neither George Washington nor Gettysburg were involved.)

Everyone was to blame for the War of 1812

As it turns out, there's more than enough blame to go around for the war, since nobody was the victim and both sides, still bitter after the Revolutionary War, were constantly provoking each other. One of the most frequently cited reasons for the war was (and remains) the "Impressment" (essentially kidnapping) of American sailors into the Royal Navy, according to the Mariners' Museum. It's a bit more complicated than that when you consider the fact that lots of "American" sailors actually were British (maybe hiding from the Napoleonic Wars), and that the concept of citizenship was a lot more hazy at the time, but it was still highly controversial and seen as an affront to American sovereignty. Additionally, both Navies kept ambushing each other at sea, and the British were forcing all foreign (including American) merchant ships to dock in London and pay taxes to England before being permitted to trade with other European nations.

As far as America's faults, where to begin? Anglophobic conspiracy theories had reached a hysterical level among the public, leading huge swaths of the people (and their elected representatives) to demand war with Britain. Additionally, U.S. behavior toward (often British-backed) Native Americans was unimaginably cruel. The British were certainly fanning those flames by pushing Native American leaders to fight back, but there would be no flames to fan if it weren't for America's fanatical dedication to butchering the natives and stealing their land.

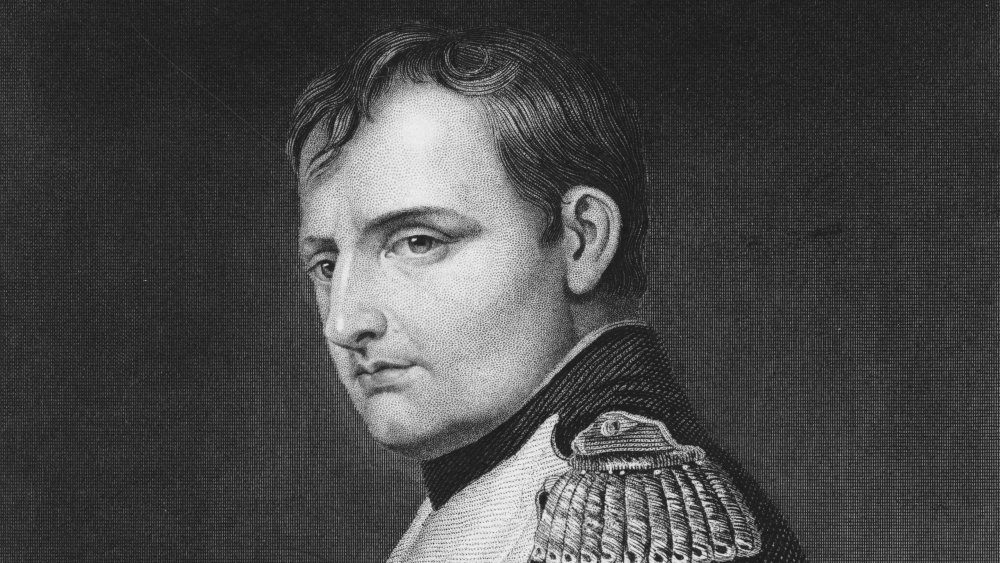

The U.S. didn't help stop Napoleon

It's easy (especially for Americans) to see the War of 1812 as a weird, isolated squabble between the U.S. and its former Imperial master. But there was one man who cast a shadow over the whole affair: Napoleon Bonaparte. Lots of Britain's behavior leading up to the fight (especially impressment and maritime taxation) can be explained by their conflict with him. To be fair, he did have to be stopped. The Emperor of the French, backed by his nigh-unstoppable Grande Armée, had been pillaging and plundering his way across Europe since the creatively named Napoleonic Wars began several years earlier. Napoleon had no bone to pick with the U.S., though, and even sold the Louisiana Territory to President Thomas Jefferson in 1803. It's no surprise that America still openly traded with France, but Britain was having none of it. They spent much of the war being unable to directly challenge Napoleon on land, choosing instead to support France's numerous enemies and use their superior Royal Navy to blockade the French. Neutral America's trading practices were a clear threat to the blockades' success.

The U.S. wasn't even unified by the War of 1812

The U.S. doesn't usually bother declaring war, and, when it does, it's usually fairly unanimous at the time of the vote. Not so with the vote to declare war in 1812. In fact, it's never been closer, per ThoughtCo. Long story short, northern states wanted to avoid war to protect trade interests, and voted accordingly. Southern states, seeing the war as an opportunity to gain new land that could be used for agrarian and slave-holding purposes, voted in favor. The final tally was 79-49 in the House and 19-13 in the Senate.

It didn't end there, either. In New York City and Baltimore, the National Park Service reports that riots broke out as enraged citizens voiced their feelings about the war. Those who sided with the Federalist Party felt the war was unjustified and little more than an excuse to seize land in Canada. State governments felt the nation was largely unprepared for all-out war with Britain. Still, patriotic fervor won out and only increased as the war dragged on. Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin wrote after the war ended that he felt it had brought the nation closer together. But whatever unity the war may have provided didn't last too long, as the Civil War was right around the corner.

The U.S. and Britain were not evenly matched in the War of 1812

Concerns about America's ability to actually fight the War of 1812 were very real. At the time the fighting broke out, the U.S. Navy had a dozen seaworthy battleships. Great Britain had roughly 500, and 80 of them were available for immediate duty in the Western Hemisphere. The U.S. had a pitiful 7,000 men in its Army, only 1,000 more than the tiny British garrison in Canada. All in all, the British had a field army of 243,885 men in 1812. The numbers would improve drastically for the U.S. as time went on, of course. By the time the war ended, the Americans had fielded 35,000 regulars and nearly half a million militiamen (for localized defenses) compared to Britain's 58,000 regulars, 4,000 militia and 10,000 Native American fighters.

Still, it was clear Britain was vastly more prepared for open war than the United States in 1812, lending some credence to pre-war concerns about the recklessness of diving into a fight. Luckily for the Americans, the ongoing war with Napoleon was always a more pressing concern and held down the majority of British resources, military strength, finances, and attention until the final stages of the war.

Everyone mistreated Native Americans during the War of 1812

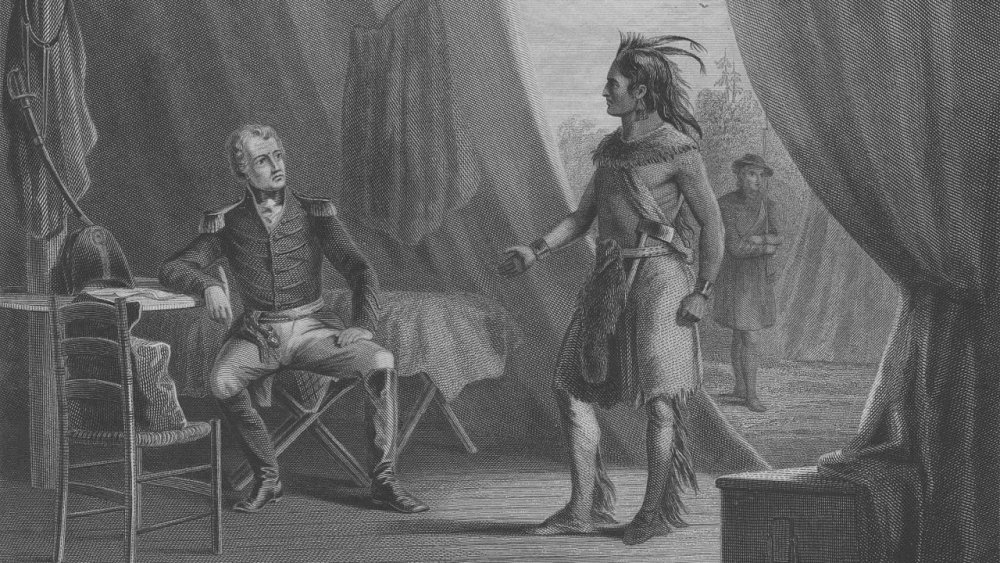

The U.S. was utterly vicious to Native Americans before, during, and after the War of 1812. Many natives wanted to appease the U.S. by resorting to negotiation and cultural assimilation, but these approaches did little to satisfy America's unquenchable appetite for land. History Channel recounts that one Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, wanted no part of the "turn the other cheek" strategy being employed by some of his contemporaries. Instead, he sought to unify the various threatened tribes and fight back against American encroachment.

His Indian Confederacy in the Northwest Territory (modern-day Ohio and Great Lakes region) was a force to be reckoned with when the war broke out. Organizing it was no small feat, as its constituent tribes and peoples were as different as any group of nations possibly could be, but they unified behind Tecumseh even when he allied them all with the British during the War of 1812 and rallied them to fight near the Canadian border. The British financed and supported Tecumseh, and fought with him in and around Detroit. However, it's obvious they only wanted to use the Native warriors as a proxy — better they die than British soldiers. Britannica notes that at the Battle of the Thames (in Ontario), the British effectively abandoned Tecumseh to be slaughtered by advancing Americans, led by future president William Henry Harrison. Tecumseh's death led to the evaporation of his confederacy.

The invasion of Canada didn't go as planned

The Americans quickly determined that a new war with Britain gave them the perfect excuse to invade and annex Canada, a long-time policy goal. Foolishly, these war hawks also believed the Canadians would seize the opportunity to throw off the chains of British tyranny and welcome them as liberators. This did not happen.

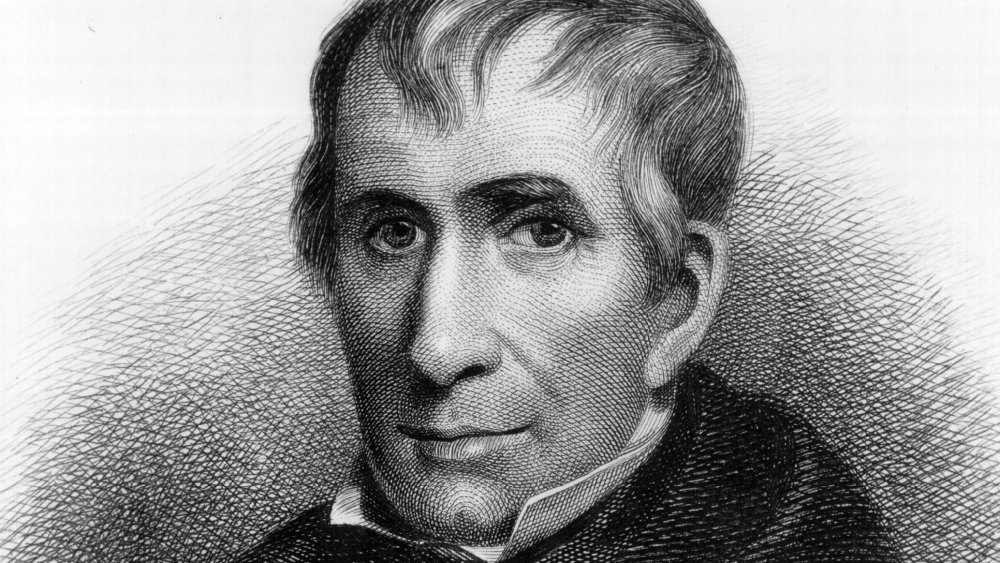

History Central records that upon invading Canada in 1812, U.S. Commander William Hull (above) threatened to visit the "horrors and calamities of war" upon any British citizen who failed to surrender, but promised wealth and freedom to those who joined them. This ham-fisted approach, backed up by only a few thousand poorly trained militia men, failed spectacularly. After being moderately resisted by British regulars, their native allies (led by Tecumseh), and Canadian militia, and having his lines of supply and communication threatened, Hull led the Americans on an embarrassing retreat back to Fort Detroit, which was then besieged by British and Native forces under the command of Major General Isaac Brock. While Brock was still preparing for an extended campaign against the Americans, Hull stunned both sides by surrendering his considerably larger force after a single light British bombardment that killed seven Americans (out of more than 2,500), citing the impending "horrors of an Indian massacre." Only a presidential pardon after the war saved him from literally being executed for incompetence.

The British sacked the U.S. capital

With Napoleon (temporarily) defeated, the British were finally able to turn more attention and resources to the ongoing, idiotic war with the Americans. In summer 1814, redcoats routed a considerably larger American force at the Battle of Bladensburg, near the modern D.C.-Maryland border, and subsequently entered and torched the U.S. capital, per History. Countless buildings were burned, including the Presidential Mansion (later rebuilt and named the White House) and the Capitol building.

President James Madison and most of the U.S. government managed to flee and hunker down for an evening in Brookeville, Maryland. It is still the only time a foreign power has ever occupied the American capital. Amazingly, on what has to be the single most chaotic day in the history of Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian reports that a hurricane-force storm descended on the city, putting out the fires and spawning a tornado that wreaked havoc on both American civilians and British troops, tossing cannons and killing several on both sides. The British returned to their ships after only 26 hours.

The U.S. did win a few battles in the War of 1812

It wasn't all disasters and humiliations for the Americans. Amid all the blunders and buffoonery, there were a few U.S. victories. In August 1812, the USS Constitution, a triple-masted heavy frigate (still afloat and fully commissioned by the U.S. Navy for ceremonial use today), dismasted and ruined the British ship Guerriere, per History Central, earning herself the nickname "Old Ironsides." It was a huge morale victory for the U.S. Just over a year later, the U.S. Navy captured six British ships on Lake Erie. This allowed American forces to recapture Detroit and defeat Tecumseh's Indian Confederacy at the Battle of the Thames.

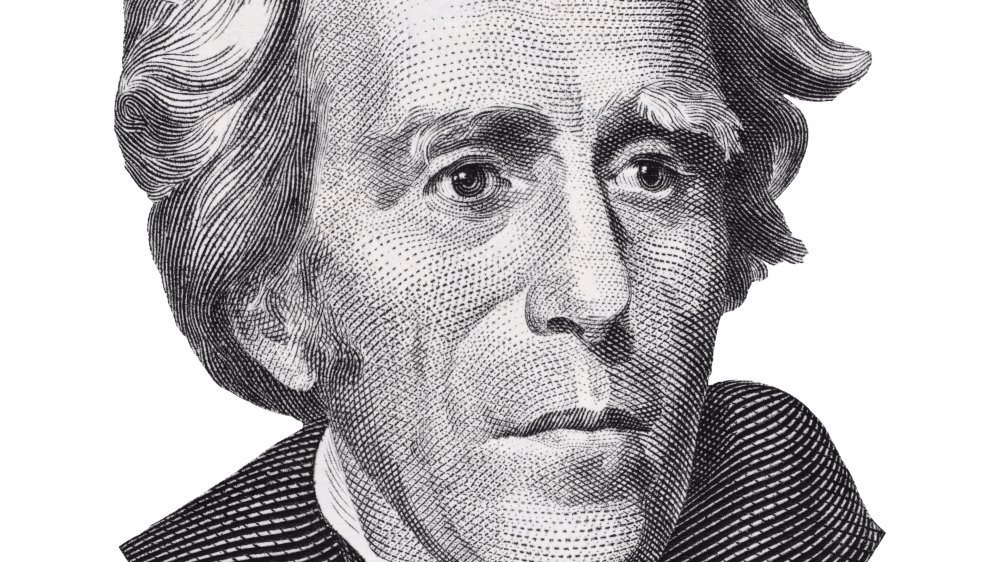

In March 1814, future president and face of the $20 bill Andrew Jackson crushed the Red Stick tribe near modern-day Dadeville, Alabama, during the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Jackson suspected the Red Sticks had been supplied by a British garrison at Pensacola, Florida. His intuition was confirmed when he scouted the area and found British soldiers there arming and training the same Red Stick Creek Indians who'd been raiding American settlements. He seized the town and laid the groundwork for the Battle of New Orleans, another lopsided American victory at the end of the war.

News traveled really slowly during the War of 1812

In the age of the internet, it's almost impossible to imagine a world in which we're not being constantly and immediately informed with live updates from around the planet. In the early 19th century, news didn't travel at the speed of light; it traveled at the speed of a horse or a wooden ship, and that's assuming nothing happened to the vessel en route. Both the beginning and the end of the War of 1812 were heavily influenced by the slow speed of news. The British Orders in Council — the English taxation of Europe-bound American merchant ships that helped lead to the outbreak of war — was actually rescinded days before the U.S. declared war on Britain, according to historian Don Hickey. However, news of the order's repeal didn't reach the Americans until after they had voted for war. By the time they found out, it was too late; America was committed.

And January 1815's Battle of New Orleans, America's greatest victory of the war in which Andrew Jackson's men bloodily repulsed a poorly executed British charge in Louisiana, took place a full two weeks after the Treaty of Ghent was negotiated in December 1814. According to Small Wars Journal, the British intentionally delayed the treaty and included phrasing that would let them keep territory they held at the end of the war. They hoped to win at New Orleans and have gained a new port in North America. But they lost the battle and the treaty wasn't signed by President Madison until February, so the British trick probably wouldn't have worked regardless.

Nobody actually won the War of 1812

The Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war in December 1814, restored relations between the belligerents to status quo ante bellum — to "the state existing before the war." In other words, it by definition ensured that nothing changed as a result of the War of 1812. Initial British demands that the Americans demilitarize the Great Lakes region, hand over land in Maine and agree to the establishment of a nation for Native Americans in the modern-day U.S. Midwest were never met. Why? Not because the Americans were great negotiators, but because the British were also helping facilitate the carving up of post-Napoleonic Europe at the time and feared that demanding border changes in the Americas would make them look like hypocrites. Back in Europe, they were denying Russian and Prussian demands for more land.

Impressment and free trade, two of the major issues that led to the outbreak of war, were barely mentioned in the treaty, per Khan Academy. After all, the British only restricted free trade and impressed American sailors in the first place to damage Napoleon, who had been (temporarily) defeated a few months earlier. Why would anybody care now? So the treaty essentially confirmed that the war began for reasons that had vanished by its conclusion. Perhaps more accurately, it accidentally confirmed the war began because some guys were itching for a fight and would take literally any excuse to have one.

Native Americans definitely lost in the War of 1812

The Treaty of Ghent may have enshrined into law the idiotic pointlessness of the war, but even with unchanged borders and barely touched international maritime law, it wasn't without consequences. American encroachment had chipped away at Native land and population for decades, and leaders like Tecumseh united previously warring tribes largely by pointing out that this new war was an opportunity for American Indians to improve their situation and maybe stop the loss of land. The British, they reasoned, would make powerful allies and perhaps help them negotiate more favorable borders.

Alas, it was not to be. Native Americans suffered 10,000 dead, on par with British losses and slightly behind the Americans. The Americans and the British ended up roughly where they began the war. Meanwhile, PBS notes that the natives suffered greatly and found themselves in an even worse spot at the end. American conquests east of the Mississippi River were all but confirmed by the failure of all sides to recognize a nation for American Indians (which briefly looked like a real possibility when negotiations began). Worse still, even more land grabs from the United States were likely to follow and that the land grabs were unlikely to meet any resistance from the international community. The British, and the world at large, had effectively abandoned Native Americans to the mercy of the United States, which had little love for them at all.

The War of 1812 was pretty dumb, but it had consequences

Although it took some time for this to become clear, and even apart from the impact it had on indigenous Americans, the war itself was far more consequential than the pointless-by-design Treaty of Ghent might suggest. First of all, it launched the careers of two future U.S. presidents: Andrew Jackson, who was in office from 1829 to 1837, and William Henry Harrison (above), who would infamously catch a cold at his 1841 inauguration and die a month later. Sadly, in both cases it was their vicious treatment of Native Americans that propelled them to fame — Jackson for his war against the Red Sticks and the resulting Battle of New Orleans, and Harrison for his crushing of Tecumseh's Confederacy in the Northwest Territory.

Beyond that, the war also ensured that Canada would never be part of the United States. The failed American attempt to annex it led to a rise in Canadian nationalism and has since become recognized as one of the defining chapters of the continent's northernmost country. The war also ended a period of suspicion and aggression between the United States and Great Britain, both of which would see their power grow immensely in the decades to come. When the next great threat to European peace emerged in 1914, the U.S. would (eventually) help Britain defeat it rather than trying to circumvent the British blockade. The two nations have been close allies ever since.