The Tragic History Of Chinese Emperors

The Chinese civilization is so old, it takes ancient to another level. By the time the country's last emperor left the throne in 1911, the nation of China was among the largest that had ever existed. And ruling it was no picnic. Across 4,000 years, around 49 dynasties gave it a try. One made it 289 years, while another didn't even get to its first anniversary.

The fates of the emperors themselves were just as varied. Only half of the rulers actually managed to die in office or abdicate by choice. The other half were more aggressively "retired" by assassination, forced abdication, forced suicide, or an uprising. Some emperors lived the royal life to the hilt, indulging in the abuses of power that seem to go hand in hand with absolute rule. Other emperors were little more than gilded prisoners. Life as an emperor in the Middle Kingdom wasn't all it was cracked up to be.

Purges as transfer of power between Chinese emperors

From the literal beginning, China was a nation steeped in violence.

The man who gave the country its name, Qin Shi Huang (Qin pronounced "Chin"), became the first emperor of a unified China in 221 BCE the way most "first" emperors did: killing his enemies. An early adopter of Total War, wherein nothing is off-limits to achieve victory, "The Qin was really the first state to really go into total mobilization for war," said Harvard University's Peter Bol to the BBC in 2012. The first emperor of the Qin dynasty , held onto power by erasing the past and controlling the present in what was known for centuries as the time of "burning the books and killing the scholars." Shi Huang's son and successor continued the violent tradition by murdering up to thirty of his brothers and sisters on his way to the throne before probably being assassinated himself.

Nor did the violence stop there. The Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) is widely regarded as the greatest of China's dynasties but their system of succession was so unstable that 12 direct heirs to the throne didn't survive long enough to get there. And the murdering continued to the end. Qing emperor Yongzheng, of China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing (1644-1911 CE), not only battled his siblings for years to get the throne but was even accused of killing his own father first.

Chinese emperors were seriously hit and miss

The problem with hereditary government is that it's kind of a genetic lottery. With almost three hundred rolls of the genetic dice, the Chinese empire was guaranteed to, and did, birth some rulers of legendary incompetence.

As the Jin dynasty collapsed (266-420 CE) in the fourth and fifth centuries China fragmented into multiple competing kingdoms. Although already blind in one eye when he took the throne of one of these kingdoms, Fu Sheng worked hard to earn the title of "one-eyed tyrant," according to the World of Chinese. Apparently sensitive about his disability, and too dumb to know better, he forbade the words like "missing" or "without," killing anyone who said them in his presence. He was deposed and killed in just two years for wanton idiocy and needless cruelty. Cruel, drunk, and stupid is no way to go through life, son.

Liu Shan was the second and last emperor of the Shu Han dynasty (221-263 CE), starting his reign at age 17 with every advantage. Son of a respected warlord and under the tutelage of Zhuge Liang, one of the era's greatest generals, Owlcation reports that Liu Shan nonetheless guided his empire into dissolution. He eventually surrendered his empire peacefully to the rival Wei kingdom and retired comfortably in their capital city. His ineptness was so profound that his childhood name is now a modern idiom for moron.

Being related to a Chinese emperor was a health hazard

It's good to be the king. So we like to think. Power, money, all the sex, fine food and clothing, opulence and comfort; the emperor's was a life anyone would envy. A life many people would, and did, kill for. Unfortunately, the killing wasn't restricted to that of the emperor. Like being friends with Spider-Man, belonging to the imperial family was dangerous.

Being a member of any powerful royal family generally means someone wants you dead. That it was long-standing Chinese tradition to execute entire generations of your enemy's family entitled some conquering regime changers to put not only the incumbent emperor to the sword but any potentially trouble-making relatives as well. The many uprisings and rebellions were usually led by people eager to cull the imperial herd as happened in the devastating but failed An Lu-shan Rebellion against the Tang dynasty.

The royals weren't even safe in their own homes. The path to upward mobility for members of the court, especially concubines, often led directly through some imperial corpse. Atlas Obscura says Emperor Hongzhi was the only monogamous emperor in Chinese history, in large part because his mother was murdered by his father's concubine.

The horrifying lives of the concubines

The palace was even more hazardous for the people working there, especially for imperial concubines. Practices changed over the dynasties and centuries but for the majority of China's tens of thousands of royal concubines, life could be hell.

For almost a millennium Chinese upper class women, including most concubines, practiced a peculiarly painful beauty regimen known as foot binding, per Smithsonian. Starting around age five or six, girls broke their arches and toes so that their heels and soles touched; the shorter the foot, the more desirable the woman — 3 inches was perfection.

As early as the Jin dynasty (266-420 CE) concubines were conscripts as well, chosen according to the particular criteria of that dynasty or emperor. For over fifteen hundred years, women and girls were kidnapped from or given away by their families and made to live with the emperor, hopefully providing him with sons. The South China Morning Post says while there was a hierarchy among the emperor's women, and opportunity for advancement, harems were often filled with jealously and rivalry — frequently leading to the women attacking, poisoning, and murdering each other. Of course, concubines belonged to the emperor — who could kill them anytime he wanted. As part of the royal household concubines were often subject to purges as well and could be killed by competing sons or warlords. And, according to Ancient Origins, as a job well-done, they could also be forced to join their emperor when he died.

When you're a Chinese emperor, beautiful women threaten your empire

While being the brood mare for a total stranger is inhumane, let's remember that said stranger is the emperor. Anyone with access to the emperor has some level of power, even if by their mere feminine presence — which apparently was regularly so beguiling that beautiful women, usually concubines, ended entire dynasties, according to GB Times.

The Four Beauties are the most beautiful women of ancient China, although at least one may be a fictional figure instead of a historical one. Their stories come from four different dynasties and for centuries epitomized the Chinese ideals of beauty, similar to Helen of Troy. Also like Helen, three of the Four Beauties, two of which were concubines, brought down a kingdom. One of them, Xi Shi, sometime referred to as the most physically beautiful of them all, was actually sent by a rival king as revenge.

Then there was King You, the last king of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046-771 BCE), according to China Knowledge, in no small part because he dropped his current wife and son for another woman. Bao Si was of surpassing beauty but never smiled. The only thing the king could do to make her smile was repeatedly light the signal towers warning the kingdom of invasion. This predictably aggravated his allies so, when an invasion did happen, King You was left to his fate.

Chinese emperors dealt with constant invasions

The threat of invasion was a constant reality in ancient China and foreign invaders ended many dynasties. Qin Shi Huang, first emperor of a unified China, began construction of the Great Wall over two thousand years ago to keep out the Xiongnu, northern nomads that he couldn't conquer. The Han dynasty eventually vanquished the Xiongnu after 200 years of war.

It took Genghis Khan and his grandson Kublai 60 years to complete their Mongol invasion and takeover of China. Exactly how many Chinese were killed during the creation of the greater Mongolian Empire is impossible to know but suffice to say that, according to Stanford University climate researcher Julia Pongratz, so many Asians died that the Mongol invasion altered global carbon dioxide levels. The Chinese empire they established, the Yuan dynasty, lasted over 200 years. The last Chinese Imperial Dynasty, the Qing, ended in no small part due to over a century of aggression and meddling by other imperial powers known in China today as the "Century of humiliation."

Of course, invasions don't necessarily come from outside. Before unification, and during the many periods afterwards when China was splintered into competing kingdoms, the country was embroiled in some of the bloodiest internecine warfare in the world. According to Business Insider, without even counting events of the 20th century, four of the 10 bloodiest wars in human history were Chinese civil wars.

Chinese emperors faced constant uprisings

Full blown civil wars aside, most of Chinese dynastic history is riddled with too many rebellions and revolutions to count. Entire books have been written about just the uprisings of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE). The Han (206 BCE-220 CE), Ming (1368-1644 CE), and Qing (1636-1911 CE) dynasties each have Wikipedia category pages just for rebellions.

According to Ancient History Encyclopedia, the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) is known by historians as economically prosperous and culturally dynamic but not exactly politically stable. Six rebellions occurred in the Song's first 80 years, the country split in two by 1127, and was overwhelmed by internal unrest for decades on end before finally succumbing to the Mongols. The uprising which spawned the split also inspired one of the four classics of Chinese literature, the story of 108 outlaws fighting the Song "To Render Justice for Heaven and Save the People."

China's emperors were beset by religious and ethnic independence movements simmering for centuries before boiling over, often contributing greatly — and colorfully — to the fall of a dynasty. The Han put down the Red Eyebrow rebellion, then faced the Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion before being taken down by the Yellow Turbans. The White Lotus, a political and religious group started during the Song dynasty, helped weaken the Qing before the anti-foreign, anti-imperialist Boxer rebellion ultimately exposed their incompetence and the empire fell forever in 1911.

Chinese emperors had weird family dynamics

Historically, royal families can be as violent and sexually broken as anyone. Roman emperors, French courts, and Russian tsars have filled books with disturbing and/or hilarious tales of debauchery and cruelty. A not-insignificant number of Chinese emperors were murdered by their own siblings and extended family but, of course, plenty of emperors had their own families killed.

Ancient History Encyclopedia reports the Tang dynasty's (618-097 CE) Empress Wu Zetian was the only outright female monarch in Chinese history and by all accounts a terribly effective, while controversial, one. She became a royal concubine at 14, finagled her way into the position of first consort, then empress consort, then empress dowager, before ruling openly as China's first female emperor. Wu accomplished this by murdering her own infant daughter and blaming the emperor's wife who she then had killed too, although Smithsonian Magazine suggests these accounts should be taken with a grain of salt.

At the age of 15, Liu Zeye ascended to the throne of the Liu-Song dynasty (420-479 CE) but was under the impression that his father would have preferred his younger son as successor. The new emperor convinced his sibling to commit suicide and then had his sons killed. Liu eventually went full-Caligula and is said to have brought both his aunt and sister into the palace for intimate relations. He was assassinated by his uncle when he was 16.

A Chinese emperor's successor might destroy everything

As if killing his brother and nephews weren't enough, Liu Zeye further disrespected his father by rescinding all laws passed by his imperial predecessor. Although usually not done to their own fathers, a change of policy during a change of administration isn't really unusual. Still, it would sting to know that your accomplishments or designs were deliberately upended by your successors — fortunately for the emperors, they were usually dead by that time.

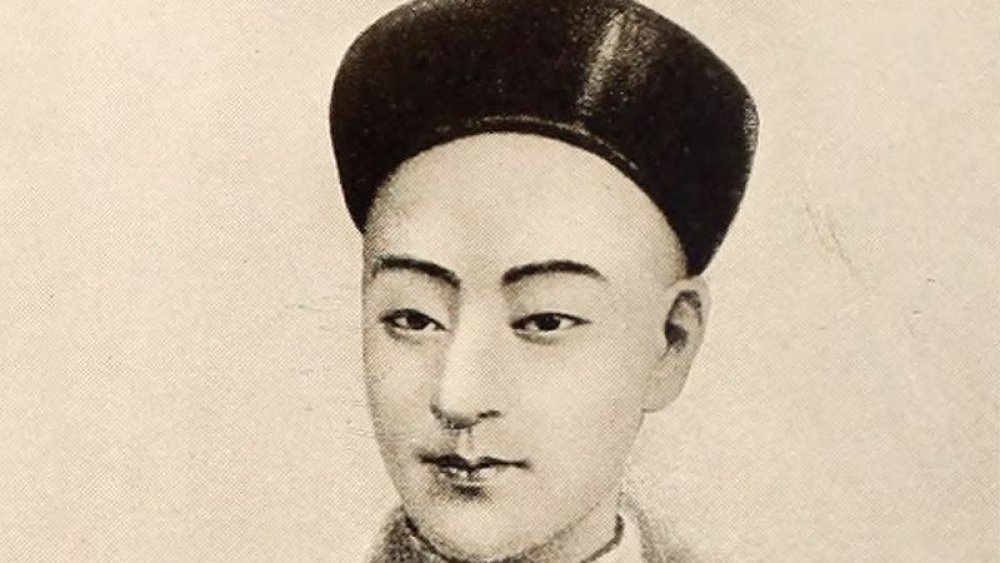

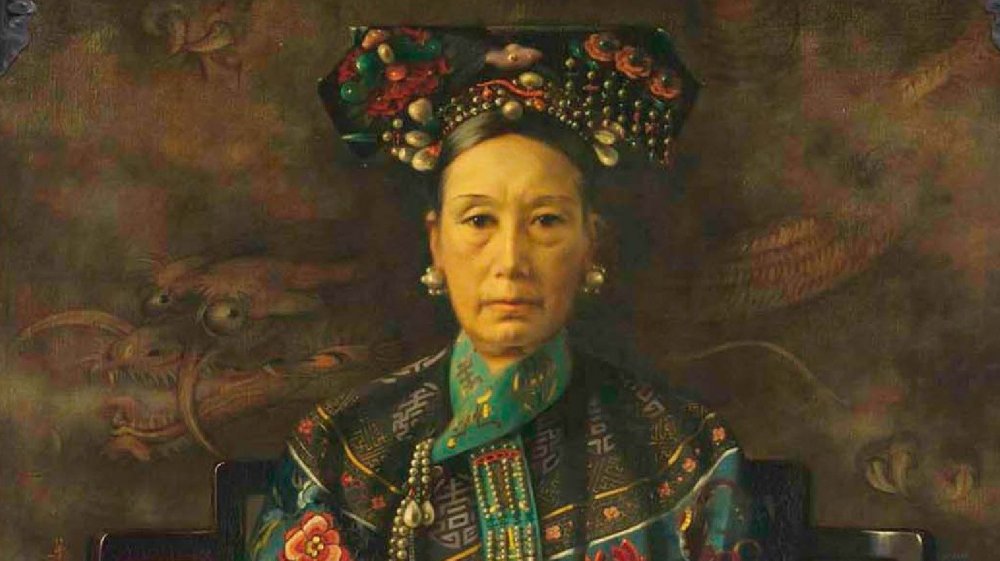

The Encyclopedia Britannica records an exception would be Empress Dowager Cixi, last real ruler of the Qing dynasty and imperial China (there was technically one more emperor but he was two when Cixi died so...) After China got a thorough drubbing in the First Sino-Japanese War the emperor, Cixi's son, pursued the Hundred Days of Reform to modernize the country and reshape the government. So the Empress Dowager supported a coup against her own son, reversed the reform policies, and took power — which she never relinquished. Cixi ruled (from behind a literal screen, as described by National Geographic) until her death in 1908.

Far more common was the example of Liu Bang who, prior to becoming the first Han emperor, joined the rebellion against the Qin for the express purpose of overturning their repressive policies. Or the reformist Emperor Wang Bang, only emperor of the ill-fated Xin dynasty (9-23 CE), who was killed by a peasant uprising for his efforts.

Chinese emperors were completely isolated

Leaders living apart from their subjects is not unusual, indeed it may be the standard. The trope of royal families enjoying cushy lives completely divorced from the real world circumstances of the common folk is found in literature and legend all across the world but China's last dynasties, the Ming and Qing, really set the bar for self-isolation.

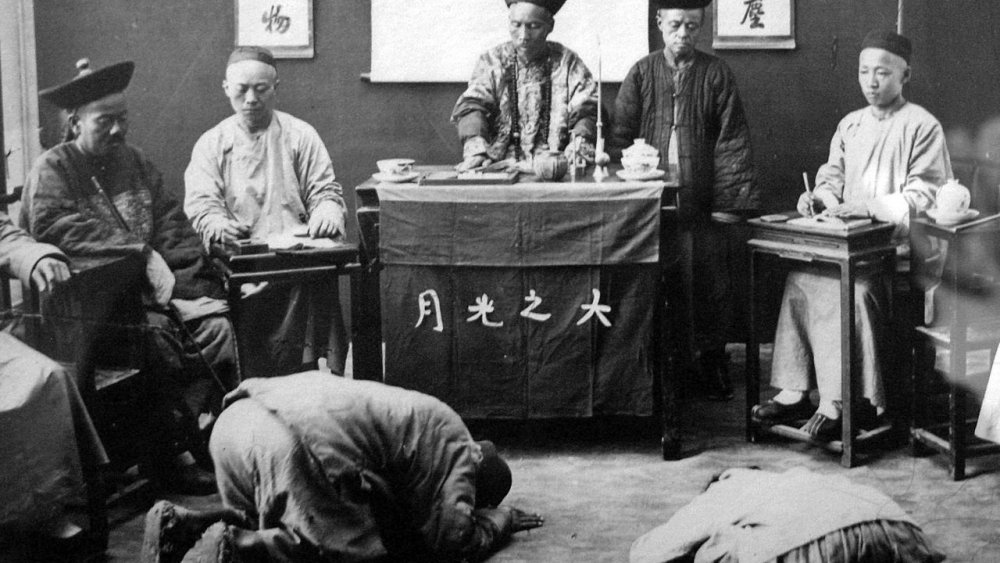

China's emperors had long set themselves far above their citizens, anointed to lead as the literal Son of Heaven. For over two thousand years, anyone approaching, or approached by, the emperor had to kowtow; prostrate on their knees with their forehead touching the ground. Ancient History Encyclopedia says in addition to his own fleet of custom-carriages the emperor also had his own personal roads which no one else could use and even his own unique first-person pronoun.

The color yellow had been associated with nobility since the Han but the Ming and Qing appropriated it completely and it was illegal for anyone else to wear. The imposing Forbidden City in Beijing was not merely the seat of imperial power it was, as the name implies, an intact, fully functioning city in its own right. There was nothing the emperor needed that his thousands of staff couldn't procure or the tens of thousands of square feet and 98 separate buildings couldn't accommodate. That would be if the emperor had the time to do anything, his responsibilities to the vast Chinese bureaucracy required rigid adherence to absurdly time-consuming protocol and tradition.

There were plenty of military rebellions

The Mandate of Heaven bestowed on all China's emperors was not a birthright, it was earned — and it could be revoked. Emperors who allowed the country to fall into poverty and chaos or lose face and prestige had obviously lost the Mandate and were often removed by force, frequently by their own generals.

Ancient History Encyclopedia says the Song dynasty was started by a military coup, but ironically, while the Song was an economically prosperous and culturally verdant period in which Chinese art, sculpture, literature, and music all reached new heights, it neglected the military. After centuries of fragile peace with their neighbors, the Song empire became the latest to fall to the Mongols.

There were massive coups involving millions of people and going on for years, like the one led by general An Lushan against the Tang dynasty which lasted eight years and cost up to 36 million lives. Then there were events like the 1461 coup by Ming general Cao Qin, which failed within a single day, resulting in the deaths of almost everyone involved. A failed coup against Qin Shi Huang solidified his position as King of Qin, allowing him strength to become the first emperor of a unified China. Of course, a successful coup against his son resulted in the end of his empire just 15 years after he started it.

There was so much corruption

Since ancient times, gift-giving has been widespread in Chinese culture, especially in politics and business, described as guanxi. Even today, writes Mary Stzo in the Fordham International Law Journal, "Guanxi, which literally means 'relationships' or 'connections,' is widely acknowledged as essential for successful business dealings in China." Guanxi isn't exactly bribery, but let's just say the practice has always left the ground fertile for corrupt officials.

A hallmark of collapsing governments is corruption and, considering the many Chinese dynasties toppled in uprisings and the many prominent reformers in Chinese history, ancient China was regularly corrupt. Bribery and graft were so endemic, and so brazen, that the names of corrupt officials are still known hundreds of years later, per People's Daily.

By the late imperial era, China had turned inward. For almost five centuries, China eschewed the outside world and, just as the increasing rigidity of tradition restricted the movements of the emperor, so some traditions encouraged corruption such that illicit income in the Ming and Qing dynasties was calculated by University of Missouri researchers to be 14 to 20 times as much as official income. Ultimately, Qing corruption was so bad that an international customs agency was established to collect taxes on import/export business in large part because local officials couldn't be trusted, accounting for an astounding one-third of all revenue.