The Truth About The Founding Fathers You Don't Know About

While we know several of the more famous Founding Fathers (a term which wasn't even applied to them until the 20th century) like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and Benjamin Franklin, there were plenty of others. A whole lot more, actually. Over 50 people signed the Declaration of Independence, and those weren't necessarily the same people who signed other documents like the Constitution or Articles of Confederation.

Basically, it seems anybody involved with politics at the founding of the United States was invited to sign the country's framing documents, and lots of people took the offer. While we might think of the Founding Fathers as good, honest, philosophical men, that wasn't necessarily true for all of them.

Just like any group of mismatched people, some of them were a little weird, some of them were even outright criminals, and some were not people you'd invite over for dinner, under any circumstance.

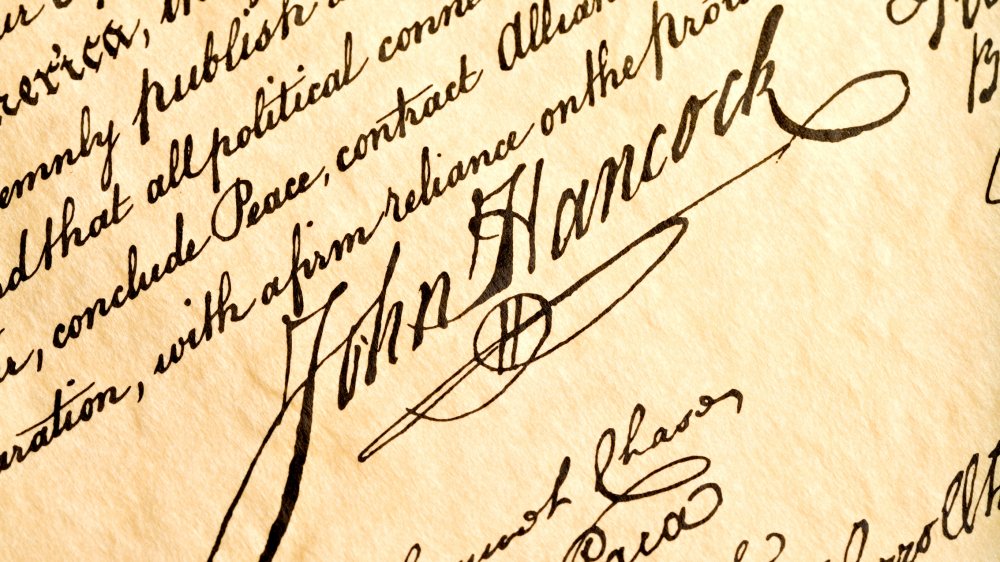

John Hancock was a famous smuggler

While you might have heard the name John Hancock before, it's likely that you don't know much about him other than his famous, oversized signature. But while the man's name is now synonymous with signing a document, elaborate penmanship was not the only thing upon which John Hancock left his John Hancock. Turns out, he was a big-time shipping magnate, although a more appropriate way to put it would be that he was a notorious smuggler.

While John Hancock encouraged the Boston Tea Party, it turns out the reason why was sorta underhanded. Hancock had been smuggling Dutch tea in for years and basically monopolized the market on it. Imported British tea was expensive, and while they did eventually raise the taxes on it, what doesn't get much mention is that the English dropped the price of the tea before the new taxes, actually making it cheaper than Hancock's smuggled tea, according to the Boston Tea Party Historical Society.

Hancock's buddy Samuel Adams (who we'll get to later) thus organized the Boston Tea Party, decrying the increased taxes. So all that tea that got dumped into the harbor just made John Hancock's smuggled Dutch tea all the more valuable. Tea wasn't Hancock's only business, either. He also smuggled glass, lead, paper, and molasses. Han Solo only wishes he could smuggle as much as John Hancock did.

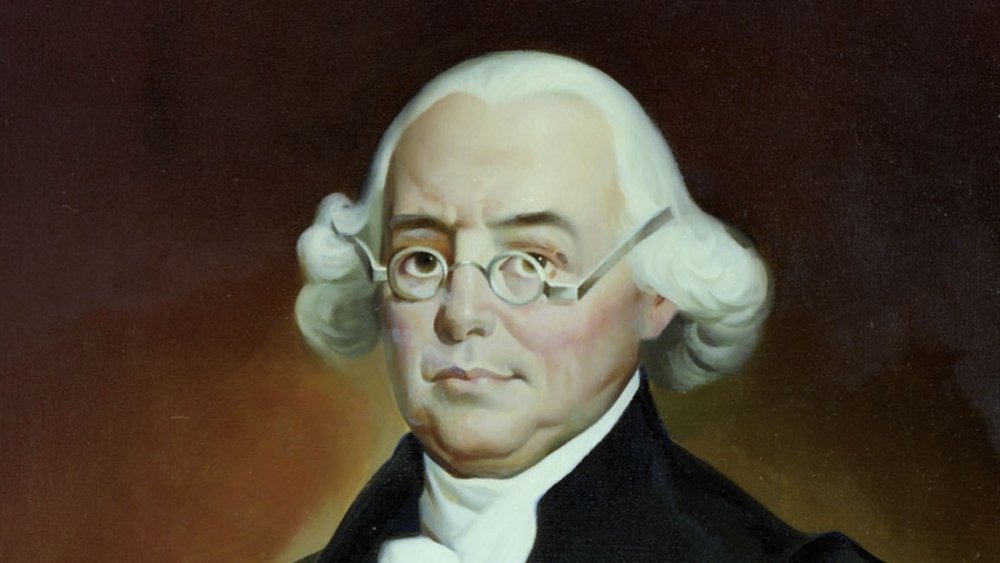

James Wilson was a Supreme Court Justice who wound up in prison

While we all know the first president, little thought is given to the earliest Supreme Court justices. James Wilson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and representative for Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress, was a well-known and well-respected name in law in early America. So much so that George Washington appointed him one of the country's first Supreme Court justices, according to Yale Law.

While Wilson had the chops to serve at the highest level of law, he also had something else — a mountain of debt. Wilson was a big investor in land deals and married into money, giving him lots of cash to throw into speculative real estate. Unfortunately for Wilson, this did not work out well. The land deals soured and Wilson ran out of cash, at which point he took out loans to make even more land deals in hopes that he'd strike it rich on one.

It turns out that real estate was not Wilson's calling in life, because those deals also fell apart, leaving Wilson not just broke, but in a massive financial hole. In the early days, America still had debtors' prison, and it didn't matter what his day job was. Wilson was thrown into a New Jersey prison and, after being released, fled to North Carolina to avoid ending up in another one. He died there, penniless and in shame.

Francis Hopkinson helped design the American flag

Everyone knows who created the American flag, right? It was Betsy Ross, and she sewed it by hand! But maybe not. Ross's claim to fame wasn't established until over 100 years later, when her grandson claimed that she created it without any solid proof. While there's plenty of evidence that she sewed lots of flags for the early U.S., historians are largely skeptical that she actually designed it, according to Colonial Williamsburg.

What's more likely is that the flag's design was a collaborative effort, and there is evidence for this, according to HowStuffWorks. Francis Hopkinson, a representative in the Continental Congress for New Jersey and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, seems to have had a hand. He is known to have designed other things, like the seal of New Jersey, the Treasury seal, and the Great Seal of the United States.

The evidence for this is a letter Hopkinson wrote to the Board of Admiralty asking for compensation for designing the flag. Specifically, he requested a whole bunch of wine. The request was denied, however, because the flag was a collaborative effort and Hopkinson wasn't the only contributor. While we don't know the extent of his work or who else helped with the design, it does seem that Hopkinson was at least involved to some degree (and he really liked wine).

Samuel Adams wasn't really a beer guy

In 1748, a young Samuel Adams inherited his father's brewery, and today we have Sam Adams beer as a result, right? Surely the brew that bears his name has something to do with his legacy of crafting Boston lager, or so one would think. Well, not exactly. Sam Adams is made by the Boston Beer Company and is only so named as a tribute to the real Samuel Adams, and only since 1985.

It turns out, the real Sam Adams wasn't much of a brewer. After taking over his father's business, it fell apart and went bankrupt within a few years. Also, it wasn't a brewery, as they only made malted hops, which brewers would then use to create beer. Samuel Adams was a maltster and not a brewer at all, and apparently the whole business didn't interest him much, according to History.

Instead, Adams found he was far better as a politician, writer, and public speaker. He became famous for his organizing skills, such as when he created the Sons of Liberty or set up the Boston Tea Party. Adams spearheaded several movements in the early days of American independence and, naturally, was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. So when you think of Samuel Adams' legacy, maybe focus on that stuff and forget about the beer thing.

Gouverneur Morris died in the most horrifying way possible

One of the younger Founding Fathers, Gouverneur Morris was born in New York in 1752, and by the age of 25, was a representative in the Continental Congress and signed the Articles of Confederation. Of course, he had already earned his master's degree at the age of 19, so it's not like he wasn't qualified.

Morris had some views that would certainly be considered unusual today, according to Laws.com. He was in favor of a strong central government, not a common sentiment in America's early years. Morris thought only wealthy landowners should be able to vote, as he feared poor people would sell their votes to the rich. He also thought that any future U.S. states, namely those out west, should not be considered equal to the original 13 colonies, as the wilds could not produce "enlightened" people.

Perhaps strangest of all were Morris's... extracurricular activities. In 1780, Morris lost one of his legs. He claimed this to be because of a carriage accident, but long-standing rumors state that it actually happened after he jumped out of a married woman's window when her husband came home. Then, there was the matter of his death. In 1816, at age 64, Morris passed away due to complications resulting from sticking a whale bone into his urethra to try to remove a urinary tract blockage. Ouch.

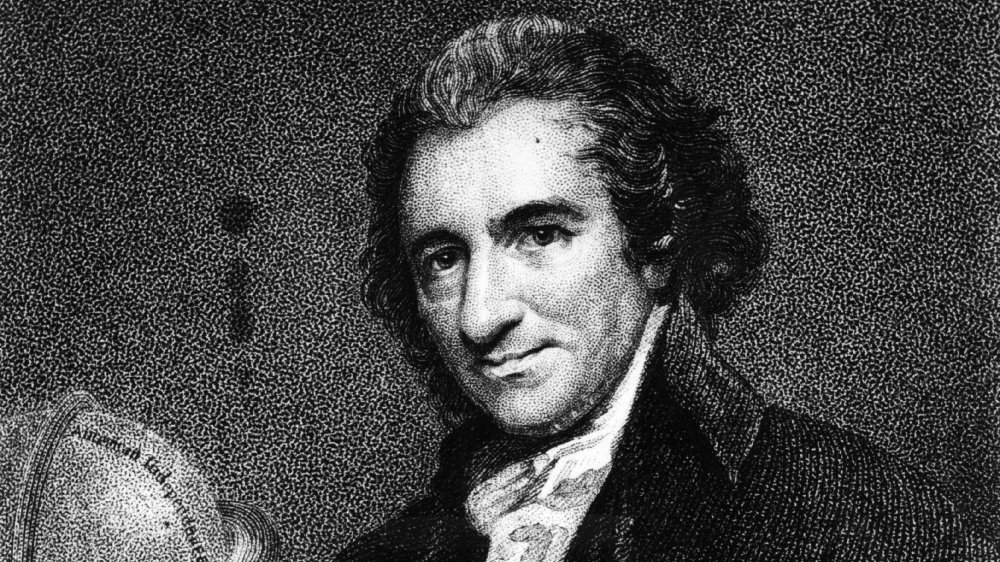

No one knows where Thomas Paine's remains are

You might not recognize Thomas Paine's name offhand, but you've probably heard of his pamphlet, Common Sense, which inspired many American colonists to rebel against British rule. While he never signed any of the country's founding documents, his influence coursed throughout those who did, according to the Library of Congress.

But, later in life, Paine fell out of favor. While most of the Founding Fathers were Christian deists, Paine turned to atheism late in life, and ended up writing several pieces decrying organized religion and Christianity in particular, a view that was highly unpopular at the time. As such, when he died in 1809, he was a pauper and his funeral was only attended by six people.

While that might be sad enough, something even stranger happened after he died. A decade later, his frenemy William Cobbett had his remains exhumed in order to give him a proper burial in England. When he returned to England to raise money for a tomb for Paine, he was ignored. Paine's remains stayed in Cobbett's family after his own death, but were sold by his son to avoid bankruptcy. Over the centuries since, the bones have been sold and traded, parceled off and moved around. While a few scattered pieces of Paine are extant today, the majority of them have long been lost.

Dr. Benjamin Rush was an influential early psychiatrist

While many Founding Fathers had day jobs in addition to their political work, one in particular stands out. Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and member of the Continental Congress, was first and foremost a medical doctor, and quite a famous one at that. A staff member of the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, Dr. Rush was on the front lines for the 1793 yellow fever epidemic of Philadelphia, as well as several other epidemics in the city, according to the University of Pennsylvania.

Not only that, but he was appointed to be a Physician General of America's Revolutionary War military hospitals, meaning he was in charge of treatment and administration of not just regular hospitals, but those for soldiers during a very bloody war. Later in life, he was even made Treasurer of the United States Mint by President John Adams.

What's most remarkable about Dr. Rush, though, is that he was an early proponent of psychiatry. While most doctors of the era were more than happy to write off the mentally ill, Dr. Rush instead worked toward diagnosing and treating mental illness, albeit in rudimentary ways. Dr. Rush was a big fan of bloodletting, and he also invented the "tranquilizing chair," which was meant to be an alternative to the straitjacket. While these methods seem barbaric now, they were actually a huge improvement to the way we had been treating psychiatric patients before.

Lemuel Haynes was a black abolitionist preacher

When we think of the Founding Fathers, we typically think of old white guys, many of them slave owners, with powdered wigs and pointy-toed shoes. While most of the Founding Fathers were white and older men, the powdered wigs and pointy-toed shoes were probably optional. But one of the lesser-known Founding Fathers might surprise a lot of Americans: He was a black abolitionist, and his name was Lemuel Haynes.

Haynes was the child of an African father and a white mother. He was abandoned shortly after birth, presumably because his very existence was taboo at the time, and sold into indentured servitude until the age of 21, according to PBS. Young Haynes loved to read and became a devout Christian, even giving his own sermons. When released from his indenture, he studied to become a preacher and was possibly the very first African American to minister to a white congregation, something completely unheard of at the time, though it didn't last long due to prejudice among his parishioners.

While Haynes never signed any formative documents and didn't have a big political presence during the founding of America, his writing was very influential among those that did, earning him a lot of praise and inspiring several political leaders to take on an abolitionist stance. Sadly, it took nearly a century before abolition did occur, but Haynes' writing is still considered highly groundbreaking for the time.

William Blount was the country's first impeachment

While impeachment was a big word in 2019, it was far from the first time such a thing had been brought up. In fact, the first time an impeachment occurred in the federal government was in 1797, not long after the country's founding. Senator William Blount, originally from North Carolina and a signer of the Constitution, had become a Senator from the newly formed state of Tennessee the previous year according to the U.S. Senate.

What happened? Blount was fond of land speculation — buying real estate up in hopes that it's someday valuable, according to Smithsonian Magazine. He had lost quite a lot of money doing this and was in dire straits. It was then that he hatched a complicated plan with British investors. He would convince Native Americans and others to attack Spanish-owned lands (which would eventually become Florida and Louisiana) to raise the value of his own lands.

Blount broke rule number one of committing crimes and wrote the whole plot down in a letter that was meant to explain the complex scheme to potential compatriots. One of these letters wound up in the hands of President John Adams, who considered it treason. Congress voted to impeach Blount and remove him from the Senate, but before he could be arrested, he fled to Tennessee. He was oddly still beloved there and was elected to their state senate shortly after.

Judge George Wythe's death was like a murder mystery

Judge George Wythe was one of the greatest legal minds of early America, and was a mentor to people like future Presidents James Monroe and Thomas Jefferson. He had signed the Declaration of Independence and was a highly praised legal and political thinker.

But one day in 1806, Wythe, his black (free) servant, and his 16-year-old pupil all took gravely ill, according to HistoryNet. All had drunk coffee with their breakfast from the same pot. While initial suspicions fell on cholera, it soon turned out that Wythe believed he was poisoned by his shiftless grand-nephew, George Wythe Sweeney. Sweeney had a habit of stealing from Wythe whenever possible. Wythe tried to reform him, but failed again and again. Finally, he threatened to cut Sweeney out of his will. What's more, Sweeney had been spotted throwing something into the coffee pot by Wythe's servant, crushing a white powder, asking about poisons, and arsenic was even found outside the window of Sweeney's cell after he was arrested.

It seemed like a slam dunk, but there was a problem. Virginia had a law on its books that black people could not testify against white people under any circumstances. It didn't matter if they were slaves or free, and the majority of the people who could testify against Sweeney (namely Wythe's household staff) were black. This left the prosecution with almost no evidence, and in the end, Sweeney was acquitted.

Richard Stockton was imprisoned and tortured by the British

Not all of the Founding Fathers were gifted politicians. Some were philosophers, writers, and yes, lawyers. Richard Stockton was the latter. He owned the largest legal practice in the colonies, and was very respected in his home state of New Jersey. He initially had no interest in politics or the burgeoning American Revolution, but as things got harder to ignore, he threw his lot in with those seeking independence, according to the Independence Hall Association.

While Stockton only dabbled in politics, briefly serving as a delegate in the Continental Congress and signing the Declaration of Independence, his heart was definitely more in the legal field, as he also served as a New Jersey Supreme Court Justice. But his brief political career cost him the most. After the British overran New Jersey in 1776, the thing that many Declaration of Independence signers feared actually happened to Stockton — he was captured by the British army.

Not only was Stockton arrested, the British also tortured him by starving him and leaving him with no heat in freezing weather. When he was eventually released, Stockton returned to his home to find that all of his possessions were either burned or stolen by British soldiers. He was left with nothing, and went back to running a legal practice to raise funds and get back on his feet. Unfortunately, he died of lip cancer just two years after his release.

Patrick Henry kept his wife in their basement

You might vaguely remember the name Patrick Henry, but you almost certainly remember his famous quote: "Give me liberty, or give me death!" Henry was a renowned orator, a signer of a lesser-known founding document of the United States, the Continental Association, and a representative for Virginia in the Continental Congress.

Henry was also a family man with six children and a wife, Sarah Shelton Henry. But all was not happy in the Henry household. After their sixth child, Sarah began to suffer from depression and violent outbursts, according to the Smithsonian Institute. She began attacking those around her, so she would often be placed in a rudimentary straitjacket. There was a psychiatric hospital in Williamsburg, VA, but Patrick wouldn't send his wife there, as he knew that it was a barbaric place that often injured or even killed patients.

Instead, Patrick had a small apartment built in the family's basement, where Sarah was locked away. Reportedly, the family did visit her often, they didn't just leave her down there, but it's hard to think of it as anything but cruel by today's standards. In 1775, after years of living this way, Sarah died. The exact cause of death is unknown, but historians speculate that she committed suicide.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).