The Truth About The Legendary Shaolin Monk Warriors

The Marvel Cinematic Universe is insanely popular, and it's no wonder — there's a superhero for everyone. Whether you'd choose super speed, super strength, or just some time-bending magic, there's someone there for you to root for.

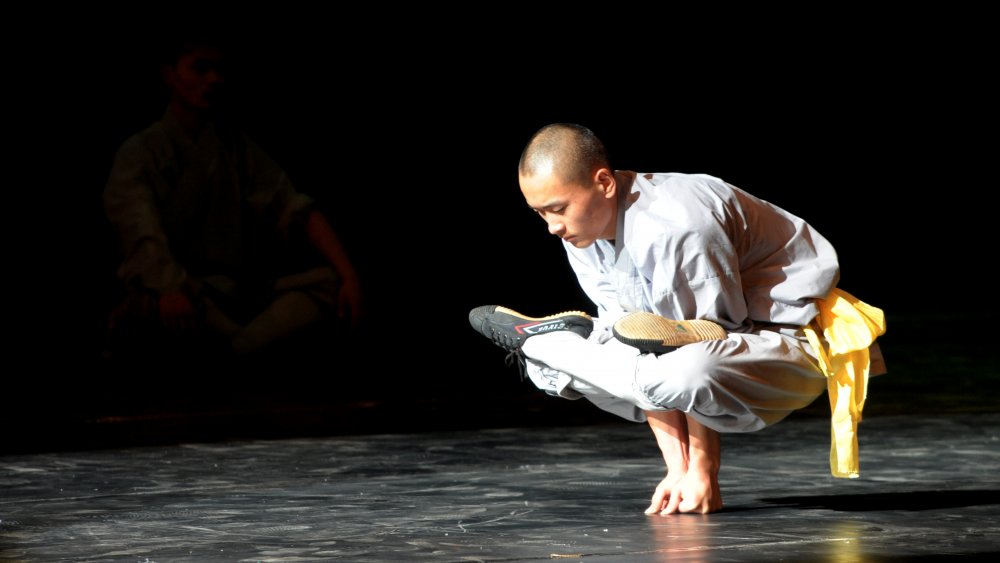

But just as everyone knows that's fiction, there are some very real warriors in the very real world that could absolutely hold their own alongside Spider-Man. Watch just a few minutes of any demonstration by the Shaolin monk warriors and you'll walk away believing in mortal man's ability to defy gravity and bend the laws of physics... if not outright break them.

They get their name from the Shaolin Temple, which sits at the base of Songshan Mountain in China's Henan Province. According to legend, an early monk found that long periods of meditation weakened the body, so he introduced martial arts as a way of strengthening the physical form alongside the spiritual one. It worked. Today, the monks are still capable of some of the most incredible feats of strength, speed, and agility that science still can't entirely explain... and it's tried.

The Shaolin temple's origin is part history, part legend

According to the Shaolin Temple's official history, they were founded in 495. To put that in perspective, that's about the same time as the fall of the Roman Empire. But when historians start going that far back in time, it's tough to tell just what is truth and what is legend — and the founding of the Shaolin order is a pretty good example of that. According to the story (via ThoughtCo.), it was around 480 that a wandering Buddhist teacher named Buddhabhadra made his way into China from India. In China he was called Batuo, and in 496, he was given funds to build a monastery, which isn't today's Shaolin Temple — the building was destroyed and rebuilt a number of times.

The temple, says The Telegraph, was always home to a monastic army — although there were patches of history where they were disbanded and forced to practice in secret, but historians can't agree on when that was. They're pretty sure they were persecuted by the Qing dynasty in the 17th or 18th centuries, and when monks fled the temple, they spread knowledge of their fighting style as they went.

But all that comes with a footnote: historians are also careful to caution that it's impossible to tell what part of the Shaolin story is history and what is folklore.

No one really knows how Shaolin Kung Fu developed

The fighting style of the Shaolin monk warriors is nothing short of incredible, and it's not entirely clear exactly how it was developed or spread. According to The Telegraph, one legend says that the movements developed from the motions used to carry out everyday chores, like gathering firewood and carrying water.

Regardless of how it was developed, today, Shaolin monks choose which of the five animal styles to specialize in (via Black Belt). The most popular are the tiger (which relies on brute force and upper body strength) and the leopard (which is defined by fast attacks targeting soft tissues, pressure points, and vital areas). Next is the crane, which is more of an evasive style, and the snake, which relies on speed and intimidation. Rarest of all is the dragon, which combines traits of the other four animals.

While there are plenty of stories about the fighting styles of the Shaolin spreading throughout the world, the truth is much more difficult to find. That, says Skeptoid, is because the Shaolin Temple was completely destroyed in 1928. Around 200 monks were killed and the entire temple was burned — including the library and their ancient texts. The texts currently available were rewritten by former masters in 1980, and that makes it difficult to say what parts of the previous 1,500 years were real... and what was embellished.

Shaolin Kung Fu is all about the breathing... and honor

The Shaolin monk warriors are mostly known for their fighting style, but their training starts out as being more about stillness. When National Geographic chronicled the final hours of a master named Yang Guiwu, they also pointed out the irony that it was his lungs that had failed first.

He had spent his life teaching students that the beginning of their practice was in the breath. Harnessing that — "breathe in through the navel, out through the nose" — was the first step in learning to control the chi, or life force. It was only when everything was in harmony — breath, heartbeat, all internal rhythms — that a student could begin to unlock the powers that remained hidden to most.

They also spoke to Hu Zhengsheng, a former student who had returned to visit his master on his deathbed. He stressed that even once instruction in fighting began, it wasn't exactly about the fighting. It was about the honor: the ideal student was respectful, willing to accept defeat and hardship with grace, and was accepting of the fact that becoming a better person required suffering, struggles, and being forged by some seriously harsh treatment.

The daily schedule of a Shaolin monk is grueling

In a 2010 interview (via the Huffington Post), Shaolin monk Sifu Wang Bo shared a bit about what daily life is like at the monastery — and it's anything but easy.

Their day begins at 5:30 in the morning, with half an hour of chanting before their breakfast: always a bean soup called eight treasures. (All their meals are vegetarian.) Then, there's another half an hour of chanting, and a 30-minute break before the day kicks off in earnest.

That's followed by two hours of training, where monks switch styles every 10 minutes. Then there's more chanting, lunch from 11:30 to 12:30, then chanting, then a two-hour break that's usually spent meditating or sleeping. There's more fighting practice from 3 to 5 p.m., and between 5 and 5:30, there's no chanting... it's a time to respect the dead. Dinner is at 5:30, and it's noodles and bread. Chanting picks up again at 6:30, and lasts for an hour. From 8 to 10 is meditation, and at 10, it's bedtime. Each and every day.

The Shaolin monks' patron saint is the great protector of Buddha

The Shaolin Temple and its monks hold one particular figure in high esteem: Vajrapani. He's not only credited with being the originator of the staff-based fighting method (which began when he fought bandits while disguised as a kitchen worker wielding a long fire poker), but he also holds the title of the Protector of Gautama Buddha Himself.

According to Buddha Weekly, Vajrapani is known as the "indestructible hand of the Buddha," so it's appropriate that he's the patron saint of an order of warrior monks. There's much more to him than just his warrior aspect, and as one of the three Bodhisattvas, he's also the embodiment of one of three necessary qualities for Enlightenment. He's the one that helps people overcome all that holds them back and stands in the way of their progress: poisons, delusions, attachments, anger, hate, jealousy, pride... the road to Enlightenment is a long and rocky one, after all, and Vajrapani is the one that embodies the power of the mind to overcome those obstacles.

Training and meditation are one and the same in Shaolin Kung Fu

Think of the practice of meditation, and most of the time, it evokes images and feelings of stillness and serenity... not fighting. But according to 34th generation fighting disciple Shifu Yan Lei (via Medium), for the Shaolin monks, meditation and fighting are one and the same.

He says: "You can't take Zen out of Shaolin. Everything we do, whether punching or running or kicking or eating is done as a meditation. We take Damo as our teacher. He founded Zen and Shaolin Martial Arts. He inspires us that it is possible to access the wisdom of our minds and we can do this through our body."

Does it sound a bit boring, being in the moment all the time, when you're doing the same thing over and over? He says that's the wrong attitude to have. It's all about being in the moment, regardless of what's going on, because "the only point of power is now. Now never returns to it. [...] The only place to be is here, now." And that's true whether you're sitting or fighting... or training on the edge of a cliff face.

Shaolin monks can do some insane things without injury... here's how

When Huck attended one of Akin Akinsiku's training sessions, they were astounded. The 35th generation Shaolin Temple disciple was training with a Qigong stick (which is a "brush" of more than 100 metal rods), a metal bar, and a brick. The training? Five days a week for 80 minutes a day, the 51-year-old would hit them... over, and over, and over. By the end, there was no bruising and no pain, thanks to a technique they call "steel jacket." He explained: "The idea of this is that you can reduce the amount of damage in combat by training your body to take impact."

Researchers from the London Science Museum and Nottingham University (via PRWeb) wanted to see just what was at work here, so — with the help of Shifu Yan Lei — they set up a series of experiments to monitor how the Shaolin master's muscle reacted to impact. They found that instead of tensing again a blow, the master's muscles became "bouncy," and essentially redirected the force of the impact back into the object hitting him.

And Shifu Yan Lei can do it because of his ability to channel his life force, or Qi. He explained: "I put my Qi or breath into my ribs. It's my breath that protects me against the blows of a brick. Without the practice of Qigong, Shaolin Steel Jacket would be impossible."

The Shaolin monks' final test is insane

Not everyone who attends the Shaolin Temple becomes a master, or even a warrior monk. According to the BBC, only about a quarter of the monks at the temple are warriors, and for those wanting to become a full warrior monk, they have to pass an insanely difficult test.

Prospective monks are tested by a panel of senior monks, and the first part of the test is in martial arts, where they need to perform a routine absolutely flawlessly. They're judged not just on their movement and their execution, but on some of the most difficult maneuvers in Shaolin teachings. Also? Their use of stillness.

Then comes the second part of the test: and examination in their knowledge of Buddhist teachings. They're required to first recite an entire passage of scripture solely from memory, and while that doesn't sound too hard in itself, there's a catch: they don't know what they'll be asked to recite, and senior monks can choose any mantra from a 200-page book of mantras.

Shaolin monks have monitored meditation progress with some high tech

Meditation has been around for a long, long time — according to Mind Works, no one's sure just how long people have been practicing it, but there are records dating back to 1500 BC that suggests it originated in India.

Modern medicine has been fascinated with what meditation does to the brain, and in 2001, the BBC reported on a study being done by New York University. They were looking at the brains of Tibetan Buddhist monks as they meditated inside an MRI machine, and found that the brains of experienced practitioners really did change. The neural network is thought to be organized into two different sections: the extrinsic is activated when we're engaged in a physical task, and the default network is activated by thoughts and emotions. In most people, either one or the other is active — think of it like a see-saw. In those who meditate a lot — like, a lot — it's possible for both networks to work simultaneously, causing that feeling of oneness monks often describe.

And according to an interview with Shifu Wang Bo (via the Huffington Post), Shaolin monks now use Western technology to monitor their meditation progress in a very concrete way. Every two weeks, they report to the hospital to have their progress measured via EEG testing — so, if you think meditation might be one part of the training you might be able to fudge a bit, you'd be sorely mistaken.

In 2007, they celebrated the return of an ancient ceremony

Very rarely, a Shaolin monk may have nine burn marks on his scalp. Those are the marks form a ritual called Jieba, and it's rare to see them because the ceremony had been banned by the Chinese government for around 300 years.

The ban was partially lifted in 2007, and according to the Huffington Post, 100 monks were invited to participate in the month-long ceremony that culminated into one of the ultimate tests of mind over matter. The ritual involves nine sticks of incense, fixed to the monk's scalp with a paste. They're left to burn for five minutes, and during those last few minutes, the incense burns to the skin. The burn marks that are left symbolize the rules of conduct that every Shaolin monk aspires to abide by: don't lie, don't drink or use drugs, don't steal, don't eat meat or kill animals, remain celibate, and don't pass judgement on others.

Shaolin monks are rarely chosen to participate in the Jieba, and of those that do, not all actually make it to the end. It's so painful that some even faint during the process, and the ritual remains incomplete. Of the first 100 monks invited to participate, only 43 completed the ritual.

Shaolin wisdom

Matthew Ahmet was a 16-year-old from London when he left to study at the temple, and he went on to return to the UK and run a branch of the temple in London. He shared some of the lessons he learned with BT, and they're lessons that everyone could stand to learn from.

Ahmet says that while he very quickly learned not to take anything for granted, he also learned that it was passions — doing what you love — that makes a person happy, not having more and more things. He also learned the importance of meditating every day, and in today's busy world, who has time to do that? But that's the thing: he says that if you take the time to stop, to embrace moments of stillness and peace, to take a break from the rush-rush-rush, you'll end up going further in life. Wake up early, meet the day head-on, and you'll have time to do that.

Because, Ahmet says, it's important to give 100 percent to each and every day. Rather than going through the days, months, and years fearing death, go through them living life. Find responsibilities, find your purpose, find goals, and find yourself. He says: "Life is as simple as a choice. ... give 100 percent and when you give 100 percent, you will get 100 percent back — that's how it works. It's karma in the most obvious way. [And] as soon as you know 'why,' there are no questions."

The Shaolin monks have female counterparts

While it's the Shaolin monk warriors that get the most attention, there's also Shaolin nuns. And they, too, can be warriors. According to an interview with the Shaolin Abbot Shi Yongxin (via the Huffington Post), there are four different groups of students: "There are male monks and there are the nuns, male house-holders who live ordinary everyday life, and female house-holders who practice. So no one is excluded." And it was always that way — while female warriors aren't a majority, the line goes back 1,500 years, and has never been broken.

In fact, one of the animal styles of fighting — the Dragon — has historically been said to have been created by a female warrior named Ng Mui. (In other lore, she's credited with partnering with a monk to adapt the movements of animals for all the animal styles of fighting in Shaolin tradition.) According to the Michigan Shaolin Wugong Temple, she's named in many stories told about Shaolin history, and while it's unclear what's history and what's legend, it's undeniable that she holds a place of respect within the temple.

Today, there are still orders of fighting nuns. In 2008, His Holiness The Gyalwang Drukpa — head of the Druk Gawa Khilwa nunnery in Nepal — decreed that in order to promote gender equality and help empower the nuns of the temple (many of whom came from poor families), they were going to get all the training the monks did (via the BBC).

Today, it's all about the bucks

The Shaolin Temple has been around for centuries, but in the 21st century, not everyone's thrilled with the way things are going. In 2015, China Daily was reporting that Abbot Shi Yongxin was on the defensive after the media wanted to know where the temple was getting the money to build cultural centers and training facilities all around the world — including a 1,200-hectare facility planned for Australia. Commercial gains aren't, after all, a very Buddhist thing, and the Abbot insisted that they were simply allowing investors to help spread their teachings.

They weren't the only ones questioning. The Global Times suggested that "business practices undermine temples' holy purpose," while Skeptoid went a few steps farther with: "Just about everything you think you know about the Shaolin Monks was made up for tourists."

The Western world really did get their first introduction to the Shaolin order with David Carradine and Kung Fu, and you can't get much more commercialized than that. Sure, you can watch live stage shows, and sure, the temple licenses its name to just about every product under the sun, but does that undermine the hard work and the capabilities of its monks? That's up to the individual to decide.