False Things You Believe About Walt Disney

How many businessmen and corporation founders are known by their first and last name by billions of people? And how many people start off as humble artists and go on to start one of the most influential, powerful, and profitable companies in the world? Not too many — and Walt Disney is probably the only person in both categories.

The Walt Disney story is a classic, only-in-America, 20th-century success story. He rose from artist in a Midwestern ad agency to become an animator, filmmaker, theme park builder, studio boss, tastemaker, and creator and defender of wholesome family entertainment. Walt Disney is certainly legendary, but with such larger than life and deeply important figures (the man made animated feature films a thing with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and amusement parks classy and magical with Disneyland), they're often prone to — or guilty of — some major myth-building. Much of what we believe about Disney — a man so beloved that his nickname is "Uncle Walt" — is just plain false. Let's set the record straight.

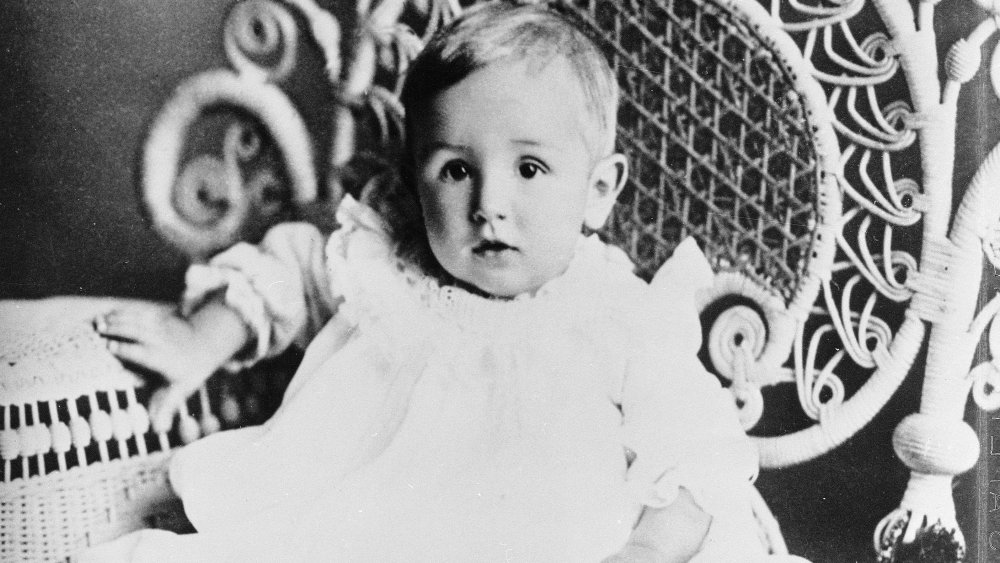

Walt Disney was born in the small town of Robinson, Illinois

Emblematic of virtues like entrepreneurship and hard work, Walt Disney has an origin story that's well-known, inspiring, and as all-American as baseball, apple pie, and exorbitant amusement park ticket prices. Disney's career started in earnest as an artist at an advertising agency in Kansas City, where his family had moved when Walt was nine years old. Before he moved to that Midwestern metropolis, Disney spent his early childhood in the perfectly small and idyllic small town of Robinson, Illinois. See, while trying to earn enough money to reach Chicago, Disney's parents temporarily settled in Robinson, where Mr. Disney found a job with a man named George Walter, who also rented the couple a room. Soon thereafter, Walt Disney was born, named for his father's generous boss.

However, according to Snopes, all of that is bogus. Those details come from a story proudly published in the Robinson Argus in 1982, based on the unreliable recollections of an elderly local resident. In reality, by the time of Walt Disney's birth in 1901, his parents were living in Chicago and had three other children, one of whom they nearly named Walter. Disney was actually born in Chicago, and he wasn't named after some guy who gave a job and an apartment to his dad.

Walt Disney created Mickey Mouse

Walt Disney is synonymous with Mickey Mouse, a character so successful that it led to a major animation studio, an entertainment conglomerate, and chain of theme parks, all linked by the squeaky-voiced little guy. He's the company's smiling mascot and a merchandising machine. All of this was meant to be, implied by the official Disney line that Walt Disney came up with Mickey during a train trip in 1928 when his attempts to break into the entertainment business were woefully failing.

However, according to Jeff Ryan, author of A Mouse Divided (via the New York Post), Walt Disney didn't invent the Mickey Mouse character, nor draw him for the first time — Ub Iwerks did. Disney first connected with Iwerks while both were working as artists in Kansas City in 1919, ultimately forming their cartoon studio. In the late 1920s, a bad business deal led to the loss of their moderately successful character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. So they got to work, and Iwerks drew some cartoony images of a cow, horse, dog, and frog. Disney didn't like any of them and suggested Iwerks draw a mouse.

Before long, Iwerks had developed the basic design of the character that would come to be known as Mickey Mouse. After Disney and Iwerks' creative partnership later dissolved in a non-amicable way, Disney started telling a false tale about how he'd created Mickey on a train, leaving Iwerks completely out of the story.

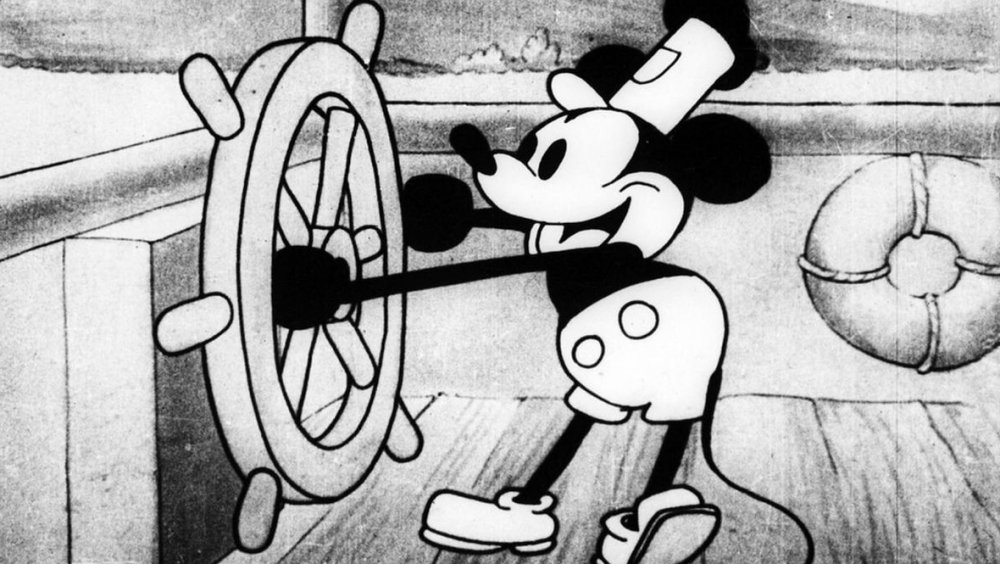

'Steamboat Willie' was a landmark in animation

Of all of the hundreds of short cartoons produced in the early 20th century, it's the characters featured in them that are famous — Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Tom and Jerry. Very few individual cartoon titles are memorable, with the exception of landmark classics like 1928's "Steamboat Willie." It's a household name, with common knowledge holding that it was pioneering in many ways. For example, it's said that "Steamboat Willie" is the first Disney cartoon, the first cartoon starring the immensely famous Mickey Mouse, and the first cartoon with sound. The Disney company considers the toon such a turning point that it's got a spot in Disneyland where it plays on a loop all day.

However, most of what the public thinks about "Steamboat Willie" isn't true. It's not the first cartoon Walt Disney made. According to The New York Times, in 1921, Disney founded the animation studio Laugh-O-Gram, and he produced short, cartoon takes on fairy tales like "Puss in Boots" and "Red Riding Hood." However, the studio went bankrupt, and in 1923, Disney moved to Hollywood and directed 50 cartoons featuring Alice from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. And he only started making Mickey Mouse cartoons after creating another character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit.

And believe it or not, the first cartoon featuring ol' Mickey was "Plane Crazy," a silent film that was produced in 1928 but wasn't released until 1929. "Steamboat Willie" was pioneering only in that it was specifically the first cartoon starring Mickey Mouse with a synchronized soundtrack.

Walt Disney was openly anti-Semitic

The 1994 Simpsons episode "Itchy & Scratchy Land" is full of jokes at the expense of all things Disney. Bart and Lisa see a brief film about Itchy & Scratchy creator Roger Meyers Sr., a Walt Disney stand-in whose cartoons include "Steamboat Itchy" and "Nazi Supermen Are Our Superiors." That's a nod to the idea that Disney hated Jewish people, a notion supported by a speech Meryl Streep delivered at the 2014 National Board of Review Awards where she said the man "formed and supported an anti-Semitic lobbying group."

This may all stem from a 1938 incident in which Disney gave a personal tour of his production studio to Leni Riefenstahl — official film documentarian of Hitler's Third Reich — a tour which came just a month after Kristallnacht, the Nazi-organized terrorist attack that destroyed synagogues and Jewish-owned businesses and left nearly 100 Jewish people dead.

Disney turned down Riefenstahl's efforts to return the favor by showing him her films of the 1936 Olympics held in Germany, but the association with the Nazis forever tarnished his reputation. However, Neal Gabler, who wrote Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination and claims to have read all of Disney's personal papers, says there's little proof of any virulent Jewish hatred on Disney's part. "I saw no evidence, other than casual anti-Semitism that virtually every gentile at that time would have, that Walt Disney was an anti-Semite," he told USA Today.

Walt Disney worked hard for his Oscars

Walt Disney is a majorly formative figure in the motion picture industry and in how films are produced, presented, marketed, and managed. Disney's company churned out volumes of content from the 1930s to the 1960s — not just classic animated features but also many short films, both animated and live-action. Disney absolutely dominated the world of shorts, and as such, routinely received Academy Award nominations in the appropriate categories. For example, between 1932 and 1963, Walt Disney was nominated for Best Short Subject, Cartoons an astounding 38 times. Not counting four special and honorary awards, Disney took home 22 Academy Award statuettes overall, making him the most individually honored person in Oscars history.

But this is all a function of how the awards are distributed, not necessarily Disney's prowess as a filmmaker. In many Academy Awards categories, it's the producer who gets to take home the trophy — the person who put up the cash, made the phone calls, and organized things, not the people capturing the footage, sitting in the editing bay, or writing the script. Walt Disney, because he controlled the company and approved all those Oscar-winning shorts, got to stake a claim to the hardware. Take Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day, which won the Oscar for Best Short Subject, Cartoons in 1969. Disney, the credited producer and thus recipient of the trophy, couldn't have been all that active on the project, considering he died in 1966.

The mother is often dead in Disney movies because he felt guilt over his mother's death

There's a unique but dark element that recurs throughout Disney's kid-friendly animated features: The main character is motherless, either having lost their mom by the time the events of the movie begin or during the film itself. Among the classic Disney movies with a mom-less protagonist, we've got Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast, The Jungle Book, Bambi, and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. According to Hollywood lore, there's a sad reason behind a plot line so common that it feels like a Disney directive. As the story goes, Walt Disney's mother, Flora, died in 1938 after suffering carbon monoxide poisoning from an improperly working furnace in her brand new home. Because he'd bought the house, Disney blamed himself for his mother's death, and the guilt led him to make movies about motherless figures.

The connection is weak, at best. Many Disney features are based on pre-existing and seriously dark children's books and fairy tales, where dead moms are a common factor. It's a powerful literary device that can characterize a protagonist as a sympathetic underdog. Besides, as Snopes points out, Disney's mother died after the pattern of semi-orphaned Disney characters had been established. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs hit theaters a year before Flora Disney's death, while Bambi (featuring the traumatizing death of Bambi's mom by a hunter's bullet) was in production at the time of the Disney family tragedy.

The Disney logo is Walt Disney's signature

The logo for the Walt Disney Company — along with variations for different branches of the wide-reaching corporate conglomerate, such as Walt Disney Studios — is one of the most famous in the world. After all, the logo is a signature, that of Walt Disney, the company's founder, boss, and creative guide for many decades. Using a signature of a person is also a savvy bit of branding genius. It implies that anything bearing the Disney name (and logo) is essentially handcrafted, with the legendary boss personally signing off on it.

Well ... that's the commonly believed story.

But believe it or not, that famous signature wasn't actually what Walt Disney's handwritten name looked like. As he was a very busy man, assistants and aides were authorized to sign Disney's name, leading to a disparate variety of historical examples of the man's so-called penmanship. And Disney himself adapted and evolved his own signature over the years, introducing more confusion into the mix. At any rate, the signature used as the Disney logo is a highly stylized version of the way that Disney wrote his name in the 1940s ... and it wasn't introduced as the company's logo until 1984, nearly two decades after the founder of the operation died.

Building Disneyland capped a wildly lucrative career

Disneyland opened in July 1955, and like virtually every day since, the park was jam-packed on day one, with about 20,000 guests. Within a few weeks, more than a million people had visited. It was a rousing success, leading the world to forget about all the pre-opening troubles and skepticism that Walt Disney faced.

However, Disneyland wasn't some crowning achievement after a successful career making animated blockbusters. In fact, in the early 1950s, Disney didn't necessarily have the universally known and loved brands yet to make a theme park work. And besides, the perception of amusement parks at the time was that they were dirty, dangerous, and low-class. But according to American Heritage, Walt Disney was so desperate to create Disneyland and so convinced that his unique vision would be successful that he took out a loan against a life insurance policy to fund the planning. He supposedly only had around $1,000 in the bank at the time.

To further bolster the coffers for the Disneyland project, Walt Disney turned to television. While other movie studios saw TV as a competition and a threat, Disney embraced the medium, authorizing a weekly showcase of Disney films and cartoons on ABC called Disneyland. Disney hosted the show himself, where he also gave updates on the building of the Disneyland park. In other words, these were ads, which got the public very psyched by July 1955.

Walt Disney was kind and understanding to P.L. Travers

The 2013 film Saving Mr. Banks details Walt Disney's personal wooing of author P.L. Travers to adapt her Mary Poppins books into what would become a beloved, Oscar-winning movie musical. Emma Thompson portrays Travers as a curmudgeonly grump who holds on tenaciously to her intellectual property, and she refuses to let Disney make anything treacly or sentimental out of her books because they're actually a cathartic celebration and eulogy for her troubled father. And beloved Hollywood nice guy of yore, Walt Disney, is played by beloved Hollywood nice guy of today, Tom Hanks. The legendary actor portrays the executive as endlessly patient and empathetic, and he convinces Travers to sign over the movie rights after he tells her that he had a a similarly bad childhood.

However, according to Saving Mr. Banks screenwriter Kelly Marcel (via Screen Crave), Disney already had the film rights to Poppins before Travers flew in to California to consult on the script. And Disney historian Jim Korkis (via Orlando Weekly) noted that it's highly unlikely that Disney and Travers discussed their younger, more troubled days, especially since Disney didn't think he'd had a troubled youth. And in real life, Travers proved so combative that Disney didn't pop in on her progress the way he does in the movie. "Walt Disney got fed up after the first day and went to his vacation home in Palm Springs," Korkis said. And even though Travers ends up liking Mary Poppins in the 2013 movie, in real life, she hated Disney's adaptation.

The dead body of Walt Disney was cryogenically frozen

In December 1966, after suffering from lung cancer, 65-year-old Walt Disney died ... but only for the time being, according to one of the most bizarre and persistent myths to ever circulate. Disney was keenly and publicly fascinated with futuristic, utopian technology, as evidenced by the "Tomorrowland" section and use of animatronics at Disneyland. That interest in what the future offered also transpired in an interest in cryogenic storage — the act of freezing a dead body (or just a head) at subzero temperatures to be thawed out later and restored to life. Well, when the technology to do that is perfected, of course. Thus, there's this urban legend that Disney had his body or head placed in an extremely cold chamber in a secure facility immediately after his death.

The rumor likely originated from statements made in 1972 by Bob Nelson, president of the pioneering California Cryogenics Society (CCS), who claimed that Disney had shown at least an intellectual interest in cryogenic freezing, but that he died before he could make any stipulations in his will telling his family to put his body under ice. Also helping to spread this fake news? The CCS froze its first subject just two weeks after the death of Disney. But as for the animation legend himself, his remains were cremated and interred after a secret, private funeral for just his family.