Famous Historical Figures Who Were Quarantined

Even before the events of early 2020, the concept of quarantine — staying at home and avoiding people, especially crowds, to limit the spread of a disease — might have sounded familiar if you'd paid attention to any zombie movie ever.

But in real life, quarantine is a scary idea, especially when you don't know when it will end. You sit and while away the days, probably watching said zombie movies on Netflix. But isolating oneself from an illness is hardly a new idea. Throughout history, cities, countries, and even entire regions have been locked off (forcibly, in most cases) until the disease has run its course.

And some of the people affected by these quarantines were famous. Maybe they got locked down with everyone else. Maybe they used their power and resources to flee elsewhere. The point is, they had to upend their lives, too, and didn't even have Netflix.

Shakespeare may have written King Lear during a quarantine

While the infamous Black Death is the most familiar outbreak of bubonic plague in Europe, it was far from the only one. England alone suffered numerous resurgences of the plague over the centuries, including one particularly bad outbreak in 1606, the height of popularity for a prolific playwright by the name of William Shakespeare.

While London was familiar with plague outbreaks, often allowing theaters to stay open if only 40 people or less had died the previous week, this particular epidemic was killing two or three times that, effectively ending the theater season for 1606, according to The Guardian. Shakespeare was fortunate his particular neighborhood in London was largely untouched by the plague until late in 1606, but it's likely he had already been self-isolating since the city's theaters had closed.

While we don't know exactly what Shakespeare got up to while avoiding the death around him, historians speculate he wrote King Lear, which premiered just before the end of 1606, and possibly others as well, such as Macbeth, during this time. These two, King Lear especially, were some of Shakespeare's darkest plays, and so it's very possible he wrote them in isolation with the plague surrounding him. If that wasn't enough to inspire plays filled with death and tragedy, then it's hard to imagine what might have.

Isaac Newton laid the foundations for calculus while in isolation

England's Great Plague of 1665 was one of the last major outbreaks of bubonic plague in the country after centuries of the disease coming and going in waves. By this point, the British were all too familiar with the plague and strategies for combating it, which included, yes, social distancing. Much like schools in 2020, historical colleges of the time ended their school years early and sent students home to wait out the spread of disease, according to the Washington Post.

One young student of Trinity College in Cambridge was named Isaac Newton. He was in his early 20s, and still had a long way to go before he could put "Sir" in front of his name. When the school shut down over plague concerns, he went home to his family estate, where he spent a year studying alone. And while a great many people prefer the social aspects of education with teachers and fellow students, Newton actually did very well self-studying and learning on his own.

Newton wrote papers that would eventually lead to the invention of calculus, experimented with light and optics, and allegedly witnessed an apple falling from a tree in his yard, which would eventually lead to his theories on gravity. Newton came back to school in 1667 and his academic career skyrocketed afterward. Too bad quarantine doesn't make everyone this productive.

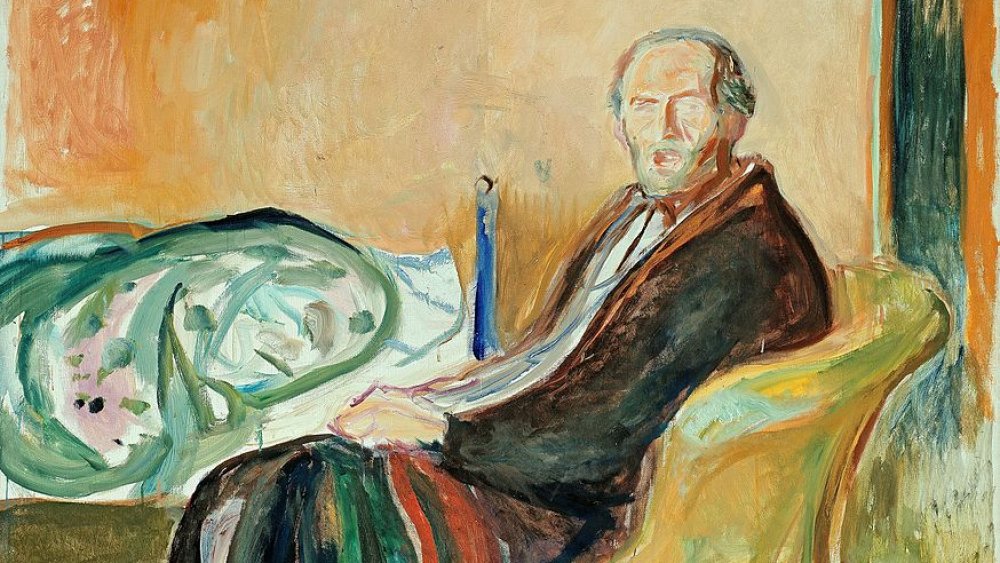

Edvard Munch kept painting while suffering from Spanish Flu

Edvard Munch is most famous for painting the creepy and surreal The Scream, but the fact is, Munch painted a lot of spooky pieces that evoke feelings of isolation or anxiety. That might have something to do with the fact that, at a young age, little Edvard's mother and sister succumbed to tuberculosis, according to Artists Network. Another sister was diagnosed with a mental illness, leaving Munch to feel, well, isolated and anxious.

Often sickly himself, Munch turned to painting as his outlet, and his haunting style quickly drew a lot of attention. However, on a personal level, Munch continued to primarily keep to himself, and he earned a reputation for being a bit of a hermit or loner. Much of his art focused on his own internal suffering and a sort of vague dread of being around other people.

And then, in 1918, Munch came down with the so-called Spanish Flu, which was experiencing a global pandemic at the time. Since Munch already preferred his own company, it didn't take much for him to self-quarantine. One of Munch's most common subjects was himself, and he created two self-portraits during this time. One, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu (pictured), features Munch sitting alone, wrapped in a dressing gown and looking miserable. Once he recovered, he painted a follow-up, Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu, where he appears well-dressed and in much better spirits.

The Apollo 11 astronauts were quarantined for three weeks

One of the greatest scientific and technical achievements of the 20th century, putting actual humans on the surface of the moon for the first time in history, had a bit of a secret drama going on behind the scenes. The astronauts were quarantined before launch, mostly to make sure they didn't bring any Earth bugs with them, which could have caused the mission to require a whole lot more cough medicine. They even had to turn down dinner with President Richard Nixon because of this, according to Space.com.

But the weird part is what happened after they touched down on the lunar surface. You see, while NASA scientists thought it highly unlikely, there was a remote possibility the astronauts could pick up some sort of moon plague and bring it back to Earth. It sounds ridiculous now, but it was very much a case of "better safe than sorry." From the moment the astronauts lifted off from the moon, a three week counter began in which they'd be quarantined. This included the trip back, but they still had about two weeks of quarantine on Earth even after splashdown.

What's more, NASA required them to wear odd containment suits a diver tossed into the capsule for them and keep them on until they could be brought back to NASA HQ, where they were isolated until medical experts were 100 percent sure the space flu wasn't going to kill everyone on the planet.

Typhoid Mary spent much of her life in quarantine

Mary Mallon emigrated from Ireland to New York City in around 1884. She soon discovered her calling as a cook. Things were going fairly well for Mary, at least until people started getting sick around her. Mary herself felt fine, though, and she continued to cook for several years before the New York City Health Department figured out she was an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever, according to PBS.

While most of this article is about famous people who ended up in quarantine, Mary Mallon is famous because she was quarantined. She became known as Typhoid Mary, and insisted she had done nothing wrong and wasn't sick, stubbornly continuing to work in food service until city officials arrested her in 1907 to limit the spread of disease. They gave her a choice between having her gallbladder (where typhus germs collect) surgically removed, or forced quarantine. Mary chose the latter and stayed isolated until 1910, when officials thought the danger was over and Mary could go free. But she could never work in food service again, to which she agreed.

Needing extra money, though, Mallon returned to cooking a few years later. When cases of typhoid fever shot up again, authorities immediately suspected Typhoid Mary and arrested her again in 1915. This time, they gave her no choice. She was quarantined on North Brother Island off the coast of New York City for the rest of her life.

Mary Shelley created a monster while isolated

In May of 1816, the world was a darker place, literally. In 1815, Mt. Tambora in Indonesia underwent one of the deadliest volcanic eruptions in history. It didn't just kill those nearby, though. The dust and ash polluted the air so badly it threw off growing seasons, which led to cold and famine all the way in England. The conditions were ripe for a cholera epidemic that began to rip through the world, as well, according to History.

Mary Shelley and her new husband, Percy Bysse Shelley, decided to get away from it all, along with Mary's step-sister, Claire Clairmont, and Percy's doctor, John Polidori. They traveled to Lake Geneva in Switzerland. There, they ran into fellow writer (and Clairmont's erstwhile lover) Lord Byron. While the trip started off as an escape from the troubles of the world, it turned out things weren't any better in Switzerland, so bad weather and illness kept them inside their rented mansion for the most part.

It was during this period the group, after spending dreary days reading horror stories, decided to try to write their own scary tales. Mary Shelley's novel, Frankenstein, was birthed from this trip, and it ended up becoming a massively influential creation on horror, sci-fi, and literature as a whole. What's more, Dr. Polidori's novella "The Vampyre" was also created at Lake Geneva, and it was one of the earlier examples of vampire fiction in the English language.

Giovanni Boccaccio based The Decameron on his quarantine

The Black Death is typically estimated to have killed somewhere around one quarter of all Europeans. It was easily one of the deadliest epidemics to threaten mankind, and a great many writers lived through it, giving us many primary sources about the disease. One piece in particular, though, The Decameron, while not about the plague specifically, is considered not just one of the greatest pieces of writing to come out of the Black Death, but one of the greatest pieces of literature, period.

Written by Giovanni Boccaccio, the book is set in Florence during the Black Death and features 100 stories — 10 stories each told over 100 days. While Boccaccio only directly commented on the plague in the book's prologue, describing people dropping dead in the streets according to The New Yorker, the book's premise is clearly based on Boccaccio's experiences during the Black Death. It features 10 people, seven women and three men, avoiding an unnamed plague in a secluded villa and telling stories to pass the time.

It's not clear if Boccaccio had this exact experience, but he definitely spent some time isolating himself from the disease, like most survivors. While the stories themselves only occasionally reference the devastation going on around the characters, the theme of death permeates the entire work, as noted by Brown University. It's a tome about an outbreak and the things people will do in order to survive.

The entire US federal government fled from yellow fever

In 1793, the fledgling United States of America had set up its temporary capital in Philadelphia, PA. The spot made sense, as it was more or less centrally located in the territories the newborn country claimed and it was the city where the Declaration of Independence was signed. The government had already selected its permanent capital, the land that would become Washington, D.C., but it was undergoing construction and wouldn't be ready until its completion in 1800. President Washington had just wrapped up his first term and began his second when disaster hit Philadelphia.

A yellow fever outbreak struck the city of brotherly love in the summer of 1793 and lasted until fall. All told, 5,000 people died, according to History, which may not sound like a lot, but considering how much smaller the population of Philadelphia was back then, it was actually a sizable portion of the population. Once the epidemic hit, the federal government made a wise decision and left Philadelphia as quickly as possible.

With their lives flipped, turned upside-down, the government relocated from Philly not to Bel Air, which didn't exist yet, but to Germantown, PA, where they set up a temporary capital to replace their temporary capital, according to the Independence Hall Association. They stayed until the yellow fever outbreak had run its course, but apparently, Washington liked it there so much he returned for a vacation a year later.

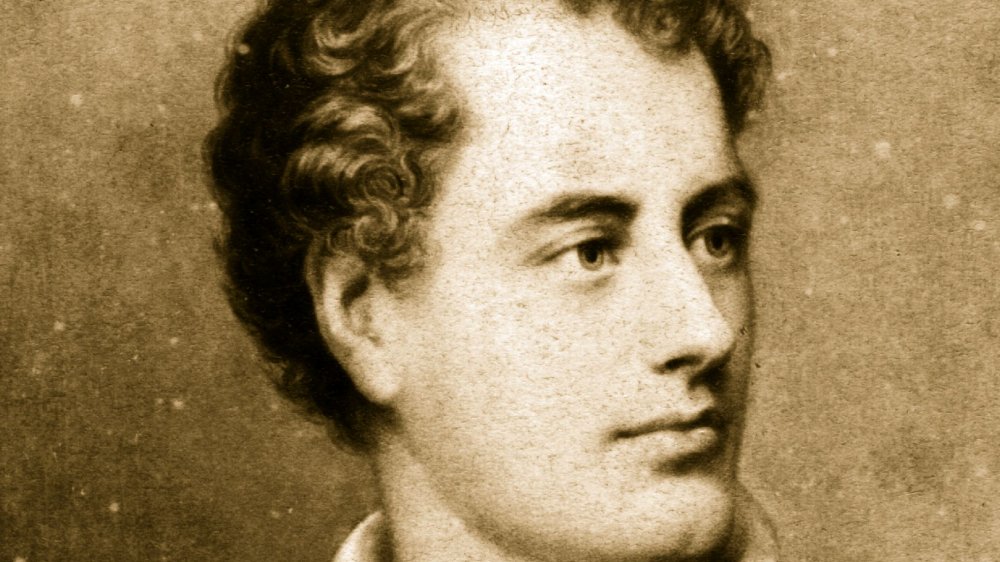

Lord Byron had an earlier quarantine experience

Lord Byron's seclusion at Lake Geneva, Switzerland with the Shelleys in 1816 was actually not his first time in quarantine. Byron was not only a talented writer, but also an experienced traveler and politician. He famously visited all corners of Europe throughout his short life (he died at age 36), and during his travels, he kept up correspondence with his friends, including fellow poet Thomas Moore.

It is from these letters we get a first-hand account of Byron's time in quarantine during the 1813 bubonic plague outbreak in Malta, where he was visiting. The plague hit Malta very hard, and due to poor leadership and unpreparedness, the island suffered greatly, according to War on the Rocks. Thus, all visitors coming into Malta were forced into quarantine to make sure they didn't bring disease with them. This included Lord Byron himself, for "forty or sixty days," according to one of his letters.

In typical Byronic fashion, he jokes he probably would have spent his time foolishly, quarantine or no quarantine, and also mentions the town he came to port in was "empty." Having a reputation for partying, this was obviously not pleasant for him. In the letter, he muses about leaving for somewhere north, but complains he needs a hot sun and cool sherbet anywhere he goes.

Sir Walter Scott was also quarantined in Malta

Lord Byron wasn't the only famous person to get stuck in a Maltese quarantine. He wasn't even the only writer. In 1831, Scottish author of books like Ivanhoe and Rob Roy, Sir Walter Scott was travelling through Malta and keeping a diary, coincidentally enough, because Lord Byron's memoirs had been so popular, and so we once again get to hear about the nature of this quarantine straight from the horse's mouth. Instead of bubonic plague this time, it was a cholera epidemic the quarantine was meant to quell.

Scott, who had grown ill in his old age (he would die about a year later), was visiting the Mediterranean in hopes of improving his health. While there, he wrote one of his final novels, The Siege of Malta, which would only be published after his death, based on his time on the island. Upon arriving at port, Scott, his family, and the ship's crew were immediately subjected to a 10-day quarantine.

Scott remarks in his diary he saw a man fall off a boat by accident, and when a passing English ship offered aid to the sailor, they were also forced to undergo quarantine by the Maltese government. Scott called it "the Maltese custom of rewarding humanity." Instead of staying at a lazaretto (a sort of quarantine hospital), Scott and his family were provided with special apartments in which they could spend their time.

A future British Prime Minister got quarantined in Malta, too

In 1831, a young author named Benjamin Disraeli set out to explore Europe with his sister's fiancee, William Meredith. Now how many people are willing to do that? The trip lasted over a year, but was cut short when Meredith died of smallpox. Disraeli opted to return home after this incident to be with his sister during her mourning, but was detained for a month in the exact same Maltese quarantine Sir Walter Scott had encountered.

Their isolation didn't overlap, however — Disraeli arrived a few months before Scott, in September 1831. While he didn't keep a diary or write prolific letters like Lord Byron and Scott, we do know a bit about Disraeli's experiences due to a semi-autobiographical novel he wrote during the trip, Contarini Fleming, wherein the protagonist is quarantined in Ancona, a city on the mainland of Italy a few hundred miles to the north. According to historian Donald Sultana, it seems the whole event could best be described as "tedious."

Disraeli did make it back home, though, and while he continued his authorship, it turns out his passion would become more geared toward politics. A few years later, he became a Member of Parliament, and eventually worked his way up to being Prime Minister from 1874 to 1880. He continued to write novels the whole time.

King Charles II and his court fled the Great Plague

When the early U.S. federal government fled Philadelphia to avoid yellow fever, it seems they might have been taking inspiration from their recent enemies, the English. During a resurgence of the bubonic plague known as "The Great Plague" in 1665, King Charles II and his entire court actually packed up that October and moved to Salisbury instead.

What's more, upon arriving in Salisbury, the plague had already begun to spread there as well. Before too long, they were on the move again, where they relocated to Oxford. During this time, Charles II tried as best he could to manage England's affairs from the road, according to James Lessor's The Plague and the Fire. He wrote to city magistrates imploring them to make sure nothing and no one went into or out of London to try to limit the plague's spread. Unfortunately, by this point, the damage was already done and the disease had taken a thorough hold.

Charles II and his court stayed in Oxford until February 1666, when the outbreak receded once again, at which point they finally made their way back to London. Amazingly enough, Parliament had even begun to hold sessions in Oxford just before finally making their way back alongside the King.