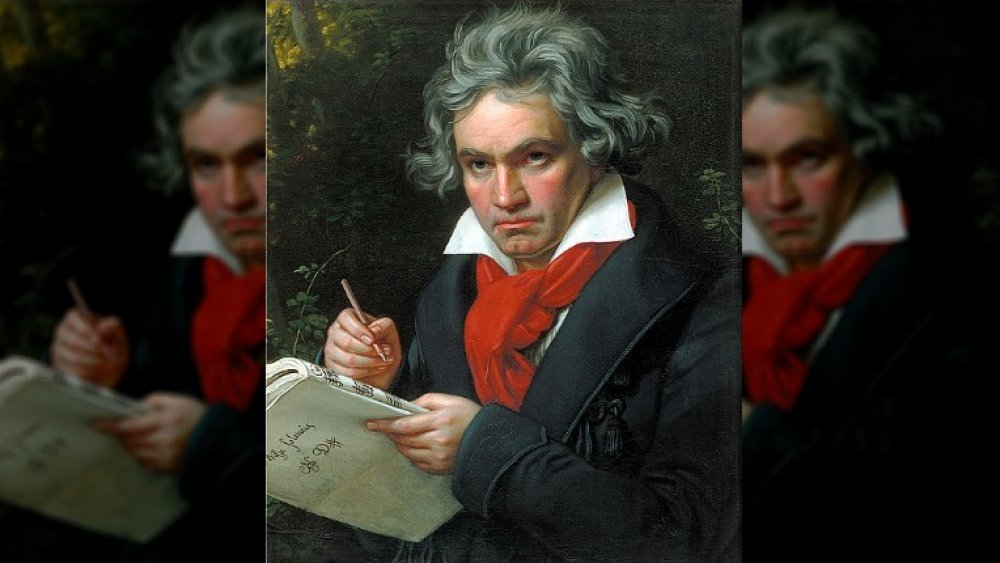

The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Beethoven

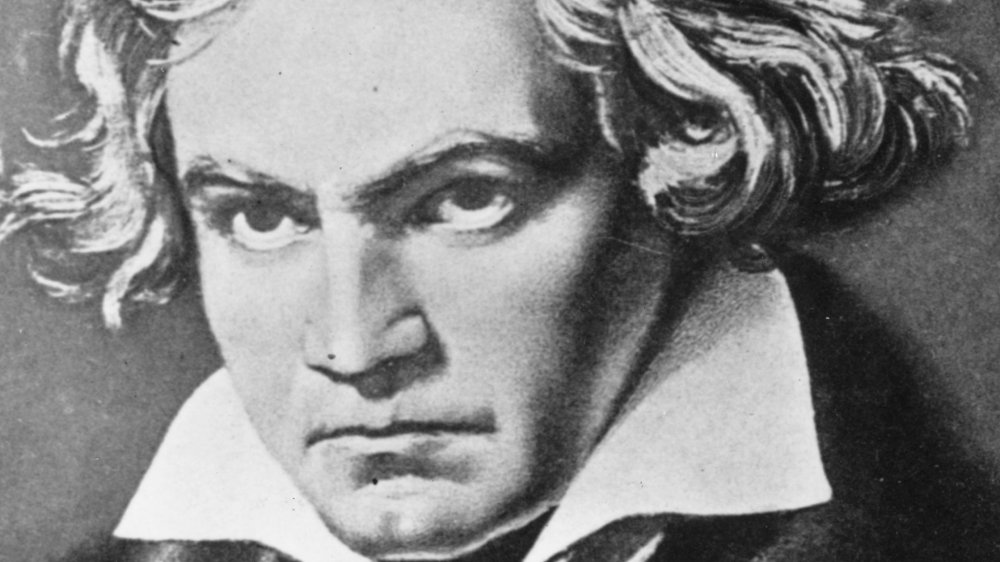

Ludwig van Beethoven is famous. He's so famous that even people who've never listened to classical music in their lives know his name. And the first four notes of his famous Fifth Symphony make up the most famous musical motif in history (come on, you totally know the notes). It might be hard for modern audiences to appreciate just how revolutionary Beethoven's work was in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Prior to Beethoven, music was usually seen as simply a framework for written works such as opera. Beethoven's complex, emotionally-charged symphonies changed that forever, proving that music alone could be an incredibly powerful and artistic experience.

While his intense persona has endured throughout the years and kept his name in the zeitgeist, even passionate fans of his work usually don't know that his life was filled with tragedy and sorrow — tragedy and sorrow that directly influenced his music, fueling the drama, the emotion, and the sheer energy that it's rightfully famous for. Here are some of the unhappy details of the tragic real-life story of Beethoven.

Four of Beethoven's siblings died as infants

Infant mortality rates were horrifyingly high in the past. Actually, morality rates in general were pretty high, with most people born around the year 1800 lucky to make it past the age of 40. Beethoven was born in 1770 and made it to age 56, so he beat those odds ... but most of his siblings didn't.

As musician, composer, and writer Georgina St George writes, Beethoven was the second child of seven born to Johann van Beethoven and Maria Magdalena Keverich. But only three of the Beethoven children survived to adulthood — Kaspar Anton Karl and Nikolaus Johann, both younger than their brother Ludwig. Beethoven's other siblings weren't so lucky. Older brother Ludwig Maria lived just six days, sister Anna Maria Francisca died just a few months old, brother Franz Georg died at the age of two, and sister Maria Margarita Josepha died aged one in 1786. For an extra dose of tragedy, that very same year, Beethoven's mother died, likely of consumption (a generic term for any "wasting disease," likely tuberculosis). Even during an era marked by so much death, this was a devastating series of losses for a sensitive, artistic young man like Beethoven.

Beethoven was probably dyslexic

Although the learning disorder wasn't clinically identified until long after his death, it's very likely that Beethoven suffered from dyslexia. Beethoven's education was cut tragically short when his mother died in 1786. And at the age of 16, the future musical legend was forced to drop out of his schooling and take over the running of the household because his father, Johann, was sinking into alcoholism and his younger brothers needed to be cared for. That crippled his formal learning, but it goes much deeper than that.

As writer Edmund Morris noted in his biography of the composer (via NPR), despite Beethoven's precise and complex musical arrangements he "couldn't multiply and couldn't divide. And he frequently transposed digits when he was writing the date." He also reportedly had trouble spelling. While it's impossible to diagnose someone from scraps of biographical detail and anecdotal evidence, most biographers suspect Beethoven suffered from some sort of learning disability, which is doubly tragic because these conditions weren't recognized at the time. Even in his musical studies, Beethoven had to fight against the impression that he wasn't very bright. Dr. Christopher Neck relates that one of Beethoven's early teachers said, "As a composer, he is hopeless."

His father was awful.

Ludwig van Beethoven was born into a family with a musical legacy. His grandfather, also named Ludwig, was an accomplished singer and was appointed court Kapellmeister (kind of like a music director) in their hometown of Bonn — a fairly prestigious position. And his father, Johann, possessed a fine voice as a young man and secured his own spot as a court musician, as well as working as a music teacher. But Johann was also an alcoholic, an affliction that slowly robbed him of his voice and his social standing, making it difficult for him to earn a living.

According to writer Kevin Martin, when Johann realized that young Ludwig had a genius for music, he thought of the success the Mozarts had enjoyed parading young Wolfgang around Europe, and he took over his son's musical education and attempted to replicate that success. He was a harsh teacher who dragged his son from sleep late at night to drunkenly demand he play for his friends, he frequently beat his son when his playing wasn't up to his standards, and he rarely, if ever, praised his son for his achievements. As he grew older, his drinking worsened, and after his wife died he became almost completely unreliable ... but certainly no less awful.

He had to raise his brothers

When Beethoven's mother died in 1787 of what was probably tuberculosis, the family was in dire straits. Beethoven's two brothers, Kaspar and Nikolaus, were too young to be on their own, but his father, Johann, was rapidly sinking into full-blown alcoholism. The loss of his mother hurt Beethoven deeply (writer and historian Jim Powell notes that the young composer wrote of her, "She was such a good loving mother, my best friend!"), but he had little time for mourning, because he had to return home and become head of the household.

This meant he had to put his education on hold. He'd been attending lectures at the University of Bonn, but that all had to stop because Johann couldn't be relied upon to provide and income for the family or to take any interest in the younger boys. Beethoven was forced to give private music lessons to anyone who would hire him simply to put food on the table. This set a pattern for the rest of Beethoven's life, as he would always try to protect his brothers (and even their children), which usually took the form of trying to control them and dictate their behavior, all while pouring his own time and money into their care.

Beethoven was incredibly unlucky in love

Beethoven never married, but he was a passionate man who had many intense connections with women throughout his life. According to The Guardian, Beethoven always found himself attracted to women he couldn't be with, usually because of their marital status or class divisions. Several of these women returned Beethoven's affections in equally passionate terms. The aristocratic Josephine von Brunsvik considered walking away from her posh life to be with him, but fears of losing custody of her children stopped her.

But nothing could be more tragic than the famous "Immortal Beloved" letter, found after Beethoven's death, in which he begged an unidentified woman to meet with him, agonizing over the distance between them and wondering how he would live without her. The identity of Immortal Beloved has never been proved (though Beethoven expert Virginia Oakley Beahrs has made a strong case that it must've been Josephine), leaving this as the sad epilogue to the lonely life of one of the world's greatest composers. At the same time, many of Beethoven's greatest works are believed to have been inspired by his rocky love life. For example, his famous work "Für Elise" is believed to have been inspired by his unrequited love for a woman named Amalie Sebald. If only he could've written great music and been happy.

Beethoven probably fathered a disabled son

Beethoven clearly used his tumultuous personal life — a life filled with unrequited love, tragic loss, and personal challenges — to fuel his creativity. That life might've been more tumultuous and tragic than we know, if Beethoven scholar Susan Lund is correct. She believes (via The Guardian) that Beethoven fathered an illegitimate child with a woman named Antonie Brentano (pictured), and that his inability to be part of the boy's life inspired some of his most powerful and emotional work.

Lund argues that Brentano was the subject of Beethoven's famous "Immortal Beloved" letter, in which the composer poured out a passionate love for an unnamed woman he couldn't be with. Brentano was locked in a loveless marriage to a wealthy aristocrat, and the year after that letter's composition, 1813, she gave birth to a child named Karl Josef. Four years later, Karl Josef became ill, and he lost much of his capacity for speech and movement. It's no coincidence, Lund believes, that Beethoven entered an unusual period of inactivity and depression, because he was unable to see or help his alleged son or claim him publicly. Lund goes on to claim that Beethoven wrote some of his most religious-themed music — despite being an atheist — as a way of supporting the deeply religious Brentano, communicating with her the only way he could, through his music.

He went deaf at the height of his fame

Contrary to popular misconception, Beethoven was not born deaf. According to Paul Wolf, M.D., a clinical professor of pathology at the University of California, he began to lose his hearing at age 28, and this process was complete by the time he was 44. He likely had Paget's disease, which also resulted in the growth of his head and feet.

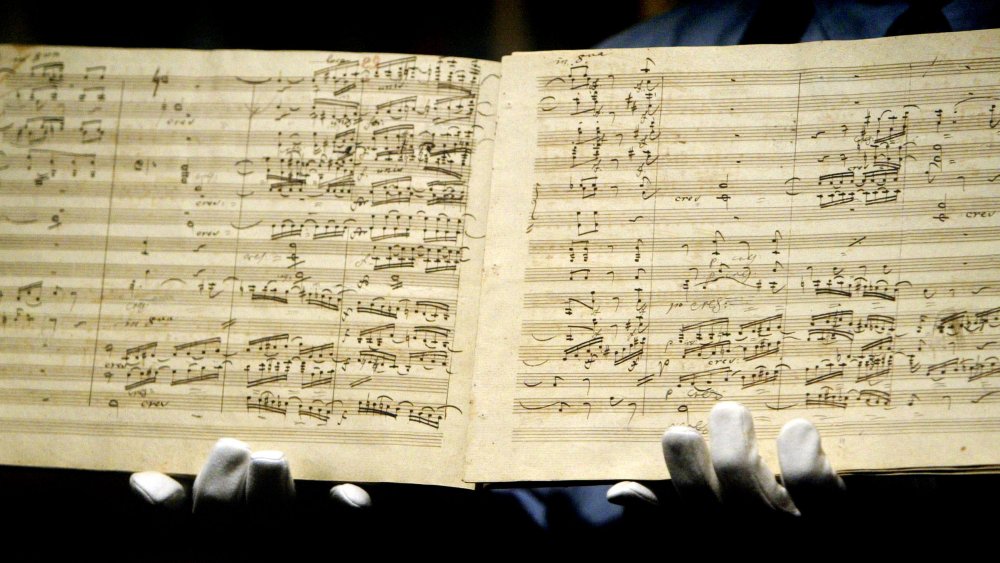

As you might imagine, for a man whose life's work was music, this was devastating. Beethoven struggled against his affliction desperately. Donato Cabrera, music director of the California Symphony, writes that he continued to perform publicly despite eroding results, but when he went totally deaf, he retreated from public life completely. He also lost the ability to hear higher notes first, and so for a time, he would concentrate on playing the lower tones on his instruments because he could still hear them well enough. Cabrera also writes that despite his deafness, Beethoven still knew how music worked, and thus he could still compose. But his work took on a darker, angrier tone in his later years, possibly reflecting the state of mind of someone who'd been given such a tremendous creative gift only to discover it came with an expiration date.

Beethoven contemplated the unthinkable

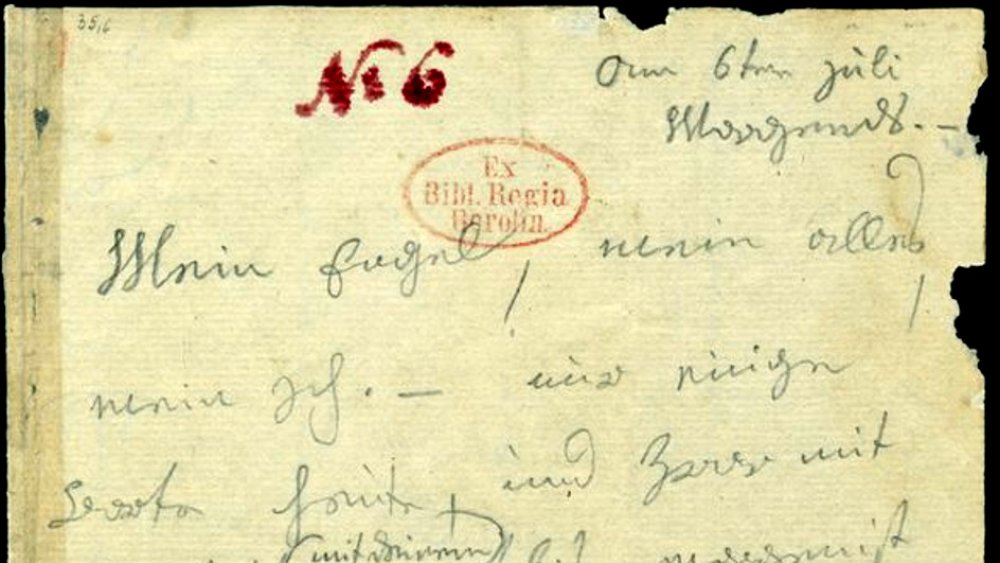

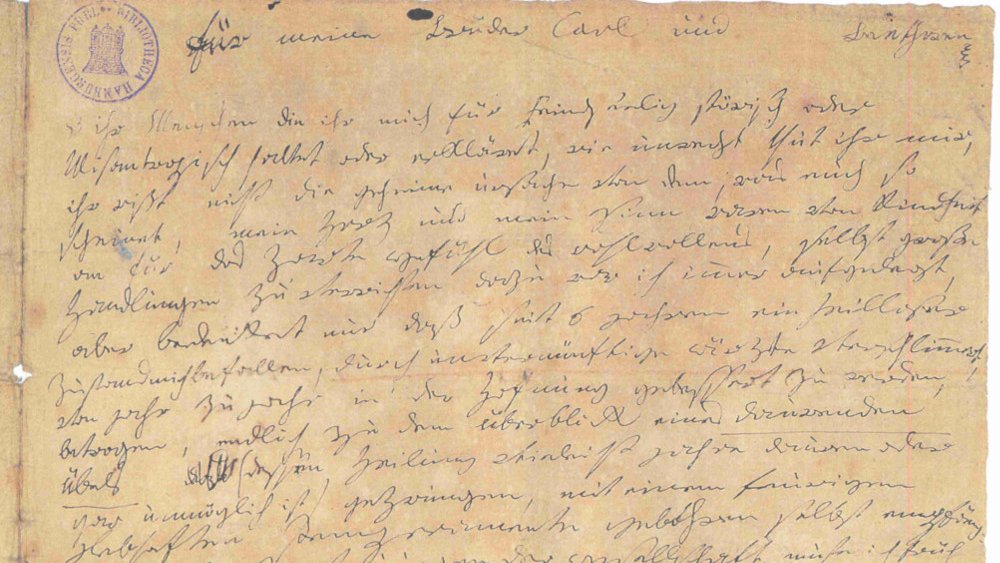

By October 1802, Beethoven, then 32 years old, had been trying to find a cure for his encroaching deafness for several years. Having found nothing that would help, he'd begun to despair. He sat down on October 6 and wrote a letter to his brothers, Kaspar and Johann, that he never sent. It was discovered among his possessions after his death and opened decades later. Journalist Meridee Duddleston writes that the letter, known today as the Heiligenstadt Testament, "depicts his pain and struggle."

It's a raw document that he never sent and perhaps never intended to send, maybe seeing writing the letter as a form of therapy, of working through his emotions and dealing with his pain and frustration. In his growing isolation, he admits to having contemplated suicide, but he closes the letter on a powerfully optimistic note, declaring, "It was Virtue alone which sustained me in my misery; I have to thank her and Art for not having ended my life by suicide." It was a turning point in Beethoven's life, Duddleston notes, and marks a division in musical style and ambition as he headed into what scholars refer to as his Middle Period. Ultimately, the letter is a testament to a man who'd stepped up to the edge of despair but decided to keep going.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

He drove a beloved nephew to despair

Possibly because of the early loss of his mother, his father's cruelty and unreliability, and the fact that he had to take on the role of caring for his younger brothers when still a teenager himself, Beethoven was a bit overbearing as a brother. This was particularly painful when it came to Kaspar, who in 1806 married a woman named Johanna that Beethoven thoroughly disapproved of. The Daily Telegraph notes that the composer considered her to be "immoral." Kaspar originally intended Johanna and Ludwig to share custody of their son, Karl, but Ludwig forced Kaspar to grant him sole custody just two days before Kaspar died. However, Kaspar added a final codicil that granted Johanna joint custody, so Beethoven sued, and even resorted to dirty tricks like pretending the "van" in "van Beethoven" made him a member of the nobility (it didn't) to get an advantage.

Nevertheless, he won custody of Karl in 1820 and was by all accounts incredibly hard on the boy. Karl often ran away to Johanna, and Beethoven once had the authorities track him down and bring him back. Karl rebelled by living the sort of "immoral" lifestyle Beethoven detested, and Beethoven became increasingly harsh, finally driving Karl to attempt suicide in 1826. The attempt failed, but Karl and Beethoven managed to make peace just before Karl joined the army. They never saw each other again.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

He went broke caring for his younger brother

Beethoven spent much of his energy alternately caring for his brothers and meddling in their lives. In 1812, when Kaspar became ill with tuberculosis, historian Jan Swafford writes that "from that point on, a good deal of Ludwig's earnings would go to ... doctors and family support" (which was awkward, because Beethoven and Kaspar's wife, Johanna, hated each other). In fact, historian Barry Cooper estimates that Beethoven spent the equivalent of three years' salary on medical care and other expenses associated with Kaspar's illness, a truly incredible sum for the time that Beethoven funded by taking on personal loans he had little hope of paying back in a timely manner.

The real tragedy, of course, is that owing to the state of medicine at the time, tuberculosis meant certain death eventually. The question wasn't whether Kaspar would die from it, but when he would die. Despite his brother's tireless efforts, Kaspar died in November 1815. After their mother nearly three decades before, this was the second important loved one that the disease had taken from Ludwig, leaving him a little more isolated and lonelier than he'd been.

His own doctors probably poisoned him

We take modern medicine for granted, but we shouldn't. Back in Beethoven's time, your doctor was as likely to kill you as save your life. As Beethoven grew older, a litany of health problems afflicted him. In his final year, he came down with jaundice, with his skin turning yellow, and he suffered a painfully distended abdomen. His doctors drained fluid from the composer by piercing his belly with an instrument.

Interestingly, the LA Times reports that scientists studied Beethoven's hair and bones and concluded that the composer suffered from acute lead poisoning, which might've contributed to his death. Going further, forensic scientist Christian Reiter studied samples of Beethoven's hair in 2007 and discovered that the lead levels in Beethoven's hair spiked directly after each of the procedures with the instrument, and he speculates that Beethoven's doctors might've actually unintentionally killed him via lead poisoning while trying to alleviate his suffering. The levels of lead found in Beethoven might not have killed a healthy person, but years of heavy drinking and other ailments had left Beethoven's liver damaged, and it was unable to handle the influx of poison. Beethoven was suffering from a lot of health issues and might've died soon anyway, but the whole lead poisoning thing certainly didn't help.

Beethoven's final illness was incredibly painful

As The Daily Telegraph observes, by the time Beethoven was in his late 50s, he was deaf and "afflicted by extremely bad breath, chronic, foul body odors, and painful colic from his grossly distended belly." He lay in excruciating pain while his doctors repeatedly pierced his belly to drain fluid. This did little to help, and his suffering was likely incredible towards the end, especially when you consider the long list of problems found at his autopsy.

For example, there was the atrophy of the brain, a fibrotic liver (Beethoven, like his father, was a heavy drinker who reportedly loved to drink fortified wine, and according to physicians Adam K. Kubba and Madeleine Young, he began drinking more in his later years as a way to deal with increasing abdominal pain), an enlarged pancreas, and abnormal kidneys. Later studies revealed elevated lead levels suggesting he was also suffering from lead poisoning — possibly from the instruments his own doctors were using — which likely stressed his liver to the breaking point. For a man who brought so much beauty into the world, his final hours were incredibly unpleasant and painful.