The Tragic True Story Of The Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping

In the early years of flight, a new class of hero was arising, legendary pilots who took the newest flight technologies to their limit and paved the way for all of the aviation advances we saw in the 20th century.

One of those heroes was Charles Lindbergh, an American pilot who flew the first non-stop solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927 in his single engine plane, The Spirit of St. Louis. Overnight, Lindbergh became a household name and an American icon, a name we still remember today.

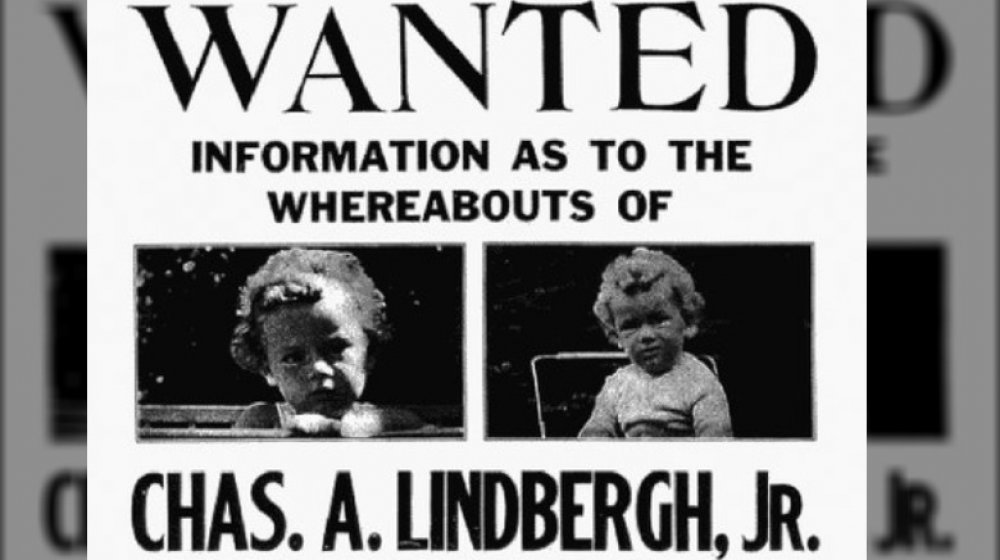

While his later activities were controversial and included some suspicious pro-Nazi leanings and several illegitimate children, he was still considered beyond reproach in the early 1930s, when something terrible happened. Lindbergh's first son, Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr. was kidnapped. The resulting media firestorm swept the nation, and "Baby Lindy" and the mysterious circumstances of his disappearance became a heartbreaking story that shocked America.

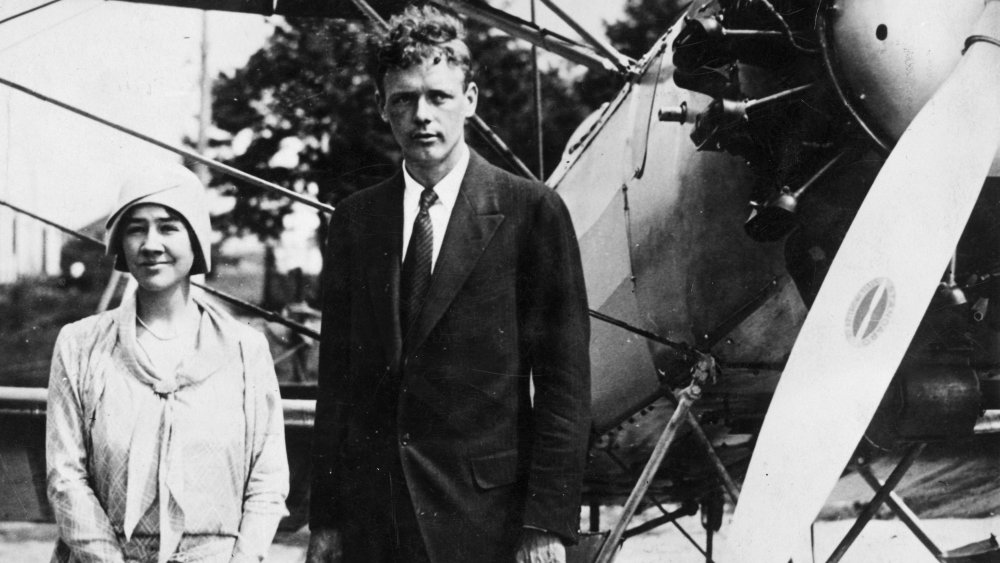

The Lindberghs were young newlyweds

A mere two years after Charles' history-making flight, he married Anne Morrow, who he'd known a very short time. They had only had four dates, but Lindbergh was one of the most eligible bachelors in America and Morrow was the daughter of an ambassador, according to Princeton Magazine. They married on May 27, 1929 and quickly became partners in aviation and exploration. When Anne was seven months pregnant, she broke the transcontinental flight speed record, as if to show she was just as talented a pilot as her husband and could handle anything.

The public were enamored with the Lindberghs, and newspapers reported on their every move, an early example of paparazzi-style celebrity coverage. When their son, Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr. was born, the American people celebrated. The Lindberghs and their whirlwind romance were depicted as an American fairy tale love story. The press couldn't stop printing stories about Charles and Anne, and the people couldn't stop reading them.

Charles Jr. was born in June of 1930, a little over a year after the Lindberghs' wedding. Just like his famous parents, "Baby Lindy," as he came to be called, was beloved by the public. And so the people were shocked when newspapers announced the young Lindbergh had been kidnapped on March 1, 1932 — just a few months shy of his second birthday.

Baby Lindbergh was kidnapped from his own room

The Lindberghs were at home in East Amwell, NJ when the baby's nurse came to Anne Lindbergh, asking if she had her son with her. Anne had just been in the bath and didn't have him. It was 10 P.M., full dark outside. The nurse then went to inform Charles Lindbergh she couldn't find the baby, according to Crime Museum.

Upon investigating the child's room, they found him missing and a small envelope near the windowsill. It had a ransom note inside. The Lindberghs immediately called the police and their lawyer. Investigators found the remains of a hand-built wooden ladder leading directly up to the child's second story window. The kidnapper had struck while the Lindberghs were at home, taking the child from his own nursery. By morning, news of the boy's kidnapping was everywhere.

While this brought a lot of attention to the case and thus, more people looking for Baby Lindy or anything suspicious in general, it also meant the Lindberghs suddenly had an influx of people offering their help. The New Jersey state police took over jurisdiction of the case, and the police supervisor, Col. Norman Schwarzkopf (father of the military general of the same name), let Charles Lindbergh himself head up the investigation of his own son's kidnapping. This was unusual, even back then, but Lindbergh had a lot of money and connections, which probably helped him convince the police to let him onboard.

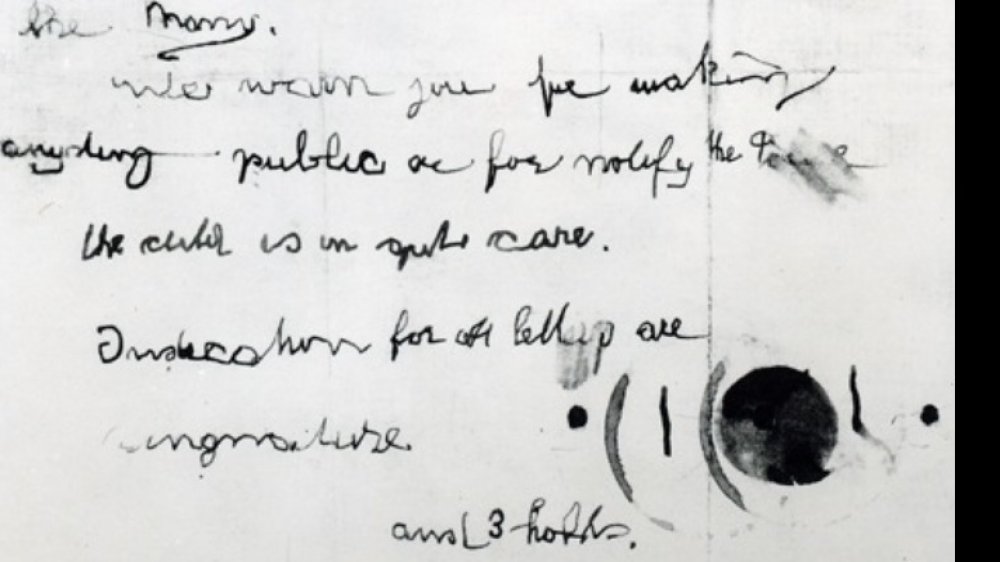

The ransom letter was very weird

The only solid pieces of evidence the police had were the ransom letter and the makeshift ladder. The ladder was broken, and investigators assumed it failed when the kidnapper tried to scale back down it. While it seemed of only mild interest at the time, the ladder would later figure heavily in a criminal trial related to the case.

The ransom letter included some unusual writing choices, as archived by the FBI. For example, the amount of the ransom (initially $50,000) had the dollar sign after the amount, something typically not seen in English. This led investigators to conclude the writer was not a native English speaker. Later in the note, the phrase "the child is in gut care" appeared. This seemed to indicate the writer was possibly German, as "gut" is German for good. The kidnapper sent several more ransom notes later with similar oddities and misspellings, such as "boad" instead of "boat" — something else that would later come up in court.

Strangest of all was the note's "signature." It wasn't a typical signature, but instead was an eerie symbol made up of interlocking circles colored blue and red, along with three holes punched directly in the paper, according to PBS. The ransom note said this symbol would indicate future letters from the kidnapper, and indeed, future ones did have it, holes in the paper and all.

Charles Lindbergh initially suspected mob involvement

While clues were scarce at the beginning of the investigation, suspicion landed on the mob being the potential kidnappers. Lindbergh reached out to two bootleggers he knew and, through their contacts, tried to probe the criminal underworld of New York and New Jersey to see if anyone knew anything about his son's disappearance, according to Famous Trials.

Surprisingly, the mob was fairly cooperative. While they apparently didn't have any useful information (at least, not any that was ever made public), they were on Lindbergh's side, and even infamous gangster Al "Scarface" Capone himself offered up a $10,000 reward for anyone with information regarding the whereabouts of Baby Lindy.

Of course, Capone wasn't being completely altruistic, according to the Library of Congress. Part of the deal was also that he be released from prison to be the most help. He was just a few months into a jail stay that would eventually turn into a full prison sentence for tax evasion. This actually led many people, including U.S. Senators, to speculate Capone had arranged for the kidnapping specifically to try this very scheme. Capone made several more offers, but was denied each time. Whether or not he and his numerous associates would have really been able to help or if it was simply an attempt to get a "get out of jail free" card is unknown, and eventually, Capone and the mob were found to have no involvement in the kidnapping.

The intermediary was a stranger to the Lindberghs

Much like Al Capone, a great many people offered their assistance with the Lindbergh kidnapping. One of these was a man in his 70s by the name of Dr. John Condon. He placed an ad in the newspaper offering $1,000 of his own money to the kidnapper to act as a go-between for them and the Lindberghs. It's not clear exactly why he made this offer or why he decided to take it upon himself to do this, but amazingly, the kidnapper responded the following day by sending a letter directly to Condon, according to Famous Trials.

The letter said the kidnapper agreed to make Condon their liaison, and asked him to contact Lindbergh about obtaining their ransom money. The letter included the strange symbol seen on the original ransom note, verifying the letter did come from the kidnapper. Condon reached out to Lindbergh about this new letter, and remarkably, Lindbergh not only accepted as well, but even worked directly with Condon, showing him items belonging to his son so Condon might identify him if necessary.

Condon and the kidnapper then began an elaborate communication using classified ads in the newspaper. Condon used the pseudonym "Jafsie", inspired by his own initials, John F. Condon, or JFC. The kidnapper, in turn, would hire taxi drivers to deliver letters directly to Condon in reply.

The kidnapper asked for a higher ransom

While the initial ransom note left in the baby's nursery asked for $50,000, the kidnapper apparently changed their minds later on and decided to ask for an additional $20,000, for a total of $70,000 for the safe return of Charles Jr. While that may already sound like quite a lot to most people even today, keep in mind, this was the early 1930s, in the middle of the Great Depression. According to a 2014 article in National Geographic, the initial $50,000 would have been approximately $850,000 in 2014 dollars.

The full $70,000, however, would have been much more. In 2020 dollars, that would be a ransom of over $1.2 million. Of course, there are kidnappings out there that have asked for much higher ransoms, but this was pretty early days for what we think of as a typical kidnapping today. As strange as it sounds, the Lindbergh kidnapping was fairly groundbreaking in terms of what criminals and investigators expect nowadays.

Since it was an extremely high profile kidnapping, and Lindbergh had made quite a fortune since he made his famous flight, the kidnapper apparently felt comfortable asking for a larger ransom. Having no other choice, the Lindberghs, Condon, and the police continued to cooperate and negotiate with the kidnapper.

Dr. Condon met the kidnapper in a cemetery

On March 12, 1932, the doorbell rang at Dr. Condon's house. Upon answering it, he received another note from someone hired by the kidnapper. It asked him to go to an empty local hot dog stand, where he'd find another note under a rock. He found it, and it instructed him to meet in the cemetery across the street. After entering the cemetery, Condon saw a man with a handkerchief over his face, gesturing at him. He spoke to the man briefly, but a passerby spooked the stranger and he ran.

Amazingly for a man in his seventies, Condon chased down the man, then sat with him on a bench to talk. The man had a German accent, according to Famous Trials. He called himself John, and was later dubbed "Cemetery John" by the press, which would be an awesome nickname if it wasn't tied to a terrible crime.

Cemetery John offhandedly asked Condon, "What if the baby is dead? Would I burn if the baby is dead?" Condon was alarmed, but Cemetery John reassured him the baby was alive, and he'd send the boy's pajamas as proof. He also mentioned a mysterious person he called "Number One," thus implying the kidnapping had involved multiple parties. After this, Cemetery John departed, and the baby's sleep outfit he had been wearing the night of the kidnapping was delivered to Condon and the Lindberghs a few days later.

The Lindberghs couldn't secure $70,000

A few weeks later, on March 30, 1932, Condon received another letter from the kidnapper. They were impatient and told Condon and the Lindberghs to have the money ready in the next four days. With the help of the Internal Revenue Service, they managed to get $50,000 together, the original ransom amount. They were $20,000 short of the revised ransom amount of $70,000, but agreed to meet with the kidnapper anyway, according to Crime Museum.

For the second time, the kidnapper asked to meet in a cemetery, separate from the one where they had previously met Dr. Condon. On April 2, 1932, Condon once again met with Cemetery John, who accepted the ransom that was $20,000 short. After handing over the money, instead of returning the child, Cemetery John instead gave Condon yet another note. This one claimed the child was safe, on board a boat named Nelly off the coast of Massachusetts.

Condon brought the note to Charles Lindbergh, who was familiar with the area the note described, but didn't set out until morning for better visibility. He flew over the area specified for hours, looking for the boat, but found nothing, according to Famous Trials. The kidnapper had lied, there was no such boat. After this, the Lindberghs and Dr. Condon didn't hear from the kidnapper again. The case went cold for over a month.

A truck driver made a grim discovery

The Nelly was never located after multiple searches, the kidnapper had stopped sending notes, and the Lindberghs were out $50,000, not a small sum. It seemed like things couldn't get any worse, but then they did. Six weeks later, on May 12, 1932, a truck driver named William Allen stopped by the side of the road near some woods to answer the call of nature. It was then he saw a small body poking out of the ground, according to Famous Trials. Allen contacted police.

They investigated and confirmed it was the body of Charles Jr., buried in a shallow grave less than a mile from the Lindbergh house. Worse still, he had been dead since the night of his kidnapping, according to History. The kidnapper never had any intention of returning the baby because they knew he could not be returned, and Cemetery John asking Condon if he'd burn if the baby was dead suddenly made much more sense.

Medical examiners determined the child had died from blunt force trauma to the head. They concluded he had likely been dropped when the ladder split as the kidnapper exited the Lindbergh house. Devastated, Charles and Anne Lindbergh sold the house not long after and moved far away from the place that now contained so many horrible memories. The media and the public were shocked and heartbroken by the news.

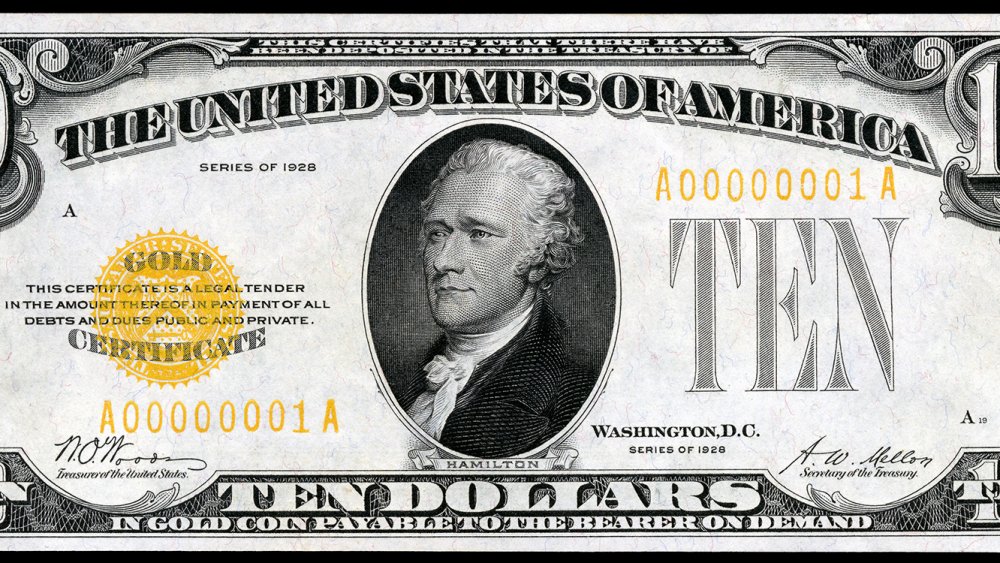

The kidnapper seemed to make a mistake

Police had nothing to go on. After the discovery of Baby Lindy's remains, the trail was lost. The kidnapper had seemingly vanished. The IRS did have one possible foothold: They had copied the serial numbers of the ransom money, including gold certificates (pictured), which were more uncommon than regular cash as they were being phased out. Unfortunately, they didn't have a way to flag serial numbers back then. It would require manually checking the numbers.

It wasn't until two and a half years later, in fall of 1934, this finally paid off, according to Famous Trials. A teller at Corn Exchange Bank in the Bronx came across a gold note with a license plate number written in the margin. Feeling this was suspicious, the teller contacted the police. They traced the bill back to a gas station. The owner there had copied down the license plate of the man who gave him the note because he said something odd during the transaction. When the owner remarked he didn't see many gold notes anymore, the man replied, "No, I only have about 100 left."

Using the license plate number, police arrested a German carpenter named Bruno Hauptmann. Investigating his home, they found $15,000 with serial numbers matching the ransom money, Dr. Condon's phone number written on a wall, and a missing board in the attic that matched the makeshift ladder found outside the Lindberghs' house.

The trial of the century

Hauptmann's trial was a media circus unlike anything before it. Readers hung on every word reporters wrote, and the whole affair was dubbed the "Trial of the Century." Hauptmann claimed innocence. His alibi for the most damning evidence, the ransom bills, was that the money had been left to him by an acquaintance named Isidor Fisch. A fellow German, Fisch had purportedly asked Hauptmann to safeguard some belongings for him while he visited Germany. Fisch died of tuberculosis shortly after arriving in Germany, though, and once Hauptmann found out Fisch was dead, he decided to see what was in the boxes Fisch had left, according to Famous Trials.

Inside, he claimed to have found the ransom money. Since Fisch was dead, Hauptmann helped himself to the cash and began spending it. Investigators confirmed Fisch was a real person, he had been friends with Hauptmann, and he had died in Germany. While this introduced doubt to a key component of the prosecution's case, they went ahead using experts in handwriting analysis, wood identification, and dozens of witnesses, including both Lindberghs and Dr. Condon. They even presented a journal of Hauptmann's where he had misspelled "boat" as "boad," similar to the ransom notes.

Hauptmann was convicted and sentenced to death. He maintained his innocence, even amidst offers to avoid execution if he confessed. On April 3, 1936, just over four years after the death of Charles Jr., Hauptmann was executed in the electric chair.

Questions remained about the the Lindbergh baby kidnapping case

Now, nearly 100 years later, alternative theories about the case continue to perpetuate. Most common of these is that Hauptmann was innocent, and police tampered with evidence and produced false testimony to railroad Hauptmann and end the case. Hauptmann's arrest and execution, they say, was a big frame job, enabled by the fact that the case was so enormously high profile and the public was desperate to see someone put away for the horrible crime.

One of these people was Hauptmann's own wife, Anna. After documents regarding the case were publicly released in the 1980s, Anna Hauptmann sued the state of New Jersey, accusing them of framing her husband. The case was thrown out for being far past the statute of limitations and because the judge found no compelling evidence the case was mishandled. Hauptmann and her lawyers appealed this all the way to the Supreme Court more than once, but ended up being denied each time, according to the L.A. Times.

While plenty of doubt has been raised about nearly every single piece of evidence in the case, to date there's no proof Hauptmann was convicted unjustly, according to Jim Fisher, a crime writer, former FBI agent, and professor of criminal justice at Edinboro State College. But in a case with no eyewitnesses to the crime and no confession, plenty of room for doubt remains.